Open reduction with or without internal fixation

1. Emergency treatment

Emergency treatment in orbital fractures is always indicated in the following situations:

- Partial or complete visual loss due to direct or indirect optic nerve trauma

- Severely increased intraocular pressure

- Acute space-occupying lesion creating increased intraorbital pressure (eg, retrobulbar hematoma, orbital emphysema)

- A severe shift of orbital content

- Severe entrapment of eye muscle (particularly in pediatric patients, “trapdoor”)

Globe rupture and intraocular trauma

These injuries require ophthalmological intervention.

Retrobulbar hematoma

A pressure increase in the periorbital region due to a retrobulbar hematoma can cause significant injury such as the creation of compartment syndrome with injury of the neurovascular structures and the possibility of vision loss.

Read more details about retrobulbar hemorrhage here.

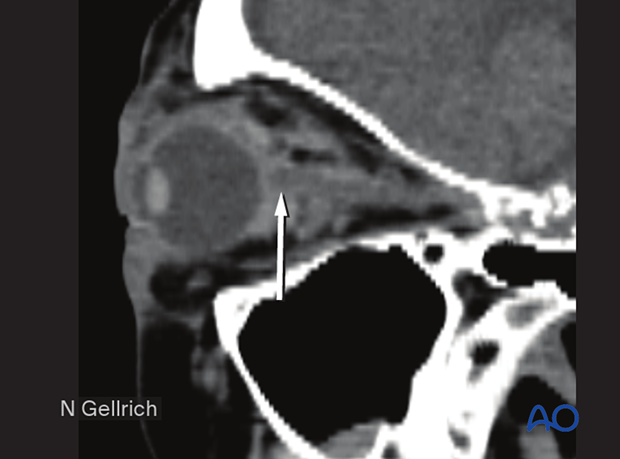

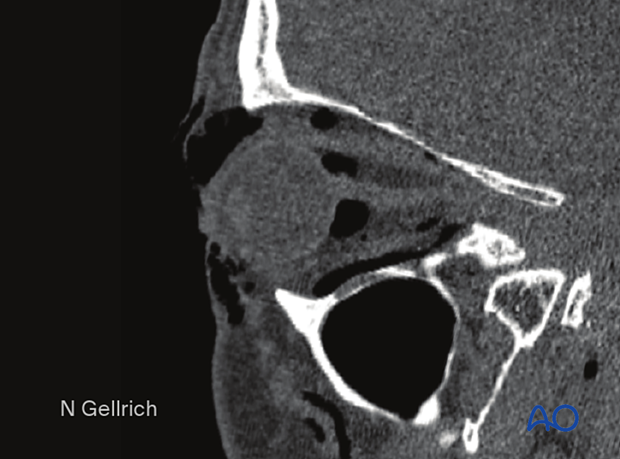

This CT scan sagittal view shows a small retrobulbar hematoma.

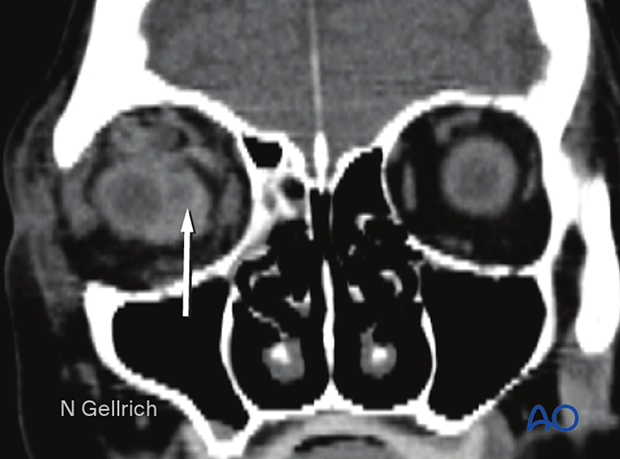

Coronal view of the same retrobulbar hematoma.

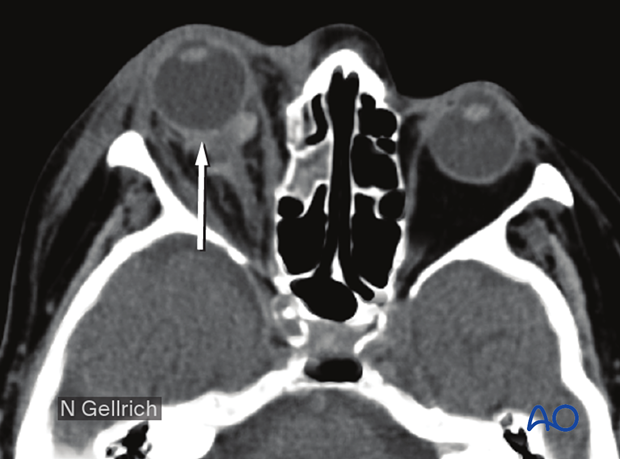

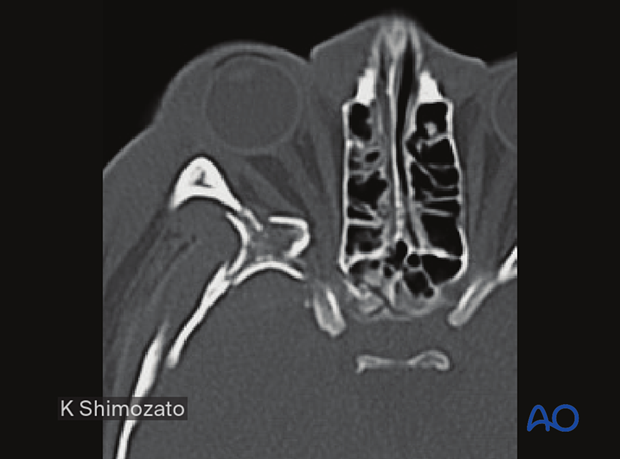

Axial view of the same retrobulbar hematoma.

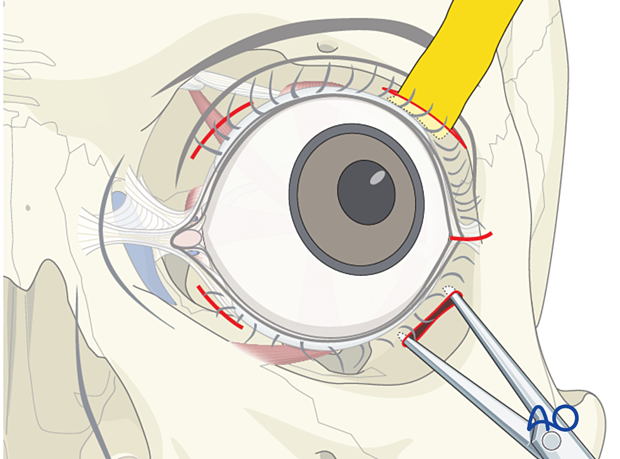

If a retrobulbar hematoma leads to a tense, proptotic globe with acute visual disturbances, emergency decompression should be initiated. This situation requires urgent decompression, such as cantholysis, removal of implanted reconstructive material, and/or evacuation of a loculated hematoma under general or local anesthesia.

Transcutaneous transseptal incisions help evacuate the hematoma and relieve excess periorbital pressure. Alternative methods such as transconjunctival pressure release, lateral canthotomy, and inferior cantholysis may also be considered according to patient condition.

An exception may be pulsatile exophthalmos which can be a sign of a carotid-cavernous sinus fistula. A fistula of this nature requires appropriate preoperative imaging and planning.

Emphysema

Severe emphysema might significantly raise intraorbital pressure. If this compromises visual function or endangers the orbital contents, orbital decompression must be considered.

Patients with signs of intraorbital emphysema are given antibiotics and decongestive nasal drops.

To avoid additional emphysema due to acute pressure rise, patients with sinus fractures in the periorbital region should not blow their nose. They should also be instructed to sneeze with an open mouth to minimize the increase of intranasal/intrasinus pressure.

Usually, there is no need for emergency treatment of orbital floor/medial wall fractures unless there is severe ongoing hemorrhage in the orbital cavity, the paranasal sinuses, the nasal cavity, or fractures which create muscle ischemia.

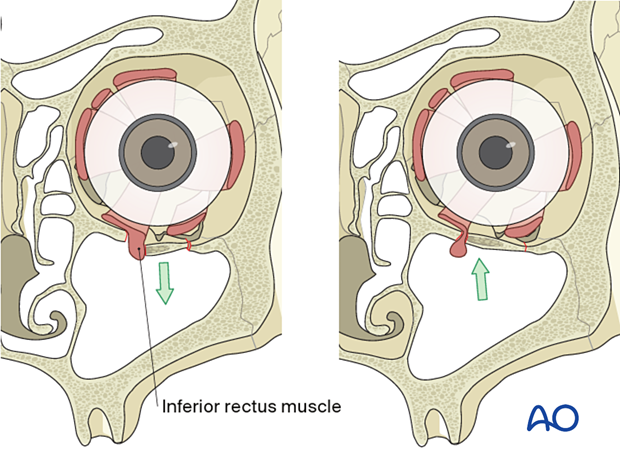

In younger patients there is a danger of necrosis of the entrapped rectus muscle due to the so-called “trapdoor” phenomenon. In such cases, immediate release of entrapped tissues is necessary.

More information on the trapdoor phenomenon can be found in the orbital reconstruction treatment for orbital floor fractures in the Surgery Reference pediatric trauma section.

Bone fragments affecting the optic nerve

Special attention should be given to the posterior third of the orbit, the superior orbital fissure, and the optic canal. Fractures and hematoma formation in these anatomical areas can be associated with superior orbital fissure syndrome and optic nerve injury.

In this image the axial CT scan in the plane of the optic nerve shows multiple fractures of the lateral orbital wall and the greater wing of the sphenoid of the right side. Compression or displacement (stretching) of the optic nerve may be produced.

Displaced fracture fragments in the posterior third of the orbit may create nerve compression.

Severe bleeding

In case of severe nasal, oral, or pharyngeal hemorrhage, the following options should be considered:

- Assessment of current medical treatment for anticoagulation such as Coumadin, aspirin, or other antiplatelet medication

- Compression, either by nasal packing, balloon tamponade, or direct compression

- Electrocautery or ligation if a clear bleeding source can be identified

- Normalization of blood pressure

- Interventional radiologic embolization if simpler methods fail

- In some cases, reduction of fracture displacement may significantly reduce bleeding

2. Selection of approach

The orbital floor can be reached by various lower eyelid approaches (transcutaneous, transconjunctival, or existing lacerations). The type of incision must suit the requirements of fracture reduction and reconstruction, surgeon skill, and the patient.

Less frequently used is a transoral/transnasal maxillary sinus approach to reach the orbital floor from below. The maxillary approach does not provide visualization of the contour of the orbit.

Care should be taken not to damage the following:

- Palpebral anatomical structures

- Lacrimal drainage systems

- Ocular muscles

- Neural structures

Additional information about orbital anatomy and dissection can be found in the links below:

- Preoperative considerations

- Anatomy of the bony orbit

- Correlation of surface and cross-sectional anatomy

- Introduction to periorbital dissection

- Orbital floor dissection

- Medial orbital wall dissection

- Lateral orbital wall dissection

- Orbital roof dissection

- Adjunctive access procedures (orbitotomies)

- Retrobulbar hemorrhage

3. Reduction with or without fixation

Reduction without fixation

Upon reduction the orbital floor may appear stable without fixation. Fixation in these cases may not be necessary, but a close follow-up should be conducted.

Reduction with fixation

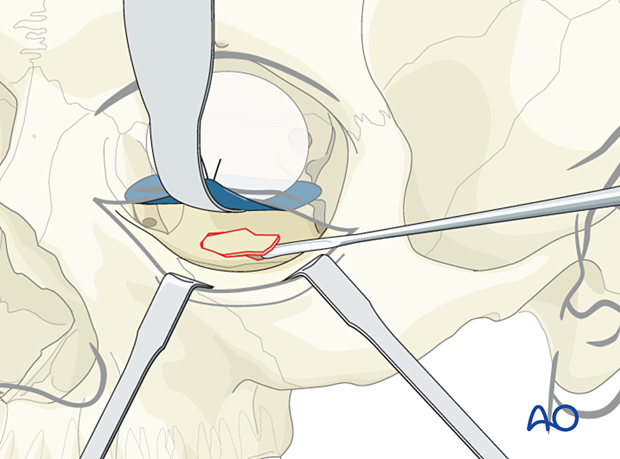

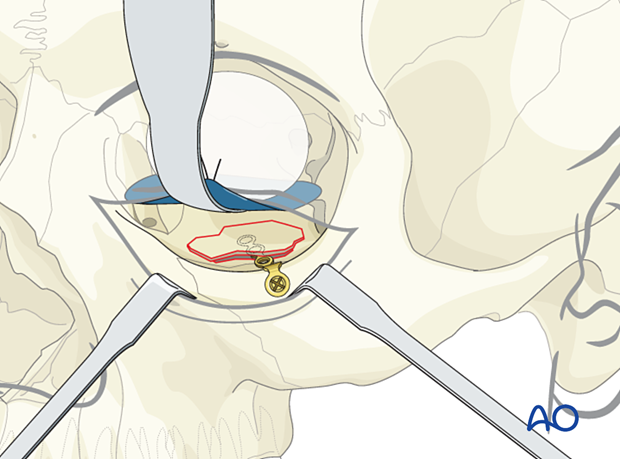

In some cases, the orbital floor may be reduced, but the fragment is not stable. A small bone plate can then be secured to the stable bone laterally within the orbit, and the medial extension placed under the reduced bony fragment.

Another option is to remove the bone fragment and reconstruct the defect with alloplastic material.

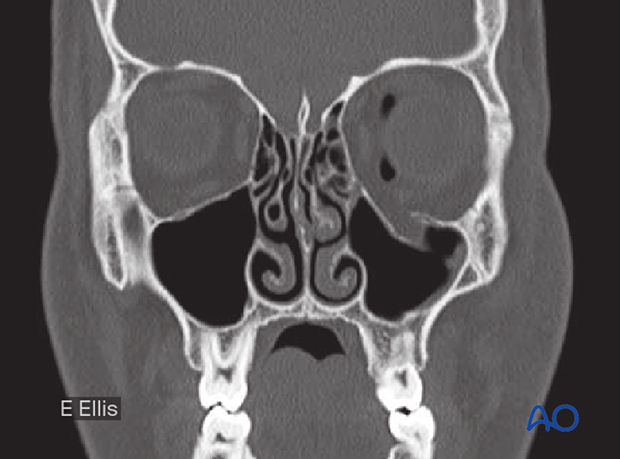

The image shows a preoperative coronal CT scan.

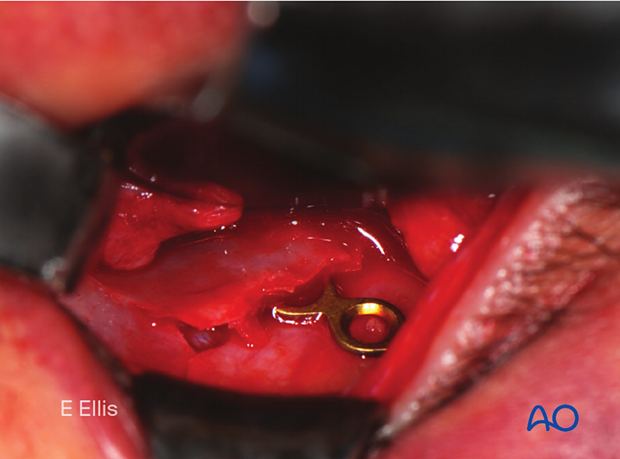

An intraoperative photograph of the same patient with a fixation plate supporting the reduced bone fragment.

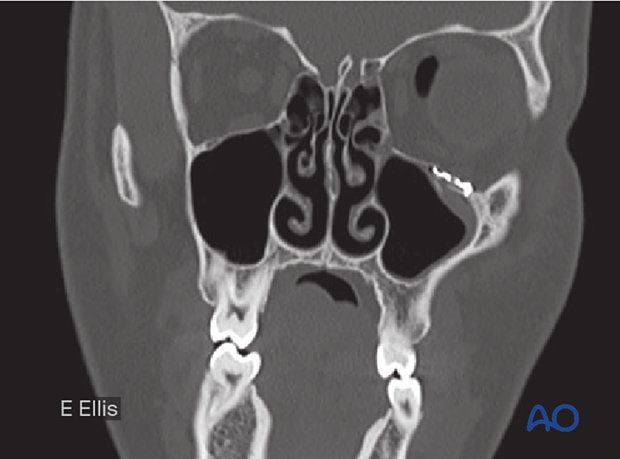

A postoperative coronal CT scan of the same patient.

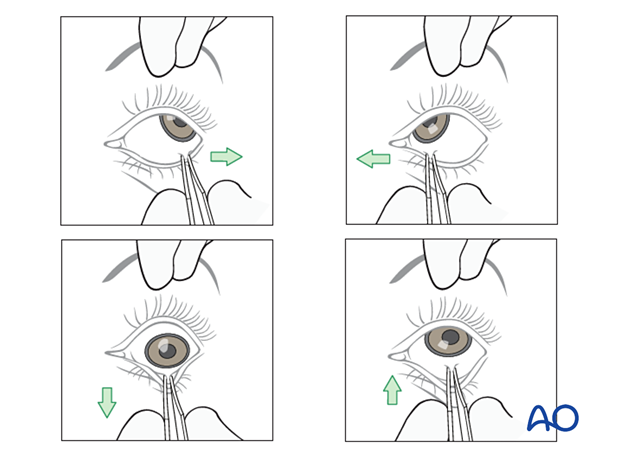

Forced duction test

After the insertion of an implant and before closure, it is imperative to perform a forced duction test and to examine the state of the pupil.

4. Aftercare

Evaluation of the patient’s vision

Patient vision is evaluated on awakening from anesthesia and then at regular intervals until hospital discharge.

A swinging flashlight test may serve to confirm pupillary response to light in the unconscious or non-cooperative patient; alternatively, an electrophysiological examination must be performed but this is dependent on the appropriate equipment (VEP).

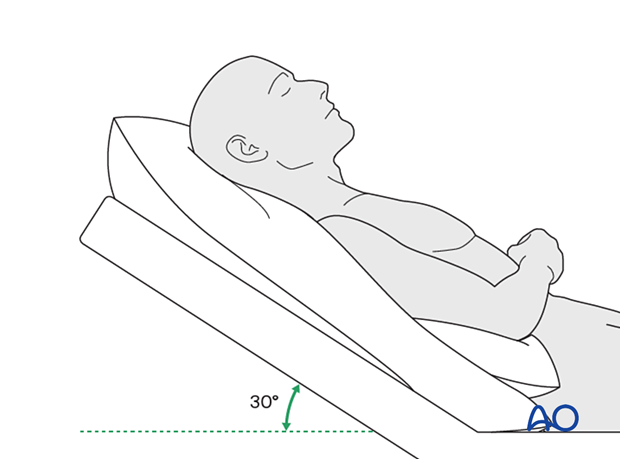

Postoperative positioning

Keeping the patient’s head in a raised position both preoperatively and postoperatively may significantly reduce edema and pain.

Nose blowing

Nose blowing should be avoided for at least ten days following fracture repair to prevent orbital emphysema.

Medication

The use of the following perioperative medication is controversial. There is little evidence to make solid recommendations for postoperative care.

- No aspirin for seven days (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use is controversial)

- Analgesia as necessary

- Antibiotics: many surgeons use perioperative antibiotics. There is no clear advantage of any antibiotic, and the recommended duration of treatment is debatable.

- A nasal decongestant may be helpful for symptomatic improvement in some patients.

- Steroids, in cases of severe orbital trauma, may help with postoperative edema. Some surgeons have noted increased complications with perioperative steroids.

- Ophthalmic ointment should follow local and approved protocol. This is not generally required in the case of periorbital edema. Some surgeons prefer it. Some ointments have been found to cause significant conjunctival irritation.

Ophthalmological examination

Postoperative examination by an ophthalmologist may be requested. The following signs and symptoms are usually evaluated:

- Vision

- Extraocular motion (motility)

- Diplopia

- Globe position

- Visual field test

- Lid position

- If the patient complains of epiphora (tear overflow), the lacrimal duct must be checked

- If the patient complains of eye pain, evaluate for corneal abrasion

Postoperative imaging

Postoperative imaging must be performed within the first days after surgery. 3D imaging (CT, cone beam) is recommended to assess complex fracture reductions. An exception may be made for centers capable of intraoperative imaging.

Wound care

Ice packs are effective in the short term to minimize edema.

Remove the sutures from the skin after approximately five days if non-resorbable sutures have been used.

Avoid sun exposure and tanning to skin incisions for several months.

Diet

Diet depends on the fracture pattern.

A soft diet can be taken as tolerated until adequate healing of the maxillary vestibular incision.

Clinical follow-up

Clinical follow-up depends on the complexity of the surgery and whether the patient has any postoperative problems.

With patients that have fracture patterns that include periorbital trauma, issues to consider are the following:

- Globe position

- Double vision

- Other vision problems

Other issues to consider are:

- Facial deformity (including asymmetry)

- Sensory nerve compromise

- Problems of scar formation

Eye movement exercises

Following orbital fractures, eye movement exercises should be considered.

Implant removal

Generally, implant removal is not necessary except in the event of infection or exposure.

Follow-up

The patient needs to be examined and reassessed regularly. Follow-up imaging at 3–6 months is helpful to ensure proper pneumatization of the sinuses (particularly, mucocele formation must be ruled out), sealing of the skull base, and stability of fragment position.

Special considerations for orbital fractures

Travel in commercial airlines is permitted following orbital fractures. Commercial airlines pressurize their cabins.

Facial fractures may predispose to Eustachian tube dysfunction due to pharyngeal swelling. Forced air insufflation by holding the nose, closing the mouth and attempting expiration and the use of decongestants can relieve middle ear pressure and drum discomfort.

Mild pain on ascent or descent in airline travel may be noticed. Flying in unpressurized aircraft, such as military planes, should be avoided for a minimum of six weeks.

No scuba diving should be permitted for at least six weeks.