Operative treatment

1. Introduction

Before proceeding with definitive repairs, the patient must be fully resuscitated, fully evaluated, and fit for anesthesia and surgery by a prepared team.

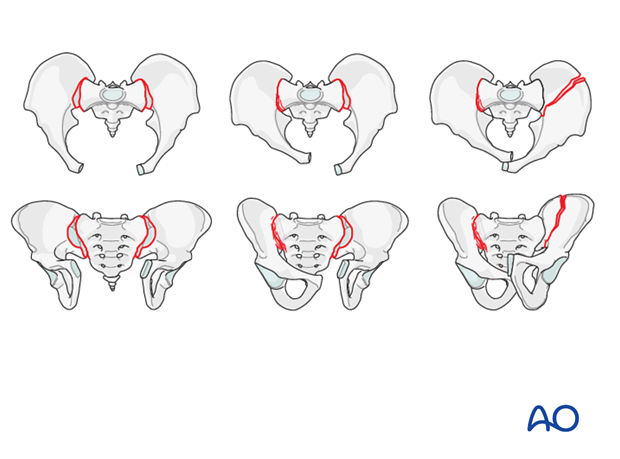

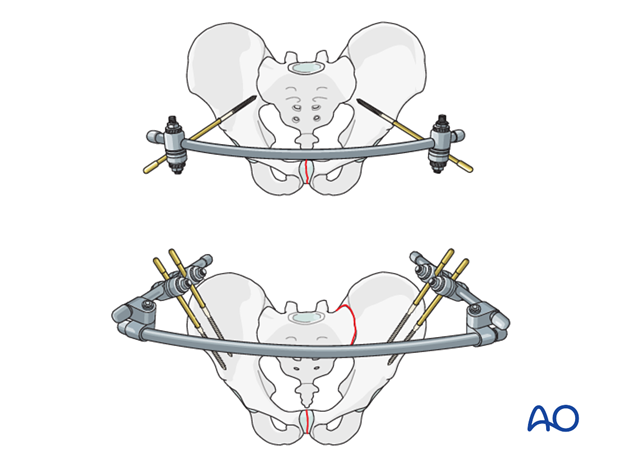

If displacement occurs bilaterally, deformity of the entire pelvic ring can be significant. The three possible deformities are:

- Both sides externally rotated

- One side internally the other externally rotated

- Both sides internally rotated

With mobility and displacement of both hemipelves, reapproximation of each injury does not by itself guarantee correct alignment. Malreduction with excessive or insufficient rotation of the posterior injuries is possible, resulting in pelvic ring asymmetry. This can be recognized by displacement of the pubic symphysis away from the midline.

The goals of treatment are to restore:

- anatomical alignment of the pelvis, including normal shape and symmetry

- sufficient stability for patient mobility

Emergency care for pelvic ring injuries should be available and preplanned at every trauma hospital. Patients with complex pelvic ring injuries may need to be referred to a specialized center.

Lumbo-sacral nerve root injury

Before undertaking definitive treatment of pelvic ring injuries, It is essential to know the functional status of the patient's lumbosacral nerve roots. A careful and detailed examination is necessary, to assess perineal sensation, voluntary anal sphincter contraction, and bulbo-cavernosus reflex. Cystometrography may be helpful to assess bladder neuromotor function.

Neurologic abnormalities should be correlated with anatomic site of injury:

- If a lumbo-sacral nerve deficit is present in extra sacral injuries, further investigation and possible treatment must be considered.

- If a sacral nerve deficit is present with a sacral fracture, the nerves should be decompressed with fracture reduction and/or sacral laminectomy.

Pelvic ring stability

The definition these injuries requires that both posterior injuries exhibit only rotational (partial) instability. This implies that a posterior hinge is present bilaterally.

However, the actual strength of the remaining posterior arch tissue ("hinge") is not easily assessed. Rotational stability, in the sense that anterior repair alone is sufficient, cannot be safely relied upon. Both anterior and bilateral posterior fixation is therefore recommended.

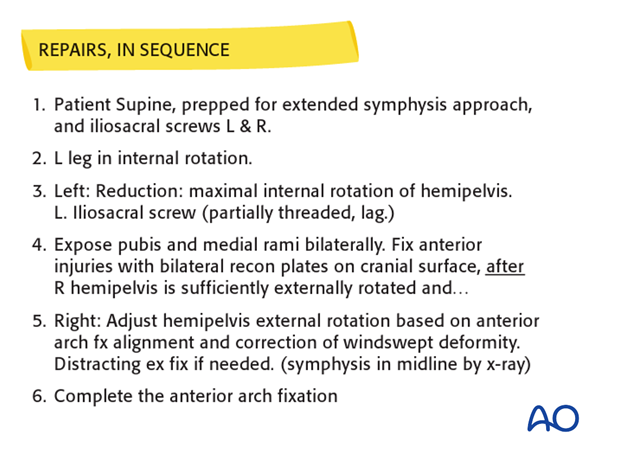

2. Sequence of reduction and fixation

Reduction and fixation of the anterior arch are usually performed first, especially if the pubic symphysis is disrupted. This should improve posterior arch alignment, but ring alignment is not necessarily corrected.

When a posterior injury can readily be reduced and fixed in anatomical alignment, this may be performed as a first step. This will provide a stable well-aligned hemipelvis upon which the rest of the reconstruction can be based.

Provisional internal or external fixation can be used to progressively stabilize the pelvis during reconstruction. This should allow for adjustments as necessary to reduce additional sites of displacement.

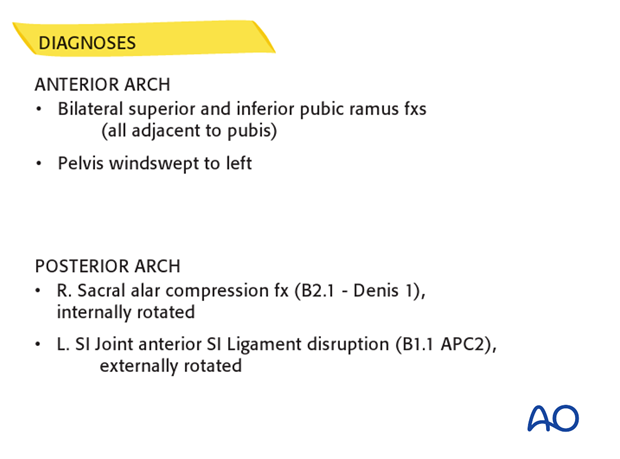

3. Preoperative planning

An explicit, written pre-operative plan is strongly encouraged. The following provides an outline of recommended steps.

Assess and consider:

- Whole patient (physiologic status and other injuries)

- Pelvic region & organ systems (local details of pelvic region including soft tissues and related organ system injuries)

- X-rays and CT scans (reviewed in detail for patients individual anatomy, each injury, and overall pelvic configuration)

Identify and list each individual pelvic ring injury.

For each injury, determine displacement, stability, and a strategy for reduction and fixation (relevant techniques are outlined and discussed below).

List, in order, each step of your planned procedure

Finally review the step-by-step list to:

- Confirm plan

- List equipment and implants

- Consider potential problems and solutions

- Share the plan with other members of the operative team – including nursing staff, radiographic technician, and anesthesia staff.

4. Patient preparation

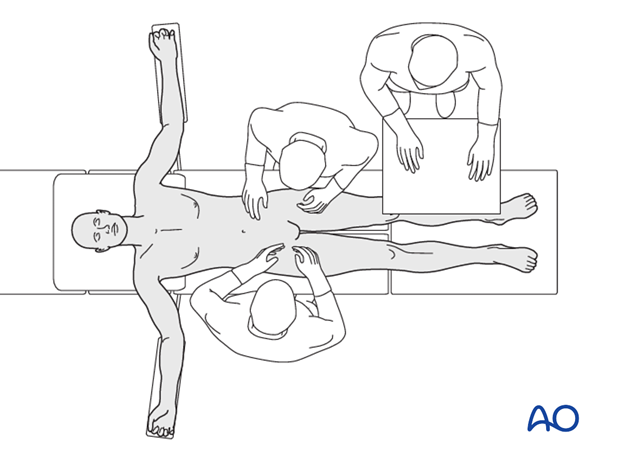

This procedure is performed with the patient in a supine position.

5. Approaches

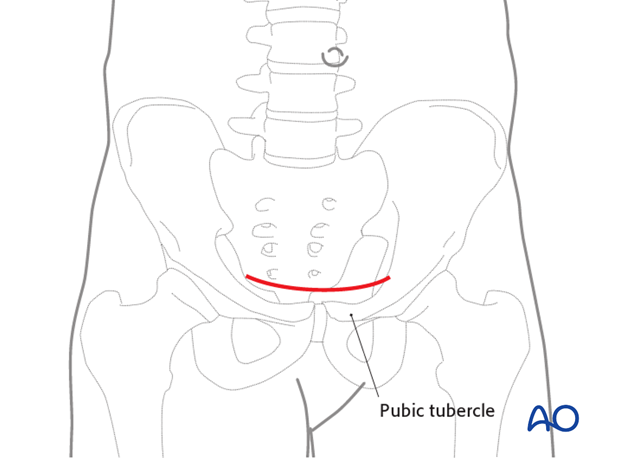

The standard approach to the symphysis is used for its reduction and fixation.

For more lateral exposure of the pubic ramus, a lateral extension of the standard approach or a modified Stoppa approach may be necessary.

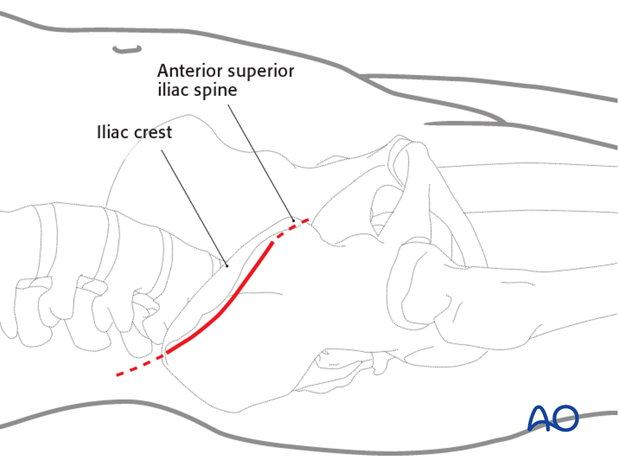

For access to an unstable iliac fracture or SI joint, the anterior approach to the iliac wing is necessary.

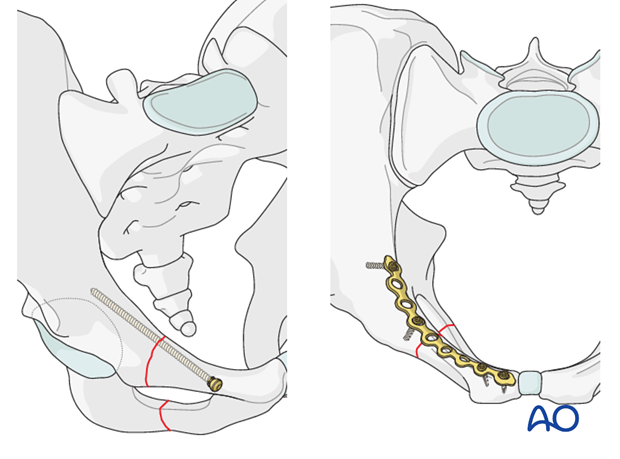

Special consideration must be given to crescent fractures, for which fixation depends upon the fracture anatomy, leading to possible anterior or posterior ORIF, or percutaneous iliosacral screw fixation.

Pubic ramus intramedullary screws are inserted through stab wounds, either over the pubic tubercle (for retrograde insertion) or laterally over the acetabulum (for antegrade insertion).

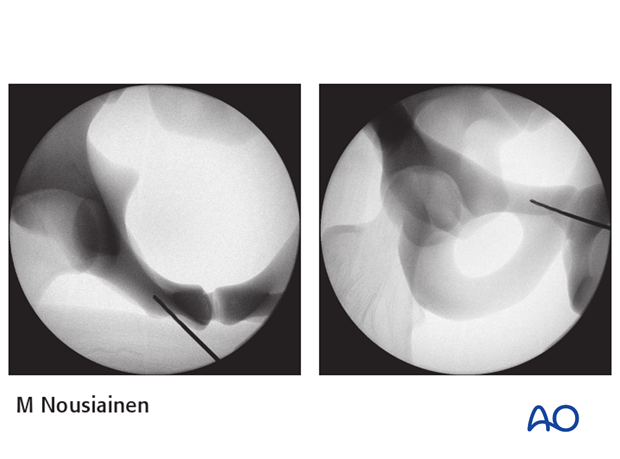

The location of the stab wound is found using a C-arm and a K-wire.

For retrograde screw insertion, the surgeon stands on the opposite side of the table from the ramus being fixed.

6. Reduction and fixation

Anterior fixation

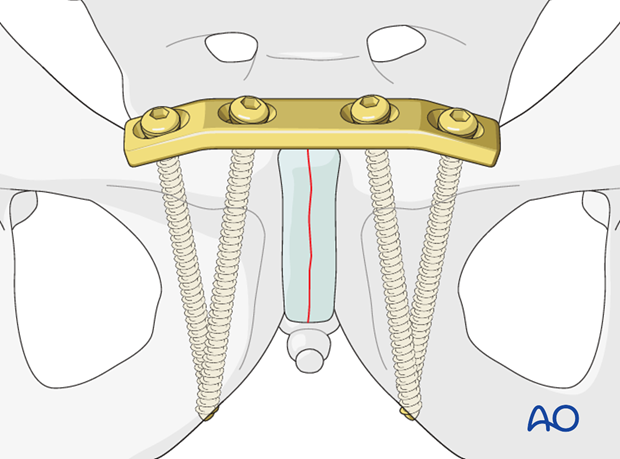

Choice of anterior fixation is based upon the individual anterior arch injuries.

Several different techniques of anterior arch fixation are available. Clear indications for one over the other are rarely present.

If a satisfactory reduction of the pubic ramus cannot be obtained closed, open reduction is indicated either with an anterior approach to the symphysis (medial fractures) or a modified Stoppa approach (lateral fractures, or posterior plating). With open reduction, fixation can be performed with either a pubic ramus IM screw or plate.

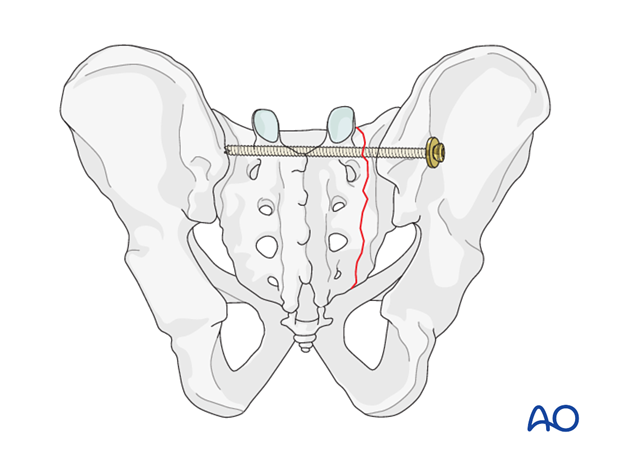

If an external fixator is used for reduction, it is often sufficient for stabilization while a well aligned ramus fracture heals. This may be preferred to avoid an extensive exposure when a complex comminuted ramus fracture is present yet satisfactory aligned.

The pubic symphysis plating is indicated for symphyseal disruption and/or pubic body fractures. For this procedure the anterior approach to the symphysis may be used.

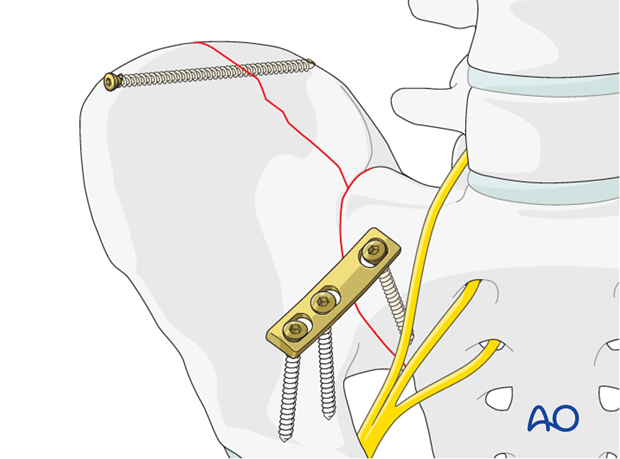

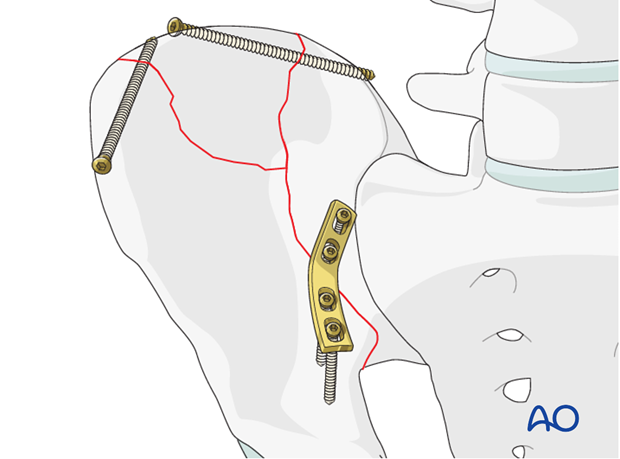

Posterior fixation

Posterior fixation may be advisable for one or both of the posterior arch injuries.

Percutaneous iliosacral screw fixation is usually the preferred technique.

In the rare case of a sacral fracture, this should be repaired with an IS Screw, unless it is displaced or associated with neurological deficit.

If available, the use of intraoperative navigation may be beneficial for iliosacral screw fixation.

Larger crescent fractures can be repaired through an anterior (preferred) or posterior approach.

In the exceptional case of an unstable iliac fracture, this should be plated through the anterior approach to the iliac wing.

7. Check of osteosynthesis

Check the completed osteosynthesis with Imaging, and physical exam if there is any question about pelvic stability.

Using inlet and outlet views, with the C-arm, confirm that pelvic deformity has been corrected and that involved sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis are anatomically reduced.

Unless a C-arm with a large field of view is available, it may be wise to obtain similarly oriented portable x-rays of the entire pelvis, to be certain about overall alignment.

Confirm that reduction of each fracture or joint injury is satisfactory, Make sure that all fixation devices are properly placed, and that each screw is of appropriate length. Multiple views are typically needed, including both axial and perpendicular views for questionable screws. If screws protrude from bone, consider risks to nerves, vessels, and adjacent viscera, especially urethra and bladder after pubic symphysis repair.

8. Aftercare following open reduction and fixation

Postoperative blood test

After pelvic surgery, routine hemoglobin and electrolyte check out should be performed the first day after surgery and corrected if necessary.

Bowel function and food

After extensile approaches in the anterior pelvis, the bowel function may be temporarily compromised. This temporary paralytic ileus generally does not need specific treatment beyond withholding food and drink until bowel function recovers.

Analgesics

Adequate analgesia is important. Non pharmacologic pain management should be considered as well (eg. local cooling and psychological support).

Anticoagulation

Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus is routine unless contraindicated. The optimal duration of DVT prophylaxis in this setting remains unproven, but in general it should be continued until the patient can actively walk (typically 4-6 weeks).

Drains

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Wound dressing

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Physiotherapy

The following guidelines regarding physiotherapy must be adapted to the individual patient and injury.

It is important that the surgeon decide how much mechanical loading is appropriate for each patient's pelvic ring fixation. This must be communicated to physical therapy and nursing staff.

For all patients, proper respiratory physiotherapy can help to prevent pulmonary complications and is highly recommended.

Upper extremity and bed mobility exercises should begin as soon as possible, with protection against pelvic loading as necessary.

Mobilization can usually begin the day after surgery unless significant instability is present.

Generally, the patient can start to sit the first day after surgery and begin passive and active assisted exercises.

For unilateral injuries, gait training with a walking frame or crutches can begin as soon as the patient is able to stand with limited weight bearing on the unstable side.

In unstable unilateral pelvic injuries, weight bearing on the injured side should be limited to "touch down" (weight of leg). Assistance with leg lifting in transfers may be necessary.

Progressive weight bearing can begin according to anticipated healing. Significant weight bearing is usually possible by 6 week but use of crutches may need to be continued for three months. It should remembered that pelvic fractures usually heal within 6-8 weeks, but that primarily ligamentous injuries may need longer protection (3-4 months).

Fracture healing and pelvic alignment are monitored by regular X-rays every 4-6 weeks until healing is complete.

Bilateral unstable pelvic fractures

Extra precautions are necessary for patients with bilaterally unstable pelvic fractures. Physiotherapy of the torso and upper extremity should begin as soon as possible. This enables these patients to become independent in transfer from bed to chair. For the first few weeks, wheelchair ambulation may be necessary. After 3-4 weeks walking exercises in a swimming pool are started.

After 6 weeks, if pain allows, the patient can start walking with a three point gait, with less weight bearing on the more unstable side.

Full weight bearing is possible after complete healing of the bony or ligamentous legions, typically not before 12 weeks.