ORIF - Compression plate

1. General considerations

Principles

This fracture requires anatomical reduction and interfragmentary compression. Exposure for direct reduction is often necessary. This involves a longer incision than MIO technique. Care is taken to minimize periosteal disruption.

The soft-tissue envelope dictates the choice and timing of the procedure: early single-stage or multiple-stage surgery.

Displaced fractures with minimal, closed soft-tissue injury

(Tscherne classification, closed fracture grade 0, rarely grade 1)

These injuries may be reduced and fixed primarily, as a single stage procedure, if the soft tissues are in truly excellent condition.

A distractor or external fixator may aid reduction. Fibular reduction and fixation is the usual next step, but this reduction must be accurate, so that it does not prevent tibial reduction. Finally, the tibial plate is introduced, and final reduction of length, alignment and rotation is achieved.

Grossly displaced fractures and/or fractures with severe, closed soft-tissue injury

(Tscherne classification, closed fracture grade 2 or 3)

It is generally advisable to proceed in two or more stages:

- Closed reduction and joint bridging external fixation

- Definitive MIO reconstruction after 5-10 days (wait for the appearance of skin wrinkles)

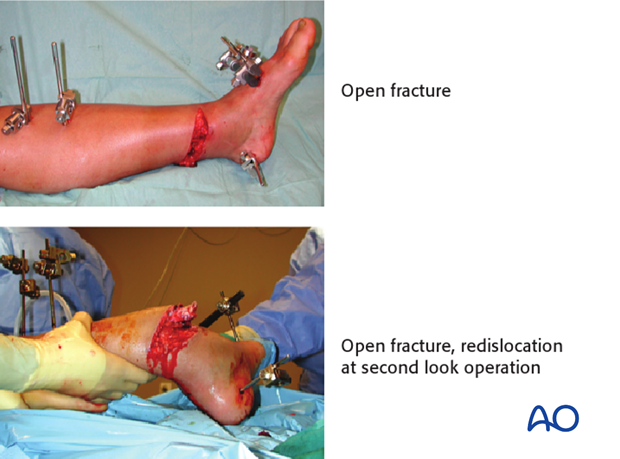

Open distal tibial fractures

Simple fracture patterns in the setting of significant open wounds can be managed by meticulous debridement and acute compression plate fixation.

Typically, definitive fracture stabilization should be delayed until the time of definitive soft tissue coverage. This management includes several stages:

- Emergency management: Wound debridement and lavage. Joint-bridging external fixation and stabilization of the fibula (if needed and soft tissues allow). Where possible, closure or coverage of any opening into the joint should be achieved

- After 48 hours: Plan soft-tissue coverage (local or free flap)

- Definitive stabilization at the time of soft-tissue coverage

2. Fibula or tibia first? Sequence of bone stabilization

Introduction

If the fibula is fractured, it usually needs to be stabilized.

Simple fibular fractures

This fracture is usually addressed as first step by open anatomic reduction and plate fixation. Alternatively, for transverse fractures, a small diameter, flexible intramedullary nail may be considered. Fibular reduction helps realign the tibia fracture.

Multifragmentary fractures of the fibula

Reduction in this case may be difficult. Malreduction of the fibula will impede anatomic reconstruction of the tibia. In this situation, fibular ORIF is better performed after the tibia has been fixed. The syndesmotic ligaments are usually intact, so gross realignment of the fibula occurs with reduction and fixation of the tibia. For comminuted fibular fractures a MIO technique with a long bridging plate, or intramedullary fixation of the fibula with a small diameter, flexible nail is easily achieved after tibial reduction and fixation. Fibular nailing is particularly applicable if the soft-tissue injury or complexity of the fracture makes extensive exposure for internal fixation hazardous.

3. Preoperative planning

Planning for reduction and fixation

Two-part fractures should be treated with absolute stability achieved by anatomic reduction and interfragmentary compression. This will require lag screw fixation and/or plate tensioning, depending upon the fracture orientation. Typically, a limited open reduction will be required, with fracture exposure for reduction and subcutaneous plate application proximally.

Proper contouring and positioning of the plate is essential for optimal reduction. Both are aided by preoperative planning.

Preoperative planning consists of:

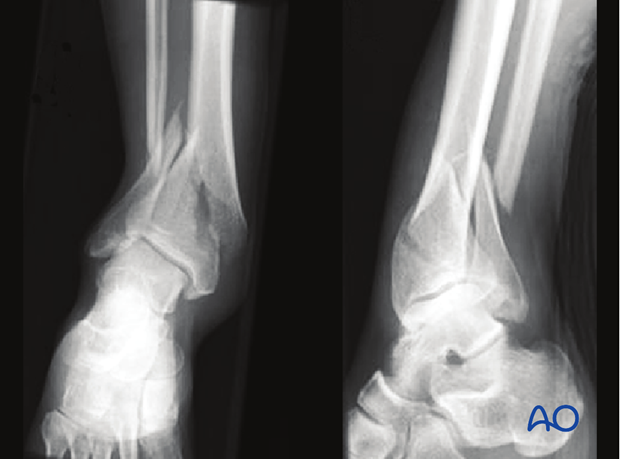

- Obtain good AP and lateral x-rays of both injured and uninjured side; CT if needed

- Careful study of the x-rays and CT

- Trace AP and lateral x-rays of normal side

- Identify the individual fracture fragments

- Draw the fracture fragments, reduced, onto the normal tracing

- Consider reduction techniques

- Choose and draw in fixation implants

- Choice of surgical approach

- Prepare list of operative steps

4. Patient preparation and approaches

Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

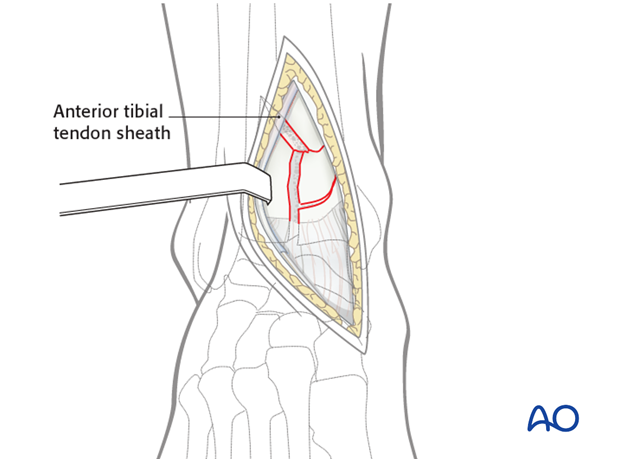

Anteromedial approach

The anteromedial approach is used for open reduction and internal fixation of the articular part of the tibia. It facilitates accurate articular reduction combined with submuscular and subcutaneous plate applications.

Anterolateral approach

The anterolateral approach is useful in the majority of complete articular pilon fractures, anterior and anterolateral partial articular pilon fractures, and some extraarticular distal tibia fractures.

5. Implant choice and plate preparation

Implant choice

Precontoured distal tibial plates will provide more options for distal fixation and are preferred.

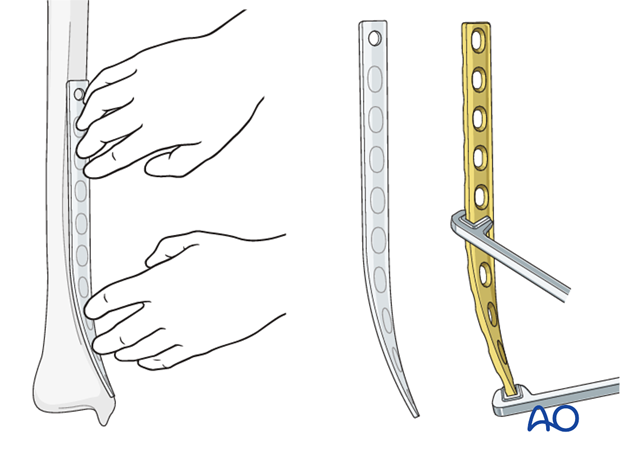

Plate contouring

If precontoured implants are not available a non-contoured plate can be shaped prior to sterilization, using a sawbones model as a template.

Determine the length of the plate from preoperative x-rays. It should be placed as distally as possible and long enough to place at least four holes proximal to the fracture (with screws in at least three of them).

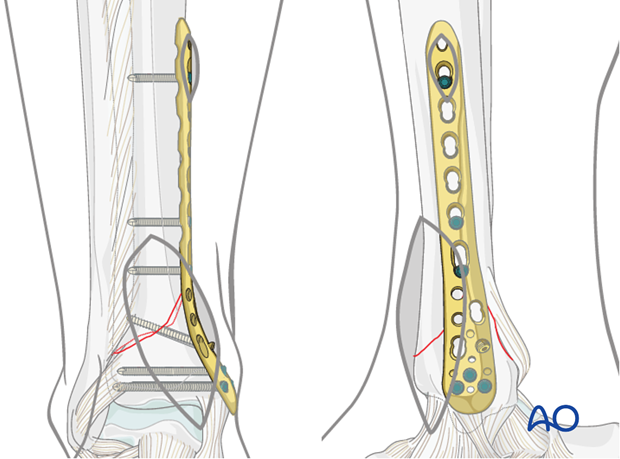

The most distal 8-12 cm of the plate must be bent to form a concave arc with a radius of curvature of about 20 cm and twisted to fit the distal tibia. As illustrated, the medial tibia is internally rotated distally (20 degrees) and lies closer to the sagittal plane.

With ORIF of simple tibia fractures, enough of the tibial surface may be exposed to aid and assess plate contouring.

6. Reduction

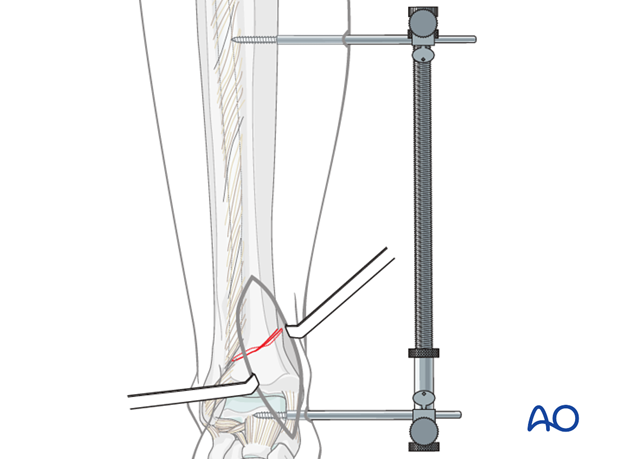

Indirect reduction with a femoral distractor

An appropriately positioned “femoral” distractor or external fixator is usually not necessary, but it can be very helpful in delayed presentation with significant shortening.

Medial positioning allows subcutaneous access to the tibia. A laterally based distractor requires a pin through the anterior muscular compartment but provides more efficient distraction of any associated fibular fracture, and correction of valgus deformities. Distraction can be used for the open reduction and plate fixation of the fibula as first step (if not already fixed) and for the reduction of the tibia as a second stage following fibular stabilization.

Schanz screws are positioned in safe zones of the tibial shaft and talar neck (or the tuber calcanei). In case of previously applied joint-bridging fixation, the already existing Schanz screws can be used.

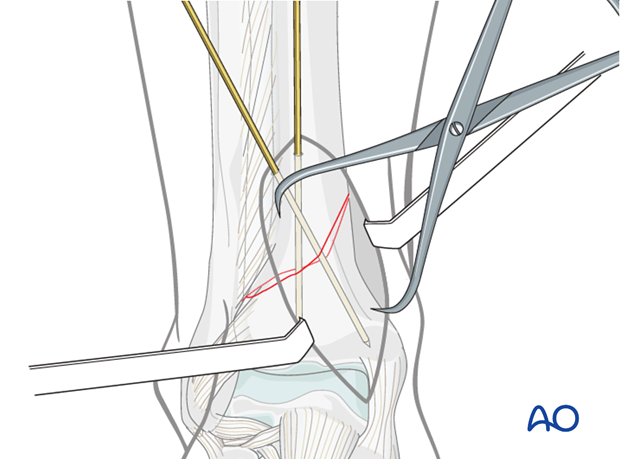

Direct reduction

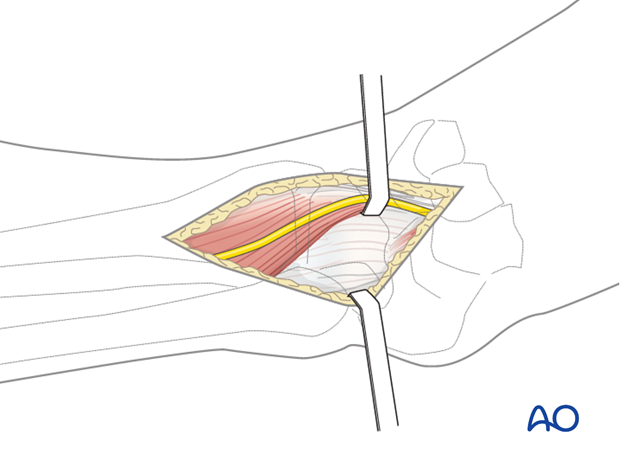

Once visualization is adequate, the fracture can be reduced directly using one or two pointed reduction clamps.

During reduction, soft-tissue attachments should be preserved to the greatest extent possible.

The reduction is provisionally secured with K-wires, and the clamp can be removed for plate insertion.

Note: K-wires should not interfere with planned plate and screw position. See also the content on assessment of reduction.

7. Plate insertion and preliminary stabilization

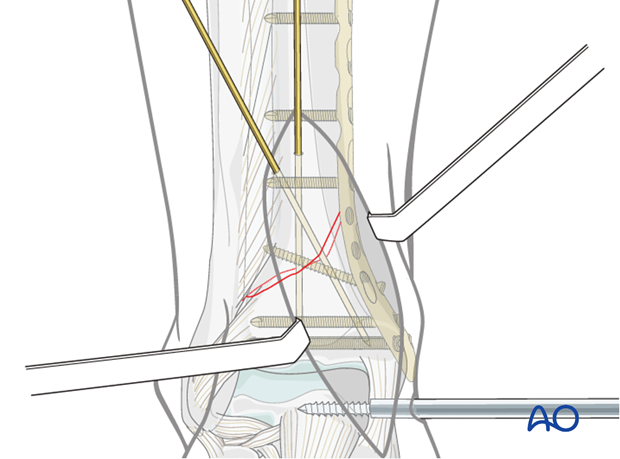

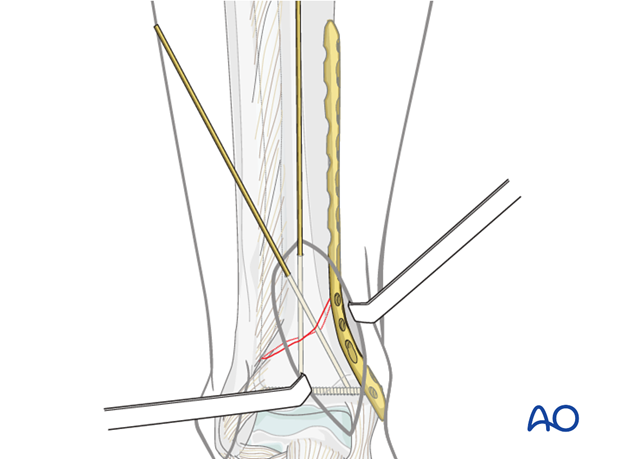

Insertion of the plate

The prepared plate is inserted from distally through the existing incision. Proximally, the plate may be tunneled extraperiosteally along the tibia, under intact soft tissues.

Depending on the fracture anatomy, the plate is usually positioned on the anteromedial aspect, or seldom, on the anterior crest of the tibia.

Preliminary plate stabilization

Once accurate position of the plate has been achieved, a conventional screw is inserted in one of the most distal plate holes and fixed.

Alternatively, the plate can be manually pressed to the bone, allowing the insertion of a locking head screw instead of the conventional screw.

It is crucial that the plate is positioned close to the bone, at the supramalleolar level, to prevent soft-tissue irritation by the plate.

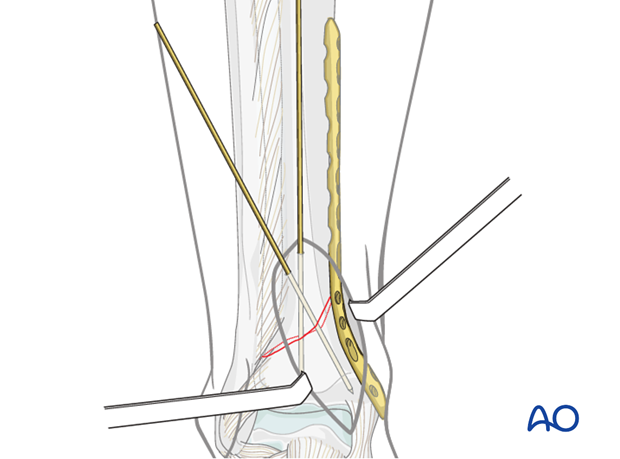

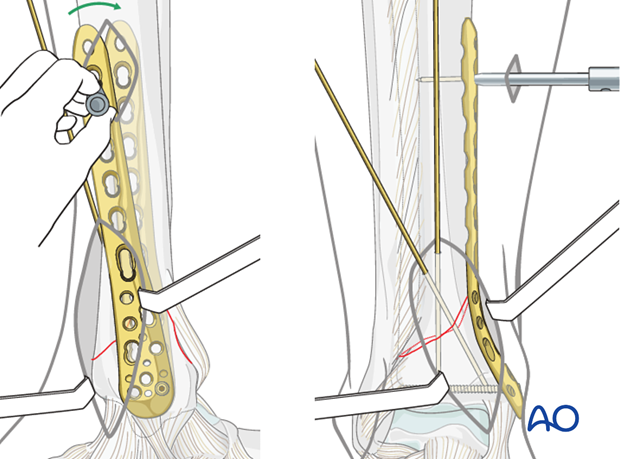

Proximal plate position

The proximal end of the plate must be positioned in the center of the diaphysis. This can be done either by formal exposure of the plate end by a wider approach or using an insert drill sleeve in the most proximal plate hole through a stab incision.

The drill sleeve can be used as a handle to manipulate the proximal end of the plate and to center it to the diaphysis. As soon as adequate position is confirmed (by palpation of the diaphysis or using fluoroscopic control), the plate can preliminarily be fixed proximally by inserting a K-wire.

8. Applying compression

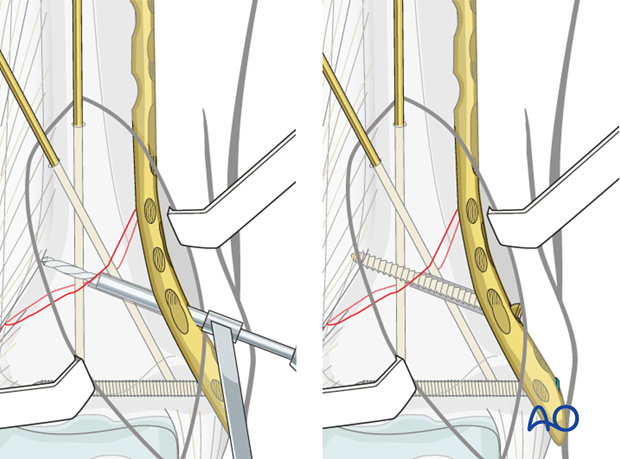

Interfragmentary compression with a lag screw

For short oblique and spiral fracture patterns the goal is to achieve perfect reduction and compression with a lag screw either through the plate or separate to it. See also the content on assessment of reduction.

Compression with plate tension

For transverse fractures it is necessary to add a subtle convex prebend to the implant at the fracture level (to ensure that the opposite side of the fracture remains compressed),

Additional distal screws are inserted.

Fracture compression is achieved by applying tension with the plate, using eccentric placement of screws in non-locked holes, or an external tension device.

See also the content on assessment of reduction.

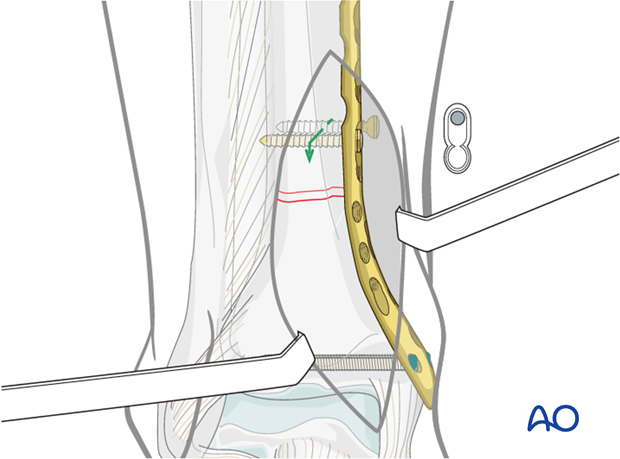

9. Definitive plate fixation

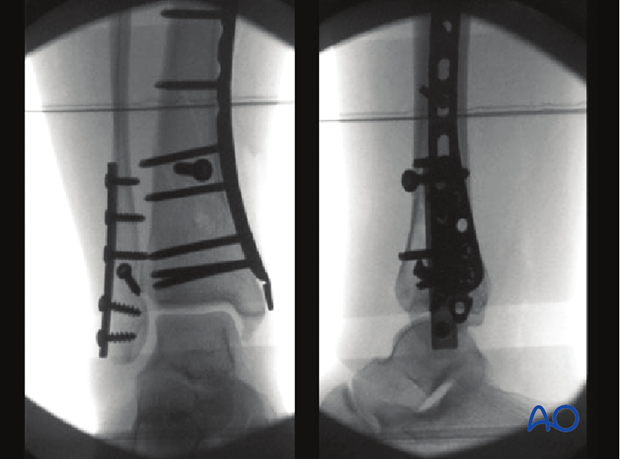

Once the preliminary fixation and reduction are satisfactory, additional screws are added for stability.

The number and position of the screws inserted depends on the specific fracture pattern. The goal is “balanced fixation”. This means roughly equivalent fixation strength in both proximal and distal segments. Usually, the metaphysis requires more screws (3-5) than the diaphysis (2-3). Cortical bone provides better screw purchase than cancellous.

In osteoporotic bone, the number of screws should be increased, particularly in the cancellous distal segment.

Wound closure

Close the wound in layers over the plate and fracture. Skin sutures alone are sufficient for proximal screw incisions. A suction drain is optional.

10. Final assessment

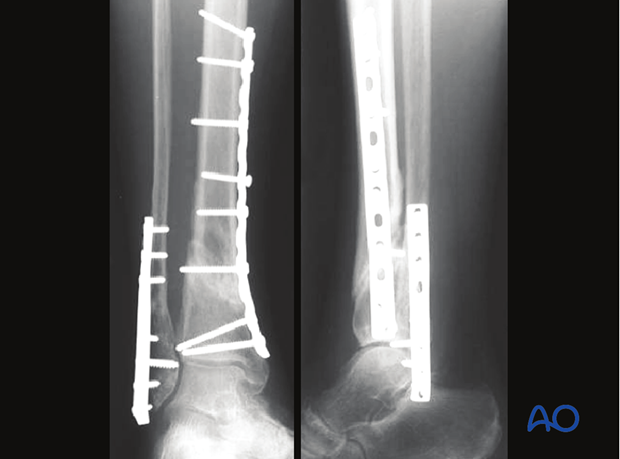

The x-ray imaging at the end of the operation confirms the anatomical restoration of length, alignment and rotation (see also the content on assessment of reduction).

It is important to check with imaging in both planes that a previously unrecognized split into the articular surface has not been displaced during this procedure. Additional fixation of such a fracture line may be required.

11. Aftercare following plating

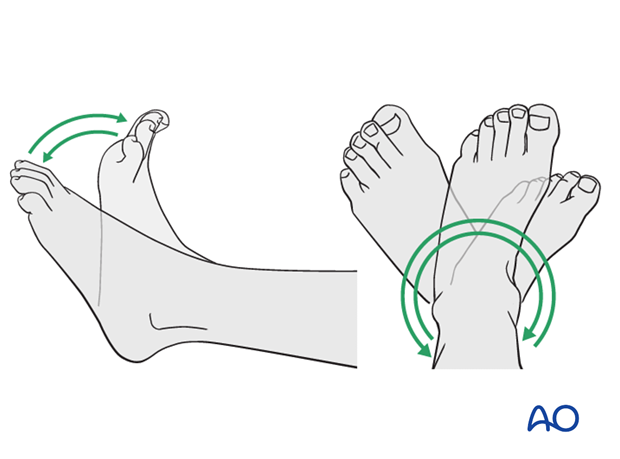

Leg elevation is recommended for the first 2-5 postoperative days. Physiotherapy with active assisted exercises is started immediately after operation. Immobilization is not necessary.

Mobilization

Starts depending on the wound healing with flat footed, weight of the leg weight bearing (10-20kg).

Follow up

Clinical and radiological follow-up is recommended after 2, 6 and 12 weeks. Depending on the consolidation, weight bearing can be increased after 6-8 weeks with full weight bearing usually after 3 months. Supervised rehabilitation with intermittent clinical and radiographic follow-up is advisable every 6-12 weeks until recovery reaches a plateau, typically 6-12 months after injury. Weight-bearing radiographs are preferable to assess articular cartilage thickness. Angular stable fixation may obscure signs of non-union for many months.

Implant removal

Implant removal may be necessary in cases of soft-tissue irritation by the implant (plate and/or isolated screws). The best time for implant removal is after complete remodeling, usually at least 12 months after surgery.