ORIF through Kocher-Langenbeck

1. General considerations

Sequence of the treatment

Pre-operative traction will be advantageous if the hip is subluxed medially.

For ORIF of transverse/posterior wall fractures with Kocher-Langenbeck approach, the following surgical sequence is common:

- Joint distraction and removal of incarcerated fragments

- Reduction of femoral head dislocation if not achieved closed on admission

- Reduction and stabilization of marginal impaction

- Reduction and fixation of the transverse element of the fracture

- Reduction and fixation of the posterior wall fragments

Planning/templating

Preoperative templating is essential for understanding the complexity of an acetabular fracture.

When using implants on the innominate bone, it is important to know the best starting points for obtaining optimal screw anchorage (see General stabilization principles and screw directions).

Patient positioning

The Kocher-Langenbeck approach can be performed in either the prone or lateral position.

If a hip dislocation is expected, the patient should be positioned in the lateral position. However, lateral positioning enhances the inward displacement of the ischiopubic segment due to the weight of the femoral head. Therefore, prone position is preferred and greatly facilitates the reduction of the ischiopubic segment.

The maintenance of knee flexion (at 90°) and hip extension throughout the procedure reduces tension on the sciatic nerve.

Extending the approach

In cases with large superior wall fragments, further visualization of the superior acetabulum may be necessary. This is achieved with a trochanter osteotomy extension.

Sciatic nerve injury

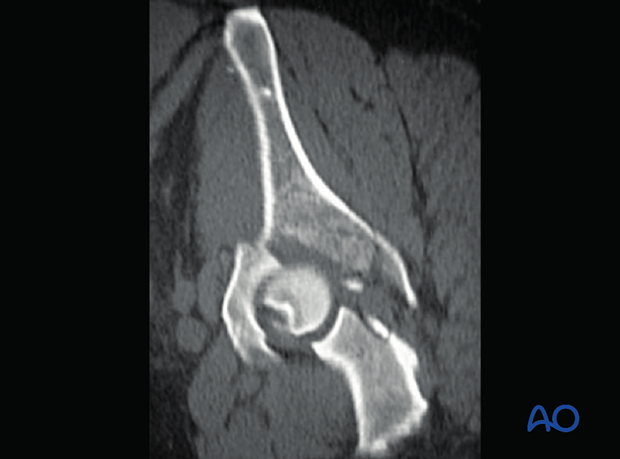

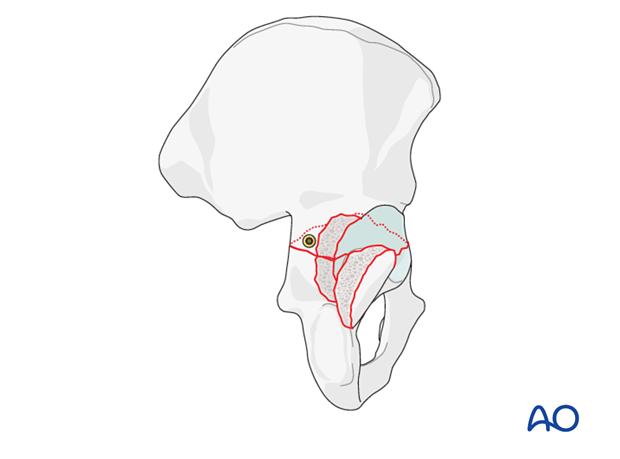

Posterior wall fractures, elemental and associated, usually result from posterior hip dislocation. The sciatic nerve may be injured. Post reduction CT will be used to evaluate the fracture characteristics. Watch for bone and cartilage impaction.

Teaching video

AO teaching video: Transverse and posterior wall fracture through Kocher-Langenbeck approach

2. Principles of reduction

Fracture reduction

Fracture reduction can be difficult and it is possible to reduce for example the posterior fracture apparently perfectly, but with significant anterior displacement still.

Indirect visualization

Unusually for a significant joint, articular reduction of acetabular fractures is indirect. The articular surface of the hip joint is not seen directly. Reduction must be assessed by the appearance of the extraarticular fracture lines and intraoperative fluoroscopic assessment. Some fracture lines are palpated manually but not seen directly such as transverse fracture lines on the quadrilateral plate.

Marginal impaction in the posterior wall fracture can be seen directly prior to final closure of the cortical fragment.

Quality of reduction

Posttraumatic arthrosis is directly related to the quality of reduction - the better the reduction, the greater the chance of a good or excellent result.

3. Joint distraction

Application of traction

Traction on the femur, laterally or distally, increases the joint space.

This will help:

- Expose the articular surface to assess reduction

- Remove loose fragments

Traction can be applied in several ways, including:

- Lateral manual traction applied via the greater trochanter (as demonstrated)

- Distal manual traction applied via a distal femoral traction pin

- With a femoral distractor (see below)

- With a traction table

In some surgeon’s experience, the use of a traction table post or other traction frame is helpful during this operation.

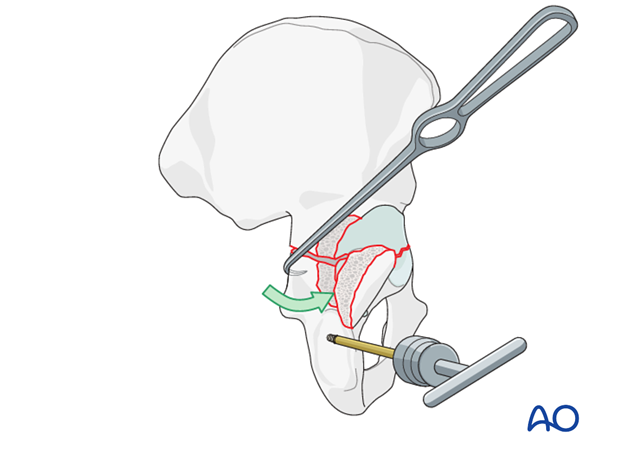

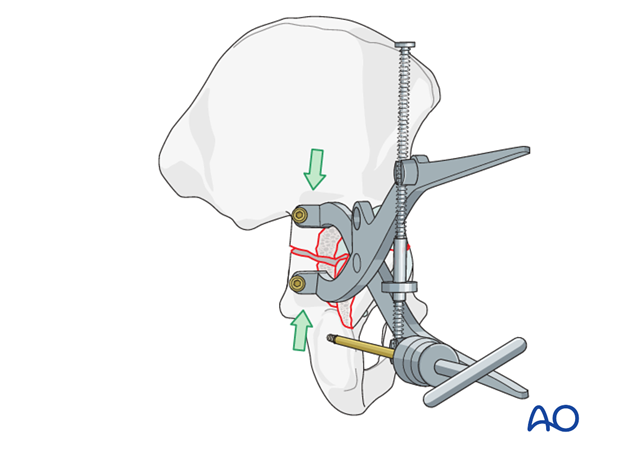

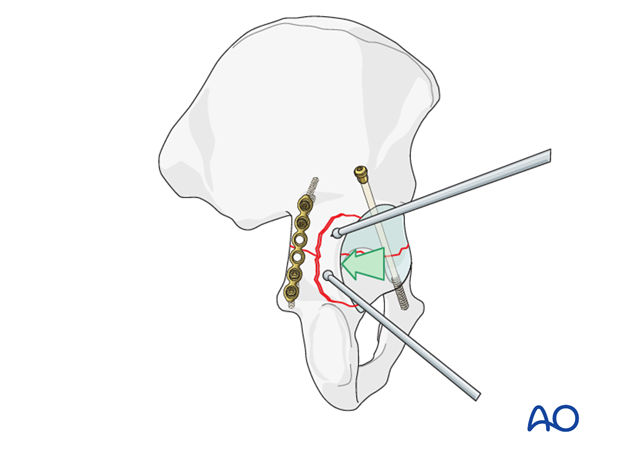

Traction with a femoral distractor

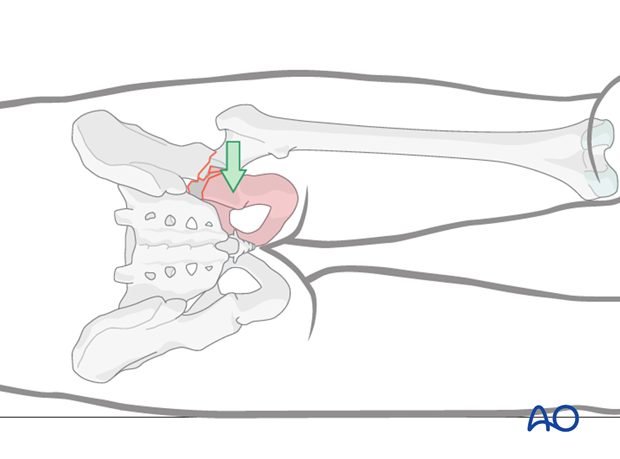

One way to apply traction is with a large distractor. This avoids both constant pulling and use of the fracture table, but does limit mobility of the hip. Properly placed, the distractor may properly realign the femoral head.

Insert a 5 mm Schanz screw into the sciatic buttress well above the level of the fracture. Place a second Schanz screw into the femur at the level of the lesser trochanter.

Tension on the distractor can be adjusted as needed for visualization or reduction.

Teaching video

AO teaching video: Use of the distractor on the pelvis

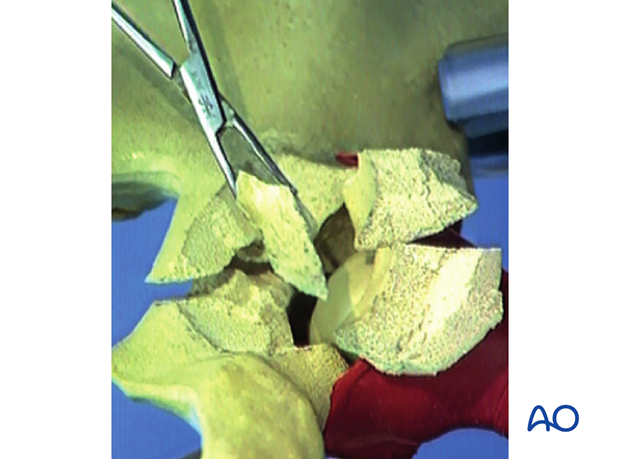

4. Cleaning of the fracture site

Femoral head subluxation

If the femoral head has been reduced in a closed fashion, subluxation of the joint to clear bony fragments would be required.

If the head is still dislocated then the joint can be cleaned before reduction.

Cleaning and irrigation

The posterior wall and attached capsule are reflected laterally, but additional capsular incisions may be necessary to see well inside the joint. Extraarticularly, the posterior wall fracture surface should be exposed subperiosteally.

Clean and irrigate the fracture site to prepare for direct reduction.

Remove loose bodies

Look for loose bodies preoperatively on the CT. Their removal, along with any blood clots, is essential for adequate cleaning of the joint.

5. Transverse fracture: reduction

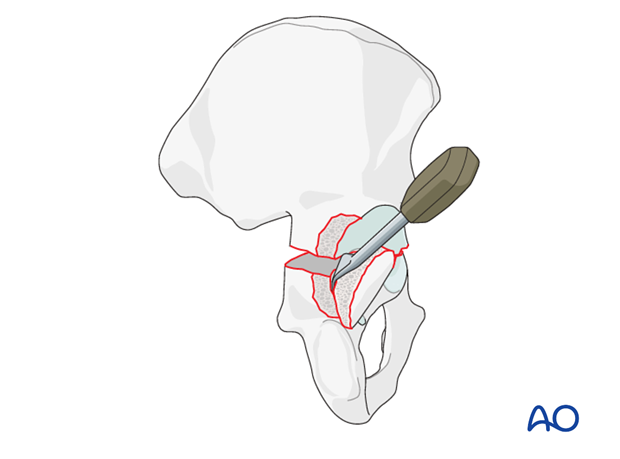

Use of a bone hook

A bone hook around the edge of the greater or lesser sciatic notch helps to assess and reduce the posterior part of the fracture.

First, check the mobility of the fracture by pulling on the hook. Mobility must be sufficient to permit reduction. If it is not, the fracture site should be further cleaned and irrigated.

It is possible to assess the reduction of the transverse fracture component by moving the posterior wall fragment and applying femoral traction. If the anterior end of the transverse fracture remains malrotated, a Schanz screw joystick may help achieve the reduction (see below for application of the screw).

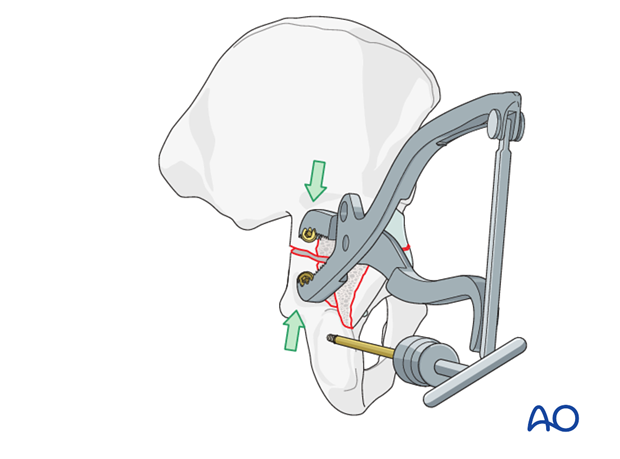

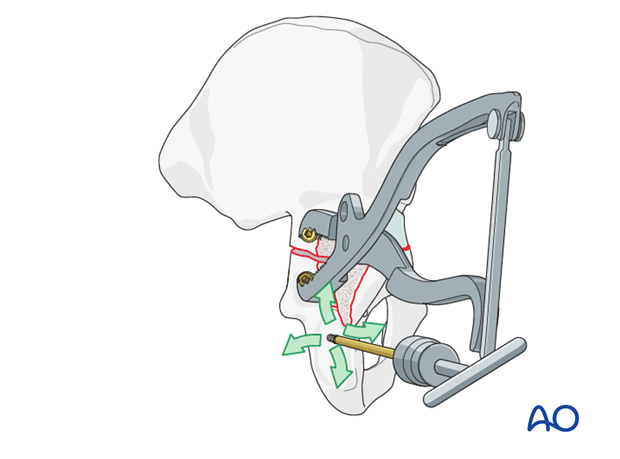

Use of a Farabeuf clamp

Final reduction can be obtained and compressed with a Farabeuf clamp applied to screws. Insert two 3.5 mm cortical screws, one on each side of the fracture, away from the site of definitive fixation. They should be long enough to protrude above the bone for the tips of the Farabeuf clamp. This clamp can also help to improve rotational alignment of the posterior end of the transverse fracture, as well as to close the gap between the fragments.

Use of a Jungbluth clamp

Instead of the Farabeuf clamp a Jungbluth clamp can be used. Its different screw anchorage allows this clamp to either distract or to compress the fracture.

Similarly, to the above description for the Farabeuf clamp, insert one 3.5 mm cortical screw each into

- The posterior column above the ischial tuberosity

- The superior portion of the iliac wing above the acetabulum.

The screws must be parallel to each other and perpendicular to the bone for easy application of this clamp. They should protrude approximately 1 cm above the cortical surface. Do not tighten the screws completely, thus allowing bone fragments to rotate underneath the reduction forceps.

The correct orientation (handle lateral to screws) of the Jungbluth forceps protects the sciatic nerve from being stretched.

Derotation of the distal (ischiopubic) fragment

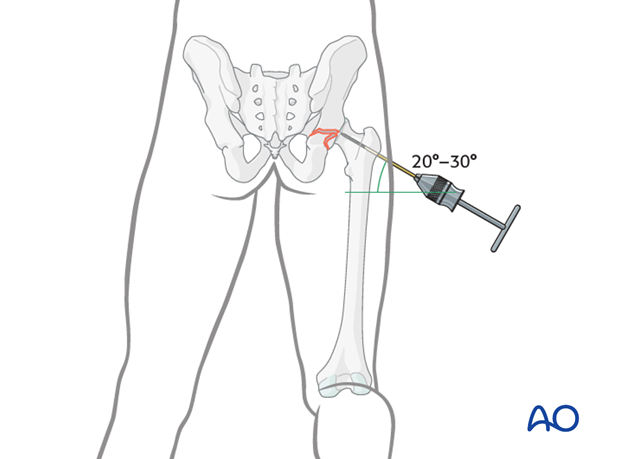

The trick to correct malrotation of the transverse fracture is to use a 5 mm Schanz screw on a T-handle.

Manipulation of the Schanz screw will help with improving the reduction. The combination of the clamp and the joystick, possibly with additional bone hook manipulation, helps obtain an anatomical reduction.

The screw is placed in the ischium, between the posterior rim of the acetabulum and the ischial tuberosity. Drill a 3.5 mm hole for a 5 mm Schanz screw directed so the screw handle remains at the edge of the wound. Insert the screw and attach a T-handle.

Free bone fragment

If possible, include any loose bone fragments in the final reconstruction, particularly if they form part of the articular surface. They may be stabilized with 2 mm screws or intraosseous wires.

Confirm reduction

After reduction maneuvers, check the fit of the greater sciatic notch and the retroacetabular surface by palpation. If a step can be felt along the quadrilateral surface and pelvic brim, there may still be displacement of the articular surface of the joint. Several adjustments may be necessary.

Care will need to be taken to ensure the anterior part of the transverse fracture is accurately reduced. This is not directly visualized from the Kocher-Langenbeck approach and can be assessed with a finger through the notch or with the image intensifier. Both the front and back must be accurately reduced.

Once rotation is correct, use a pelvic reduction forceps to stabilize the reduction and compress the fracture.

One point of a small angled-jaw pelvic clamp has been inserted through the greater sciatic notch onto the quadrilateral surface. The other point is outside the pelvis on the stable proximal fragment. This clamp helps maintain fracture reduction.

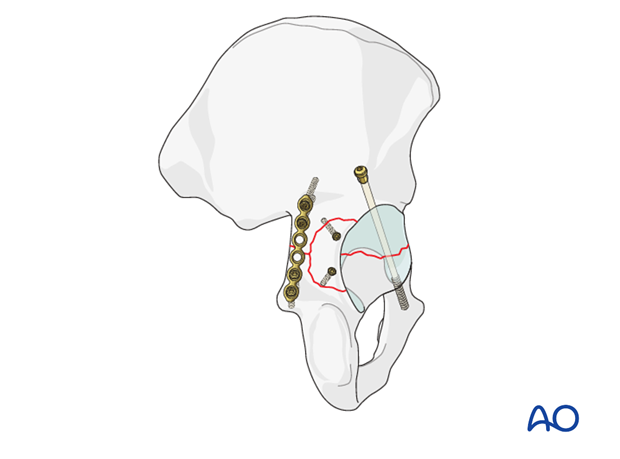

6. Transverse fracture: initial screw fixation

After obtaining anatomical reduction of the transverse fracture, there are two options for initial fixation.

Lag screw fixation of the transverse fracture

Most transverse fractures are oblique, exiting higher on the inner table of the pelvis than on the outer table such that a lag screw inserted above the fracture line will compress the fracture along its length.

A 3.5 mm (or 4.5 mm) cortical screw will be used.

The trajectory of the screw will be from the postero-superior aspect of the acetabulum towards the antero-inferior aspect, but will be shorter than a screw placed along the entire anterior column. It offers less robust fixation, but is more easily inserted.

Create a gliding hole with a 3.5 mm (4.5 mm) drill bit, depending upon chosen screw size. This should extend to the fracture line. Continue with the 2.5 mm (3.2 mm) drill bit, aimed towards the anterior column. Use an oscillating drill to protect the soft tissues. Insert a screw of the appropriate length. A washer is not usually necessary and allows the screw to sit flush with the bone such that subsequent plate fixation is not compromised.

Anterior column screw insertion

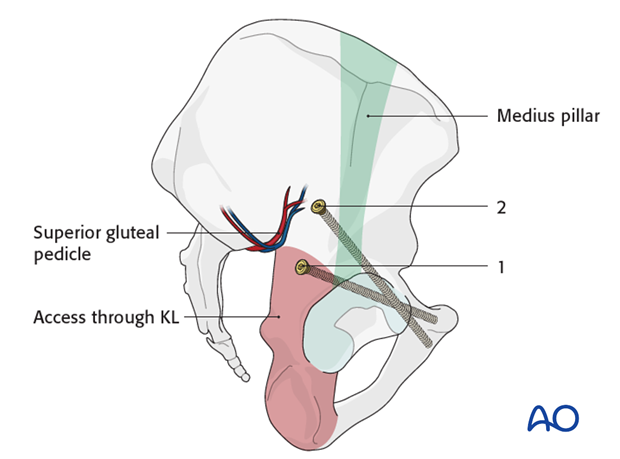

The anterior screw is placed obliquely from above the greater sciatic notch across the fracture. It is aimed anteriorly towards the root of the superior pubic ramus.

The starting point for the anterior column screw applied through the Kocher-Langenbeck exposure (1) is different than that applied through the extended iliofemoral (2). The exposure offered by the Kocher-Langenbeck approach is limited cranially and anteriorly by the superior gluteal neurovascular pedicle. Therefore, the anterior column screw entry point is placed percutaneously, or must be modified for the exposure.

The entry corridor for the screw applied through the Kocher-Langenbeck approach is generally 1-2 cm anterior (lateral) to the apex of the sciatic notch.

3.5, 4.5 or 6.5 mm screws can be used. In difficult cases, particularly obese patients, cannulated screws may be beneficial. It is often preferred to have two 3.5 mm screws instead of larger fragment fixation to provide additional torsional stability to the anterior portion of the ischiopubic segment.

Aids for correct screw placement

A finger inserted through the greater sciatic notch and along the quadrilateral lamina to the obturator foramen will help to direct the screw. The hip joint may be examined, with lateral femoral head distraction, to avoid placing the screw intraarticularly.

Fluoroscopic confirmation of this screw’s position is essential. During its insertion, one must remember the proximity of neurovascular structures to the superior ramus.

Check for posterior column reduction

Before final placement of the anterior screw, the reduction of the fracture where it crosses the posterior column should be reassessed, as only minor adjustments are possible once the anterior screw is inserted, adjusting with clamps if necessary. Reduction must be anatomical, particularly for transtectal fractures.

Once the anterior screw is finalized, reduction clamps may be removed to allow posterior fixation.

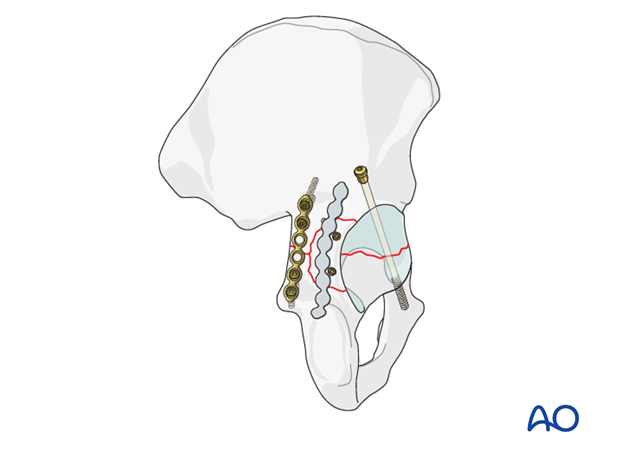

7. Transverse fracture: completing the fixation

Definitive fixation of the posterior part of the transverse fracture may be with either a combination of plates and screws, or with a further cannulated screw.

Lag screw fixation

If an anterior column screw has been used, depending upon the posterior location and orientation of the transverse fracture, it may be desirable for lag screw fixation posteriorly prior to plate application, although this is often unnecessary.

Such a screw may be placed from distal to proximal, as illustrated, or from proximal to distal.

Medial plate fixation

The most common fixation for the posterior aspect is a plate along the posterior column, placed medially, very near the greater sciatic notch. This may be short, as a more lateral plate will be added to support the posterior wall, and this adds additional fixation to the transverse fracture. These screws for this initial plate can be placed eccentrically to help compress the fracture.

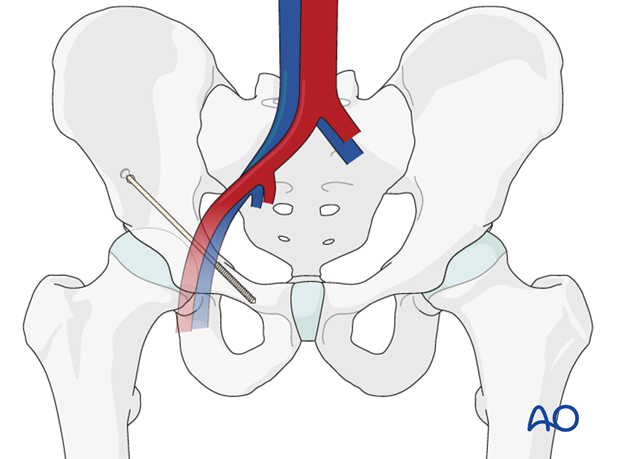

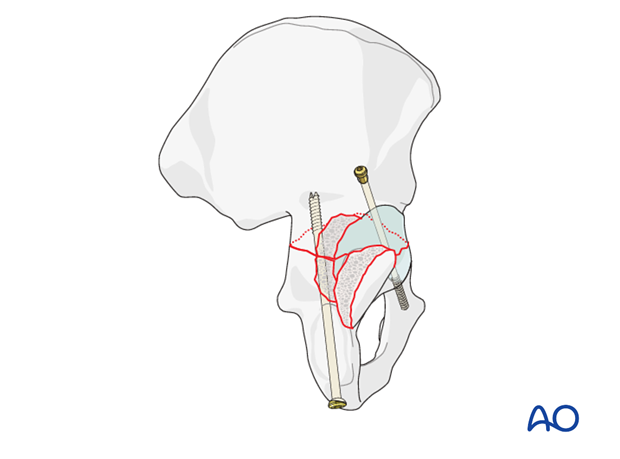

Posterior column screw fixation

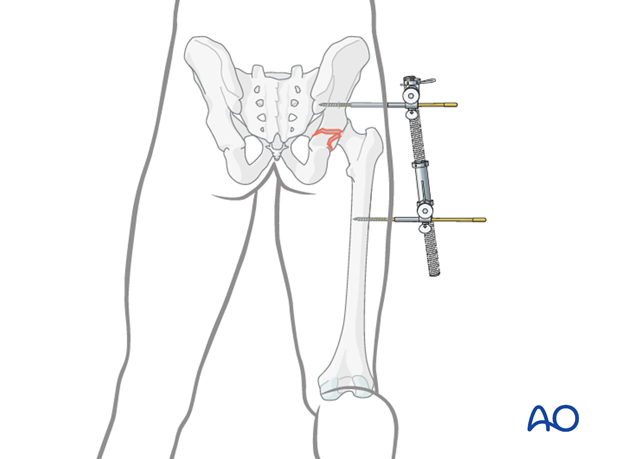

Particularly if the wall component is shallow, the posterior column is well stabilized with the insertion of a 7.3 mm partially threaded cannulated screw. This is inserted through a separate stab incision in the buttock crease over a guide wire.

The starting point is at the ischial tuberosity, and a finger in the greater sciatic notch is used to guide the wire and screw up the posterior column, exiting at the pelvic brim.

Care should be taken to protect the sciatic nerve at the level of the ischial tuberosity.

The use of a screw aids the placement of the posterior wall plate as it increases the freedom of placement of the wall plate.

This is commonly referred to as the “butt screw”.

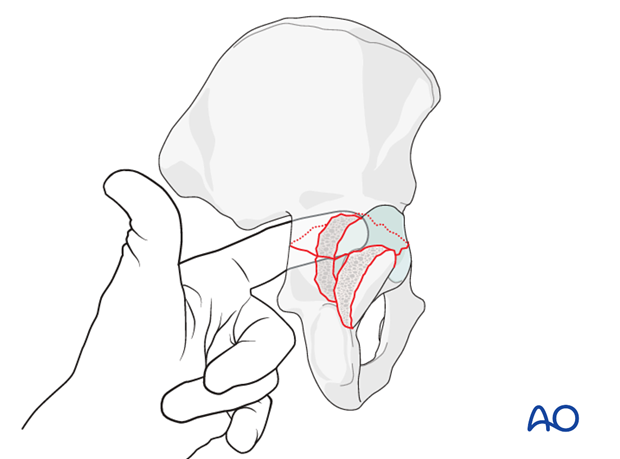

8. Posterior wall: reduction

Reduction of a free fragment

After release of the traction, the femoral head is reduced into the joint. Reconstruction of the posterior wall begins with replacement of any free osseocartilaginous fragment, so that its articular surface is congruent with the femoral head. The wall fragments must be reduced anatomically, and fixed in place. Any free fragment will be held reduced by the overlying posterior wall fragments.

Reduction with ball spike pushers, dental picks, or elevators

Reduce the posterior wall fragments, with attached hip capsule. Use ball spike pushers, dental picks, or elevators.

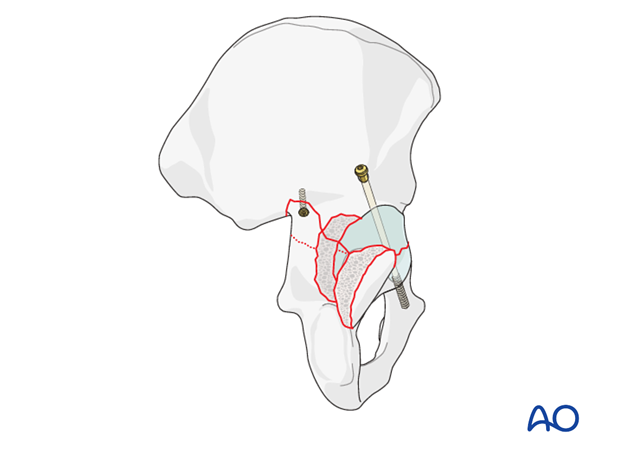

9. Posterior wall: initial fixation

This figure shows the wall fragment reduced and fixed with two lag screws after initial posterior column fixation with a plate. Another plate must be added across the wall fracture to obtain secure fixation.

Commonly, two 2.7 mm cortical screws are used. If the fragment is large enough, a 3.5 mm screw can be used, but it should be a lag screw, with a 3.5 mm gliding hole drilled in the wall fragment, and 2.5 mm thread hole in the underlying bone. It is important to avoid the joint when placing these screws.

With the patient in the prone position a horizontal orientation of the drill bit helps direct the drill clear of the joint. However, this requires the surgeon’s careful attention and x-ray evaluation of each such screw.

10. Posterior wall: completing the fixation

Choice and contouring of plate

There are both straight and curved pelvic reconstruction plates. A curved plate usually works well on the posterior wall. Any plate must be contoured and positioned for optimal support of the wall fragments.

To aid contouring, a malleable template is first fit to the bone. This provides a model for contouring the 3.5 mm reconstruction plate.

The plate is slightly undercontoured, over the convexity of the posterior column, compared with the template. This is so that it compresses the fragments slightly as its screws are tightened.

Application of the plate

First fix the distal end of the plate with a screw into its concave bend, just above the superior pole of the ischial tuberosity.

Drill a 2.5 mm hole before insertion of a 3.5 mm cortical screw but do not completely tighten it yet.

Position the plate optimally, and hold it with a ball spike pusher during the next step.

Next, insert the most proximal screw. Drill eccentrically, closer to the proximal end of the hole, so that tightening this screw tensions the plate, analogous to a dynamic compression plate.

Addition of remaining distal and proximal screws should improve final contouring, to provide uniform compression of the posterior wall fragments. The screws in the mid-portion of the plate should be omitted because of the underlying hip joint. Each major posterior wall fragment should have a screw, either through the plate and into good underlying bone, or inserted outside the plate.

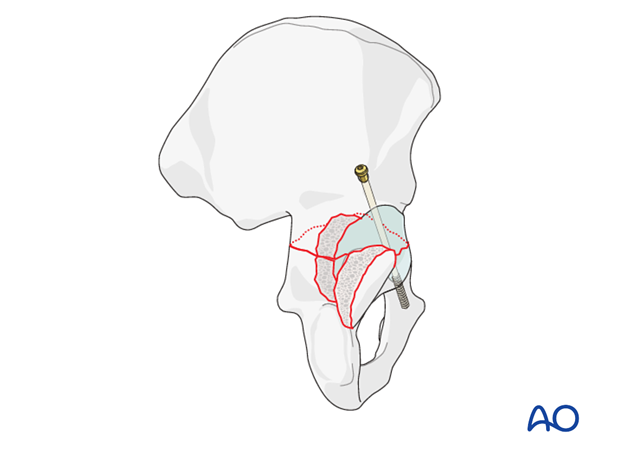

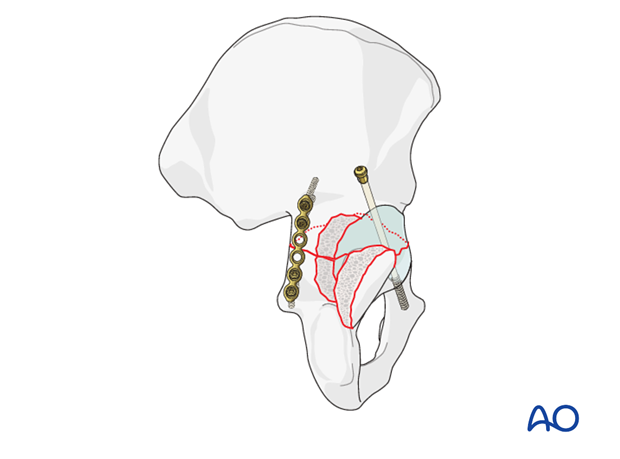

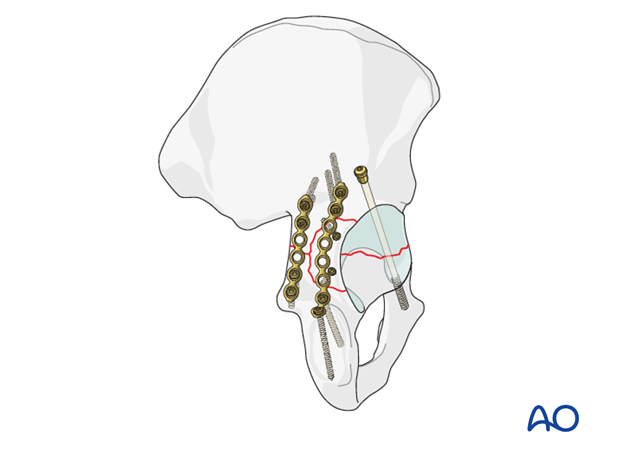

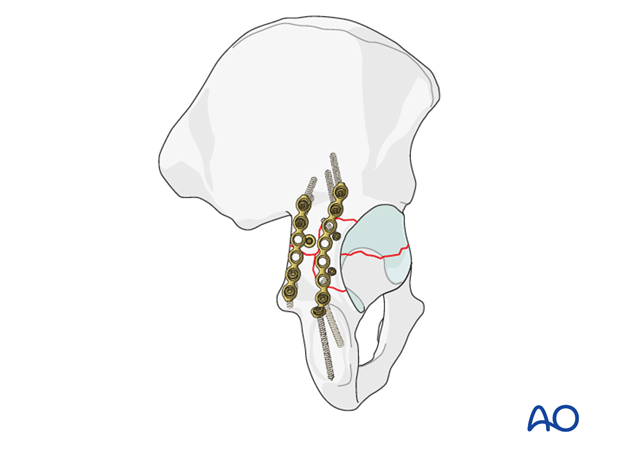

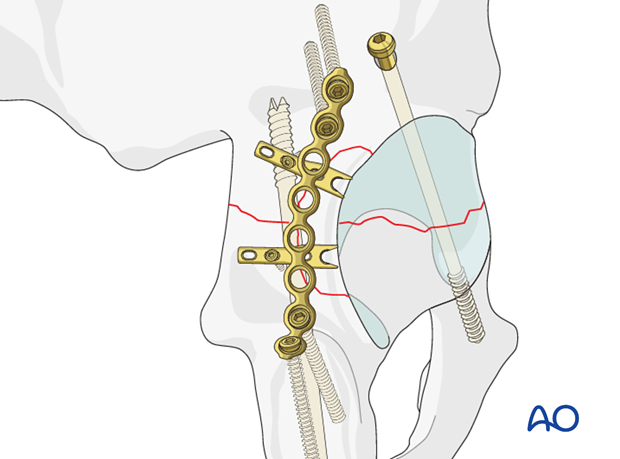

Examples for completed fixation

This example shows the use of an initial lag screw with posterior plates.

The medial one, near the sciatic notch, was placed first to fix the posterior end of the transverse fracture. The second plate fixes the posterior wall component, and adds additional posterior column support with separate small lag screws in the posterior wall fragment.

The second example has used a posterior column screw to stabilize instead of a medial plate.

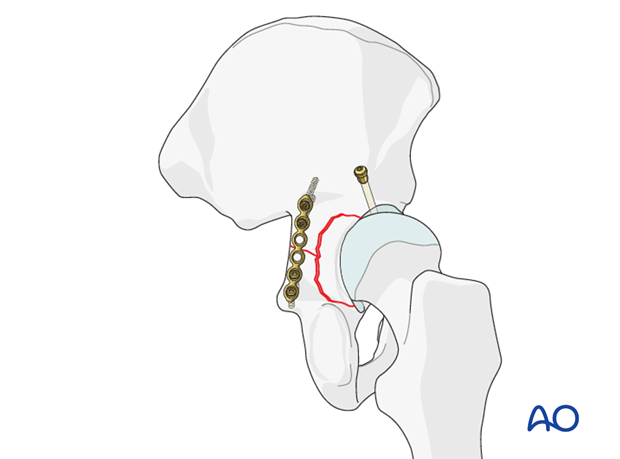

Spring hook plates

Stabilization of the posterior wall fragments sometimes requires spring hook plates to resist shearing forces on the fragment which are inserted either instead of lag screws, or before them to resist the shear created by the compression.

The spring hook plates should extend medially beyond the posterior wall buttress plate. These supplementary plates provide additional buttress support for the comminuted fragments.

The hooks must press on the bone fragments and not into the labrum.

Spring hook plates are available pre-contoured or made from small fragment one third tubular plates. For details see the corresponding basic technique.

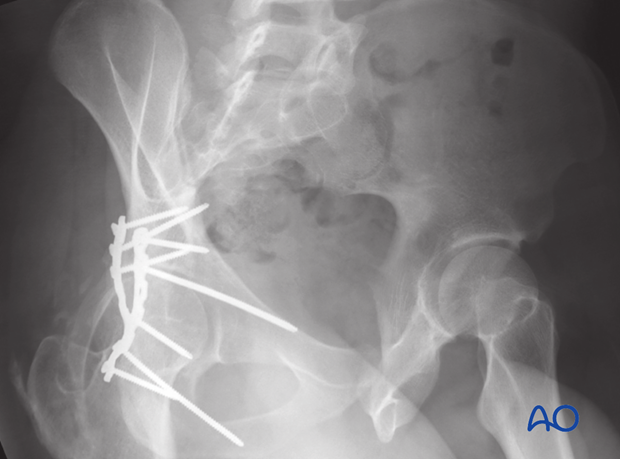

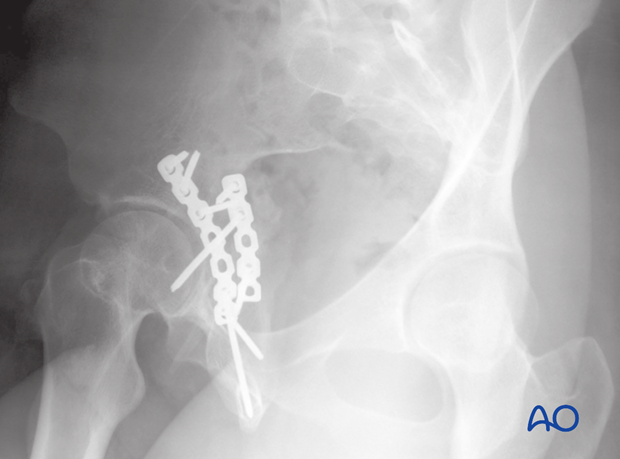

11. Radiographic assessment

Intraoperative confirmation of hardware position

During reduction and fixation, take fluoroscopic images in AP, iliac, and obturator oblique views to confirm reduction and/or screw placement.

In particular to confirm that posterior wall lag screws are extraarticular an image exposed with the fluoroscope’s central ray superimposed on the long axis of the screw is taken.

Final radiographic assessment

Once all fixation is in place, confirm the appropriate appearance of AP, obturator oblique and iliac oblique views and check the location of any screw that is placed near the hip joint.

The AP view should be inspected to assure that congruence has been obtained. The femoral head should have the same relationship to the radiological roof, the anterior rim and the posterior rim as on the contralateral side.

If the low anterior column was affected, the obturator foramen profile and symphysis should be inspected to assess the quality of the distal reduction.

The lag screw should be seen to be crossing the level of the transverse fracture, and the lower plate screws should be directed down the ischium and not in the direction of the posterior wall.

If a posterior wall fragment was involved, it should be seen as reduced and stabilized on this image.

Iliac oblique view should be inspected to ensure that the posterior column reduction is anatomic. The screws directed down the posterior column should be inspected and verified as extraarticular.

Postoperatively, obtain formal high-quality radiographs of AP and both oblique views.

12. Postoperative care

During the first 24-48 hours, antibiotics are administered intravenously, according to hospital prophylaxis protocol. In order to avoid heterotopic ossification in high-risk patients, the use of indomethacin or single low dose radiation should be considered. Every patient needs DVT treatment. There is no universal protocol, but 6 weeks of anticoagulation is a common strategy.

Wound drains are rarely used. Local protocols should be followed if used, aiming to remove the drain as soon as possible and balancing output with infection risk.

Specialized therapy input is essential.

Follow up

X-rays are taken for immediate postoperative control, and at 8 weeks prior to full weight bearing.

Postoperative CT scans are used routinely in some units, and only obtained if there are concerns regarding the quality of reduction or intraarticular hardware in others.

With satisfactory healing, sutures are removed around 10-14 days after surgery.

Mobilization

Early mobilization should be stressed and patients encouraged to sit up within the first 24-48 hours following surgery.

Mobilization touch weight bearing for 8 weeks is advised.

Weight bearing

The patient should remain on crutches touch weight bearing (up to 20 kg) for 8 weeks. This is preferable to complete non-weight bearing because forces across the hip joint are higher when the leg is held off the floor. Weight bearing can be progressively increased to full weight after 8 weeks.

With osteoporotic bone or comminuted fractures, delay until 12 weeks may be considered.

Implant removal

Generally, implants are left in situ indefinitely. For acute infections with stable fixation, implants should usually be retained until the fracture is healed. Typically, by then a treated acute infection has become quiescent. Should it recur, hardware removal may help prevent further recurrences. Remember that a recurrent infection may involve the hip joint, which must be assessed in such patients with arthrocentesis. For patients with a history of wound infection who become candidates for total hip replacement, a two-stage reconstruction may be appropriate.

Sciatic nerve palsy

Posterior hip dislocation associated with posterior wall, posterior column, transverse, and T-shaped fractures can be associated with sciatic nerve palsy. At the time of surgical exploration, it is very rare to find a completely disrupted nerve and there are no treatment options beyond fracture reduction, hip stabilization and hemostasis. Neurologic recovery may take up to 2 years. Peroneal division involvement is more common than tibial. Sensory recovery precedes motor recovery and it is not unusual to see clinical improvement in the setting of grossly abnormal electrodiagnostic findings.