Trochanter osteotomy of the acetabulum

1. Introduction

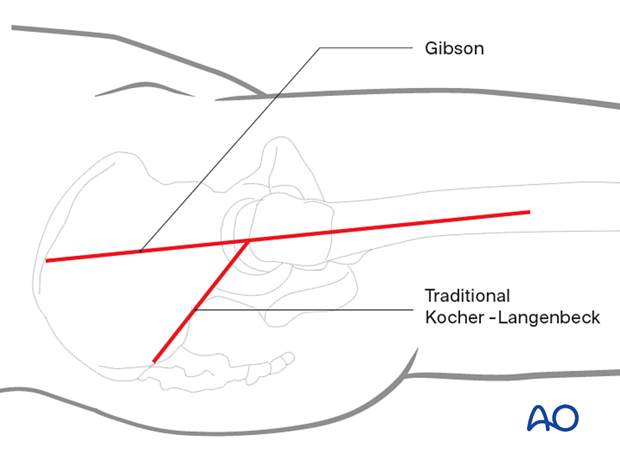

If further anterior and cranial exposure is required than allowed by the confines of the Kocher-Langenbeck approach, the Gibson interval can be utilized. This interval is anterior to the gluteus maximus and therefore allows exposure to the AIIS. The additional anterior exposure is facilitated with hip flexion and rotation. Therefore, lateral positioning is commonly preferred.

The trochanter osteotomy (digastric slide), through either the Kocher-Langenbeck or Gibson interval, can be combined with surgical dislocation of the hip to allow direct articular access.

The maintenance of knee flexion (at 90°) and hip extension throughout the procedure reduce tension on the sciatic nerve.

Exposure

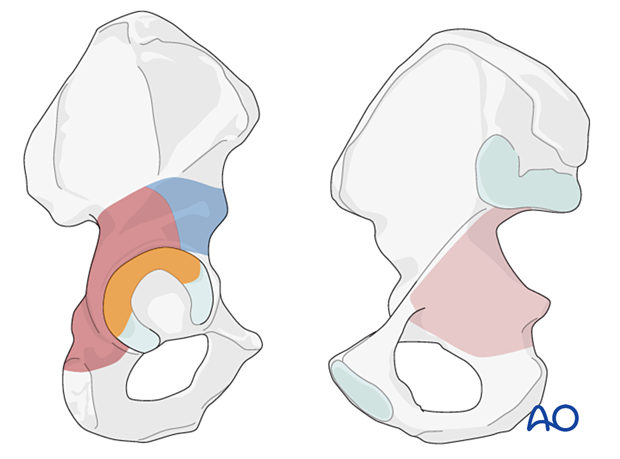

The addition of the trochanter osteotomy to the Kocher-Langenbeck or Gibson exposure provides improved access to the cranial and anterior aspects of the acetabulum and supra-acetabular surface.

The dark brown area demonstrates the exposure associated with the osteotomy and the patient positioned prone.

The blue region demonstrates the additional exposure possible through the Gibson interval with the patient positioned lateral. The more anterior interval and the additional hip motion allow exposure to the anterior inferior iliac spine, not possible with the patient prone.

The intraarticular region outlined in orange demonstrates the additional exposure associated with complete hip dislocation.

The area in light brown can be accessed by palpation and allow clamp placement.

2. Skin incision

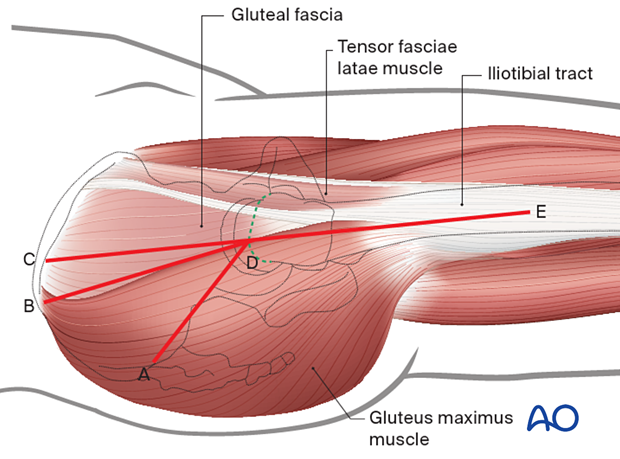

The trochanter osteotomy can facilitate exposure to the cranial and anterior retroacetabular surfaces in conjunction with several surgical intervals. Originally the osteotomy was proposed utilizing the Kocher-Langenbeck exposure (demonstrated by angled line ADE). The modification of the exposure, described by Gibson, used a more anterior interval without violation of the gluteus maximus muscle fibers (angled line BDE). The ‘modified’ Gibson approach (straight line CDE) is the incision most commonly utilized in contemporary practice.

The following sections represent the approach through the Gibson variation.

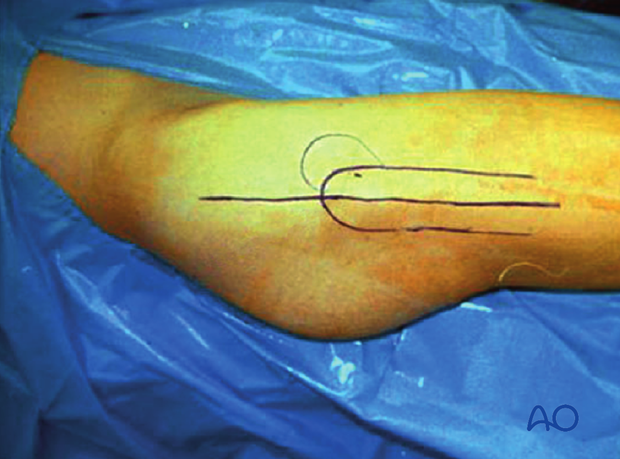

With the hip in a neutral rotation position, a long straight lateral incision is made (modified Gibson variation).

The usual skin incision begins 10–15 cm proximal to the trochanter and extends an additional 10–15 cm along the proximal lateral femur.

The total length of the incision is dictated by the body habitus of the patient.

3. Superficial surgical dissection

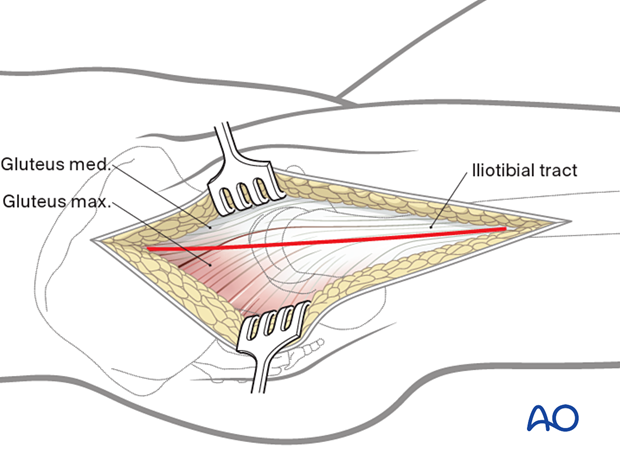

Deepen the incision through subcutaneous fat. The Gibson interval between the gluteus maximus and medius must be delineated. This is accomplished more easily in the proximal portion of the wound. This fascial incision is continued distally to split the iliotibial tract longitudinally.

In some cases, it may be necessary to release a portion of the gluteus maximus tendinous insertion onto the femur in the distal portion of the wound. This facilitates posterior retraction in the larger patient.

The gluteus medius fascia is mobilized with the gluteus maximus muscle belly allowing preservation of important vascular supply from the superior gluteal artery.

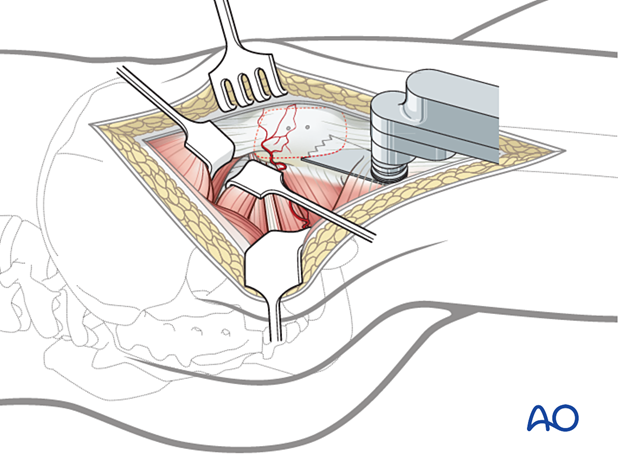

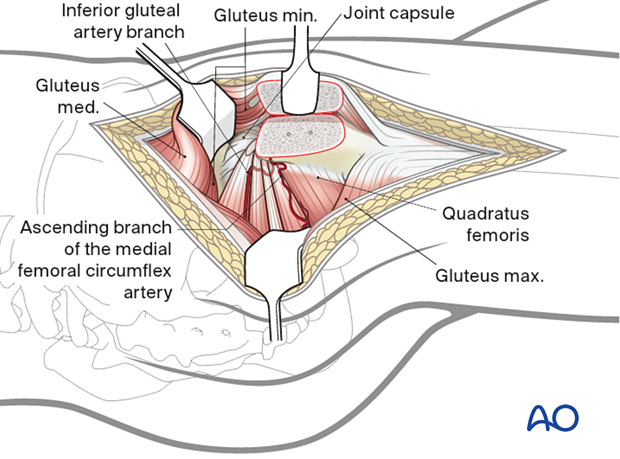

4. Deep dissection

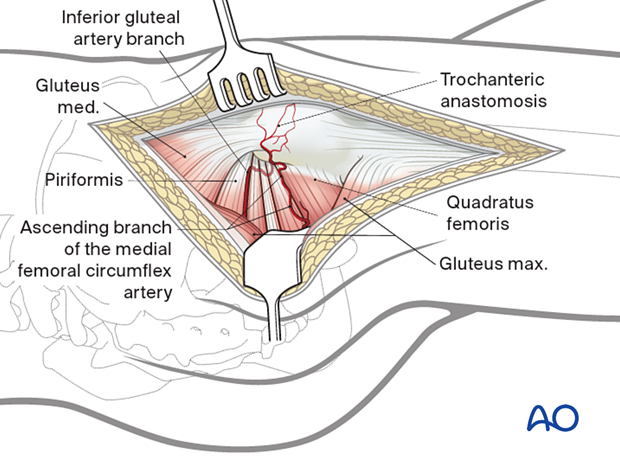

Two vascular landmarks assist in the identification of external rotator anatomy. The trochanteric anastomosis communicates with the ascending branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery at the cranial border of the quadratus femoris.

The second landmark is provided by the inferior gluteal artery branch, which traverses the inferior border of the piriformis tendon. This vessel also anastomoses with the ascending medial femoral circumflex artery.

Evaluate the sciatic nerve

Next, the sciatic nerve is localized in its path posterior to the quadratus femoris.

It is traced proximally to the level of the piriformis, and any anomalies in neural anatomy are noted.

In the majority of the cases, the sciatic nerve is a single trunk that passes anterior to the piriformis as it enters the greater sciatic notch. In these cases, the piriformis is left attached to the trochanter, and no further dissection is carried out in the zone of the short external rotators.

Note: In cases where the sciatic nerve is bifid or penetrates the substance of the piriformis, it may be prudent to release the piriformis 1 cm posterior to the trochanter. This will limit the potential traction on the nerve if surgical dislocation of the femoral head is required.

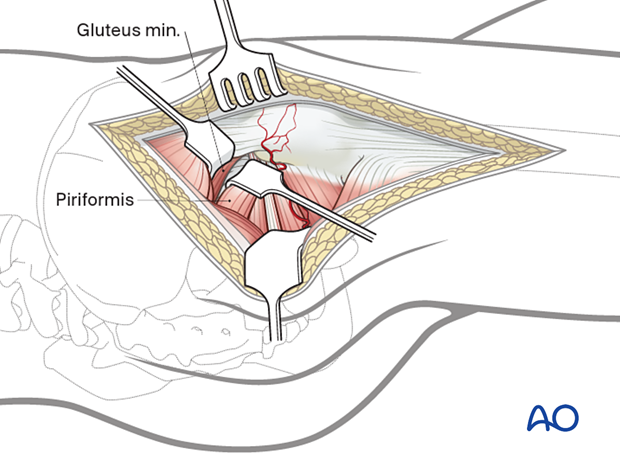

Develop the piriformis muscle

This requires inferior retraction of the piriformis and superior retraction of the medius. The minimus is sharply mobilized, beginning along its inferior fascial border. The release extends posteriorly to the greater sciatic notch, taking care to avoid injury to the superior gluteal neurovascular bundle. The initial anterior dissection proceeds to the mid supra-acetabular area.

Develop the minimus-piriformis interval

Next, the interval between the piriformis and gluteus minimus is developed.

This requires inferior retraction of the piriformis.

The minimus muscle should be protected because it carries the circumflex vessels. It is sharply released from the retroacetabular surface.

Trochanter osteotomy

The plane of the trochanter osteotomy is then prepared by cauterizing the trochanteric anastomotic vessels.

It may be useful to predrill the trochanter for subsequent reattachment prior to the osteotomy.

The osteotomy is then carried out from the tip of the trochanter to the base of the vastus tubercle using a saline-cooled oscillating saw. A small portion of the medius tendon is left temporarily attached to the intact femur until the trochanter can be mobilized. This provides an additional aid to prevent injury to the retinacular vessels caused by an excessively thick osteotomy.

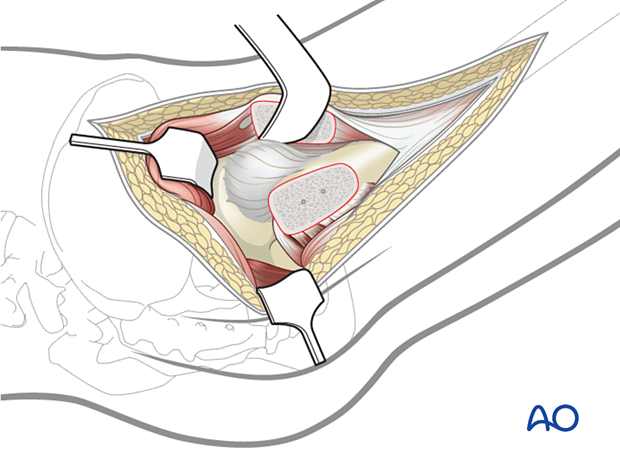

Anterior exposure and mobilization of gluteus minimus

The vastus lateralis fascia is incised from the vastus tubercle distally at a distance of 5–8 cm to allow extra periosteal mobilization of the proximal lateralis muscle belly with the trochanteric segment.

The trochanter is progressively everted utilizing a Hohmann retractor placed over the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter. Now, the small remaining gluteus medius attachment to the intact trochanteric ridge is released. At times, the piriformis insertion will be partially attached to the mobile trochanteric fragment. This should be released as the trochanter is everted.

Flex and externally rotate the hip to improve anterior exposure.

This allows complete mobilization of the gluteus minimus from the retroacetabular surface along the superior capsule to its femoral insertion along the anterior aspect of the trochanter.

The minimus insertion may also straddle the trochanter osteotomy. If so, it must be released from the intact femur to allow full trochanteric mobilization.

Hemicircumferential view of the acetabular rim

Exposure of the anterior capsule requires mobilization of the proximal portion of the vastus intermedius.

Once this is achieved, a hemicircumferential view of the acetabular rim and capsule is provided. This starts posterior and inferior to the retracted piriformis tendon and extends anteriorly around the acetabulum to the level of the reflected head of the rectus.

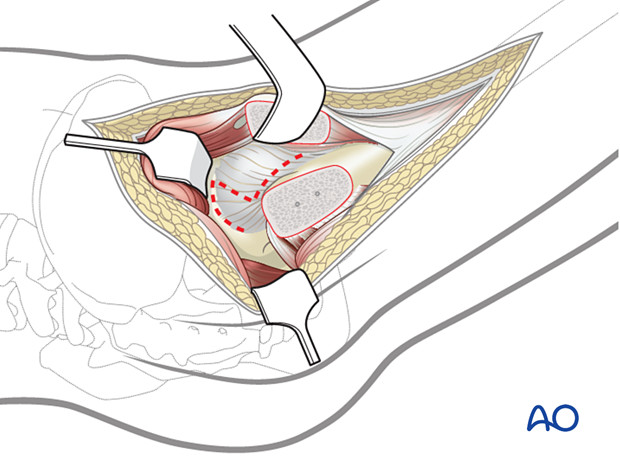

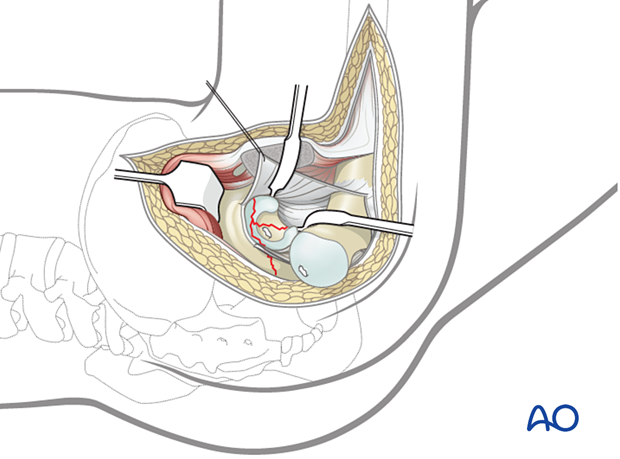

Capsulotomy

Intraarticular visualization is provided by a Z-shaped capsulotomy. The capsular incision must remain anterior to the lesser trochanter to avoid damaging the medial femoral circumflex artery.

This aids reduction of fractures that do not have a posterior or superior wall component. Retraction sutures are useful.

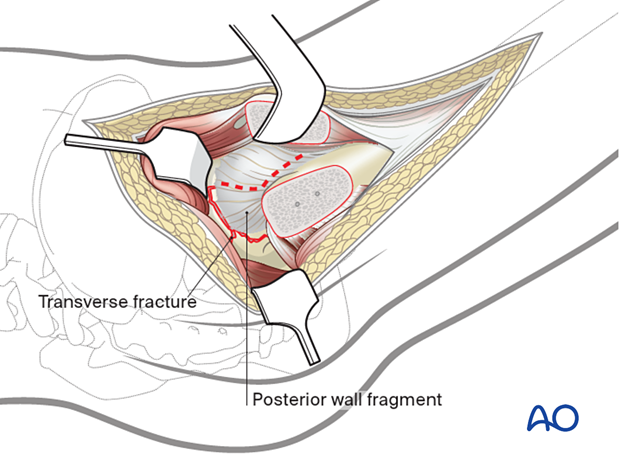

When a posterior wall fracture is present, the capsular pedicle to the wall fragments must be preserved. The capsulotomy is modified to incorporate the posterior wall at its margin.

The wall fragment(s) are mobilized and retracted to allow joint visualization. The labrum is typically intact at the anterior aspect of the wall fragment; thus, the fragment is retracted anteriorly, as illustrated. Articular exposure is accessed through the fracture line with femoral distraction.

For many fractures, the surgical exposure is now complete. Reduction and fixation of most posterior wall and column fractures can be accomplished despite the intact piriformis and conjoint tendon.

If further distal exposure is required for fracture reduction or osteosynthesis, the piriformis and conjoint tendon of the obturator internus and gemelli muscles can be released. As with the Kocher-Langenbeck exposure, these tendons should be transected at least 2 cm posterior to their insertion on the greater trochanter to protect the femoral head circulation.

5. Option: dislocation of the hip joint

“Figure of four” extension of the approach

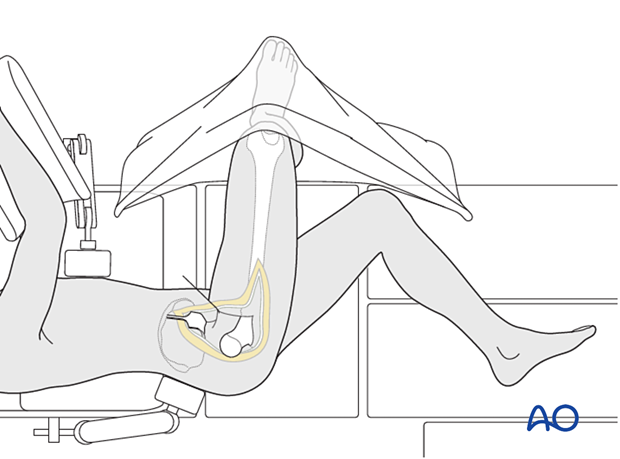

More complex fracture patterns may require extension of this approach to include anterior surgical dislocation.

This is accomplished by careful placement of the involved limb in a “figure-four” position (flexion to 90° combined with adduction and external rotation).

A sterile pouch is required for this maneuver. Divide the ligamentum teres with a pair of curved scissors to reduce the force required for dislocation.

Dislocation of the femoral head

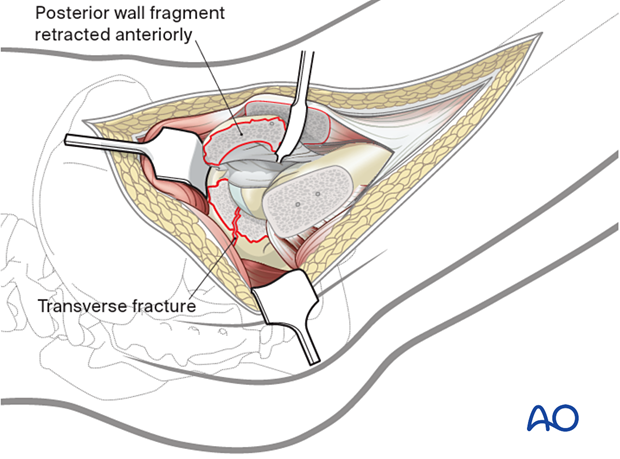

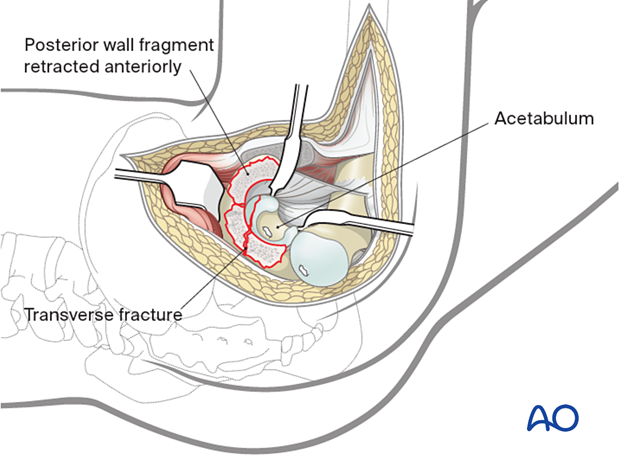

With the femoral head dislocated and the posterior wall fragment reflected anteriorly, one can now visualize the entire joint.

In this illustration, the extension of the transverse fracture through the anterior column can be directly visualized as the femoral head has been dislocated posteriorly.

Visualization of anterior column of a T-shaped fracture

In this example of a transtectal T-shaped fracture, dislocation allows evaluation of the reduction of the anterior portion of the ischiopubic segment.

In this illustration, the anterior limb of the T-shaped fracture can be visualized and the reduction assessed. This visualization is not possible with the femoral head reduced.

However, because of soft tissue limitations, it is usually necessary to relocate the hip for implant insertion. Therefore, the sequence of dislocation and reduction may have to be repeated multiple times during the reconstruction.

6. Wound closure

When the reconstruction is completed, the capsule is closed loosely to allow drainage of any secondary hemarthrosis.

The trochanter is then reattached with lag screws. The number (2–3) and diameter (3.5–4.0 mm) of screws utilized are dependent on bone density.

The vastus lateralis fascia is repaired, and the short rotator tendons are reapproximated.

Deep drains are placed as needed. The gluteus maximus tendon is repaired, and lastly, the iliotibial tract and gluteal fascia are closed.

Subcutaneous drains follow, and subcutaneous and skin closure are completed.