Open reduction; plate and screw fixation

1. Introduction

General considerations

Plating is the standard technique for treating forearm fractures in adults and is therefore best considered for skeletally mature or nearly mature children.

Children with open physes have thick active periosteum favoring stability and rapid healing with the ESIN method. Where such techniques are unavailable plating may be used in younger children.

If technically possible, ESIN is biologically favored. If plating is used, soft-tissue and periosteal stripping should be minimized.

Plating of oblique or spiral forearm shaft fractures

Plating of pediatric forearm shaft fractures follows the technique for plate fixation in adults.

For oblique or spiral forearm shaft fractures, interfragmentary compression can be achieved by one of the following techniques:

- Lag screw outside the plate

- Lag screw through the plate

- Compression plate with consecutive lag screw through the plate

This results in absolute fracture stability.

Large wedge fragments may be fixed to one of the main segments before plate fixation with a lag screw, placed through or outside the plate.

For unstable multifragmentary forearm shaft fractures, bridge plating may be applied. This results in relative fracture stability.

2. Principles

Instruments and implants

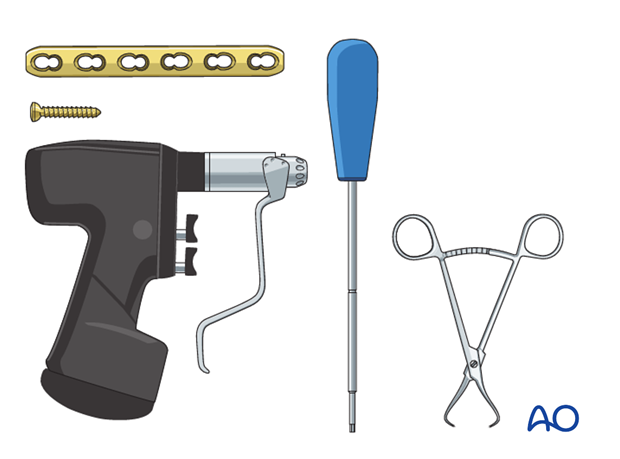

A small fragment set consists of:

- 2.7 or 3.5 mm plates and screws

- Power driver

- 2.7 or 3.5 mm insertion set

Compression by lag screw

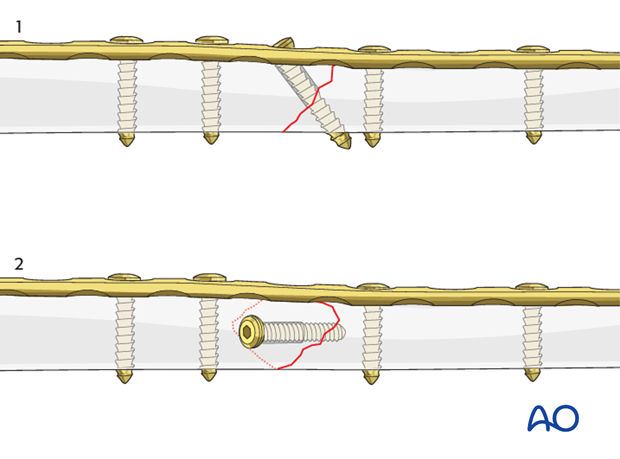

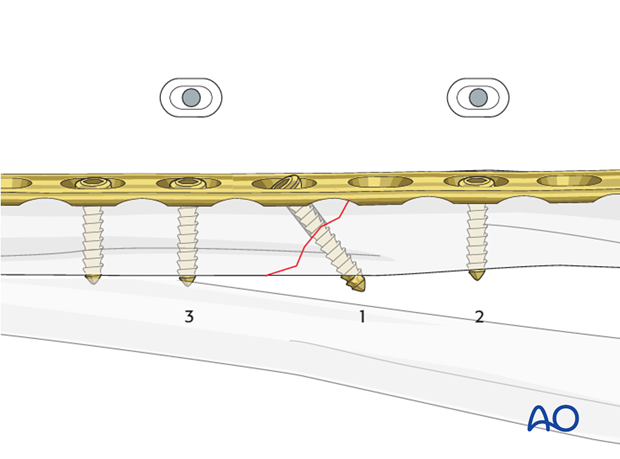

For interfragmentary compression a lag screw can be inserted either through a plate hole (1) or separate from the plate (2).

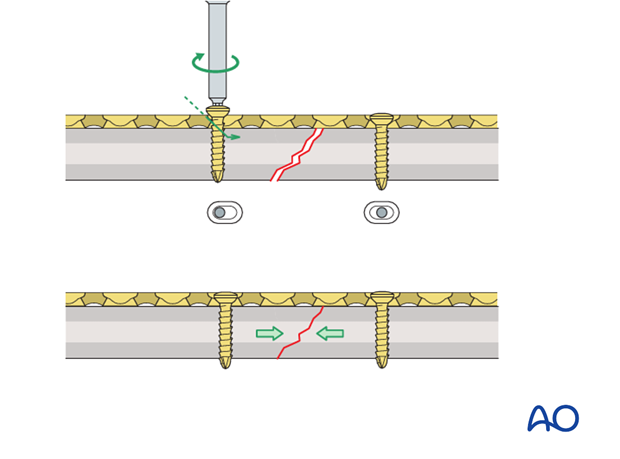

Compression plating

Axial compression results from eccentric screw (load screw) insertion with compression plates.

Plate position

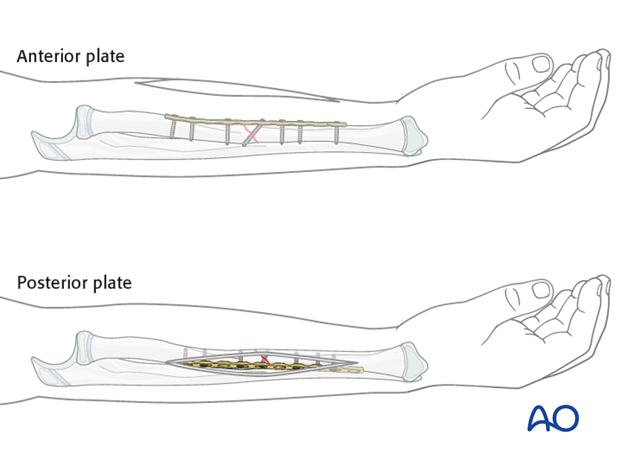

Depending on the surgical approach, the plate will be applied to either the anterior or posterior surface of the radius.

In the following example, a plate applied to the anterior surface is illustrated.

Make sure that the plate is seated on the bone without any soft-tissue interposition, apart from periosteum which should not be stripped.

In rare cases, the posterior interosseous nerve is visible. In such cases it is recommended that the position of the nerve in relationship to the plate be noted and documented in the operation report.

Choice of approach

For proximal radial shaft fractures, the anterior approach (Henry) is most often used to minimize the risk of damage to the posterior interosseous nerve, which crosses the proximal radius within the supinator.

In mid and distal radial shaft fractures, either the anterior approach (Henry) or posterolateral approach (Thompson) can be used, depending on surgeon’s preference.

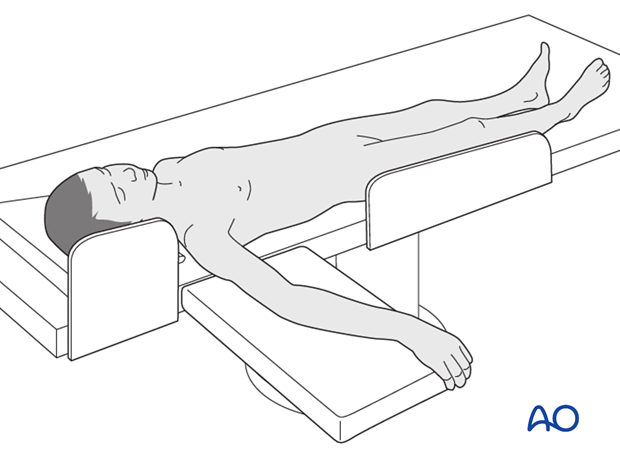

3. Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

4. Reduction

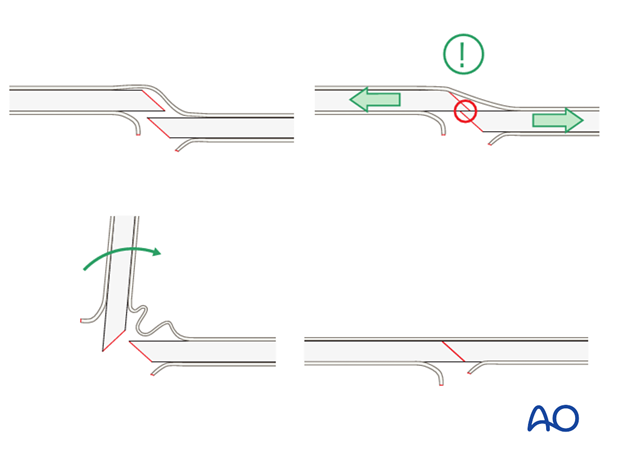

Reduction and fracture stability in children

Children’s periosteum is thick, tough tissue and is often intact on the concave (compression) side of a fracture.

Reduction maneuvers should be gentle to take advantage of the stability of the intact periosteum.

Exaggeration of the fracture deformity may be required to loosen the periosteum and allow for gentle reduction.

In pediatric fractures there is often a combination of patterns of bone failure. Residual plastic deformity may prevent anatomical reduction of some of the fracture edges. Provided the alignment of the bone is anatomical and overall reduction is stable it is not necessary to perfectly reduce the entire fracture.

Open reduction

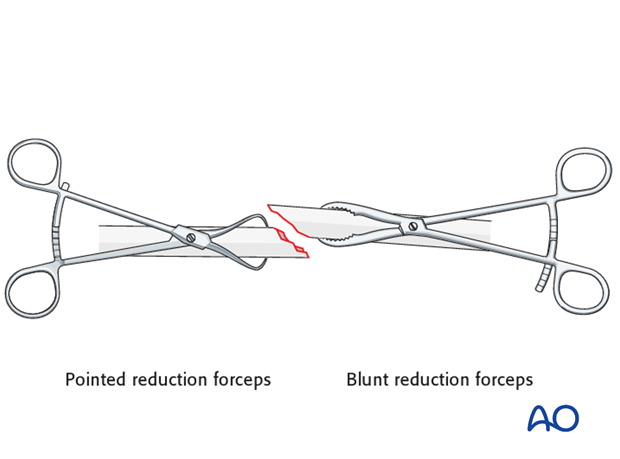

Reduce the fracture anatomically, using a reduction forceps on each main fragment.

The use of blunt, as opposed to pointed, reduction forceps can be helpful, particularly if greater forces are required.

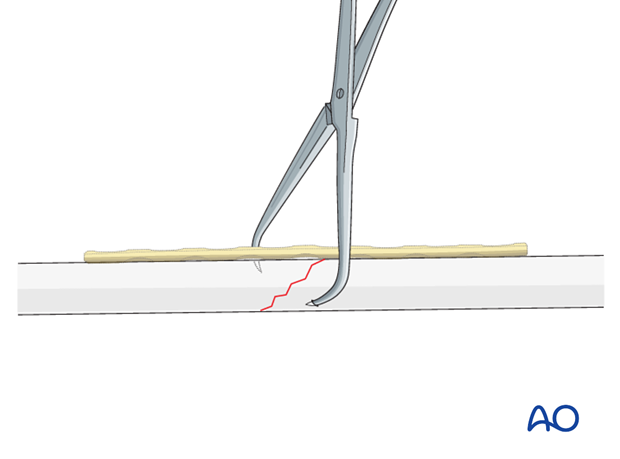

Pearl: twisting a reduction forceps

Reduction of overlapping oblique fractures can be achieved by twisting a reduction forceps, thereby lengthening the fracture.

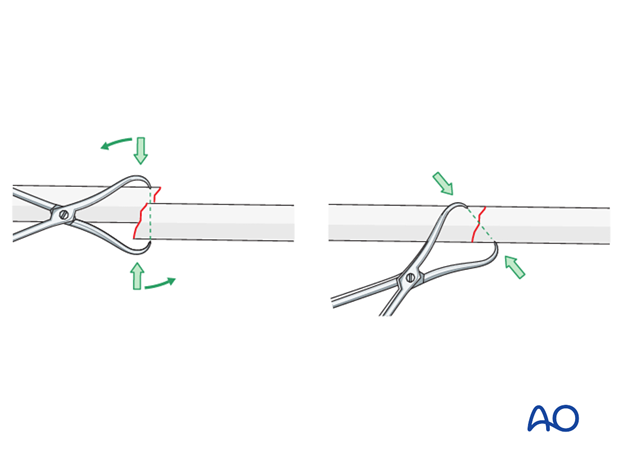

Maintaining fracture reduction

Maintain the fracture reduction with pointed reduction forceps.

Place the forceps such that it will not interfere with the planned plate position.

5. Plate length and number of screws

In the forearm, in addition to any lag screw, three bicortical plate screws are suggested in each main fracture fragment due to the high torsional stresses.

Not every plate hole needs to be occupied by a screw.

In oblique or spiral forearm shaft fractures an empty plate hole may be necessary at the level of the fracture to introduce a lag screw.

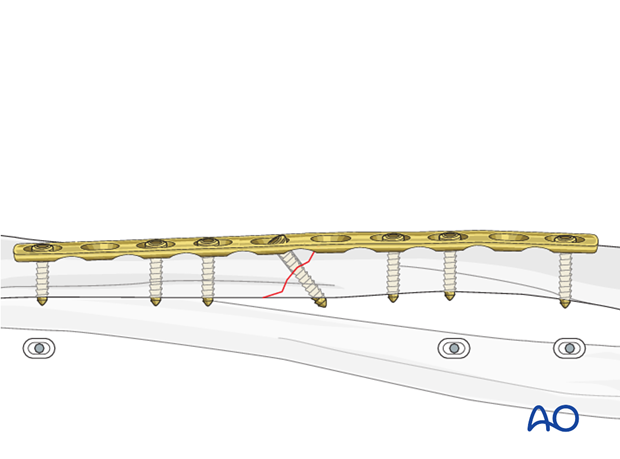

6. Fixation – lag screw as primary fixation device outside plate

Principle

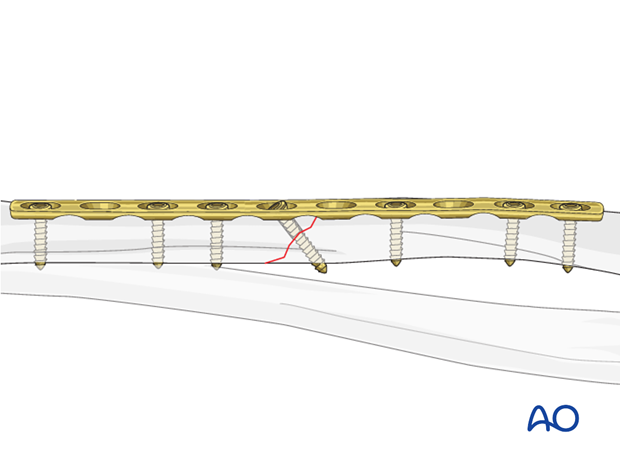

If the fracture morphology dictates that the interfragmentary lag screw be positioned separate from the plate, the plate then acts as a neutralization plate and axial compression should not be applied.

Insertion of lag screw

Insert a lag screw of appropriate length as perpendicular to the fracture plane as possible.

Maintain the reduction by leaving the pointed reduction forceps in situ.

Neutralization plate

To protect the primary lag screw fixation, apply a precisely contoured plate adjacent to the screw head without axial compression and all screws in the neutral position.

The pointed reduction forceps can then be removed.

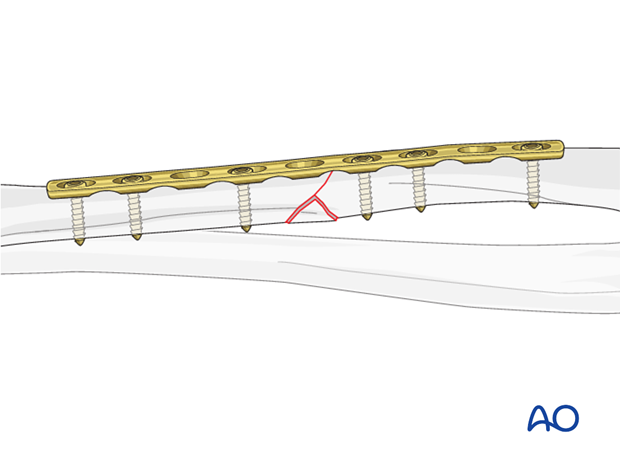

7. Fixation – lag screw as primary fixation device through plate

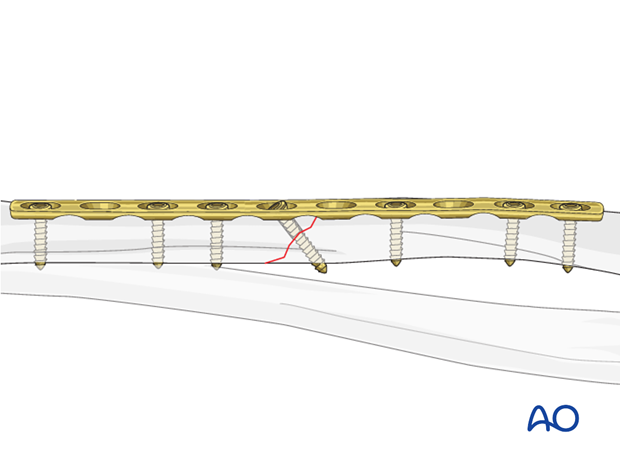

Principle

In some fracture configurations, it is advantageous to initially compress the fracture by inserting a lag screw through the relevant plate hole.

If this technique has been used, then axial compression must not be applied secondarily through the plate.

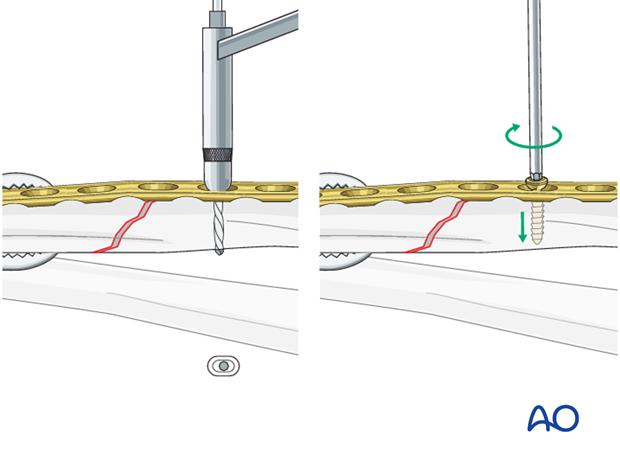

Insertion of lag screw through plate

Apply a precisely contoured plate to the surface of the anatomically reduced fracture and fix it to one main fragment, either with a neutral screw, or with a bone forceps as illustrated.

Then insert an interfragmentary lag screw through the appropriate plate hole as perpendicular to the fracture plane as possible.

Insertion of plate screws

Complete the fixation by inserting the plate screws in neutral mode, usually alternating between both main fragments.

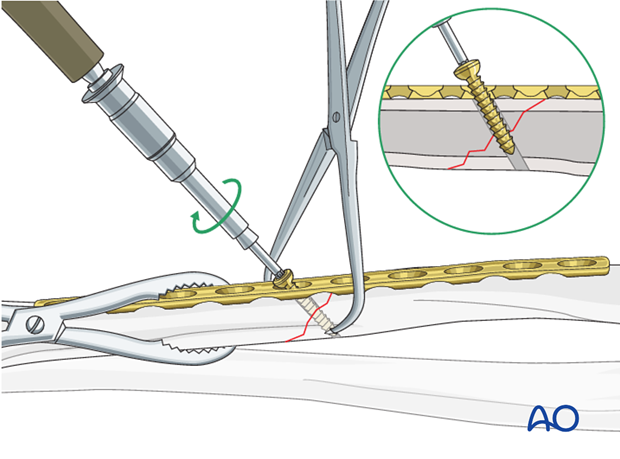

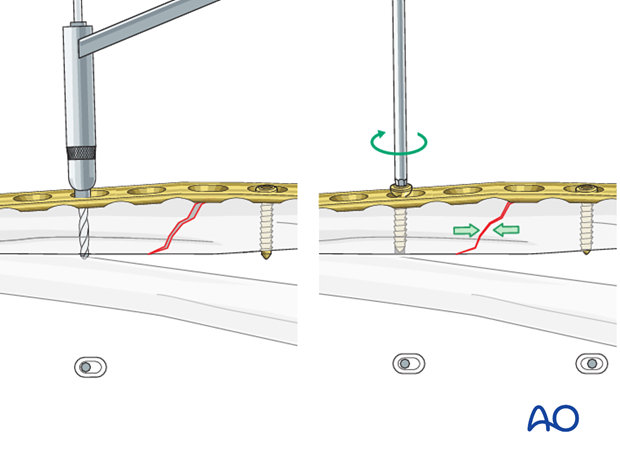

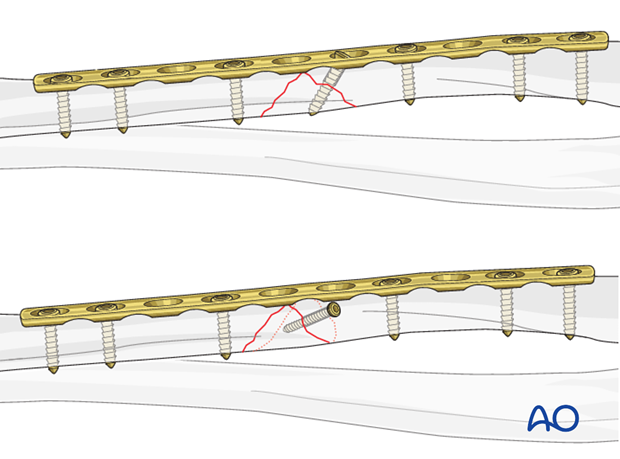

8. Fixation – compression plating with additional lag screw

Insertion of 1st screw

The aim of this maneuver is to create an “axilla” into which the other fragment can be compressed and locked either with a compression screw or using a push-pull technique.

Fix the plate to the appropriate fragment with a screw in neutral mode such that an axilla is created.

Place a reduction forceps on the opposite fragment to hold it in the reduced position against the plate.

Insertion of 2nd screw eccentrically

Insert a second screw eccentrically into the reduced fragment.

By tightening the eccentrically inserted screw, axial compression is achieved.

Insertion of lag screw

The stability of plate fixation in oblique fractures can be increased by inserting a lag screw through the plate after primary axial compression has been achieved.

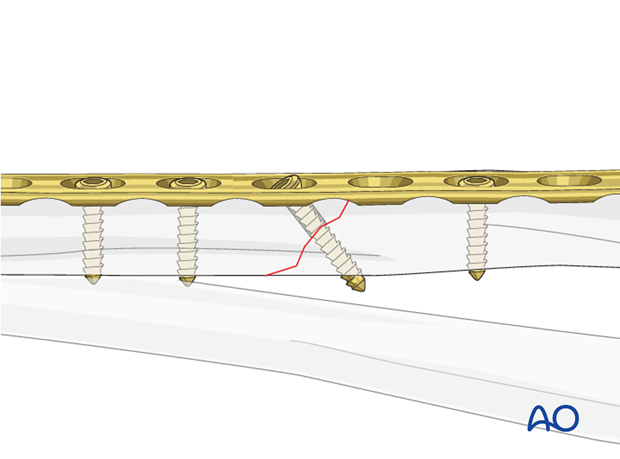

Completed osteosynthesis

Before inserting additional screws check reduction of the fracture and rotation of the forearm.

Additional screws in each fragment are inserted in a neutral position and do not produce additional compression.

9. Fixation of wedge fragments

Small wedge fragments

Small wedge fragments that do not have a significant effect on stability should not be addressed. They will become incorporated into the fracture by indirect bone healing.

The two main fragments will be fixed with plating.

Large wedge fragments

Larger wedge fragments, that contribute to the stability of the fixation, may be fixed to one main fragment.

Fixation of the wedge to one main fragment may assist reduction of the residual fragment.

The two main fragments will then be fixed with compression plating either with the lag screw through the plate or separate to the plate.

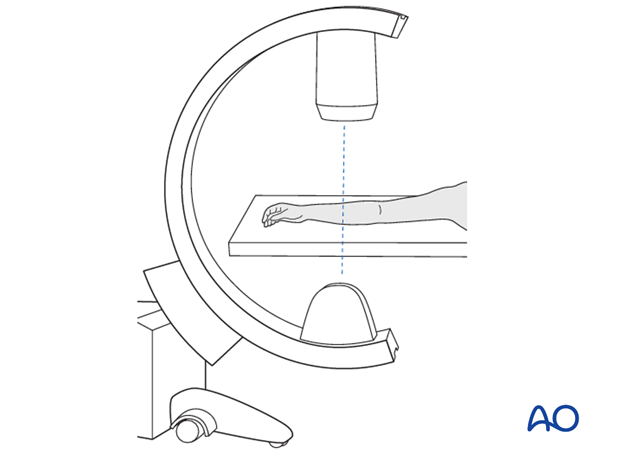

10. Final assessment

Check the completed osteosynthesis with image intensification. These images should be retained for documentation or alternatively an x-ray should be obtained before discharge.

Make sure that the plate is at the correct location, the screws are of appropriate length and the desired reduction has been achieved.

Stabilize the elbow at the epicondyles and check the forearm rotation.

11. Aftercare following plating

Immediate postoperative care

Whilst the child remains in bed, the forearm should be elevated on pillows to reduce swelling and pain.

Casting or Splinting

Plate fixation of forearm fractures is intrinsically stable and supplementary casting or splinting is therefore not required.

Some surgeons prefer a long or short splint for 2-3 weeks postoperatively for comfort.

Analgesia

Ibuprofen and paracetamol should be administered regularly during the first 4-5 days of injury, with additional oral narcotic medication for breakthrough pain.

If the level of pain is increasing the child should be examined.

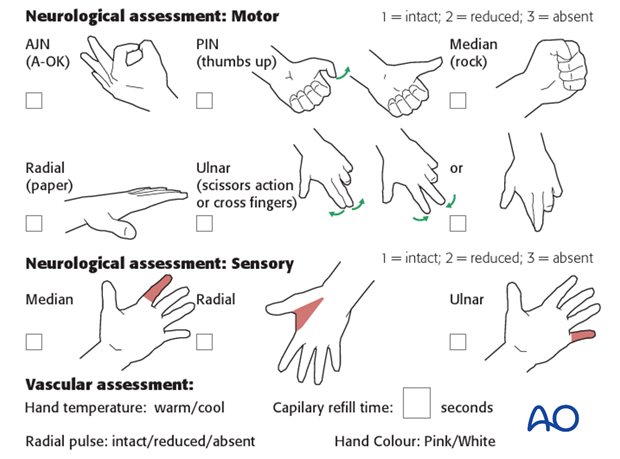

Neurovascular examination

The child should be examined regularly, to ensure finger range of motion is comfortable and adequate.

Neurological and vascular examination should also be performed.

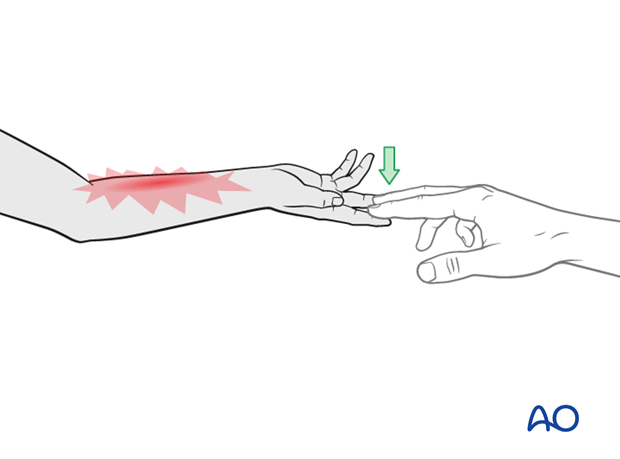

Compartment syndrome should be considered in the presence of increasing pain, especially pain on passive stretching of muscles, decreasing range of active finger motion or deteriorating neurovascular signs, which are a late phenomenon.

See also the additional material on postoperative infection.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a possible early postoperative complication that may be difficult to diagnose in younger children.

The presence of full passive or active finger extension, without discomfort, excludes muscle compartment ischemia.

If there are signs of a compartment syndrome:

- If the child is in a cast, split the cast, along its full length down to skin level.

- Elevate the limb.

- Encourage active finger movement.

- Reexamine the child after 30 min.

If a definitive diagnosis of compartment syndrome is made, then a fasciotomy should be performed without delay.

Discharge care

Discharge from hospital follows local practice and is usually possible after 1-3 days.

The parent/carer should be taught how to assess the limb.

They should also be advised to return if there is increased pain or decreased range of finger movement.

It is important to provide parents with the following additional information:

- The warning signs of compartment syndrome, circulatory problems and neurological deterioration

- Hospital telephone number

- Information brochure

For the first few days, the elbow and forearm can be elevated on a pillow, until swelling decreases and comfort returns.

The arm can be placed in a sling for a few days until the patient is pain free. Many children are more comfortable without support.

Mobilization

Early movement of the forearm should be encouraged as soon as the patient is pain free.

Formal physiotherapy is normally not indicated, but children should have a sheet of exercises to stimulate mobilization.

Follow-up

The first clinical and radiological follow-up depends on the age of the child and is usually undertaken 4 weeks postoperatively.

At this point, the child should be able to move the forearm almost fully.

AP and lateral x-rays are required.

See also the additional material on healing times.

Plate removal

Plate removal is delayed for at least 6 months.

An asymptomatic plate that does not interfere with forearm rotation can be left in place minimizing complications associated with implant removal.