Coronal approach

1. Principles

General consideration

The coronal or bitemporal approach is used to expose the anterior cranial vault, the forehead, and the upper and middle regions of the facial skeleton. The extent and position of the incision and the layer of dissection depend on the particular surgical procedure and the anatomic area of interest. The coronal approach is placed remotely to avoid visible scars.

Either the subperiosteal or subgaleal planes are commonly used for coronal flap dissection. The scalp incision can be extended inferiorly into the preauricular region to gain access to the zygomatic arch and temporomandibular joints (TMJ). To protect the temporal branch of the facial nerve when the zygoma and the zygomatic arch are accessed, the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia is divided along an oblique line from the level of the tragus to the supraorbital ridge to enter the temporal fat pad. The dissection below this fascial splitting line is carried out just inside the fat pad deep to the superficial layer of temporalis fascia until the zygomatic arch and zygoma are exposed in a subperiosteal plane.

AO teaching video

Video about the coronal approach, including surgical demonstration.

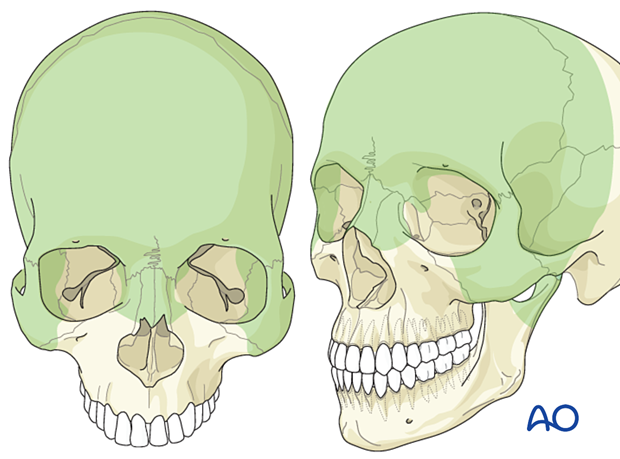

Access areas

The following areas can be exposed:

- Entire calvarial vault

- Anterior and lateral skull base

- Frontal sinus/ethmoid

- Zygoma

- Zygomatic arch

- Orbit (lateral/cranial/medial)

- Nasal dorsum

- Temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

- Condyle and subcondylar region

- Medial and lateral canthal ligaments

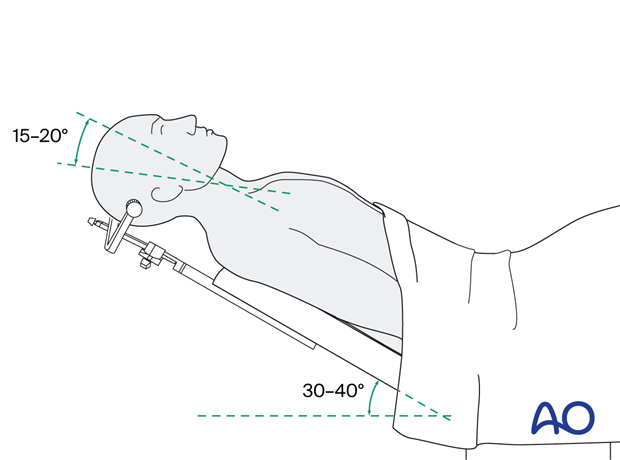

2. Patient position

The patient is placed supine on the operation table. The patient’s body is in a slightly upright position (30–40°), and the head is in 15–20° retroflexion.

In cases of neurotrauma, it is preferable to fix the head in a head clamp.

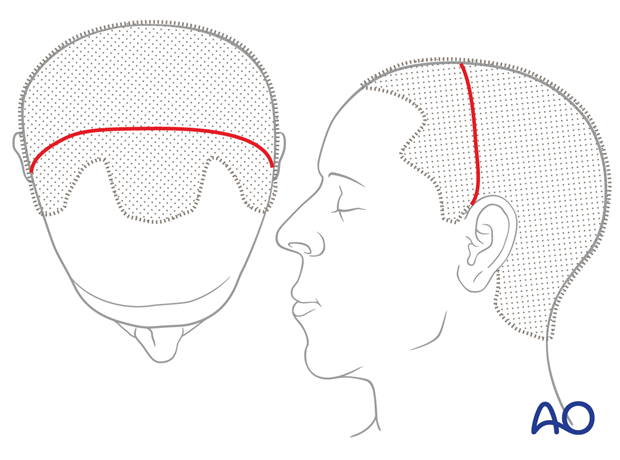

3. Locating the incision line and preparation

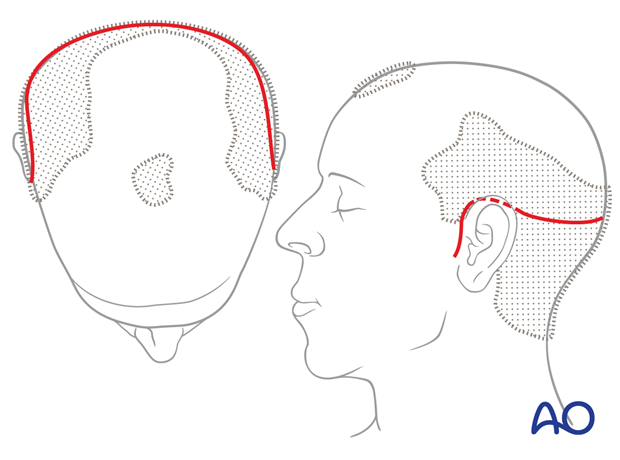

Locating the scalp incision line

The design of the incision line takes account of the hairline of the patient.

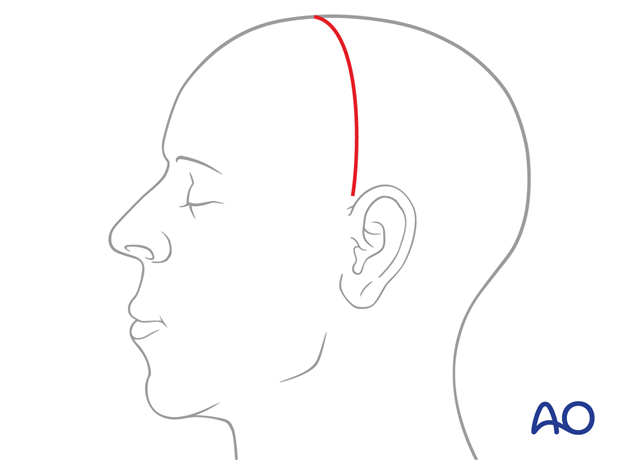

In balding men, the coronal incision line over the scalp and temporal region is placed several centimeters behind the hairline.

For individuals with male pattern baldness, the incision can be placed as far posteriorly as the upper occiput.

Posterior incisions do not reduce access to the operative field. Access depends mainly on the inferior extent of the incision.

In women and men with no family history of balding, the incision may be placed anteriorly over the vertex slightly behind the palpable coronal suture, leaving a 4–5 cm hairline in front.

Inferior extent of incision line

The inferior extent of the incision line depends on the region to be surgically addressed.

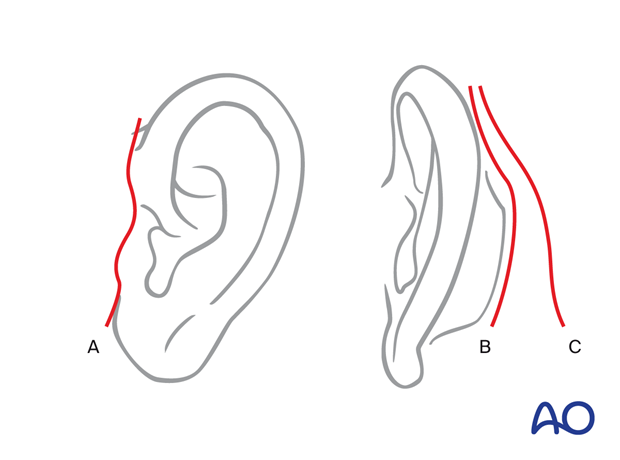

When exposure is limited to the forehead and the supraorbital region, it is sufficient to extend the incision to the level of the auricular helix.

If the zygomatic arch has to be exposed, a pre- (A) or postauricular extension must be added. The extension behind the ear may follow the helical fold (B) or the hairline (C).

If the temporomandibular joint area has to be accessed, a preauricular extension down to the earlobe level is necessary.

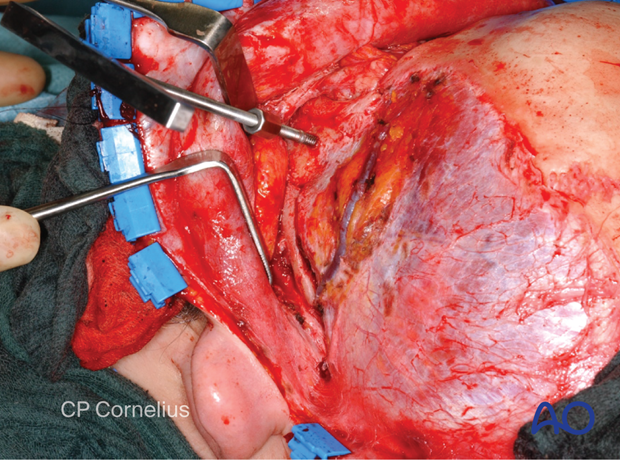

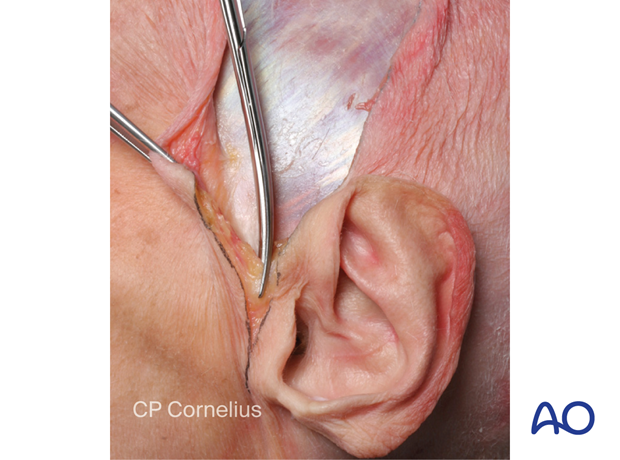

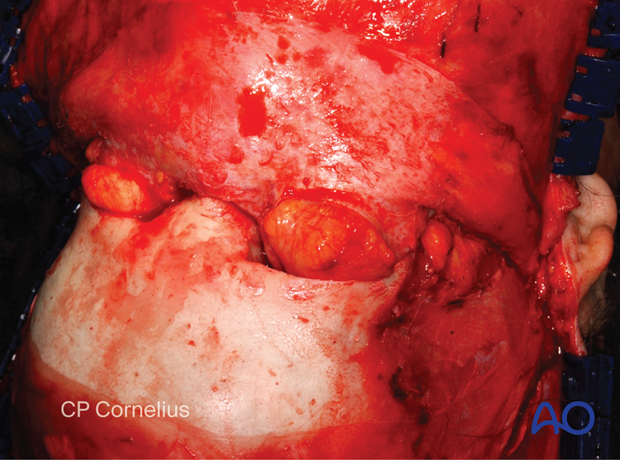

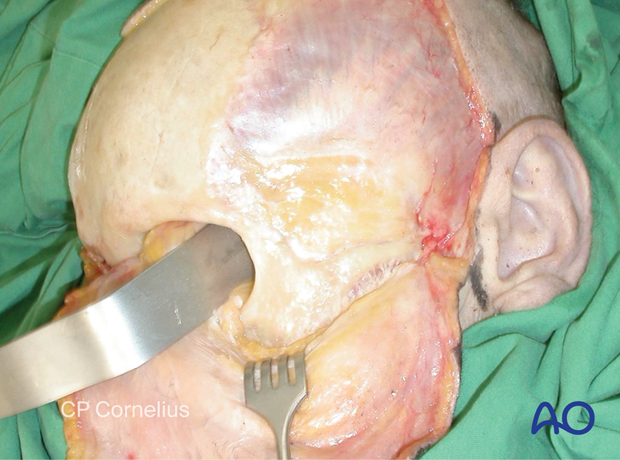

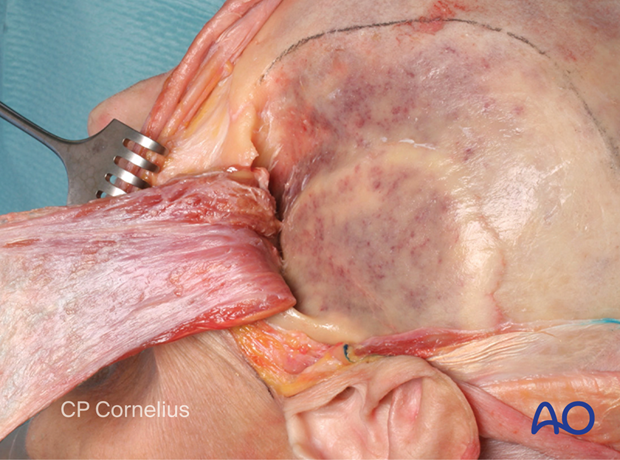

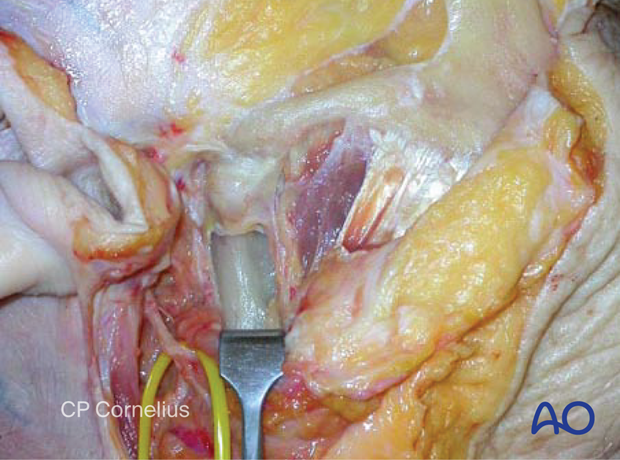

Clinical photograph showing an incision behind the ear along the postauricular fold and the resulting exposure of the zygomatic arch and the zygoma.

Design of incision

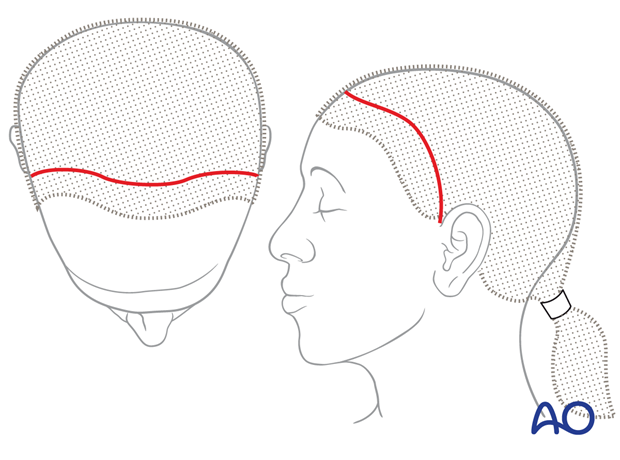

There are several alternatives for the design of the scalp incision.

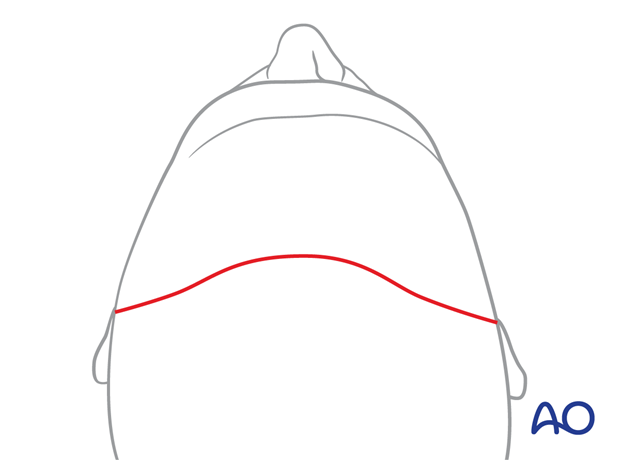

The bow-like incision is traditionally used.

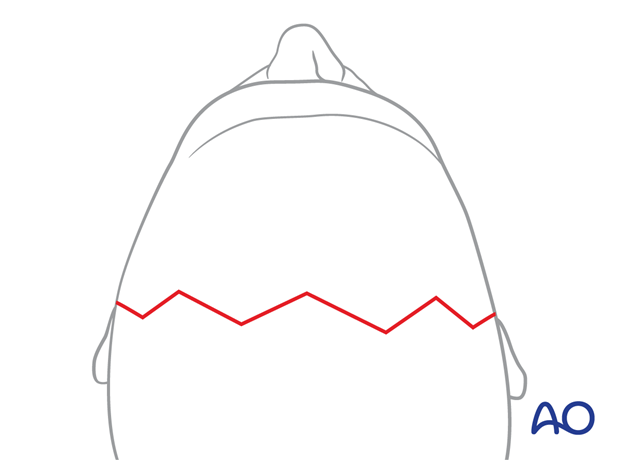

Geometric patterns (zigzag, sawtooth, stepwise, stealth, or wavelike designs) may be used because the scars are less conspicuous, especially when the hair is wet. Furthermore, these types of incisions allow a more accurate reapproximation during closure.

The illustration shows a wave pattern incision design.

Hair preparation without shaving

There is no medical reason to shave the patient’s hair.

Before surgery, the hair is shampooed, gelled, combed, and parted to separate it according to the planned incision line.

Leaving the hair in place will aid in determining the level of the scalp incision to minimize peri-incisional alopecia. This is the principal argument against any shaving of the hair.

The hair is parted, braided, and each braid is secured with elastic bands.

Hair preparation with shaving

It is often convenient to shave a 15–25 mm corridor along the incision line. This facilitates flap handling and wound closure.

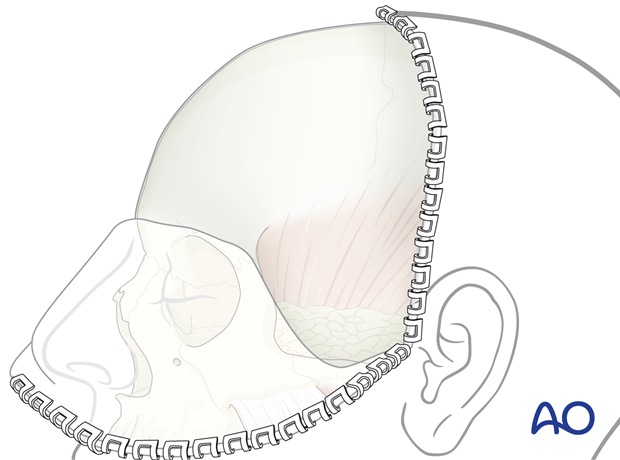

Drapes are sutured or stapled (as shown here) to the scalp posterior to the corridor shaved for the incision.

This covers the hair of the posterior scalp.

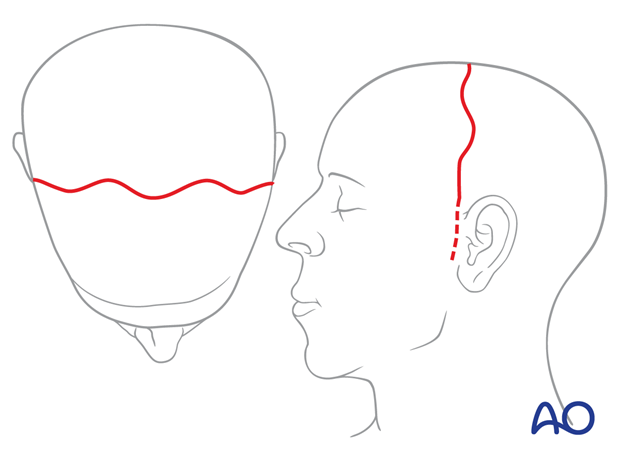

Delineating the sagittal midline and both temporal lines as landmarks help in the layout of a symmetric incision.

The clinical photograph shows the complete drawing of an extended coronal scalp incision in a geometric design.

The dorsal extension over the temporal line serves to preserve the deep branch of the supraorbital nerve and avoid sensory loss in its terminal skin distribution.

4. Hemostatic techniques

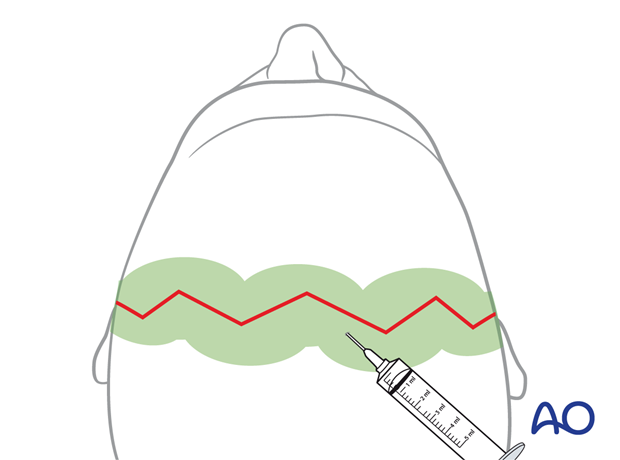

There can be significant blood loss from the coronal incision at the beginning of surgery and during closure. Several techniques may be used to limit blood loss:

- Infiltration of a vasoconstrictor into the subgaleal plane. As illustrated, the scalp is hyperinflated along the whole length of the incision line for hydrostatic tamponade just before the incision.

- Insertion of interrupted deep slightly overlapping sutures parallel to the incision

- Use of hemostatic clips (Raney clips) after the elevation of the wound edges (may lead to ischemia and alopecia)

A combination of these techniques may also be used.

5. Incision

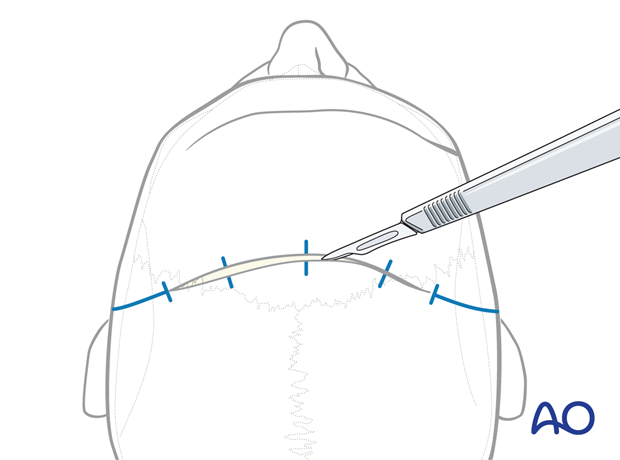

Additional to marking the actual incision line, crosshatches or tattoo dye markings may be helpful to realign the wound edges accurately during the closure of the scalp in cases where a bow-like incision is used.

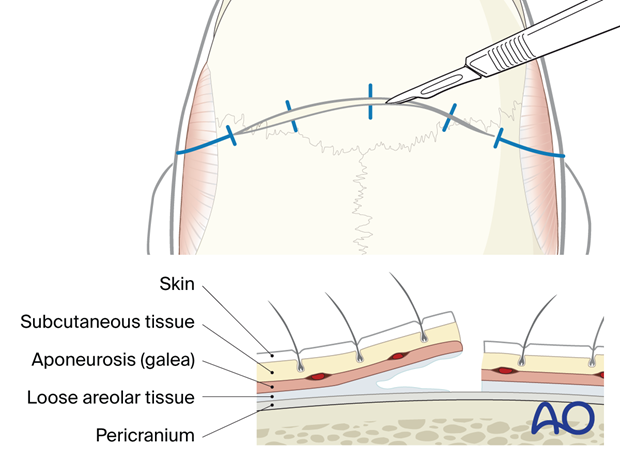

The initial scalp incision extends from one superior temporal line to the other and stays between the upper origins of the temporalis muscles.

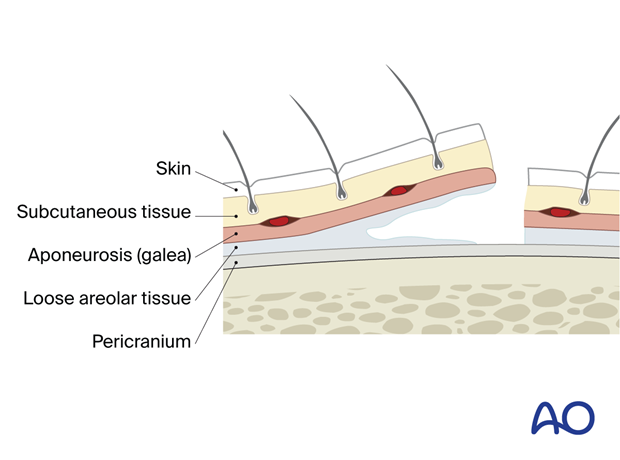

The scalp is the soft-tissue layer of the skull. In simple terms, the scalp consists of five layers at the vertex as seen in the illustration: skin, dense inelastic subcutaneous connective tissue and fat, galea aponeurotica, loose areolar subgaleal tissue, and pericranium.

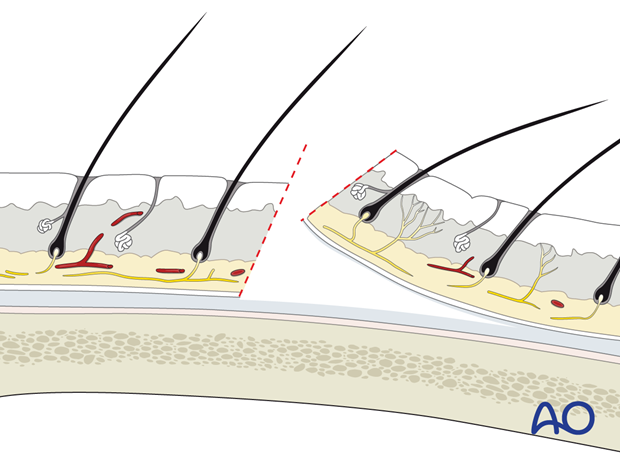

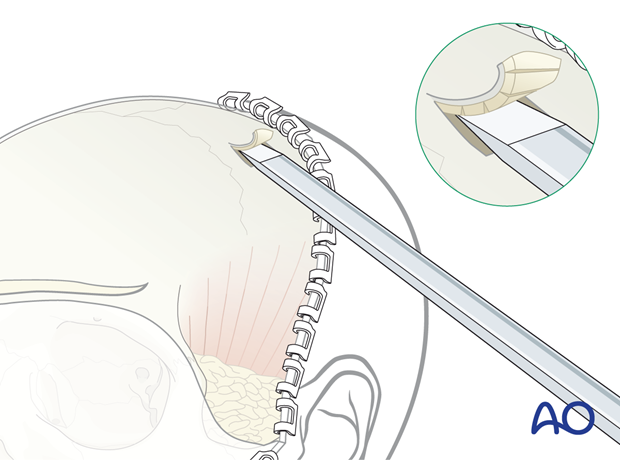

Beveled incision

The incision should be beveled such that it is parallel to the follicles.

The incision is made with a #10 blade to the depth of the pericranium or the bone.

Dissect this flap in either the subgaleal or subperiosteal plane depending on the specific case (need for pericranial flap or fracture location).

The pericranium can be raised as a separate, anteriorly pedicled vascularized flap for reconstructive purposes.

If a pericranial flap is anticipated, the incision stays superficial to the pericranium in the superficial loose areolar plane (galea). The dissection should stop 1 cm to 1.5 cm above the superior orbital rim to preserve vascular connections.

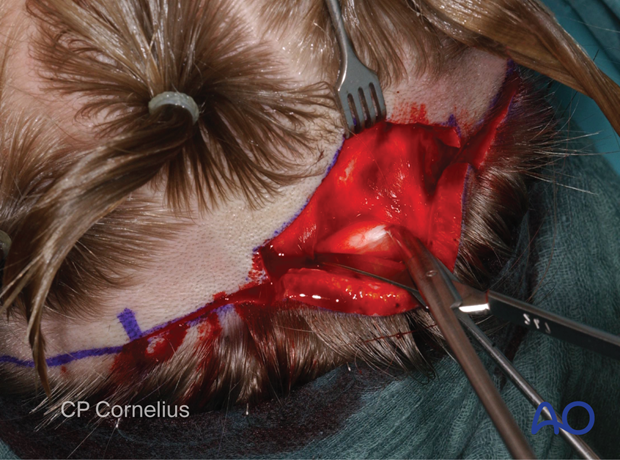

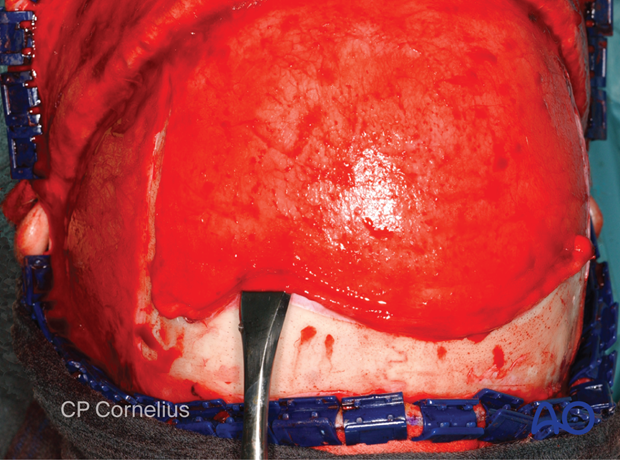

The incision margins are lifted and dissected easily. The dissection either in the subgaleal plane or subperiosteal plane is continued for 2-4 cm anteriorly.

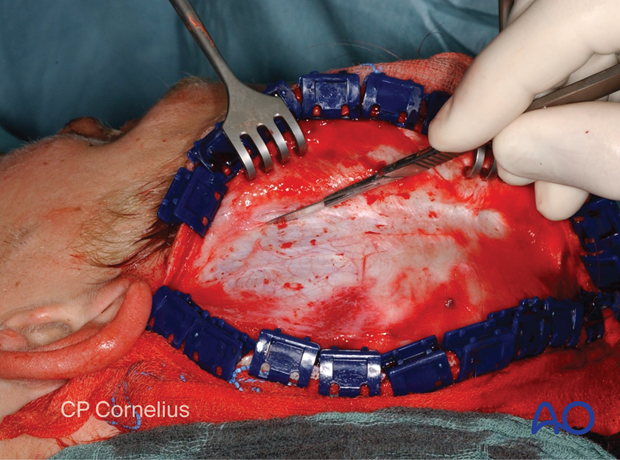

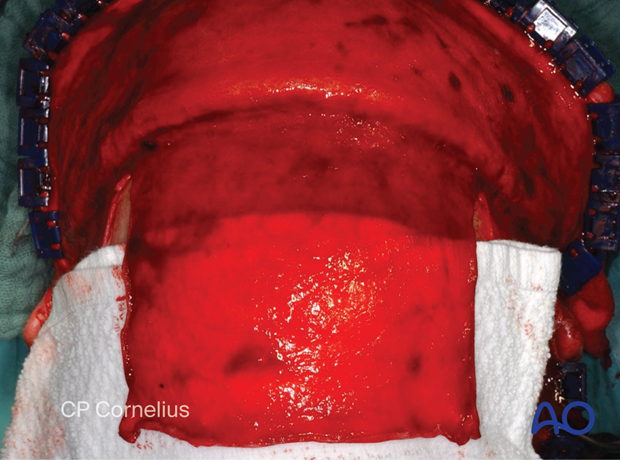

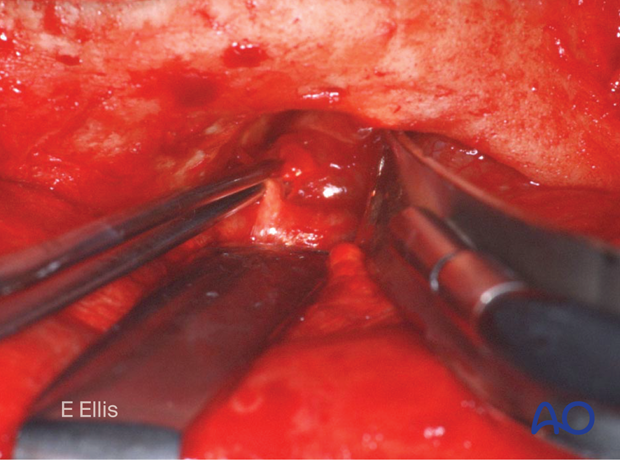

The image demonstrates identification and beginning dissection in the loose areolar tissue of the subgaleal plane.

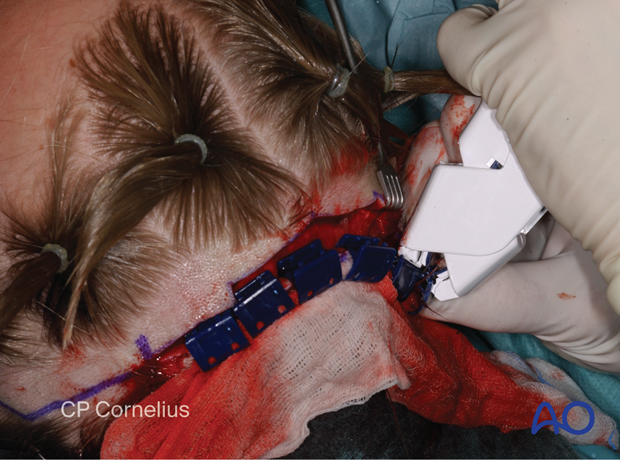

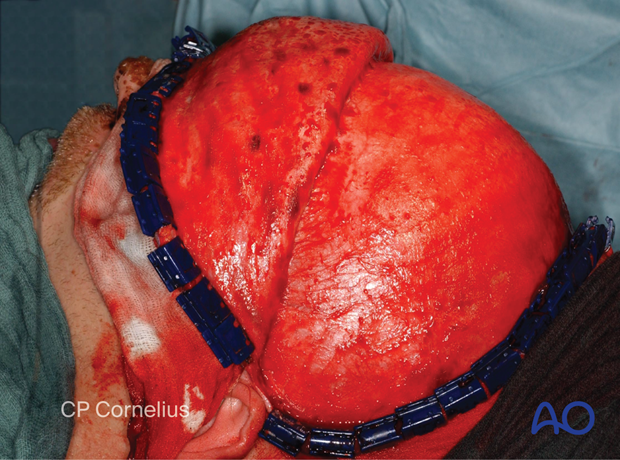

With the raising of the anterior and posterior scalp flaps, bleeding vessels are cauterized, and hemostatic clips (Raney clips) are applied sequentially.

Folded moistened 4x4 gauze sponges are applied along the wound edges prior to clip application to reduce the injury to the soft tissue.

The clinical photograph shows the use of a disposable clip delivery device.

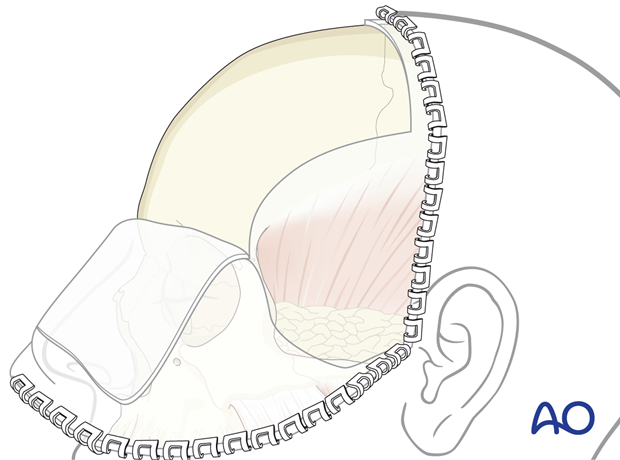

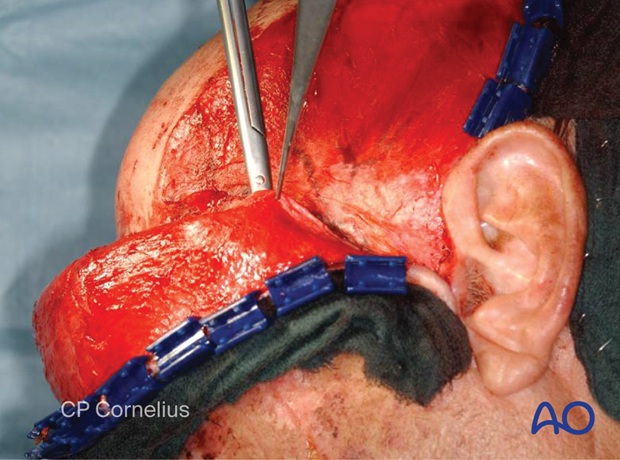

Temporal extension of the skin incision line

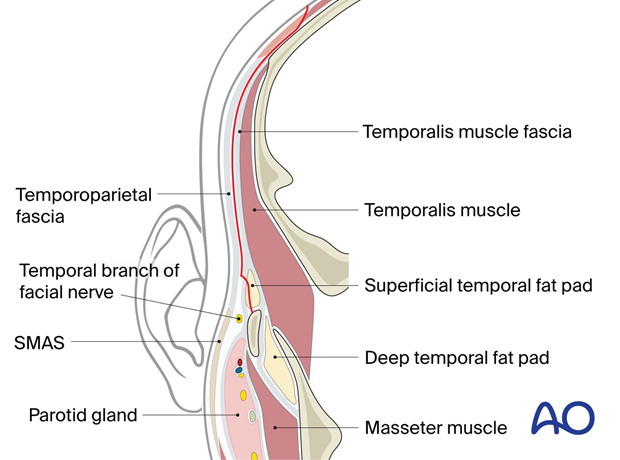

Below the superior temporal line, the subgaleal plane continues deep to the temporoparietal fascia. Continue dissecting on top of the temporalis fascia to the level of the zygomatic arch.

An inadvertent incision through the temporalis fascia into the underlying muscle may result in brisk bleeding.

Traction and countertraction are used to delineate the plane and sharp scalpel dissection is carried inferiorly.

A preauricular extension of the incision can be made within a preauricular crease or anterior to the tragus down to the level of the earlobe.

The skin is undermined to the depth of the temporalis fascia, and the soft-tissue dissection proceeds under meticulous hemostasis with the use of bipolar cautery.

The preauricular muscles are transected, and the cartilaginous portion of the tragus and the external auditory canal may be directly exposed.

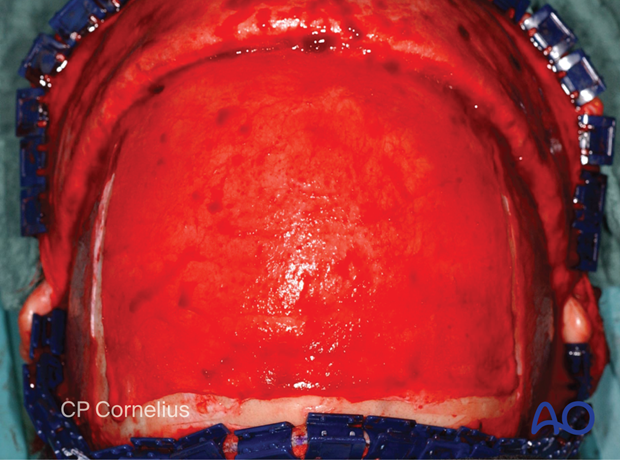

6. Elevation of the coronal flap

The coronal flap elevation proceeds anteriorly with a bilateral dissection. Over the temporalis muscles, the glistening white temporalis fascia is gently exposed with traction and countertraction.

The temporalis fascia fuses with the pericranium at the superior temporal line.

The parietal and forehead portions of the coronal flap are elevated rapidly by cutting the loose areolar connective tissue overlying the pericranium by sharp dissection.

Alternatively, the flap can be elevated readily with finger dissection or a blunt elevator.

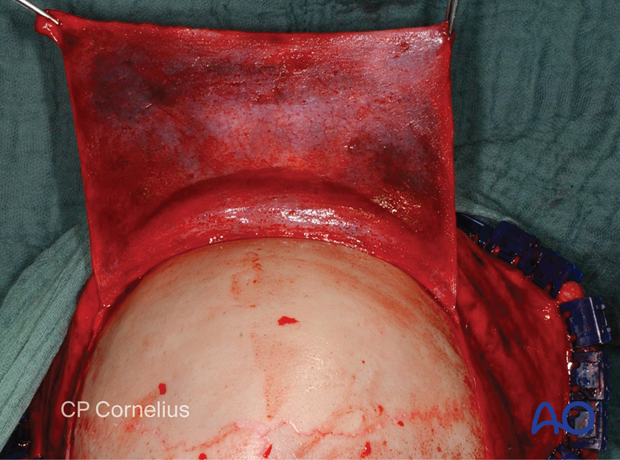

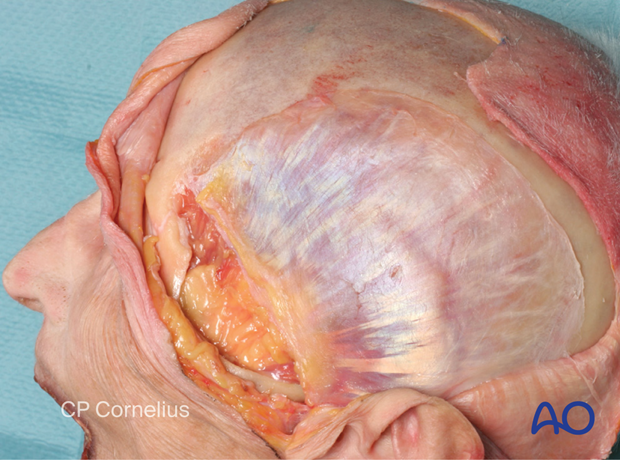

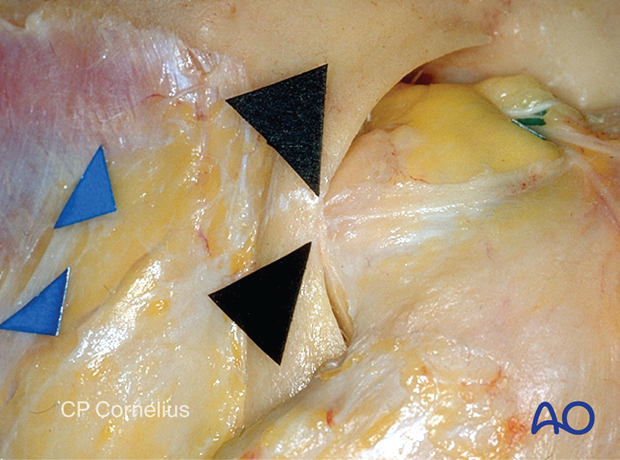

This anatomic specimen shows the glistening white temporalis fascia extending along the lateral aspect of the skull.

The pericranium has been incised at the superior temporal line and raised, attached to the coronal flap from the parietal and forehead areas.

The dissection plane strictly follows the temporalis fascia downwards and forwards just to the zone where the yellow superficial temporal fat pad shines through.

This zone begins in the lower preauricular area at the root of the zygomatic arch, which is palpable and extends across the temporal fossa to the posterior aspect of the zygomatic body.

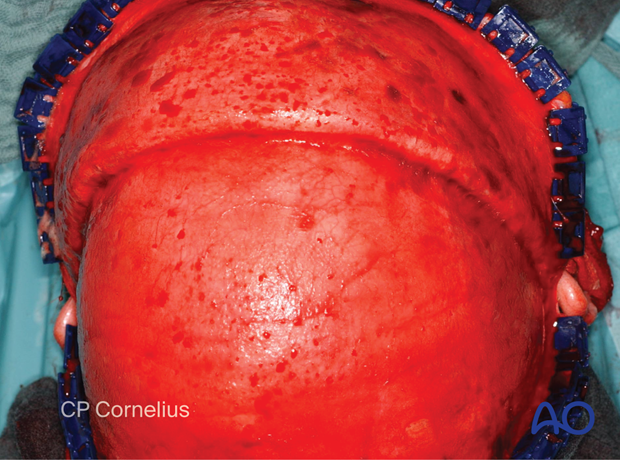

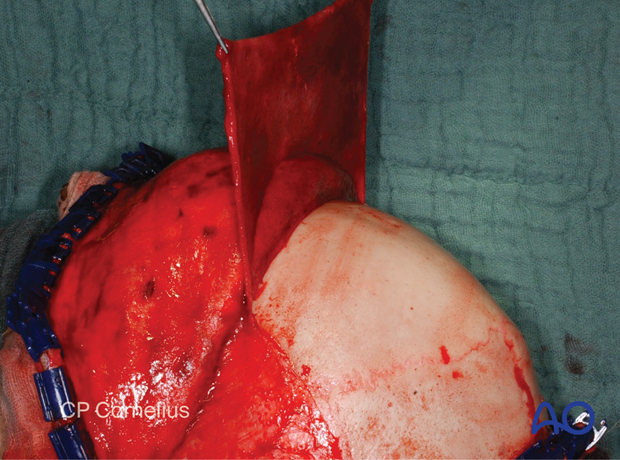

When the coronal flap has been sufficiently released anteriorly and inferiorly, it can be retracted and everted to remain clear of the operative field.

The undersurface of the galea is now superficial to the everted side of the flap.

The dissection of the coronal flap in the subgaleal plane is continued to the level of the supraorbital rims.

If the pericranium has been left on the skull, there are two options to enter the subperiosteal plane and reach the superior orbital rims and expose the facial skeleton:

- Horizontal incision of the pericranium 2-3 cm above and parallel to the supraorbital rims from one superior temporal line to the other

- Posterior and lateral incisions along the superior temporal line of the pericranium to develop a rectangular anteriorly pedicled vascularized pericranial flap

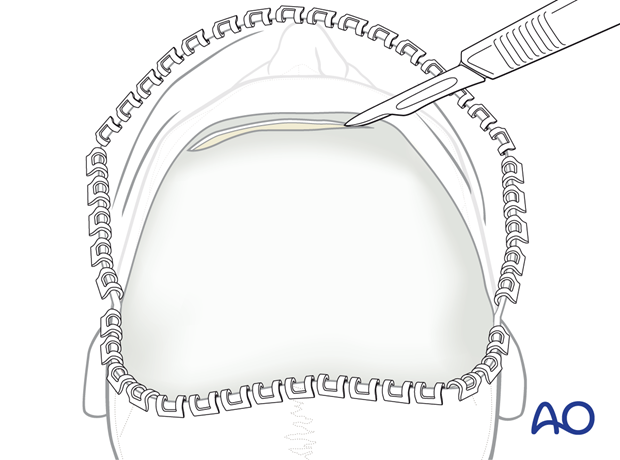

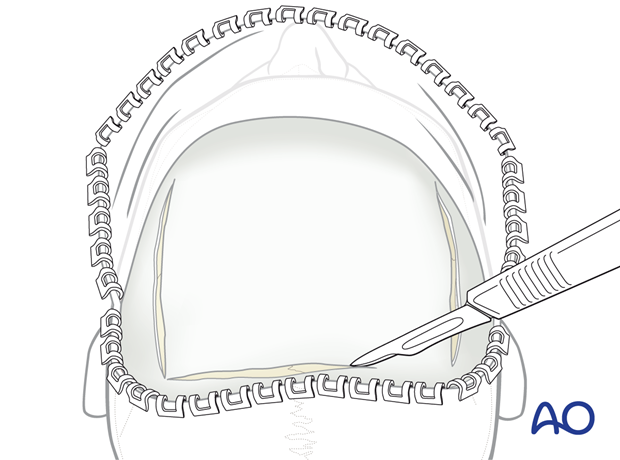

Horizontal incision

For most procedures of the facial skeleton, the pericranium is incised horizontally across the forehead at a point 2–3 cm above the supraorbital ridges.

The incision extends from one superior temporal line to the other, and subperiosteal dissection proceeds forward and downward.

An extension further laterally beyond the superior temporal line requires an incision through the periosteum of the zygomatic process of the frontal bone.

Such an extension releases the tension and facilitates tissue retraction necessary to expose the nasofrontal and supraorbital regions.

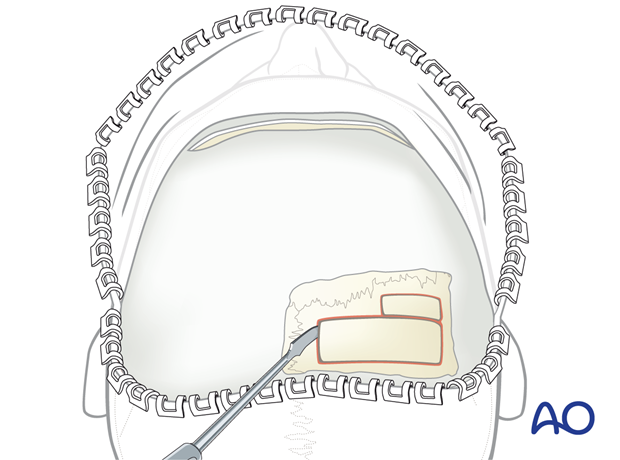

7. Development of pericranial flap

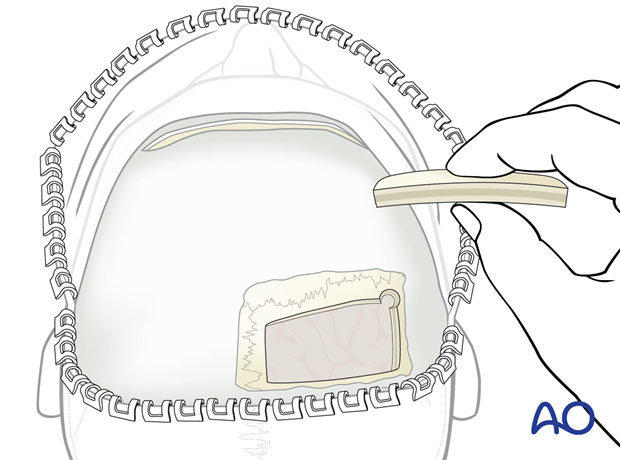

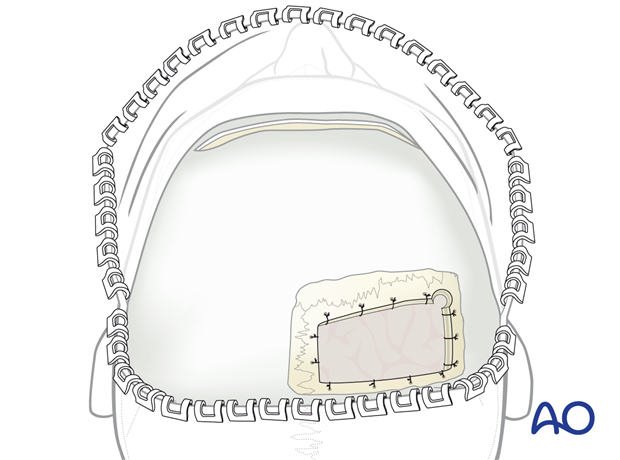

When the frontal sinus or anterior cranial base is to be reconstructed, it is advisable to develop a pericranial flap.

An anteriorly based pericranial flap is very versatile and can be used to seal the nasal cavity in frontal sinus reconstruction, closure, obliteration of anterior skull base defects, etc.

The pericranial flap is vascularized by the deep branches of the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries, which course between the galea-frontalis muscle layer and the pericranium.

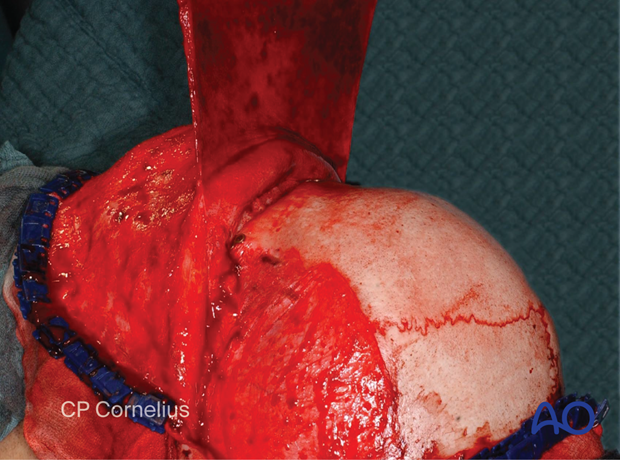

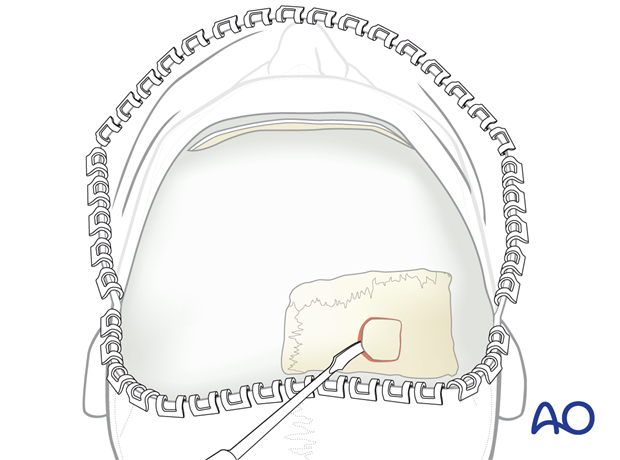

After supraperiosteal dissection of the coronal flap, the pericranium is incised and elevated from the skull.

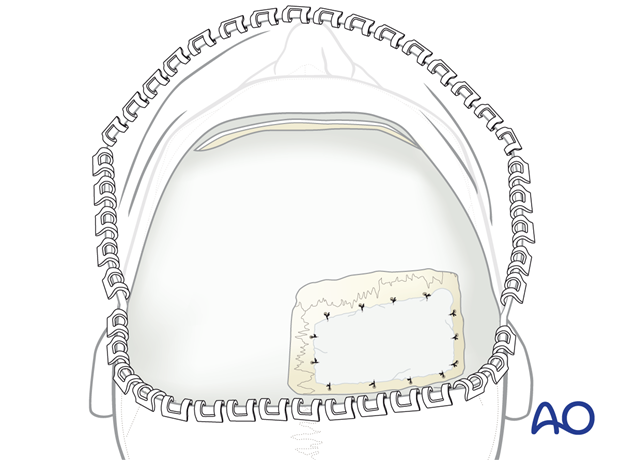

The incisions through the pericranium are made bilaterally along the superior temporal lines from the anterior to the posterior extent of the exposed surface. This allows the development of a large rectangular flap, as illustrated.

The image demonstrates bilateral incisions along the superior temporal lines from the anterior to the posterior extent of the exposed surface.

Sharp square periosteal elevators are then used to elevate the pericranial flap. The pericranium adheres loosely and can be raised easily over the parietal and most of the frontal bone. The pericranium is densely connected to the underlying bone in a transverse band about 2.5 cm wide above the orbital rims. Therefore, care must be taken to avoid tissue tearing during the elevation of the flap in the supraorbital region.

The pericranial flap provides a large apron of well-vascularized tissue that can be used to repair the frontal sinus and anterior skull base.

The reach of the flap increases after subperiosteal dissection of the forehead in the supraorbital region.

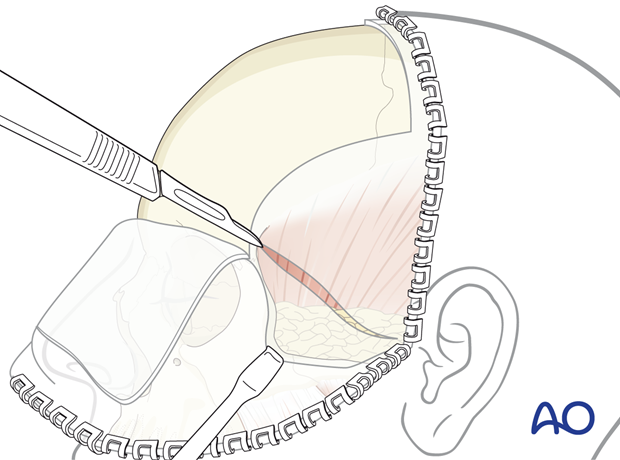

8. Incision of the superficial temporal fascia for exposure of the zygomatic arch

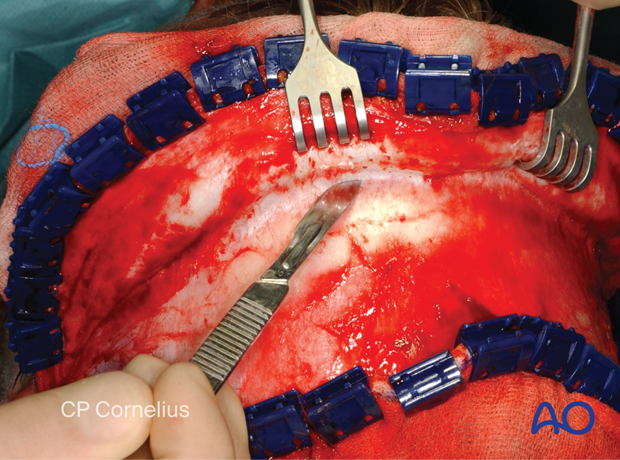

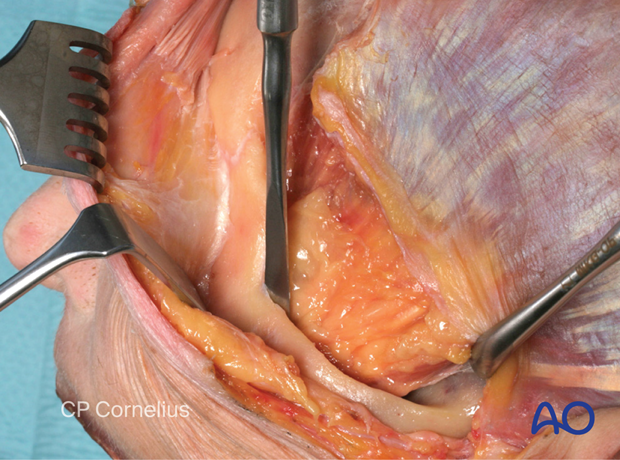

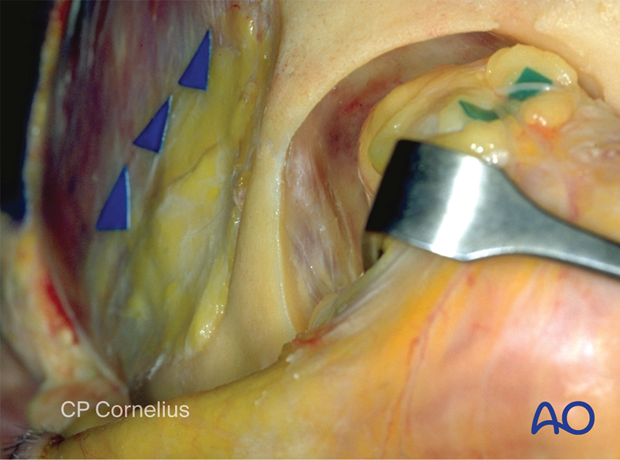

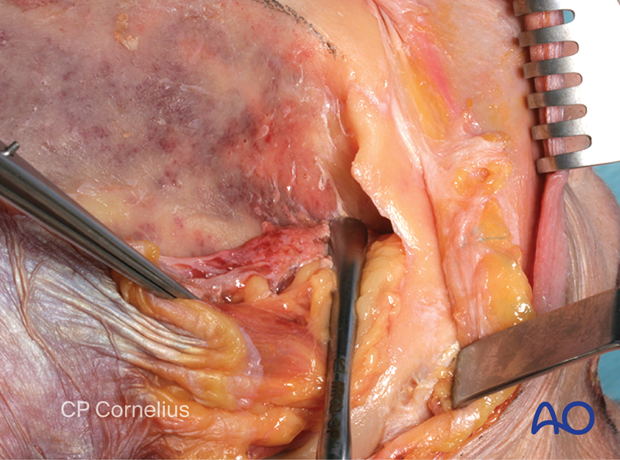

The lateral dissection of the coronal flap is continued from the subgaleal plane of the scalp to the temporal region. The dissection strictly follows the temporalis fascia.

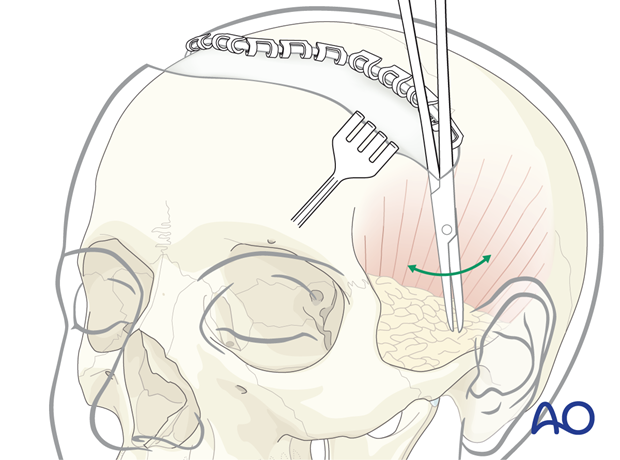

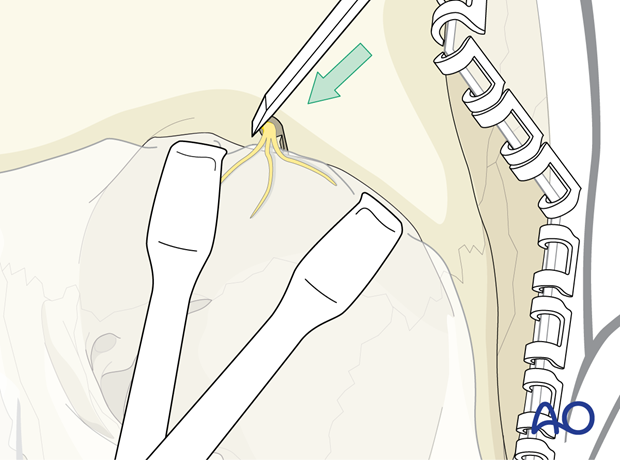

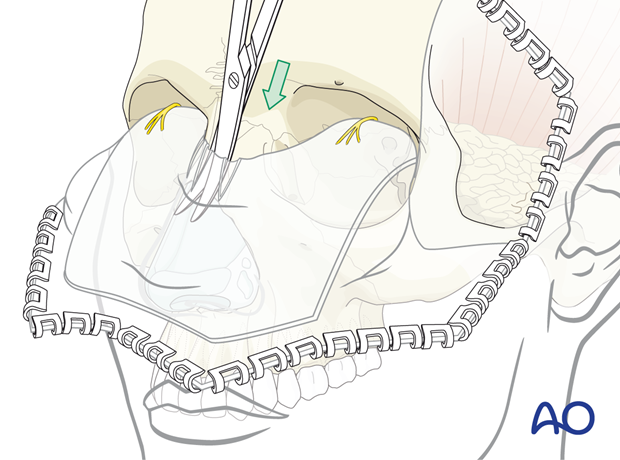

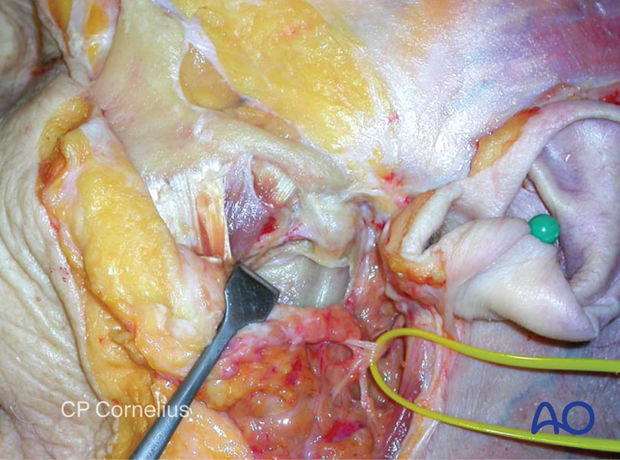

As soon as the yellow outline of the superficial temporal fat pad is visible shining through the superficial layer of temporalis fascia, an oblique incision can be made through the fascia extending from the root of the zygomatic arch to the superior-posterior aspect of the lateral orbital.

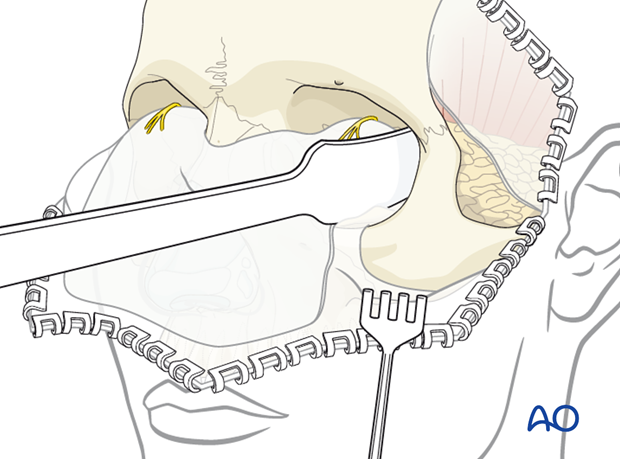

The illustration shows an oblique incision of the superficial layer of temporalis fascia.

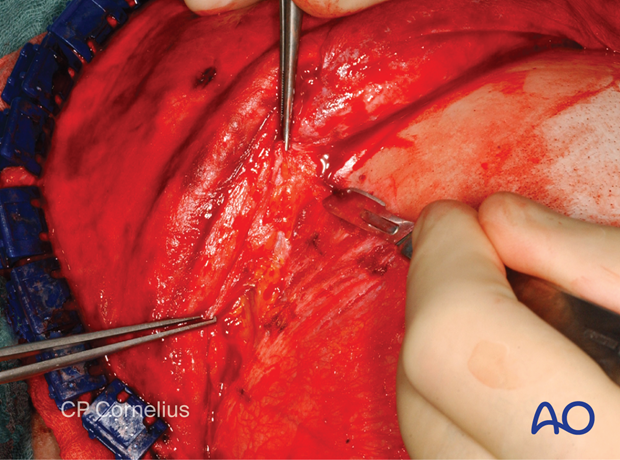

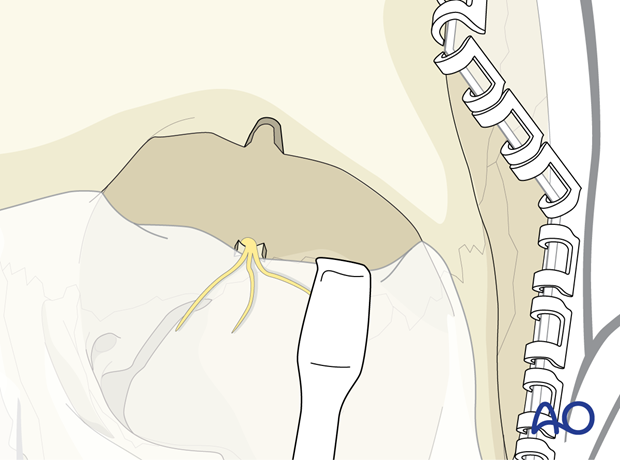

The dissection down to the arch and the root of the zygoma is made superficial to the fat pad right underneath the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia.

This plane can be conveniently discerned using a sharp dissection.

This dissection plane allows for the protection of the temporal branch of the facial nerve, as shown in the illustration.

Alternatively, the elevation of the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia in the dissection to the zygomatic arch can be done bluntly using scissors.

A common complication of the temporal fat pad approach is a hollowing of the temporal fossa, which may represent a significant cosmetic deformity.

The current understanding is that postoperative temporal hollowing is a consequence of fat atrophy caused by devascularization, denervation, or displacement of the fat pad. The dissection should be kept on the lateral surface not to injure the connective tissue septations that suspends the fat pad and to prevent inferior sagging.

Transection of the zygomaticotemporal nerve branches perpendicular through the fat pad is unavoidable.

The superficial layer of the temporalis fascia is progressively dissected in an anterior direction and then turned laterally to reach the periosteum along the superior surface of the zygomatic arch.

The periosteum is incised at the superior aspect and reflected over the arch, the posterior border of the body of the zygoma, and the lateral orbital rim.

The subperiosteal temporal dissection is connected with the subperiosteal dissection over the lower forehead.

The subperiosteal temporal dissection can also be initiated from the lateral forehead and advanced over the zygomaticofrontal suture.

Subperiosteal dissection of the zygomatic arch and body allows eversion of the coronal flap more anteriorly and inferiorly.

9. Subperiosteal exposure of the orbits and upper midface

Release of the supraorbital neurovascular bundle

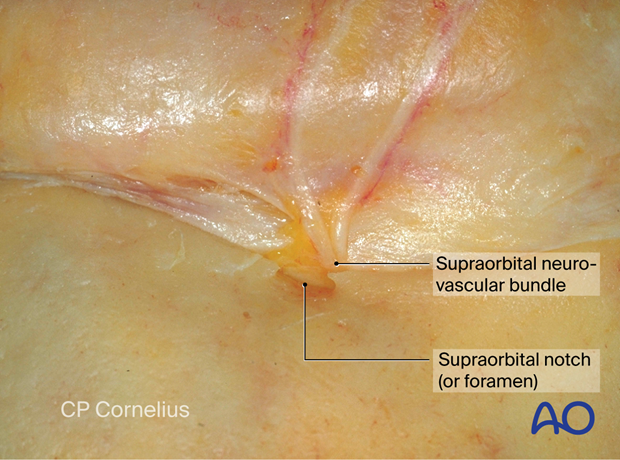

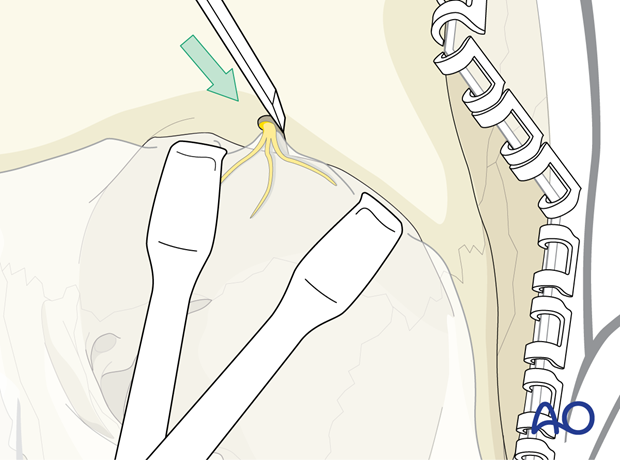

To extend the supraorbital dissection inferiorly to the nasofrontal area and over the orbital rims into the upper circumference of the orbital cavity, it is necessary to release the supraorbital neurovascular bundle, which either exits through a bony foramen or emerges from below the supraorbital notch.

If a supraorbital foramen is found, it is converted into a notch. A fine osteotome, or a piezo surgery tip, can be used to remove a small bony wedge caudal to the neurovascular bundle to allow its release.

Care should be taken to protect the neurovascular bundle during the osteotomy.

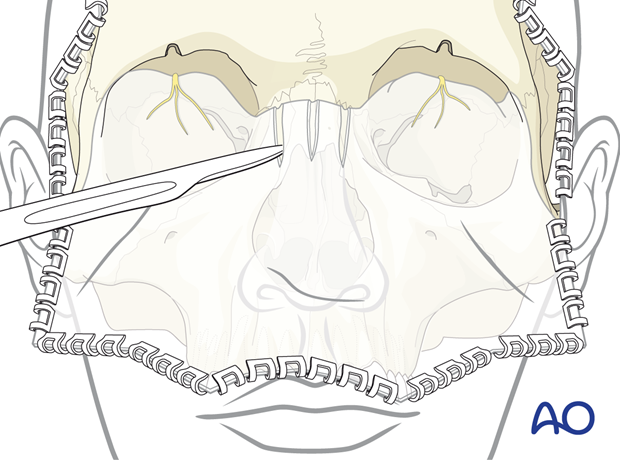

Once the neurovascular bundle has been released from its foramen, a complete subperiosteal dissection is performed, allowing access to the supraorbital rims, nasofrontal area, orbital roof, and medial orbital walls.

If a notch is present, the neurovascular bundle is simply reflected together with the periorbital dissection from the bone as shown. In this example, the trochlea is still attached superomedially next to the shallow supraorbital furrow.

Further retraction of the flap inferiorly is accomplished by subperiosteal dissection into the orbits.

As shown, the periorbita is dissected 180° off the adjacent superior medial and lateral orbital walls into the mid-orbit after the release of the supraorbital nerves. If necessary, the dissection can continue even deeper into the orbit.

For exposure of the nasofrontal and the nasoethmoid region and the medial orbit, the trochlea needs to be disinserted from the frontal bone with its connective tissue attachments.

Short sagittal incisions through the periosteum over the midline of the nasal dorsum will release the soft-tissue tension and facilitate the retraction of the coronal flap down to the osteocartilaginous junction between the nasal bones and the upper lateral cartilages.

Dissection to the tip of the nose can then be readily carried out with Metzenbaum scissors.

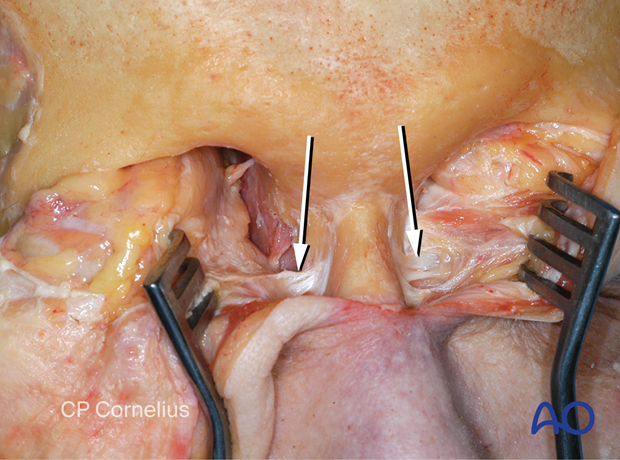

The elevation of the periorbita from the lateral orbital wall detaches the lateral canthal tendon closely connected to the periosteum over the lateral orbital rim (black arrows in the anatomic specimen) and lateral orbital tubercle (Whitnall).

Dissection deep into the lateral orbit exposes the suture line between the orbital flange of the zygoma and the greater wing of the sphenoid (zygomaticosphenoid suture).

The image shows the dissection of the lateral orbital wall to the zygomaticosphenoid suture.

The dissection of the lateral orbital wall is demonstrated in a clinical case.

The lateral subperiosteal dissection can be continued from the lateral orbital rim downward over the body to the inferior border of the zygoma.

Medial extension at this level provides exposure of the lateral half of the infraorbital rim to the infraorbital nerve and foramen.

This approach allows access to the lateral floor of the orbit.

It is advantageous to complement the coronal flap approach with transcutaneous or transconjunctival incisions in the lower eyelid for full access to the orbital floor and the medial half of the infraorbital region.

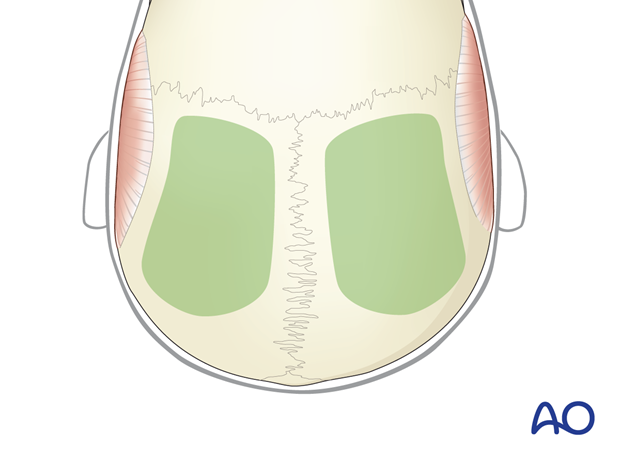

This illustration demonstrates the extended midfacial exposure that can be obtained through a coronal approach.

The anterior fibrous and muscular components of the medial canthal tendon fan out medially and insert into the nasofrontal maxillary process (arrows).

The anterior branch of the medial canthal tendon is identified as a firm fibrous strand (arrows) that should be left intact during the subperiosteal medial rim dissection. The dissection is stopped at the upper end of the nasolacrimal sac within the lacrimal fossa. The anterior branch of the medial canthal tendon is then reflected anterolaterally to elevate the lacrimal sac out of the fossa.

The posterior branch of the medial canthal tendon passes posterior to the lacrimal crest and is only rarely detached from the bone. If detached, it must be reattached before closure.

The medial orbital wall can be exposed, leaving the medial canthal tendon apparatus intact.

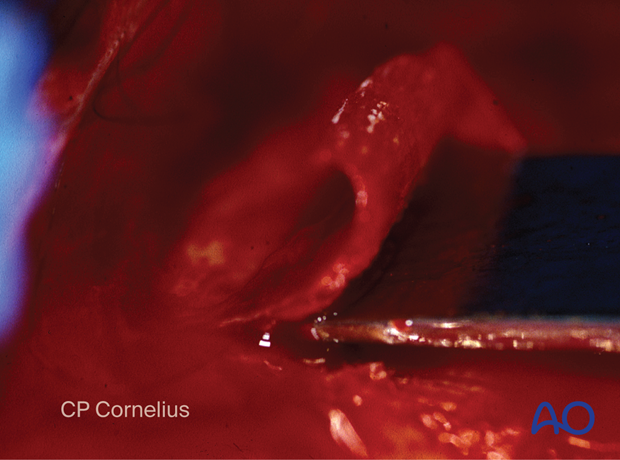

When the periorbital dissection is continued further posteriorly towards the midorbit and apex, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries are encountered along the frontoethmoidal suture.

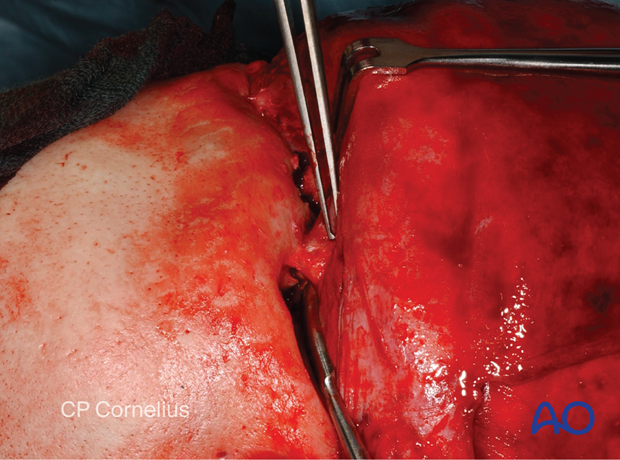

The ethmoidal arteries are covered by the periorbita, like a tent adherent to the foramina, as demonstrated in the photograph.

Bipolar cauterization and transsection of the vessels may be performed to allow extended exposure.

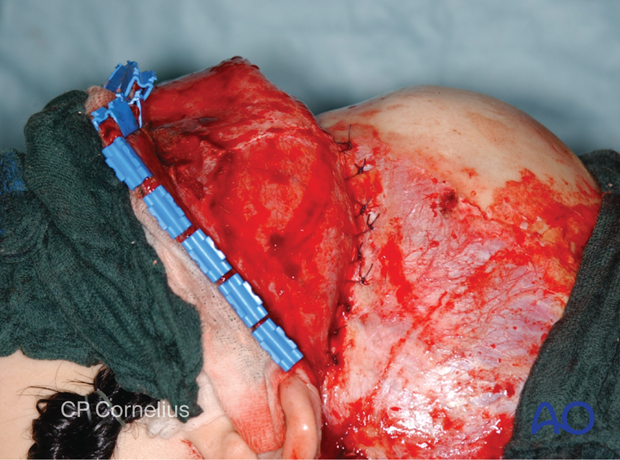

10. Exposure of the temporal fossa

If additional exposure of the external aspect of the lateral orbit and the infratemporal fossa (pterional region for transcranial access to the orbital apex) is required, the temporalis muscle is dissected from its bony attachments either limited to the anterior edge or over the entire surface of the temporal fossa.

Relaxing incisions may be placed through the temporalis fascia and the muscle substance used to develop a temporal muscle flap.

The vascular supply (deep temporal vessels) of the temporalis muscle ascends deep from the infratemporal fossa and must be preserved.

The temporal surfaces of the zygoma, the lateral orbital wall, the greater wing of the sphenoid (GWS), the temporal and frontal bones are exposed with periosteal elevators.

A 1 cm soft-tissue cuff (periosteal strip and muscle) is left below the superior temporal line to reattach the temporal muscle at the conclusion of the procedure.

11. Exposure of the temporomandibular joint and mandibular condyle/ramus

The temporomandibular joint and the upper portion of the ascending ramus of the mandible are also accessible through the extended coronal incision.

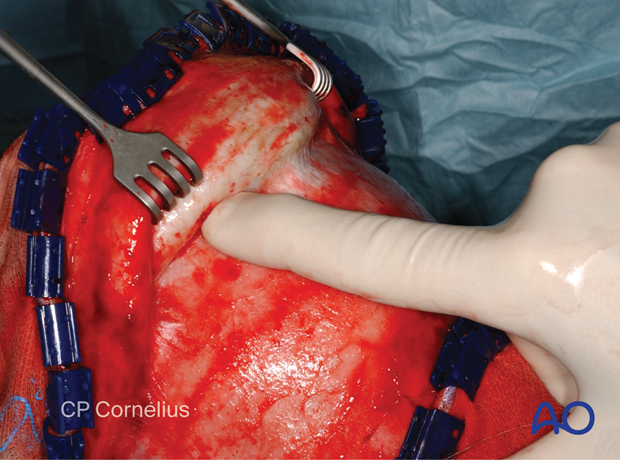

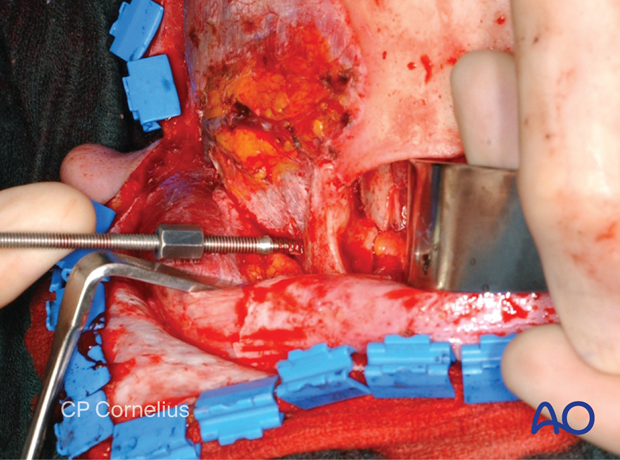

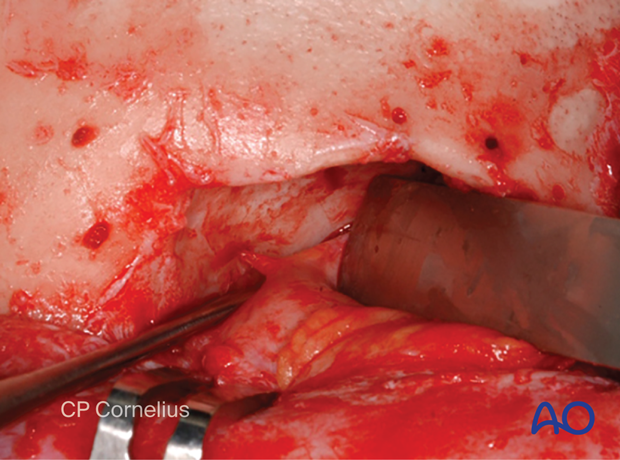

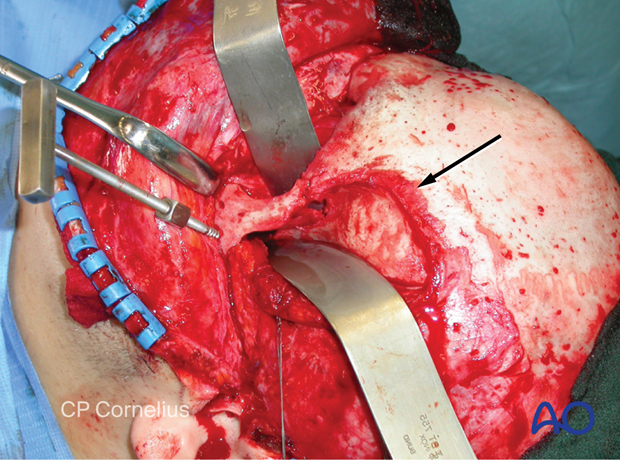

The dissection proceeds below the zygomatic arch. First, the deep part of the masseter muscle is stripped from its origin at the posterior end of the arch to expose the lateral surface of the condylar process above the joint capsule and the periosteal coverage of the condylar neck inferior to the capsular fiber insertions.

Stripping of the periosteum allows access to the anterior lateral and posterior bony surfaces of the condylar neck.

Strict subperiosteal dissection and soft-tissue retraction over the condylar neck inferiorly moves the facial nerve trunk and its branches out of the surgical field, as demonstrated.

The temporomandibular joint is not yet entered.

Access below the zygomatic arch can be extended by two methods:

- The superficial part of the masseter is released from its origin along the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch and body and then detached from the lateral surface of the ascending ramus exposing the sigmoid notch and the coronoid.

- A more elaborate technique is to perform a segmental osteotomy of the zygomatic arch. The segment is reflected laterally still pedicled to the masseter muscle, while the dissection proceeds between the bony surface of the upper ramus and the underside of the muscle.

The masseteric neurovascular bundle originating from the maxillary artery, and the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, respectively, emerge from the infratemporal fossa outward through the sigmoid notch and will be disrupted.

12. Harvesting cranial bone grafts

The cranial vault offers a large stock for harvesting calvarial bone grafts.

Depending on the type and size of the defect to be repaired, various harvesting techniques can be used:

- If a horizontal incision through the pericranium has been chosen as a route to the orbits and midface, a second incision must be made posteriorly to gain exposure to the parietal donor site area (see illustration).

- If the pericranium has already been elevated anteriorly, the dorsal wound edges may be reflected posteriorly for additional exposure of the donor site (parietal bone).

The parietal bone is the most appropriate source for cranial bone grafts. The inner and the outer cortex is thick with a wide diploë in between.

The harvesting site should be away from the cranial suture lines, particularly at the midline, to prevent injury to the sagittal sinus.

Several types of calvarial bone grafts may be taken.

Shaved corticocancellous outer table graft with attached pericranium

These small grafts are taken with a sharp osteotome after scoring their outlines with a side-cutting burr or by direct tangential cutting off a bone convexity with a reciprocating or oscillating saw. The resulting bone chips are held together by the pericranium left on the surface. The thin grafts will bend and are malleable within certain limits.

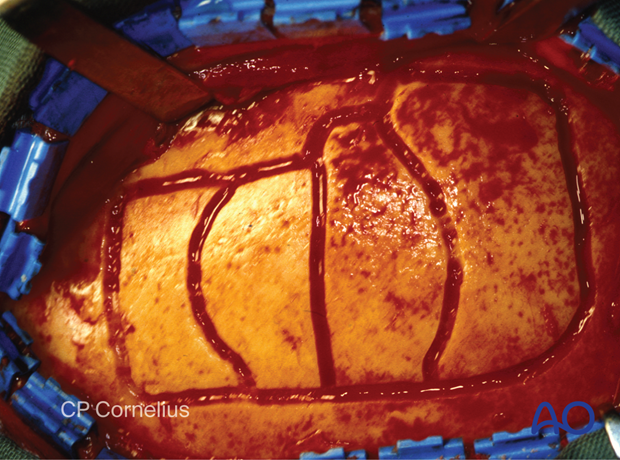

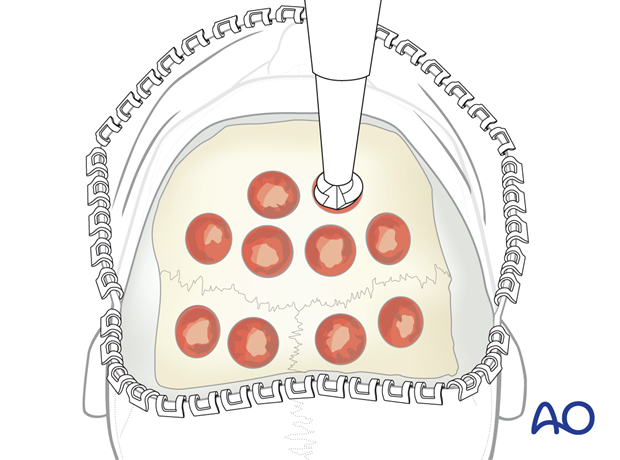

The clinical photograph shows harvesting cranial bone grafts.

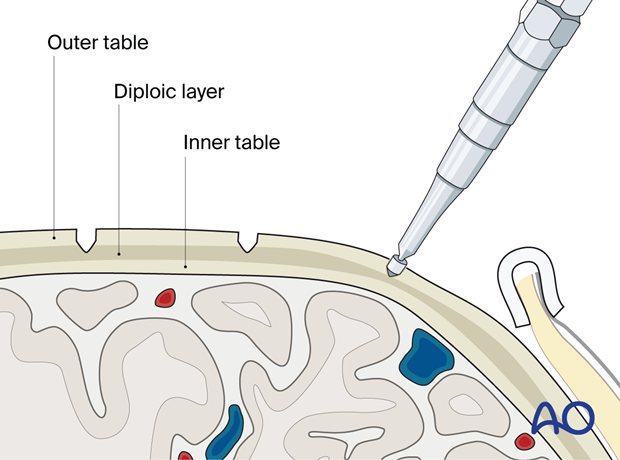

In situ split outer table grafts

For such grafts, the outer table is split from the inner table at the level of the diploic layer.

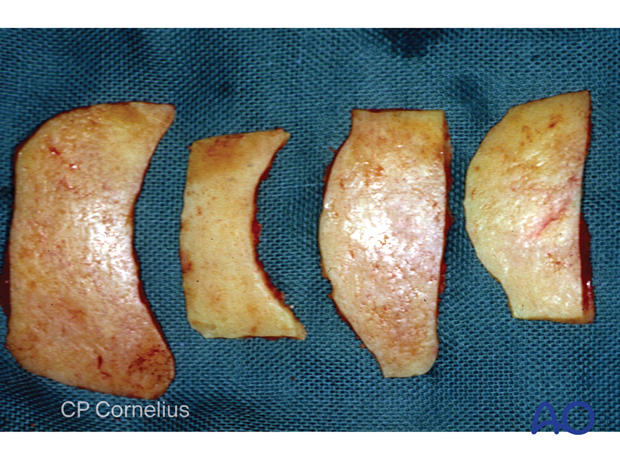

The grafts are taken in strips, either single or multiple.

The segments can be oriented either in a sagittal or transverse direction.

The outline of the grafts is traced with a side-cutting burr or a saw.

The initial grooves are deepened to the level of the diploë.

Cancellous bone bleeding indicates that the proper depth has been achieved.

A beveled trough is created along the edges of the bone graft using tangential saw cuts. This will allow for the placement of a curved osteotome to complete the harvest the outer table split calvarial bone graft.

Depending on what is required, the outer table grafts are sized to a width of up to 20 mm and may be slightly curved.

Full thickness parietal bone grafts

These grafts are removed with a formal craniotomy and are indicated if bigger bone struts or a special curvature is required.

Burr holes are made with a trephine followed by dural dissection and craniotomies.

The harvested bicortical parietal bone can be split into two laminae: The inner table is used for facial reconstruction, while the outer table is returned to cover the donor site.

Dural suspension at the edges of the craniotomy may be performed.

Instead of replanting the outer cortex, bony defects can be filled with bone graft substitutes (cranioplasty) and/or covered with titanium mesh.

Bone paste or bone dust

Bone paste or bone dust may be harvested with a hand-powered instrument or a large neurosurgical perforator at very low speed passing through the outer table into the diploic space.

Additional cancellous bone can be harvested from the diploic space using bone curettes or bone gouges.

13. Closure

Closure of the calvarial bone graft donor site precedes the facial soft-tissue resuspension and galea and scalp closure at the end of the skeletal reconstruction.

The donor site is covered with hemostatic material if necessary.

If available, the pericranium is sutured over the donor site.

Resuspension of the facial envelope

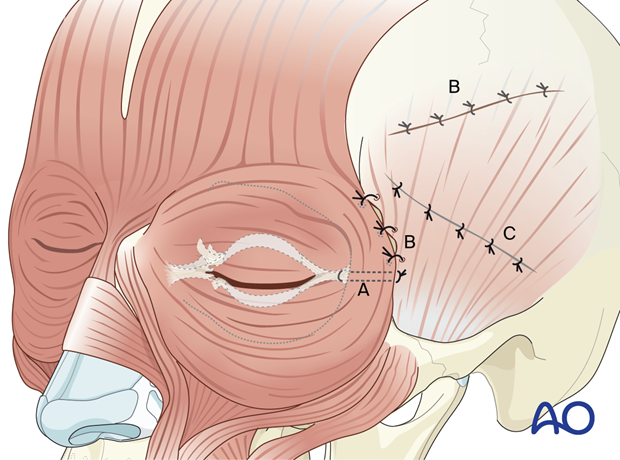

Several resuspension measures are recommended to prevent ptotic soft-tissue deformities resulting from degloving and restore the facial ligaments and septa before skin closure. The resuspension resembles a subperiosteal facelift procedure and is done in the following order (according to what is individually applicable):

- Lateral canthopexy (A)

- Resuspension of the temporal muscle (B)

- Resuspension of the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia (C)

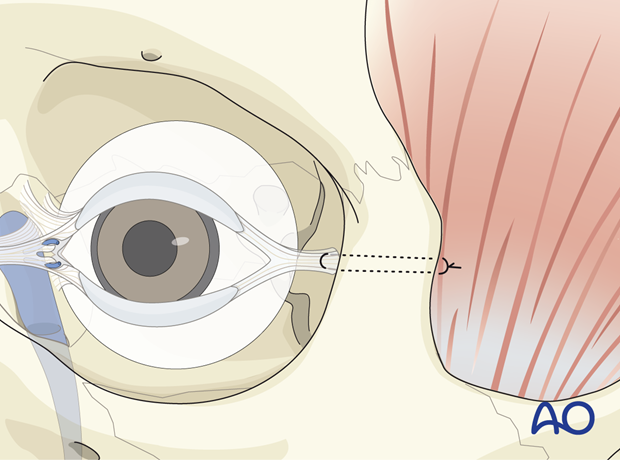

Lateral canthopexy

If the lateral canthal attachments to Whitnall’s tubercle have been detached, re-anchoring the bone is advisable.

The lateral canthus should be reattached inside the orbit and not to the rim. A secure reattachment of the canthal tendon to the bone can be achieved by drilling a hole through the lateral orbital rim.

The lateral canthus in Caucasians is usually slightly higher than the medial canthus.

The vertical and sagittal positioning of the drill hole inside the orbital wall is determined by identifying Whitnall’s tubercle.

The drill hole can be enlarged in an upward or downward direction for final adjustments.

A double-armed suture is passed through the lateral canthal tendon and passed through the hole in the lateral orbital wall. It is then passed through the temporalis fascia and secured.

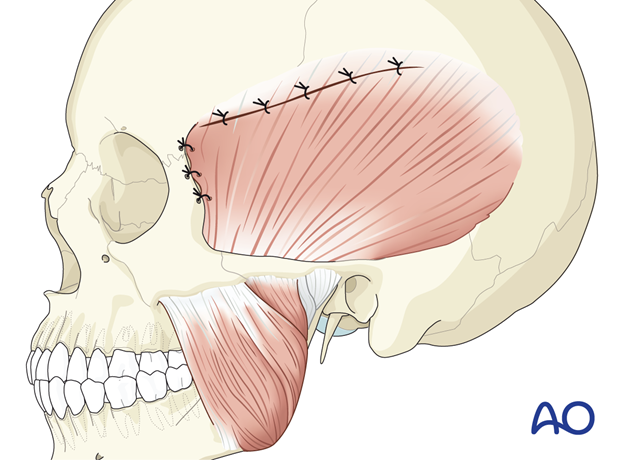

Resuspension of the temporalis muscle

Whenever the temporalis muscle has been elevated from the temporal surface of the orbit, it should also be resutured to the soft-tissue cuff left along the superior temporal line.

Moreover, suspension of the anterior muscle to the temporal edge of the lateral orbital rim is performed by passing sutures through drill holes.

Resuspension of the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia

The inferior edge of the incised superficial layer of the temporalis fascia is resuspended superiorly to the temporalis fascia with a slow absorbing running suture. An attempt is made to oversuspend the fascia to elevate the detached periosteum into its proper position on the skull.

Skin closure

The use of a suction drain is advised. Flat drains are brought out through the scalp posterior to the coronal incision.

Finally, the scalp is folded back and adequately aligned into the original position.

The wet gauze and the hemostatic clips are removed stepwise, and hemostasis is achieved. The scalp is then closed in two layers along the exposed wound edges.

For the galea/subcutaneous layer, slow resorbing 2-0 sutures are used. The skin incision is closed with permanent skin sutures or surgical staples. Staples are preferred if the hair was not shaved.

The preauricular extension of the coronal incision is closed in layers.

Hair and skin are copiously rinsed to remove residual blood clots.

A compressive head dressing may be placed to prevent hematoma formation underneath the coronal flap. It should not be too tight, as periorbital edema will intensify with the scalp under tight pressure.

The scalp skin sutures/staples are removed ten days postoperatively. Preauricular skin sutures are removed after six days.