Open reduction internal fixation

1. Principles

General considerations

Surgical airwayConsiderations related to establishing proper dental occlusion require a nasotracheal intubation. Alternatively, a submental/submandibular intubation could be considered. Other possibilities include placement of the endotracheal tube through a gap in the dentition or behind the posterior molars.

Depending on the patient’s general condition, a tracheostomy might also be considered and is the first choice where brain or pulmonary injuries are likely to require prolonged intubation.

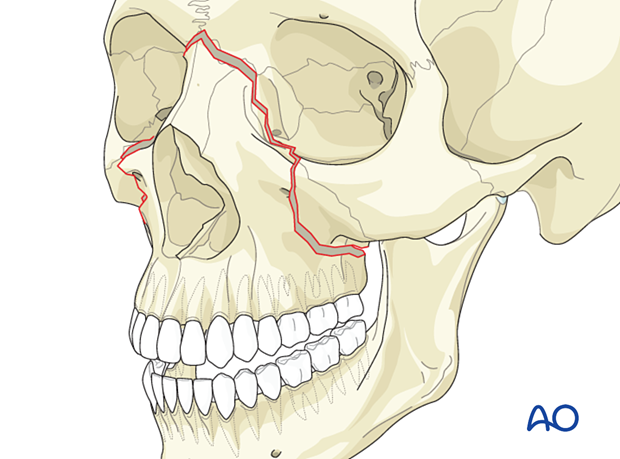

Successful reconstruction of midface fractures aims to reestablish the continuity and position of midfacial vertical buttresses. These pillars even serve a critical role in patients who lack dentition (partial or completely edentulous).

A fundamental principle in Le Fort fracture treatment is to reestablish the premorbid dental occlusion. Portions of the pterygoid plates and associated musculature are still attached to the posterior portion of the maxilla, so passive mobilization of the fracture can be difficult in incomplete or impacted fractures.

To properly achieve a passive maxillary position, the fracture must be completed and the maxilla able to be passively repositioned. An osteotomy is required or strong mobilization forces used to complete the fracture. Rowe’s disimpaction forceps, a “Stromeyer” hook, Tessier retromaxillary mobilizers, etc, can be utilized for this purpose.

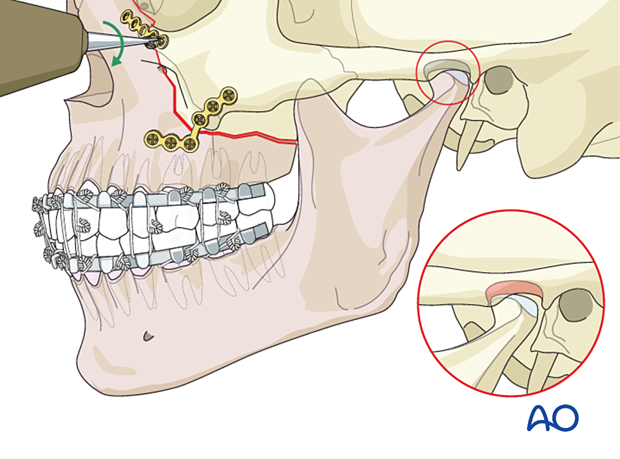

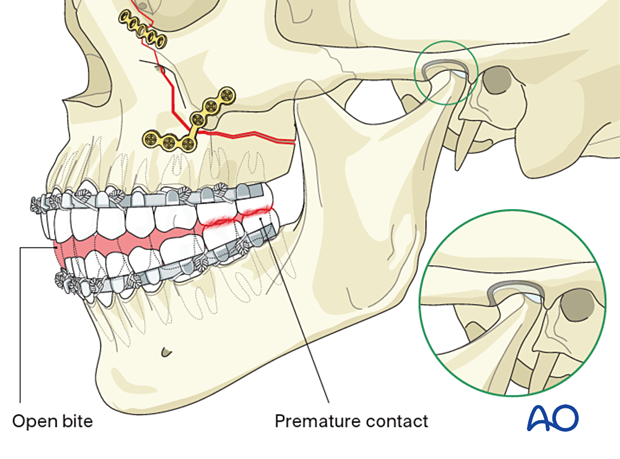

The goal is to achieve correct anatomical repositioning, which may be confirmed by dental occlusion when MMF is released. It is possible to displace the mandibular condyles from the glenoid fossae during the application of MMF. When the MMF is released, the condyles re-seat into their normal position in the glenoid fossae, resulting in a malocclusion.

Other methods to confirm proper reduction include intraoperative imaging and 2D or 3D CT evaluation. If available, dental casts, stereolithographic models, dental records, or premorbid photographs may also be helpful guides for treatment planning.

As a general principle, all facial fractures should be exposed and reduced before plating.

Choice of implant

It is difficult to have absolute guidelines as to the strength of the plates that would be used at the three key points of fixation for a Le Fort II fracture:

- The plate placed for the fixation of the fracture at the zygomaticomaxillary buttress is generally a larger plate. The highest forces of mastication are in this area. Depending on the fracture pattern, an L-plate or a straight plate can be considered.

- If a plate is used along the infraorbital rim, it must be a low-profile plate. The forces in this area are small, and patients may complain of palpating the implant if a larger plate is placed.

- If a plate is used at the nasofrontal area, several options are possible, including one or two straight plates or various Y or X plate configurations. Sometimes inter-fragmentary wires provide sufficient alignment and are not palpable. In many cases the zygomaticofrontal suture can be aligned with an inter-fragmentary wire and provides adequate fixation when one or both of the other two sites of the zygoma are stabilized with plate placement.

Other factors affecting the size and strength of the plate are:

- Grade of instability and comminution of the fracture

- Association with other midface fractures

- The decision to temporarily keep the patient in MMF postoperatively

Click here for a description of implant options.

Orbital involvement

A Le Fort II fracture involves a fracture of the orbital floor and possibly the medial orbital wall. If significant, these fractures are treated in the same way as other orbital fractures in this location. An orbital wall reconstruction with bone graft or alloplastic material may be required. Click here for further details on the reconstruction of combined medial wall and orbital floor fractures.

Teaching video

AO Teaching video on fixation of a complex midface fracture

2. Approaches

The following approaches are relevant for this procedure:

- Approaches to the maxilla

- Lower eyelid - transcutaneous approaches

- Lower eyelid - transconjunctival approaches

- Glabellar approach

- Coronal approach

- The use of existing lacerations

The direct ethmoidal approach (Lynch) is generally not recommended

3. Reduction

Arch bars

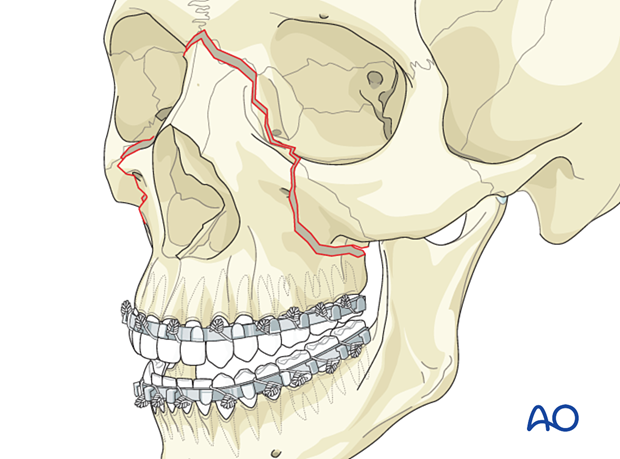

First, arch bars are secured to the dentition. Click here for a detailed description of maxillomandibular fixation.

Option: hybrid arch bars

You can choose between traditional arch bars or hybrid arch bars.

Hybrid arch bars use screws to fix the arch bar to the bone, making the procedure faster.

Mobilization

After exposure of the fracture segments through a maxillary vestibular approach, the fracture is mobilized to enable reduction and fixation. In cases where the maxilla mobilization cannot be accomplished using conventional methods, additional osteotomies may be required. Many surgeons prefer completing a Le Fort I level osteotomy resulting in free positioning of the Le Fort I segment rather than creating additional fractures at the Le Fort II or III levels using a device such as Rowe forceps for forced manipulation.

Reduction instruments

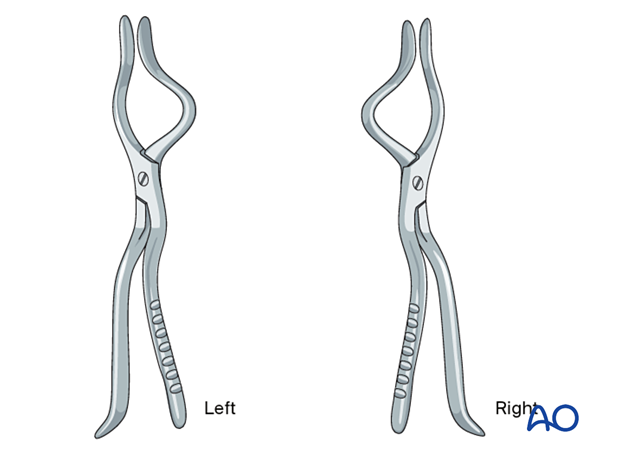

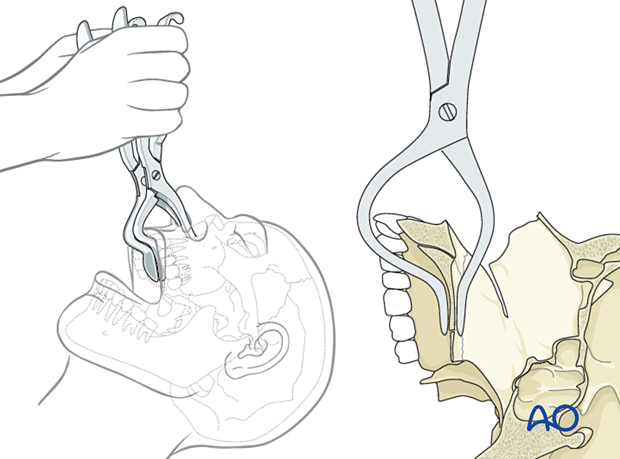

Rowe disimpaction forcepsThe Rowe disimpaction forceps are side-specific. They allow the application of significant amounts of force to disimpact and reposition the maxilla and midface.

It should be noted that in cases of incomplete fracture many surgeons prefer to complete the fracture at the Le Fort I osteotomy level as a safer maneuver than using Rowe forceps for forced disimpaction.

If Rowe forceps are utilized, special attention must be paid to the correct placement of the forceps so that the upper anterior dentition is not harmed.

The maxillary fracture must be completely mobilized to allow for free repositioning.

According to regional preferences and various schools of teaching, different bone hooks may be used for fracture mobilization and reduction. In general, they are all inferior to completion of the fracture with a Le Fort I osteotomy.

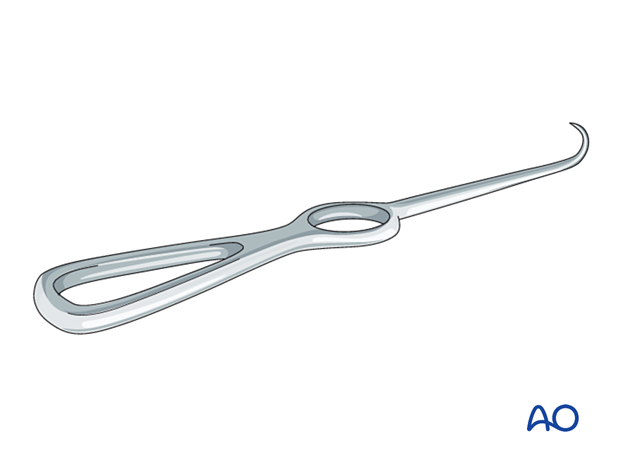

The Stromeyer hook is very versatile for the transoral reduction of Le Fort fractures.

In selected cases, the Stromeyer hook can also be used to manipulate the Le Fort complex by hooking the tip of the instrument inside the piriform aperture and pulling it downwards and forwards. This technique is sometimes referred to as the “downfracture procedure” in Le Fort osteotomies.

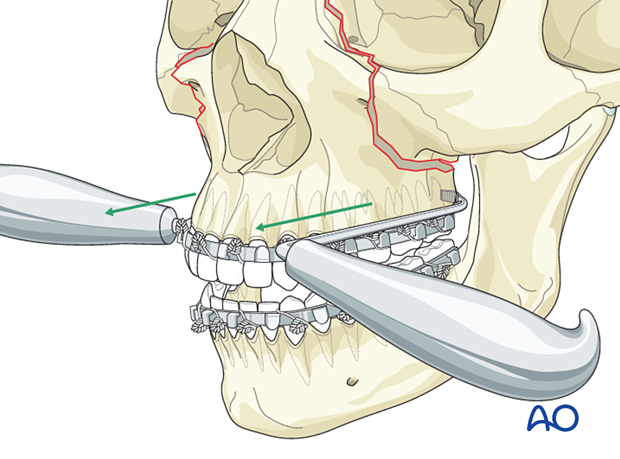

The Tessier retromaxillary mobilizers are placed behind the maxillary tuberosities to help mobilize a posteriorly displaced and impacted maxilla, facilitating passive repositioning and a normal occlusion. The repositioned maxilla must be passive to ensure that it remains in the correct position.

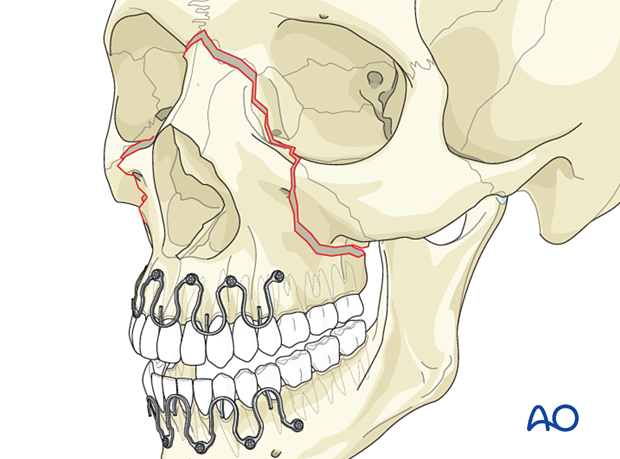

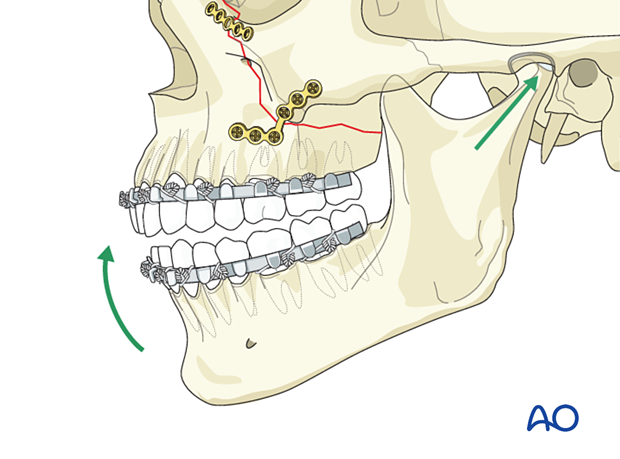

Placing the patient into MMF

After the fracture has been adequately mobilized, the patient is placed in MMF. Click here for a detailed description of various MMF techniques.

Following reduction and fixation of the mandibular fractures, the MMF is released, allowing the condyles to sit passively in the glenoid fossa, and occlusion confirmed.

4. Fixation

General considerations

Depending on the quality and stability of the reduction, the final decision is made regarding the number of plates and screws and the plates’ design.

Fixation usually starts at the most reliably reduced buttress, always considering any fracture line in all three dimensions. If the reduction is satisfactory, the first plate can be fixed with an adequate number of screws. Due to specific patient injury patterns, provisional fixation with a limited number of screws may be indicated (in special cases, even temporary wire fixation might be considered). Two screws per fracture side should be attempted.

The remaining buttresses are similarly addressed.

Complete reduction and fixation of the Le Fort fractures should take place before addressing the orbital wall fractures.

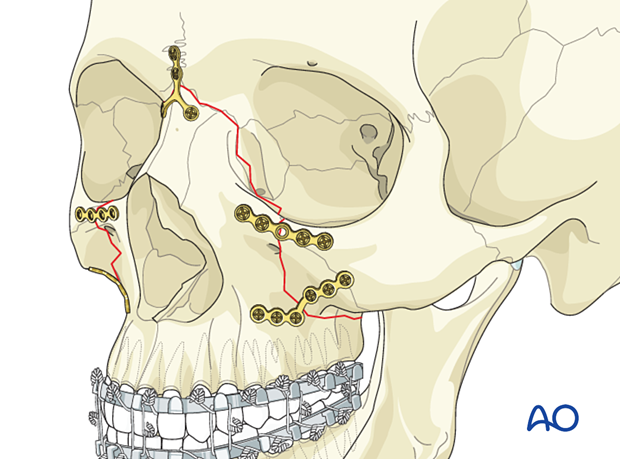

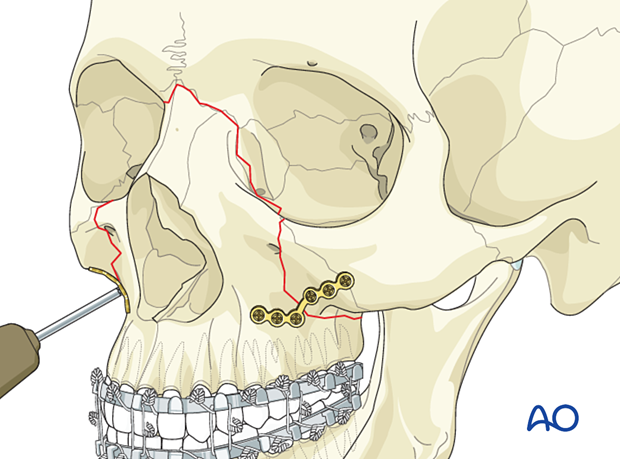

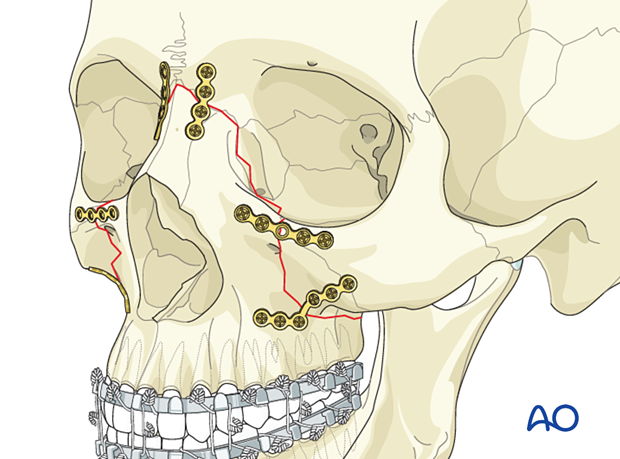

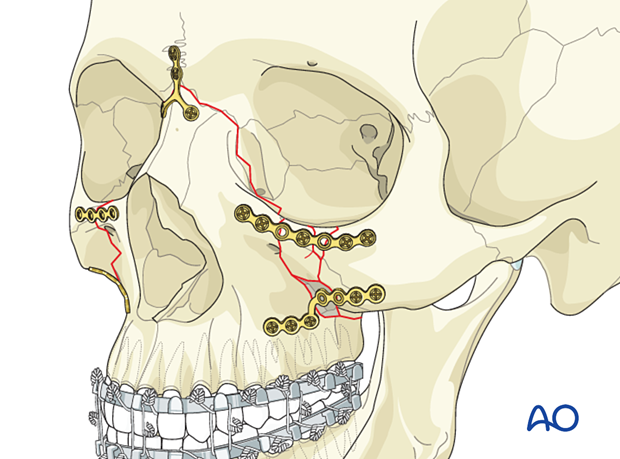

First plate

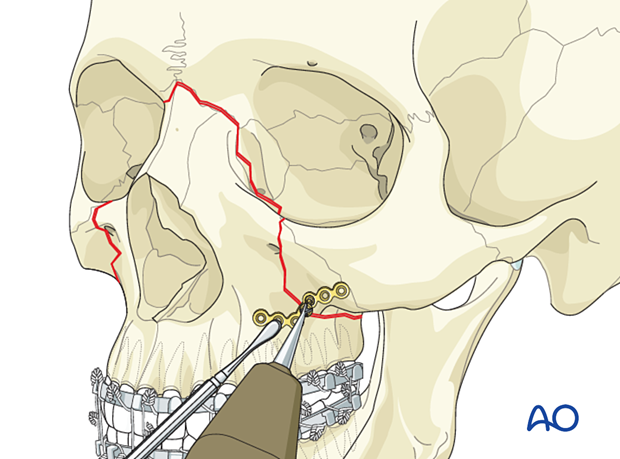

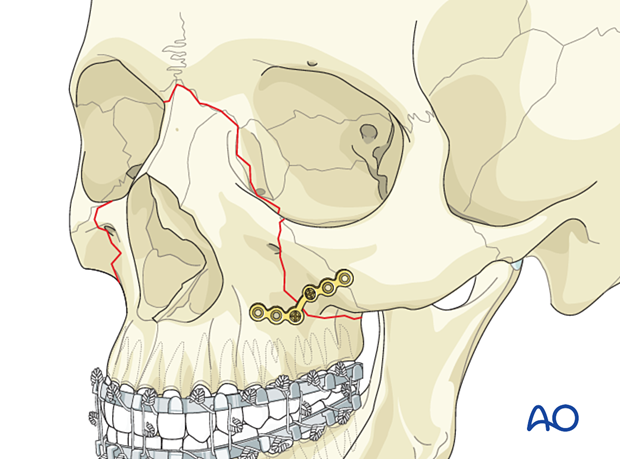

All the plates need to fit passively. In the case shown, the first plate is applied to the left zygomaticomaxillary buttress. According to the particular fracture morphology, a plate of appropriate profile, shape, and length is selected and contoured using bending pliers. This is the most difficult plate to adapt properly.

The plate is positioned with appropriate instruments (eg, forceps, plate holders, gauze packer). The first hole is drilled (a drill bit with a stop can be used) next to the fracture line in the zygomatic complex, and a screw is inserted.

A large L-shaped plate is ideal for the fixation of this fracture site. The vertical arm of the plate must be placed on the most lateral portion of the zygomaticomaxillary buttress, where the bone is fairly thick.

It is also important that the horizontal arm of the plate is placed along the alveolar bone so that the screws are not placed into the tooth roots. A common problem with this plate is the failure to appropriately position the L-plate, resulting in screw placement into the thin wall of the anterior maxillary sinus. It is not uncommon for the lateral maxillary buttress to be comminuted. In this instance, using a longer-span L-plate may be ideal.

After drilling, the second screw is inserted next to the fracture line on the opposite side of the fracture. Care must be taken not to damage the tooth roots.

If the reduction is satisfactory at the other fracture lines, the remaining screws are inserted (at least two screws per fracture fragment).

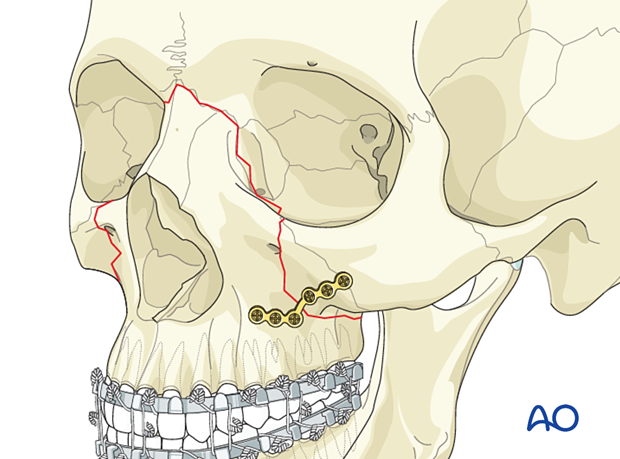

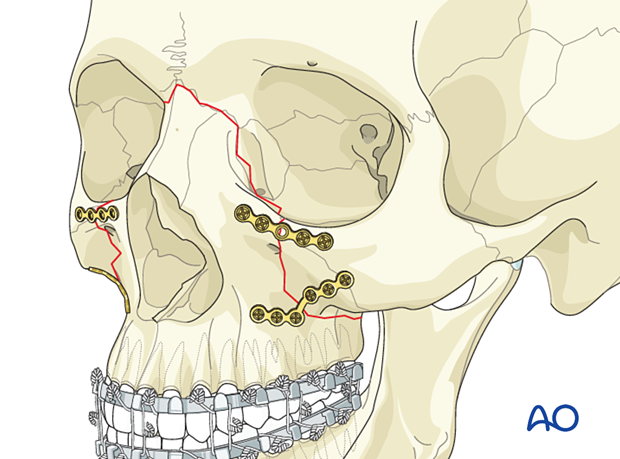

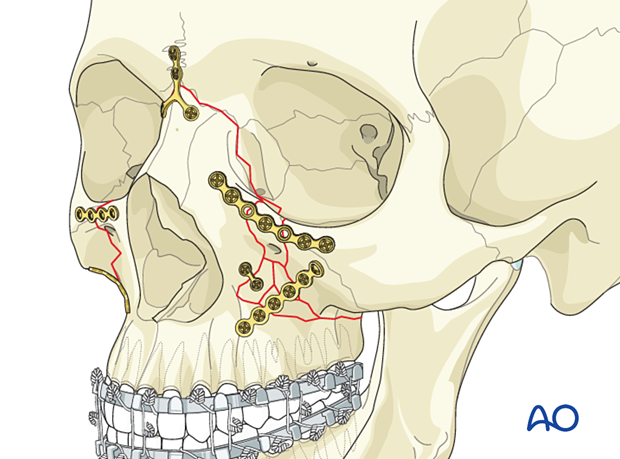

Plating the contralateral zygomatic buttress

In the illustrated case, the contralateral alveolar zygomatic crest/buttress is fixed in the same manner.

At this point, a decision must be made whether or not the two plates at the zygomaticomaxillary buttress provide sufficient stability to the repositioned Le Fort II segment. At this point the MMF is released, and the occlusion is checked prior to the placement of additional fixation plates. The remainder of the fracture sites are then addressed with plate and screw fixation. The occlusion is checked one final time prior to closure of the incisions.

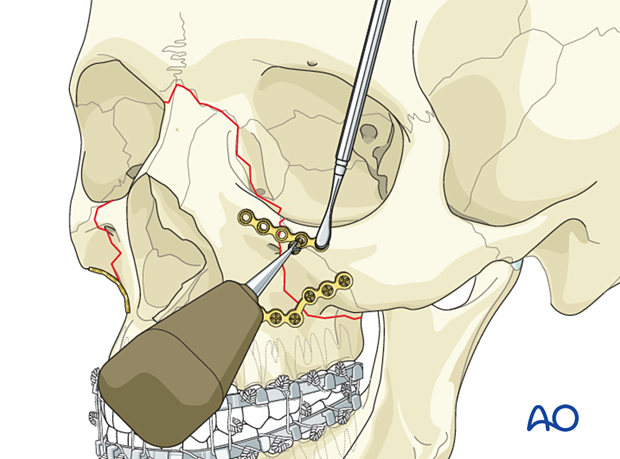

Plates at infraorbital rim

Two contoured plates of appropriate profile and length are selected, adapted, and applied to the infraorbital rims.

The first screw is inserted in the stable fragment (ie, the lateral fragment) next to the fracture line.

The remaining screws of the first and second plate are applied accordingly.

At this point, a decision must be made whether or not the plates at the zygomaticomaxillary buttress and the infraorbital rims provide sufficient stability to the repositioned Le Fort II segment. If so, the MMF is released, and the occlusion is verified.

If the fracture is unstable, the frontonasal suture needs to be plated.

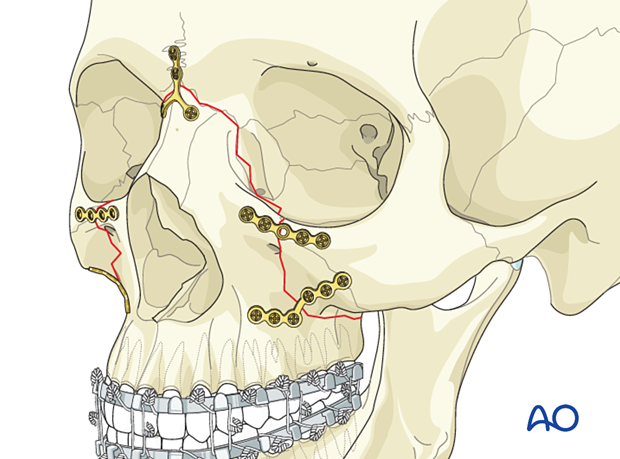

Nasofrontal plate(s)

Depending on the fracture pattern, an appropriate plate or plates is/are selected. In the illustrated case, a Y-plate is used to stabilize the nasal skeleton.

In the illustrated case, two plates are used for further reduction and stability of the nasal skeleton.

Check occlusion

After internal fixation has been completed, MMF is released, and the occlusion is checked.

The occlusion is checked with a patient out of MMF with the fingers on the mandible seating the condyles in a posterior superior position within the glenoid fossa.

If a malocclusion such as an anterior open bite is noted at this time, a revision of the reduction must be performed to reestablish the proper occlusion.

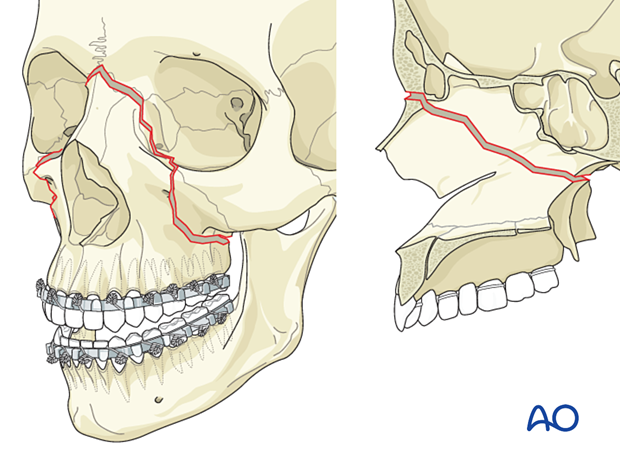

Pitfall: malocclusion

If an open bite or Class III tendency occurs when checking the occlusion, one or both mandibular condyles are malpositioned in the posterior or inferior direction. In such cases, it is necessary to remove the bone plates, reapply MMF, and passively reposition the maxillomandibular complex, ensuring the condyles are properly seated. Bone plates are then reapplied, and the occlusion is verified.

The reason for the malocclusion may be that the condylar heads were not properly positioned in their respective glenoid fossae when the MMF was initially applied (as illustrated).

The illustration shows the subsequent malocclusion after release of the MMF.

5. Comminuted fractures

Introduction

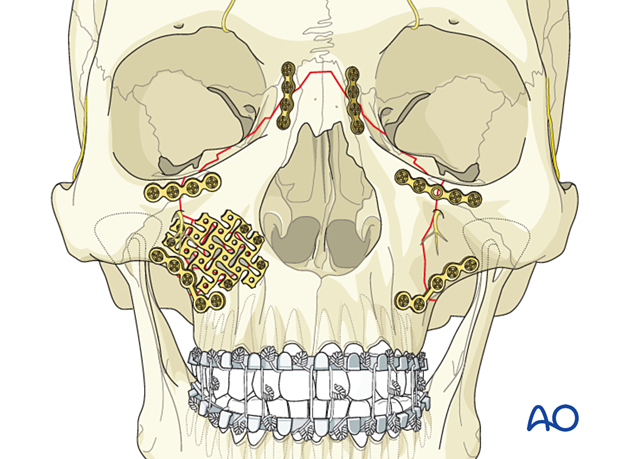

Le Fort II fractures can be comminuted. This is especially challenging if the buttresses are affected by the comminution zone. The appropriate fixation technique depends on the location of the comminution and the degree of comminution.

The principle is to place two screws in the good bone beyond the comminuted area. A single screw may be placed in the comminuted pieces.

Comminution of buttresses

If the comminuted area affects the buttresses, the defects have to be bridged with plates of appropriate length and rigidity.

Comminution of the facial maxillary sinus wall

If the comminution affects the facial maxillary sinus wall, the first step is to reduce or even remove fragments compressing the infraorbital nerve.

Fracture fixation depends on the fracture morphology. If the fracture fragments can be reduced, one or more low profile plates are sufficient to keep the fragments in place.

Following a comminuted fracture of the anterior maxillary sinus, the most critical structures to reconstruct are the framework of this portion of the midface, which includes the following buttresses:

- Paranasal (piriform) aperture

- Infraorbital rim

- Zygomaticomaxillary buttress

- Alveolar segment

If the above four structures are appropriately reduced, the skin drapes over them like a canvas on a frame. If there is a defect that remains in the center of these four buttresses, it is the equivalent of a Caldwell-Luc defect. Many surgeons feel that the maxillary sinus does not need to be treated. A significant number of others feel that the defect should be reconstituted by retrieving bone fragments and placing them with fixation in the proper position of the maxillary sinus wall or by adding a suitably designed bone graft. In both this illustration and the next, the surgeon has chosen to reconstruct the Caldwell-Luc defect.

If there is a large defect of the facial maxillary sinus wall, the defect may be bridged by a titanium mesh to reconstruct the original contour and thus support the overlying soft tissues. The use of large mesh implants over sinus defects may lead to late infection and plate-related problems including plate extrusion.

6. Aftercare

Patient vision is evaluated as soon as awakening from anesthesia and then at regular intervals until hospital discharge.

A swinging flashlight test may serve in the unconscious or noncooperative patient; alternatively, an electrophysiological examination must be performed but this is dependent on the appropriate equipment (VEP).

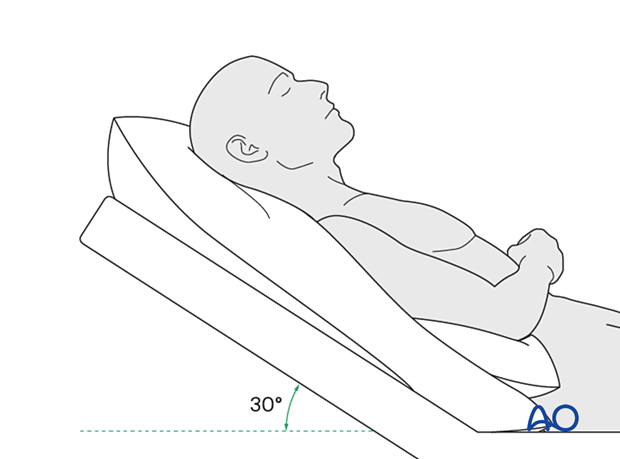

Postoperative positioning

Keeping the patient’s head in an upright position both preoperatively and postoperatively may significantly reduce periorbital edema and pain.

Nose-blowing

Nose-blowing should be avoided for at least ten days following orbital fracture repair to prevent orbital emphysema.

Medication

The following medications may be used:

- Analgesia as necessary (no aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for seven days).

- Antibiotics: many surgeons use perioperative antibiotics. There is no clear advantage of any antibiotic, and the recommended duration of treatment is debatable.

- A nasal decongestant may be helpful for symptomatic improvement in some patients.

- Steroids, in cases of severe orbital trauma, may help with postoperative edema. Some surgeons have noted increased complications with perioperative steroids.

- Regular perioral and oral wound care must include disinfectant mouth rinse, lip care, etc.

Ophthalmological examination

Postoperative examination by an ophthalmologist may be requested. The following signs and symptoms are usually evaluated:

- Vision

- Extraocular motion (motility)

- Diplopia

- Globe position

- Perimetric examination

- Lid position

- If the patient complains of epiphora (tear overflow), the lacrimal duct must be checked

Postoperative imaging

Postoperative imaging may be considered. 2D and 3D imaging (CT, cone beam) are recommended to assess complex fracture reductions. An exception may be made for centers capable of intraoperative imaging.

In fractures involving the alveolar area, orthopantomograms (OPG) are helpful.

Wound care

Remove sutures from the skin after approximately five days if non-resorbable sutures have been used.

Apply ice packs (may be effective in the short term to minimize edema).

Avoid sun exposure and tanning to skin incisions for several months.

Diet

Diet depends on the fracture pattern.

Patients in MMF will remain on a liquid diet until the MMF is released.

Clinical follow-up

Clinical follow-up depends on the complexity of the surgery and whether the patient has any postoperative problems.

With patients that have fracture patterns that include periorbital trauma, consider the following issues:

- Globe position

- Double vision

- Other vision problems

Other issues to consider are:

- Facial deformity (including asymmetry)

- Sensory nerve compromise

- Problems of scar formation

Issues to consider with Le Fort fractures, palatal fractures, and alveolar ridge fractures include:

- Problems of the dentition and dental sensation

- Problems of occlusion

- Problems of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), such as lack of range of motion, pain

MMF

The duration and use of MMF are controversial and highly dependent on the particular patient and the complexity of the trauma. In some cases, MMF may be recommended for 4–6 weeks.

The need and duration of MMF are very much dependent on:

- Fracture morphology

- Type and stability of fixation (including palatal splints)

- Dentition

- Coexistence of mandibular fractures

- Premorbid occlusion

Oral hygiene

Patients with arch bars, intraoral incisions, or wounds must be instructed about appropriate oral hygiene procedures. The presence of arch bars or elastics makes oral hygiene more complicated. A soft toothbrush (dipped in warm water to make it softer) should be used to clean the teeth and arch bars. Elastics are removed during oral hygiene procedures. Disinfectant mouth rinses (Chlorhexidine) should be prescribed and used at least three times a day to help sanitize the mouth.

For larger debris, a 1:1 mixture of hydrogen peroxide/Chlorhexidine can be used. The effervescent action of the hydrogen peroxide helps remove debris. A jet irrigator, (eg, Waterpik) is a handy tool to help remove debris from the wires. If used, care should be taken not to directly point the jet stream over intraoral incisions, which may lead to wound dehiscence.

Follow-up

The patient needs to be examined and reassessed regularly and often. Additionally, ophthalmological, ENT, and neurological/neurosurgical examinations may be necessary.

Special considerations for orbital fractures

Travel in pressurized aircraft is permitted following orbital fractures. Mild pain on descent may be noticed. However, flying in a non-pressurized plane should be avoided for a minimum of six weeks.

No scuba diving should be permitted for at least six weeks.