ORIF - Compression plating

1. General considerations

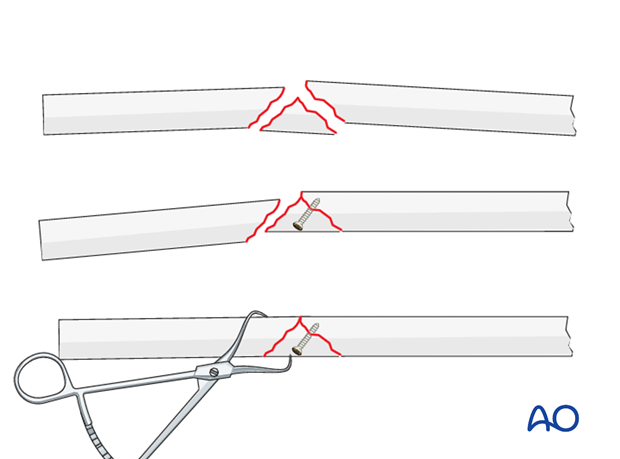

In the past, wedge fractures have usually been fixed rigidly. The underlying principle focused on mechanical issues, not on biology. Today, biology takes precedence and for this reason not all wedge fragments are incorporated rigidly into the fixation.

Small wedge fragments that do not have a significant effect on stability should not be addressed (they will become incorporated into the fracture by indirect bone healing). Larger wedge fragments that contribute to the stability of the fixation, are fixed to one main fragment. Sometimes, fixation of the wedge to one main fragment helps reduction of the residual fracture.

If a lag screw is inserted separate from the plate, a 2.7 mm screw is often used, depending on the size of the bone, for biological reasons, and to reduce the risk of splitting the wedge.

If a lag screw is inserted through a 3.5 mm plate, a 3.5 mm screw should be used.

Note on approaches

When both bones need to be reduced and fixed, a separate approach to each bone should be performed to reduce the risk of heterotopic bone formation.

For proximal radial shaft fractures, the anterior approach (Henry) is most often used to minimize the risk of damage to the posterior interosseous nerve, which crosses the proximal radius within the supinator muscle.

In mid and distal radial shaft fractures, either the anterior approach (Henry) or posterolateral approach (Thompson) can be used, depending on surgeon’s preference.

The ulna is exposed by the standard subcutaneous approach between the flexor and extensor muscle compartments.

2. Principles

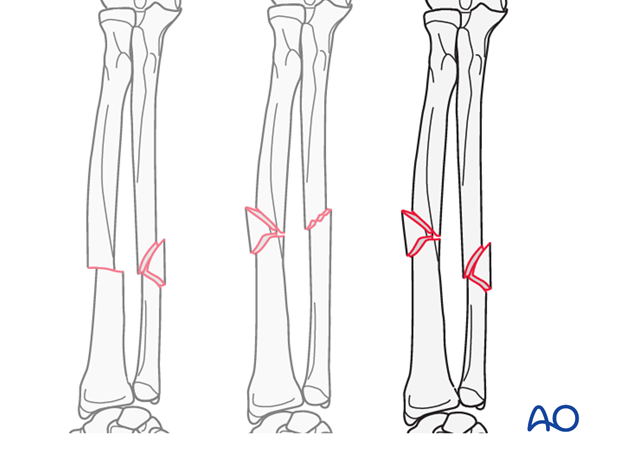

Order of fixation

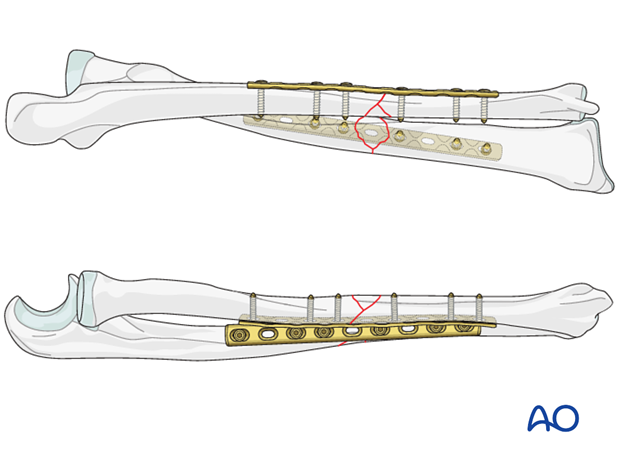

Normally, the simpler of the two fractures will be approached first and preliminary fixation undertaken. If both bones have similar fractures, then the ulna will normally be addressed first.

Most often, fixation of fractures involving both bones proceeds as follows:

- Reduction and preliminary fixation of the simpler fracture. In the case of wedge fractures of both bones start with the bone with the smaller wedge

- Reduction and definitive fixation of the other bone

- Definitive fixation of the first bone

Never commit yourself to the definitive fixation of one bone until you have assured yourself that you can reduce the other bone.

If a reduction of the second bone is impossible, the preliminary fixation of the first bone must be loosened and the other bone reduced and fixed. The first bone is then restabilized.

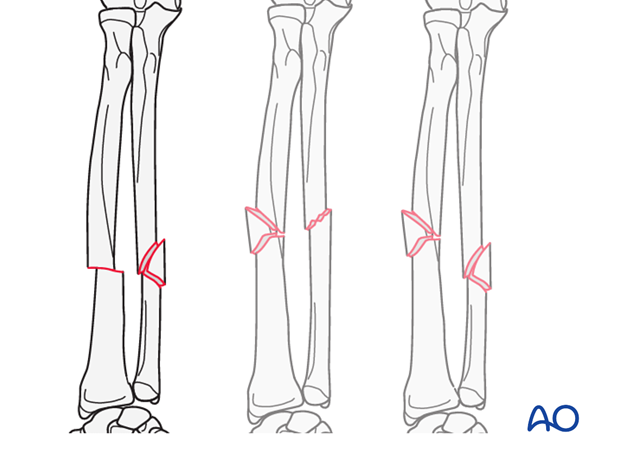

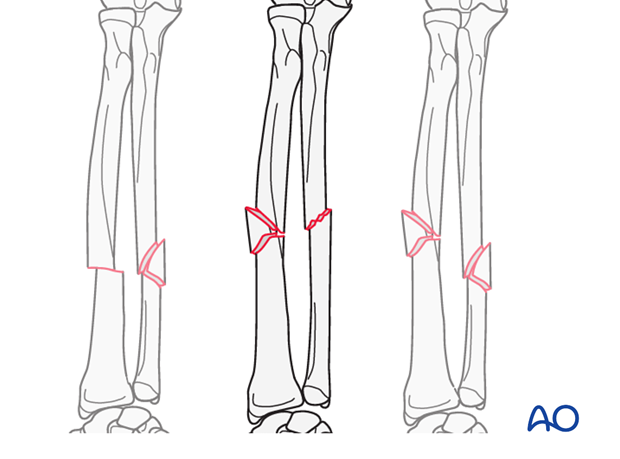

This illustration shows a simple ulnar fracture, radial wedge fracture in which preliminary fixation of the simple ulnar fracture would be the first step.

Throughout this module, the fixation of each bone will be described to completion, but the surgeon is reminded not to complete the first fixation until the second bone has been definitively fixed.

3. Patient preparation

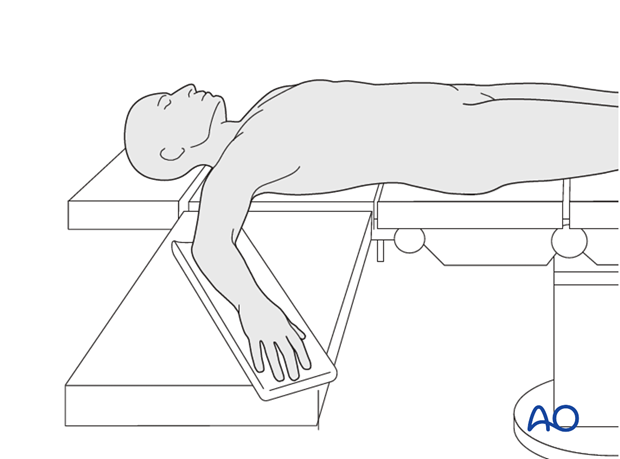

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

4. Detailed procedures

Ulnar wedge and radial simple fracture

Required steps are:

- Preliminary fixation of oblique radial fracture, or preliminary fixation of transverse radial fracture

- Definitive fixation of the ulnar wedge fracture

- Completion of radial fixation and check of osteosynthesis

The required techniques are:

Ulnar simple and radial wedge fracture

Required steps are:

- Preliminary fixation of oblique ulnar fracture, or preliminary fixation of transverse ulnar fracture

- Definitive fixation of the radial wedge fracture

- Completion of ulnar fixation and check of osteosynthesis

The required techniques are:

Wedge fracture of both bones

Required steps are:

- Preliminary fixation of the ulnar wedge fracture

- Definitive fixation of the radial wedge fracture

- Completion of fixation of ulnar wedge fracture and check of osteosynthesis

The required techniques are:

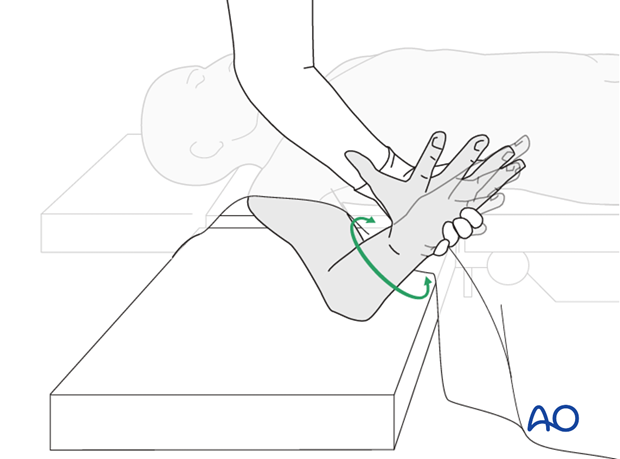

5. Check of osteosynthesis

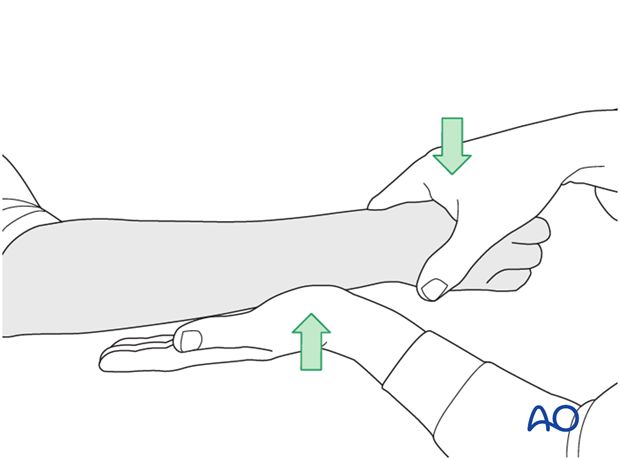

Check the completed osteosynthesis by image intensification. Make sure that the plate(s) are at proper locations, the screws are of appropriate length and a proper reduction was achieved.

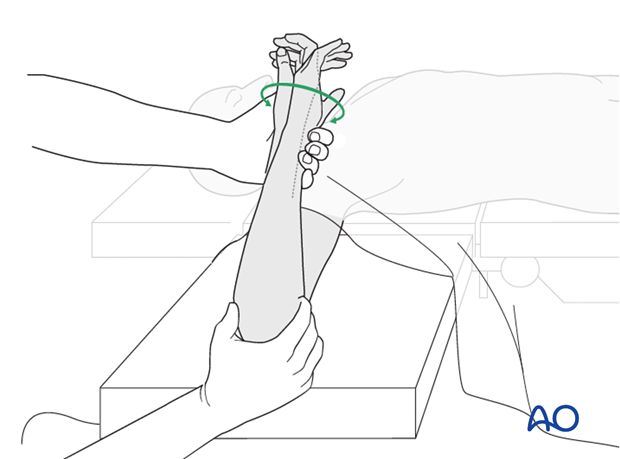

The elbow should be stabilized at the epicondyles and the forearm rotation should be checked between the radial and ulnar styloids.

6. Assessment of Distal Radioulnar Joint (DRUJ)

Before starting the operation the uninjured side should be tested as a reference for the injured side.

After fixation, the distal radioulnar joint should be assessed for forearm rotation, as well as for stability. The forearm should be rotated completely to make certain there is no anatomical block.

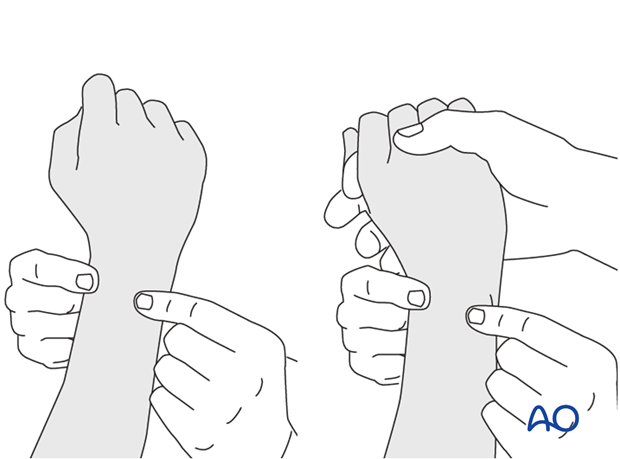

Method 1

The elbow is flexed 90° on the arm table and displacement in dorsal palmar direction is tested in a neutral rotation of the forearm with the wrist in neutral position.

This is repeated with the wrist in radial deviation, which stabilizes the DRUJ, if the ulnar collateral complex (TFCC) is not disrupted.

This is repeated with the wrist in full supination and full pronation.

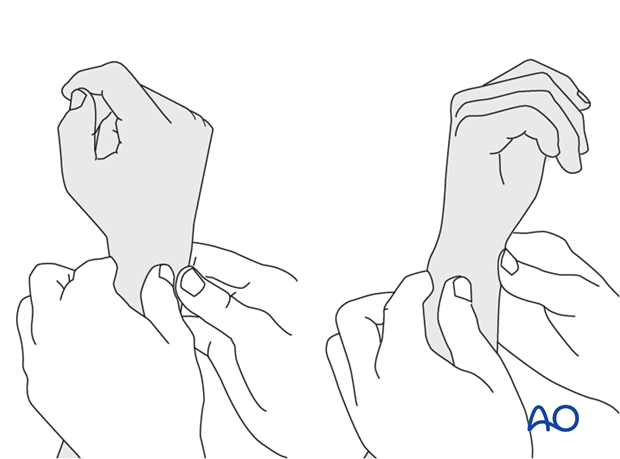

Method 2

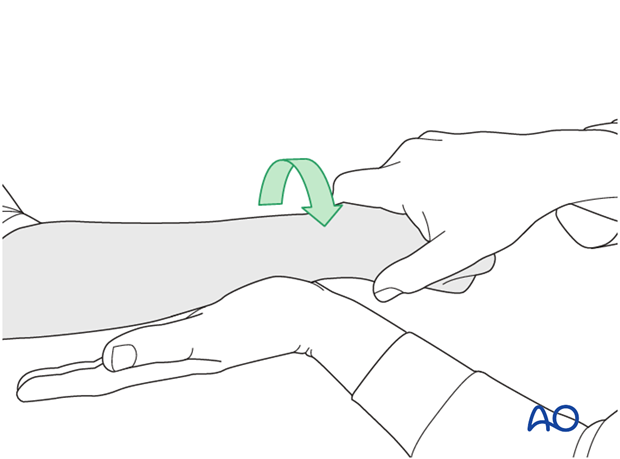

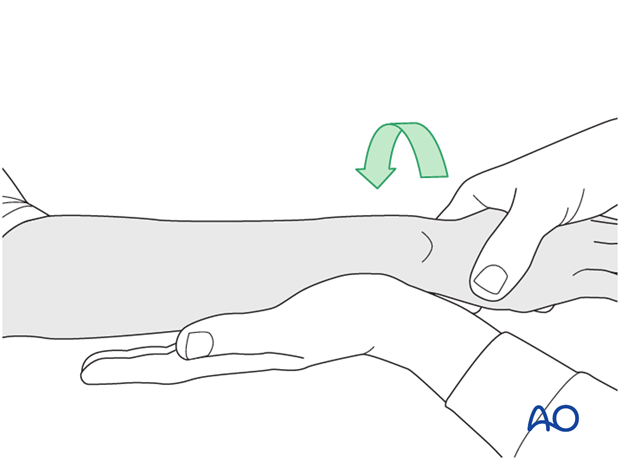

In order to test the stability of the distal radioulnar joint, the ulna is compressed against the radius...

...while the forearm is passively put through full supination...

...and pronation.

If there is a palpable “clunk”, then instability of the distal radioulnar joint should be considered. This would be an indication for internal fixation of an ulnar styloid fracture at its base. If the fracture is at the tip of the ulnar styloid consider TFCC stabilization.

7. Postoperative treatment of a fracture treated with plating

Functional aftercare

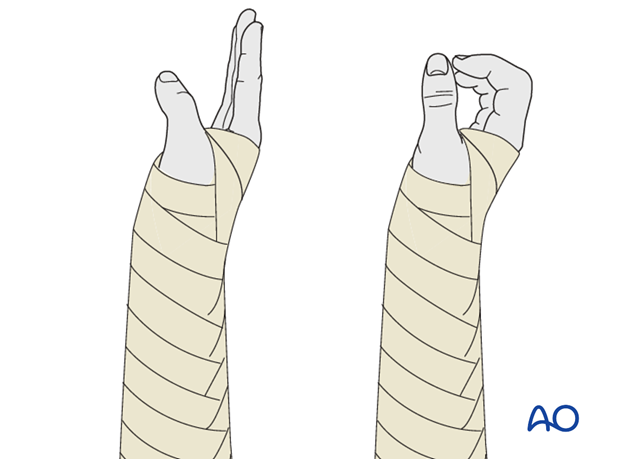

Following stable fixation, postoperative treatment is usually functional.

Immobilization in a circular cast may compromise the range of motion later. Temporary immobilization with a well-padded, bulky splint for 10-14 days is advised to allow adequate soft-tissue healing. During this period, elevation, gentle finger motion, active and passive, together with elbow flexion/extension and shoulder motion, can be started. The splint is then removed and active assisted range of motion exercises, including gentle forearm rotation, begin.

Lifting and resisted exercises are restricted until radiographic signs of healing appear. More intensive exercises, such as progressive resisted exercises can start thereafter. Timing of return to sport will depend on the individual patient and the nature of the sport.

Follow-up

Close postoperative follow-up is required in fractures that have been treated by means of absolute stability. Direct bone healing without callus formation is anticipated and early signs of instability with the presence of irritation callus should alert the surgeon to consider secondary interventions, such as restabilization and bone grafting.

Follow-up x-rays should be obtained according to local protocol. X-rays to assess fracture position are usually taken at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after operation. Subsequent x-rays are usually taken to assess bony healing at appropriate intervals from 6-8 weeks, depending on the fracture configuration and potential for healing.

Implant removal

In forearm shaft fractures, the issue of implant removal is controversial. As the radius and ulna are not weightbearing bones, and as removal of plates can be a demanding procedure, implant removal is not indicated as a routine. There is a high risk of nerve damage associated with procedures to remove forearm plates.

Furthermore, as there is significant risk of refracture, most surgeons prefer not to remove plates from the forearm.

The general guidelines today are:

- removal only in symptomatic patients, possibly only on the ulna where the implants are subcutaneous

- removal no earlier than 2 years after osteosynthesis

- If both bones have been plated, sequential removal of implants with a least 6 months in between is recommended (risk of refracture).

References

- Bednar DA, Grandwilewski W (1992) Complications of forearm-plate removal. Can J Surg; 35(4):428-431.

- Langkamer VG, Ackroyd CE (1990) Removal of forearm plates. A review of the complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br; 72(4):601-604.

- Rosson JW, Shearer JR (1991) Refracture after the removal of plates from the forearm. An avoidable complication. J Bone Joint Surg; 73(3): 415-417.

- Heim D, Capo JT (2007) Forearm, shaft. Rüedi TP, Buckley RE, Moran CG (eds), AO Principles of Fracture Management, Vol. 2. Stuttgart New York: Thieme-Verlag, 643-656.