ORIF - Plate and screws

1. Single-stage or multiple-stage surgery?

Principles

Total articular fractures require anatomical reduction and stable fixation of the articular surface. Usually, this requires direct reduction of the joint fragments, but indirect reduction and less invasive fixation may be more appropriate for the metaphyseal region. Totally minimally invasive fixation may rarely be indicated when the joint surface fracture is nondisplaced, and perhaps very simple fractures that can be reduced percutaneously and assessed completely reliably with x-ray control.

Most simple total articular fractures are more accurately reduced through a limited open surgical approach. This involves direct exposure of the joint and minimal extension proximally for plate insertion.

The soft-tissue conditions usually dictate the choice of procedure: early single-stage or multiple-stage surgery.

Displaced fractures with minimal closed soft-tissue injury

(Tscherne classification, closed fracture grade 0, rarely grade 1)

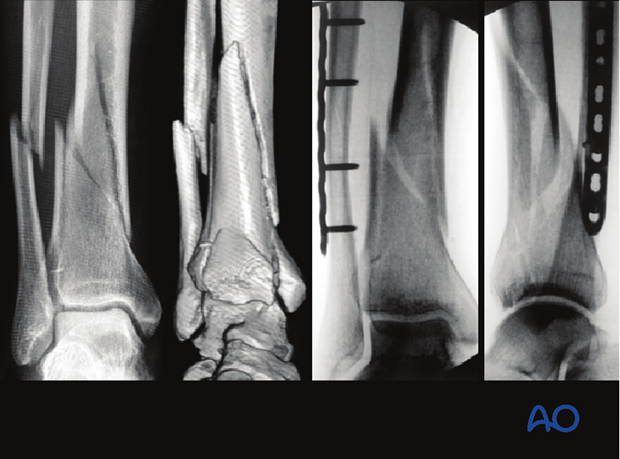

Reconstruction may be done with a single-stage procedure, like the proposals of Rüedi and Allgöwer. This involves complete restoration of the ankle mortise including fibula and tibia. This may require bone grafting and usually a buttress plate. The goal is absolute stability of the joint surface, to permit early motion and achieve healing with anatomical alignment. Assuming a truly minimal soft-tissue injury, the complete reconstruction can be done as soon as preparations are complete.

Grossly displaced fractures and / or fractures with moderate to severe closed soft-tissue injury

(Tscherne classification, closed fracture grade 2 or 3)

It is generally advisable to proceed in two or more stages:

- Closed reduction and joint bridging external fixation

- Definitive open reconstruction after 5-10 days (wait for the appearance of skin wrinkles)

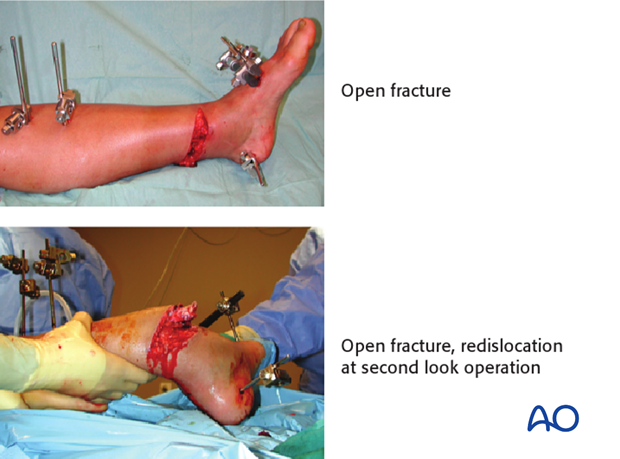

Open pilon fractures

These are very severe injuries often requiring plastic surgery for soft-tissue reconstruction. The management includes the following stages:

1. Emergency management:

- Wound debridement and lavage

- Joint-bridging external fixation

- Fibular fixation may also be considered, but rarely adds benefit and may require another incision through badly injured tissue

- Open wound management with occlusive dressing (possible antibiotic bead pouch or vacuum dressing)

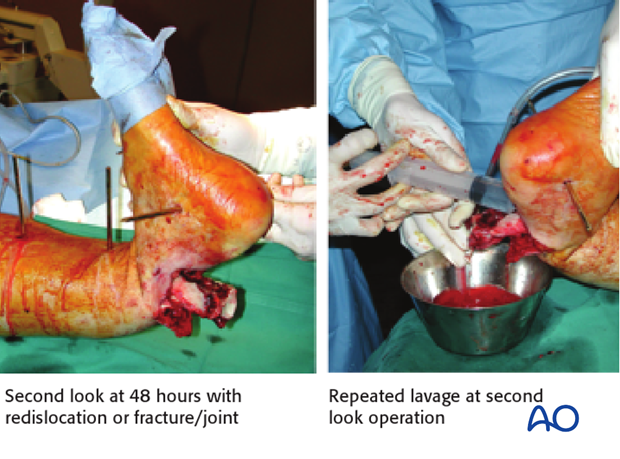

2. At 48 hours:

- Second look with repeated lavage (re-dislocation of fracture/joint!) and re-debridement if necessary

- Reconstruction of the tibial articular block

- Soft-tissue coverage (local or free flap), if possible. Significant delay of coverage increases infection risk

3. Definitive stabilization:

- Bridging of the metaphyseal comminution, with or without bone graft

- Definitive stabilization with internal or external fixation may be performed at 48 hours, or preferably later.

Image shows second look at 48 hours with redislocation of the fracture/joint and repeated lavage at second look operation.

2. Fibula or tibia first? Sequence of bone stabilization

Introduction

The ankle joint involves the tibial-fibular mortise and talus. If the fibula is not properly attached to the tibia, the joint will not be congruent. If there is a fibular fracture, it usually must be repaired. The surgeon must choose whether to do it first or later.

Simple fracture of the fibula

If the fibular fracture is simple, this fracture is fixed as a first step by open reduction and stable plate fixation. This indirectly reduces attached lateral fragments of the tibial articular surface through the usually intact syndesmotic ligaments. ORIF of the articular surface of the tibia and stable meta-diaphyseal fixation then follow.

Multifragmentary fibular fracture

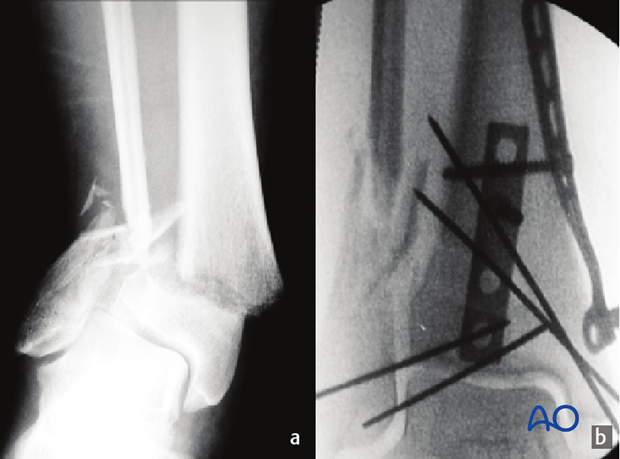

Comminuted fibular fractures (a) are difficult to reduce accurately. In such cases it is usually better to reconstruct the tibia first and use the tibia and talus as guides for positioning the lateral malleolus, if necessary. This usually reduces the fibular fracture indirectly. Since the syndesmotic ligaments are usually intact, gross realignment of the fibula often occurs as the tibia is reduced (b).

The comminuted fibular fracture can often be stabilized with a subcutaneous plate, without exposing the fragments (c) using a long bridging plate (d). It is essential to achieve correct length, rotation, and axial alignment of the fibula.

3. Preoperative planning

Preoperative planning is an essential part of the treatment of all distal tibial fractures:

- Obtain good AP and lateral x-rays of both injured and uninjured side; CT if needed

- Careful study of the x-rays and CT scan

- Trace AP and lateral x-rays of normal side

- Identify the individual fracture fragments

- Draw the fracture fragments, reduced, onto the normal tracing

- Consider reduction techniques

- Choose and draw in fixation implants

- Choice of surgical approach

- Prepare list of operative steps

Choice of the surgical approach

Depending on the location of the articular part of a simple articular fracture, an anteromedial or anterolateral approach is required. The approach may be limited, but sufficient exposure is necessary for direct articular fracture reduction. Plate insertion proximally can be minimally invasive.

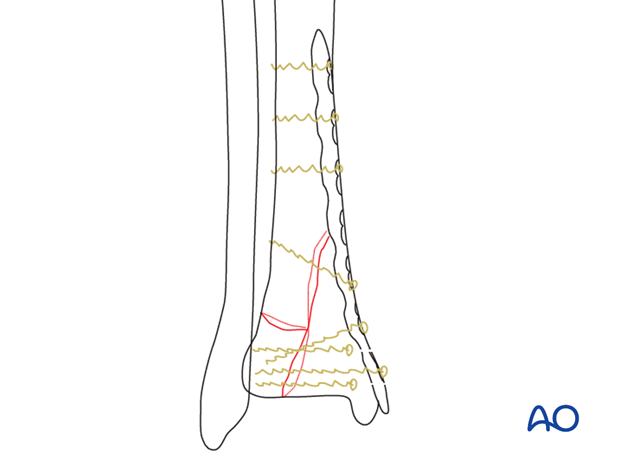

Choice of implant

Interfragmentary compression with lag screws is the basic technique for reconstruction of articular surface fractures. For completely articular fractures, a plate is usually selected to connect the joint surface to the tibial shaft. The preoperative plan should include strategically placed lag screws that do not interfere with the planned plate construct.

Additional interfragmentary lag screws can be placed through the distal holes in the plate. To make this possible, the exact position of the plate must be determined during preoperative planning. See also the additional material on lag screw principles.

The shape and location of the plate are important for metaphyseal reduction and must be planned preoperatively.

A variety of precontoured distal tibial plates are available. They usually need slight adjustment of contouring. It is important that the plate be contoured properly before insertion. Longer implants improve load distribution and stability. Only a small number of screws will be needed in the tibial shaft.

A locking or conventional plate can be used. The bone quality, fracture pattern, and length of the distal segment will be the primary determinants. The cost and availability of angular stable fixation and anatomically precontoured plates must also be considered. Well-planned use of conventional fixation remains a reasonable alternative to locking plates in most if not all situations.

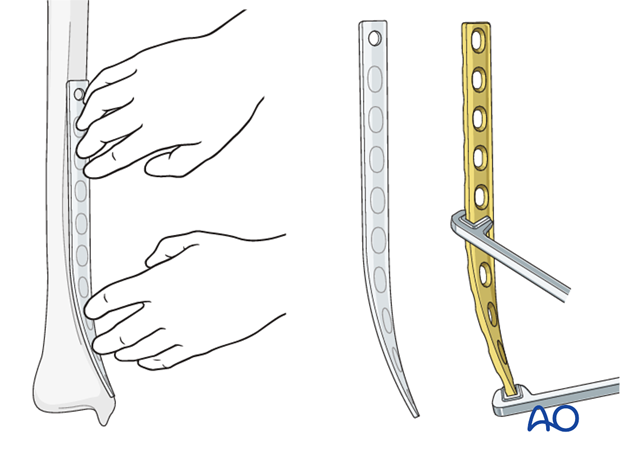

Plate contouring

If precontoured implants are not available a non-contoured plate can be shaped prior to sterilization, using a sawbones model as a template.

Determine the length of the plate from preoperative x-rays. It should be placed as distally as possible and long enough to place at least four holes proximal to the fracture (with screws in at least three of them).

The most distal 8-12 cm of the plate must be bent to form a concave arc with a radius of curvature of about 20 cm and twisted to fit the distal tibia. As illustrated, the medial tibia is internally rotated distally (20 degrees) and lies closer to the sagittal plane.

4. Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

5. Reduction and stabilization of the articular segment

The articular segment must be reduced anatomically and either provisionally or definitively stabilized. This can be accomplished with a pointed reduction clamp, K-wires, independent lag screws, or combinations thereof. In the illustration, the articular segment is reduced through a limited anteromedial incision which is also used to place two 3.5 mm cortex screws as lag screws for its fixation.

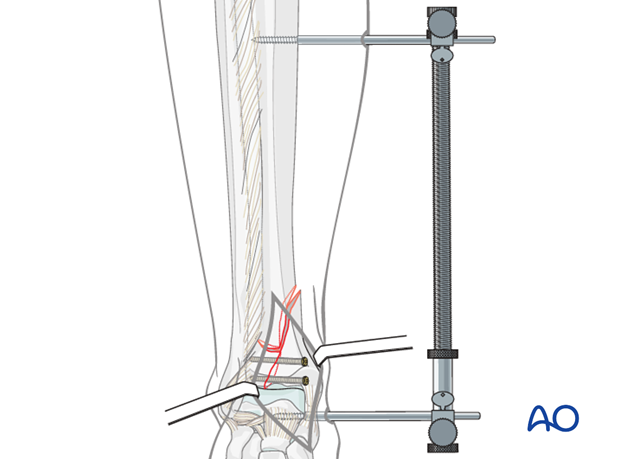

A distractor may aid the reduction and visualization. Medial positioning allows subcutaneous access to the tibia. A laterally based distractor requires a pin through the anterior muscular compartment but provides more efficient distraction of any associated fibular fracture, and correction of valgus deformities.

Schanz screws are positioned in safe zones of the tibial shaft and talar neck (or the calcaneal tuberosity). In case of previously applied joint-bridging fixator, the already existing Schanz screws can be used. Its tension may need to be adjusted during the procedure.

6. Metaphyseal reduction - First step

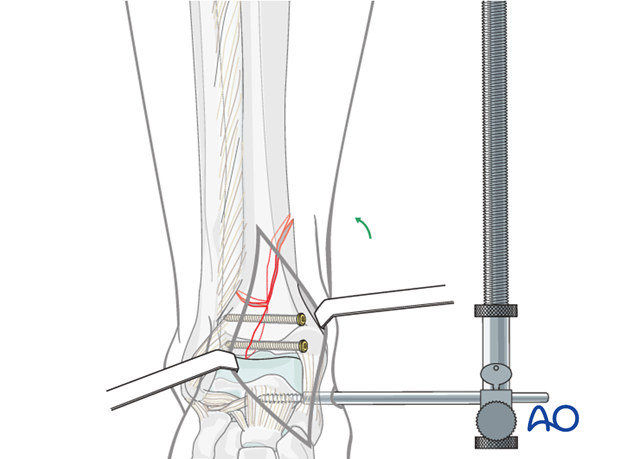

Adjusting distractor tension

The reconstructed articular block must be reduced to the diaphysis. This is done indirectly with fluoroscopic control through manipulation, distraction and plate application. The first step is to adjust the distractor tension for the best alignment. Rotation and axis alignment (AP and lateral) should be confirmed.

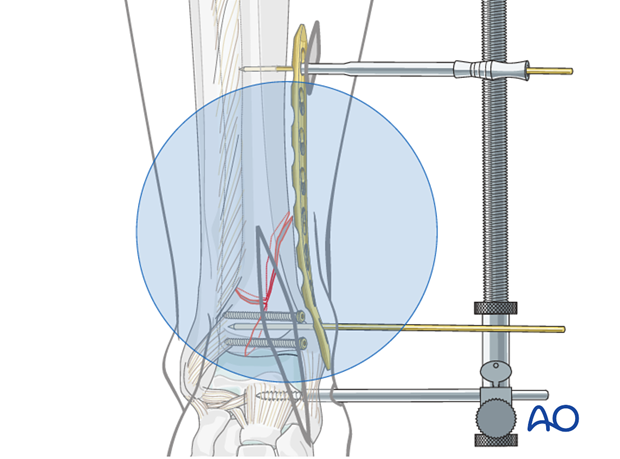

7. Plate insertion

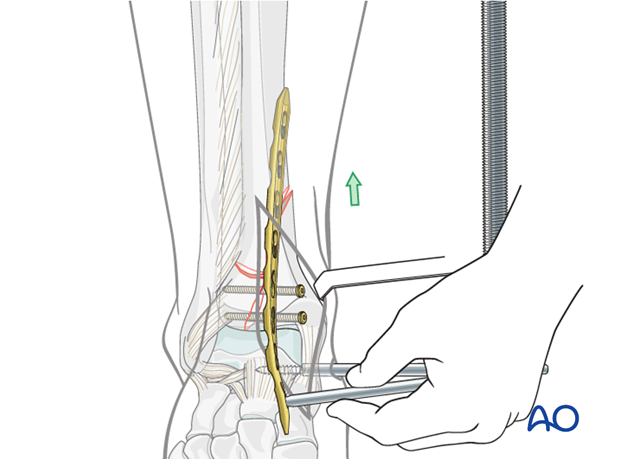

A tunnel is made with a blunt instrument close to the bone.

The contoured plate is inserted through the tunnel. The anteromedial subcutaneous tibial surface is a typical plate location, but the overlying tissues must be healthy enough to tolerate the procedure.

Note: Before definitive fixation, it is important to check that plate length, contouring and alignment.

8. Confirm plate position

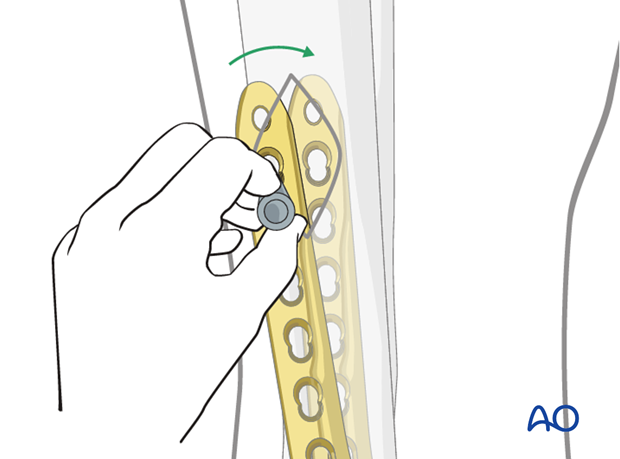

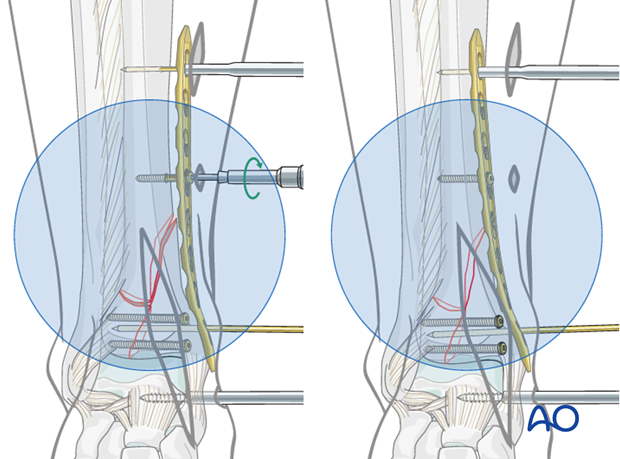

Plate positioning

A small incision is made at the proximal end of the plate, if possible well outside the fracture zone. The incision is a helpful guide for correct plate positioning. The plate can be repositioned using a threaded drill sleeve in the most proximal hole.

K-wires can be temporarily placed through screw holes to hold the plate position during fluoroscopy. Using a drill sleeve increases the wire’s stability.

The goal is to position the plate so that bringing it against the bone completes the fracture reduction.

Fluoroscopic assessment of the plate position and reduction requires care, and often several views.

9. Completion of metaphyseal reduction

Reduction of the metaphyseal fragment

A cortex screw is placed at the distal end of the diaphyseal segment with the implant correctly positioned and contoured. The screw is tightened to pull the plate to the bone and complete the metaphyseal reduction.

Strategic placement of the cortex screw near the fracture - so that positioning the plate recreates the tibial cortical outline - makes the plate act as a reducing tool.

Note: To achieve the desired reduction distractor adjustment and manipulation may be needed.

Lateral X-rays are performed to check that the plate, and the screws, is centered on the medial surface of the tibia. Eccentric screws, particularly if locking head variety, may not provide adequate fixation.

Pitfall - reduction screw compromises insertion of screws for articular fixation

The initial plate reduction screw positioning should not compromise the insertion of compression screws for articular fixation.

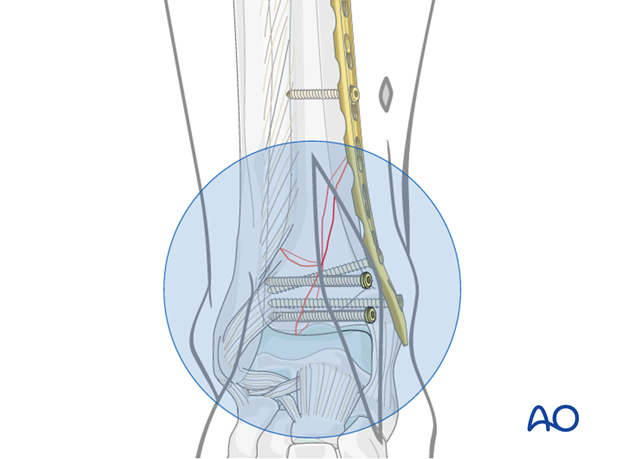

10. Fixation of the distal segment

The plate is attached to the distal segment with lag screws or fully threaded cortex or locking head screws. Lag screws are needed only to give additional support to the articular split. Otherwise, the screws serve primarily to anchor the plate and lagging is not necessary. Angular stable fixation provides better stability in osteoporotic bone. In the illustration, cortex screws have been used.

Reduction of the joint should always be confirmed with image intensification or x-rays. See also the content on assessment of reduction.

Pearl - fixation of the distal segment without independent lag screws

As an alternative to placing independent lag screws initially, the articular reduction can be maintained with a pointed reduction clamp, and perhaps K-wires, during manipulation of the distal metaphyseal fracture.

If this strategy is used, the distal plate screws must be lag screws to compress the articular surface.

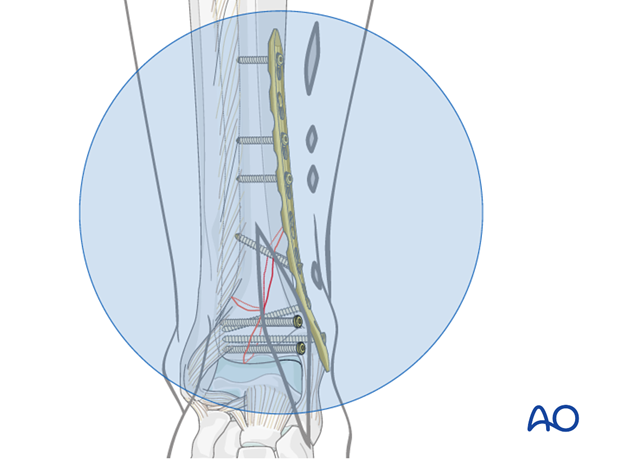

11. Finish plate fixation

Additional screws are added to obtain the desired stability. Their number and position depend on the individual fracture pattern. At least three screws should be inserted in the diaphyseal segment. Stability is increased with longer plates. It is not necessary to put a screw in every hole.

To enhance stability in certain fracture patterns (e.g., oblique or spiral), an additional lag screw can be placed through the plate to compress a non-comminuted metaphyseal fracture. Lag screws should be placed before locking head screws.

Depending upon the bone quality, plate length and fracture stability, conventional or locking head screws may be used in the other locations.

Final assessment

X-ray imaging at the end of the operation confirms anatomical restoration of length, alignment and rotation. See also the content on assessment of reduction.

12. Aftercare following plating

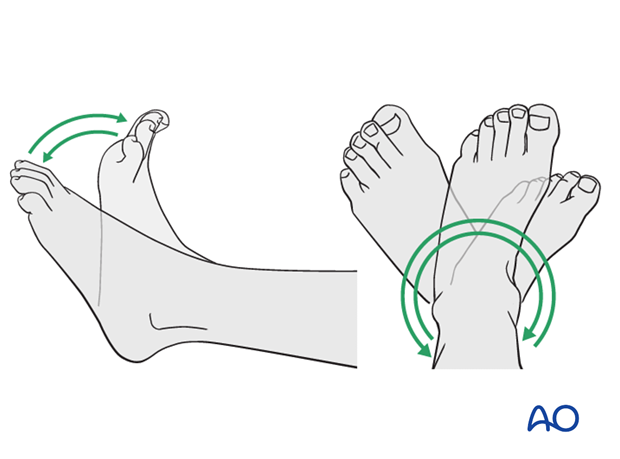

Leg elevation is recommended for the first 2-5 postoperative days. Physiotherapy with active assisted exercises is started immediately after operation. Immobilization is not necessary.

Mobilization

Starts depending on the wound healing with flat footed, weight of the leg weight bearing (10-20kg).

Follow up

Clinical and radiological follow-up is recommended after 2, 6 and 12 weeks. Depending on the consolidation, weight bearing can be increased after 6-8 weeks with full weight bearing usually after 3 months. Supervised rehabilitation with intermittent clinical and radiographic follow-up is advisable every 6-12 weeks until recovery reaches a plateau, typically 6-12 months after injury. Weight-bearing radiographs are preferable to assess articular cartilage thickness. Angular stable fixation may obscure signs of non-union for many months.

Implant removal

Implant removal may be necessary in cases of soft-tissue irritation by the implant (plate and/or isolated screws). The best time for implant removal is after complete remodeling, usually at least 12 months after surgery.