ORIF - Screw fixation

1. General considerations

Introduction

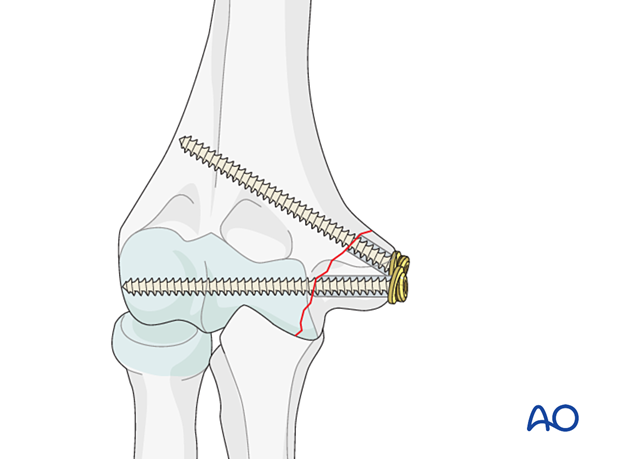

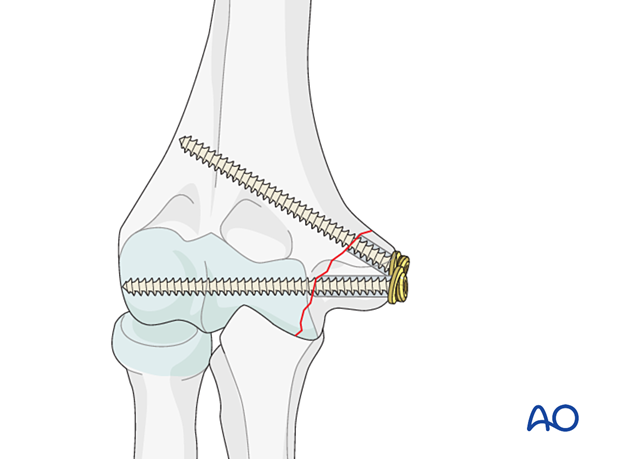

The fragment is stabilized with two screws to provide sufficient fixation.

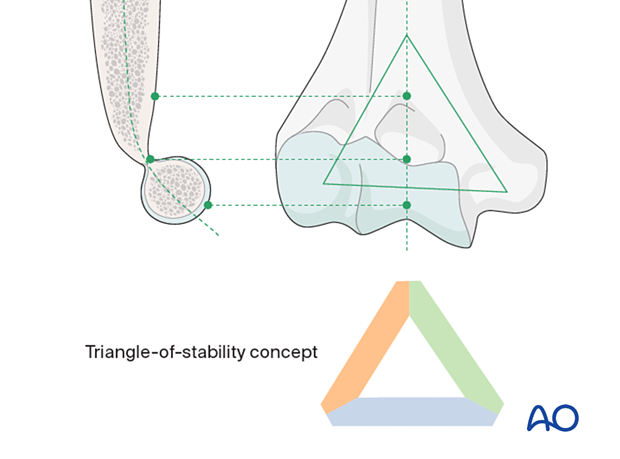

Triangle-of-stability concept

The mechanical properties of the distal humerus are based on a triangle of stability, comprising the medial and lateral columns and the articular block (see also the anatomical concepts).

Screw selection

The choice between standard screw fixation and cannulated screw fixation is usually dependent on the surgeon’s individual preferences, the equipment available, and the operative and imaging facilities.

The application of noncannulated screws is described in this procedure.

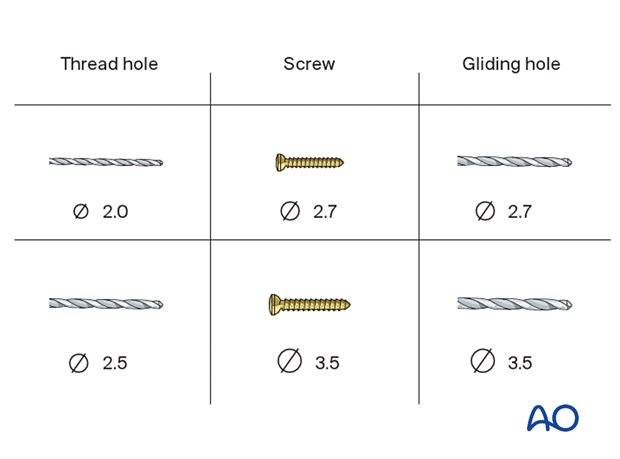

Depending on the size of the fracture fragment and patient characteristics, 2.7 and 3.5 mm screws are most commonly used.

Noncannulated screw technique

If the bone fragment is large enough to accommodate a screw and a K-wire, the provisional reduction should be held with K-wires placed in a position that will not interfere with definitive screw fixation.

If the fragments are too small, the reduction and provisional fixation should be held with K-wires, which are then exchanged carefully, one at a time, for the definitive screws.

2. Patient preparation and approach

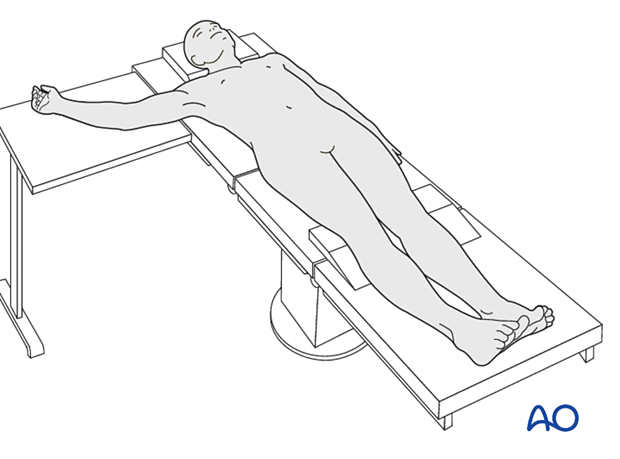

Patient positioning

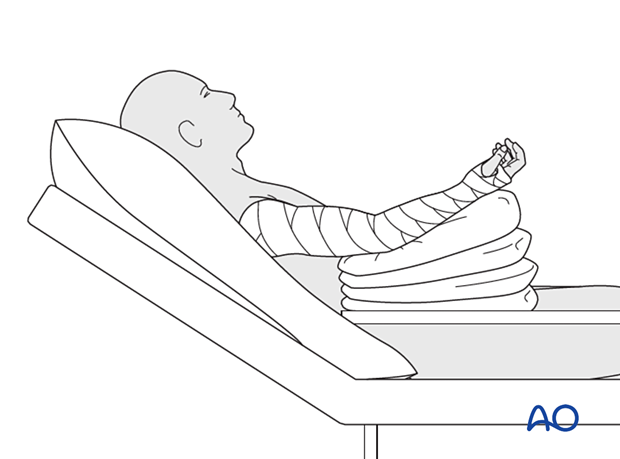

This procedure is usually performed with the patient in a supine position.

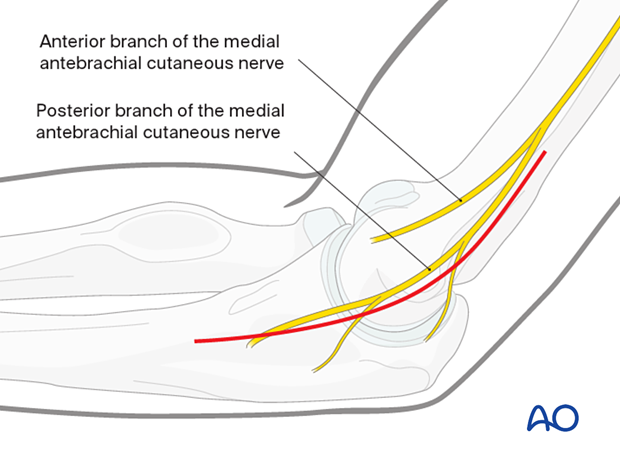

Approach

The preferred approach is the direct medial approach. This provides access to the ulnar nerve, the medial fracture fragment, and the ulnohumeral joint.

3. Open reduction

Mobilizing the fragment

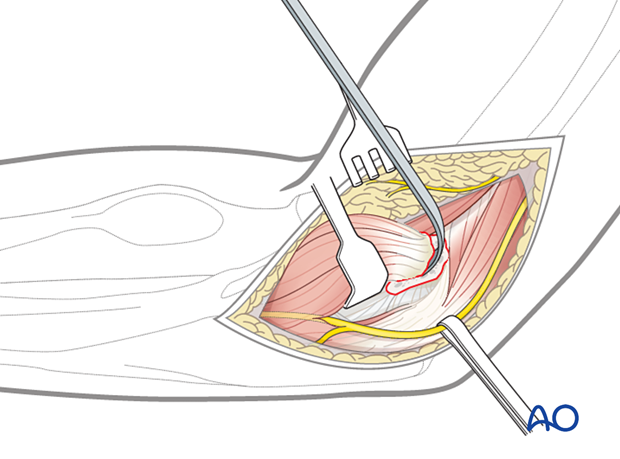

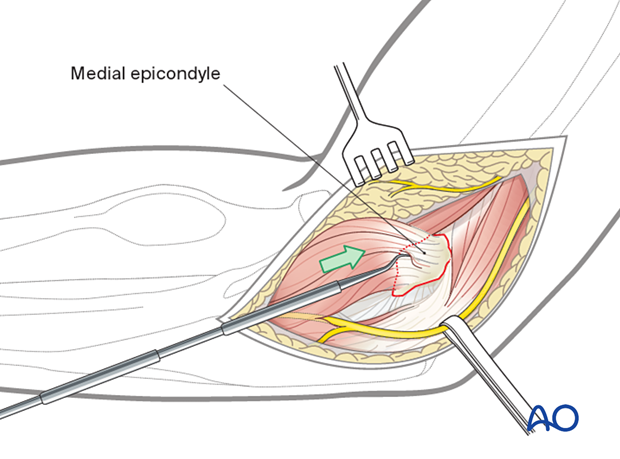

Identify and protect the ulnar nerve (see also neurological protection and handling).

Open the fracture site by gently retracting the fragment anteriorly.

Clearing the fracture site

Clear the fracture of any hematoma, loose pieces of bone, or interposed tissue.

Inspect the joint surfaces to ensure that there is no additional intraarticular fracture extension.

Reduction

Align the fracture and maintain reduction with a small hook or pick.

Monitor fracture reduction by realigning the metaphyseal fracture lines.

Depending on the extent of exposure, check the anterior and posterior fracture lines, including the articular surface.

4. Provisional fixation

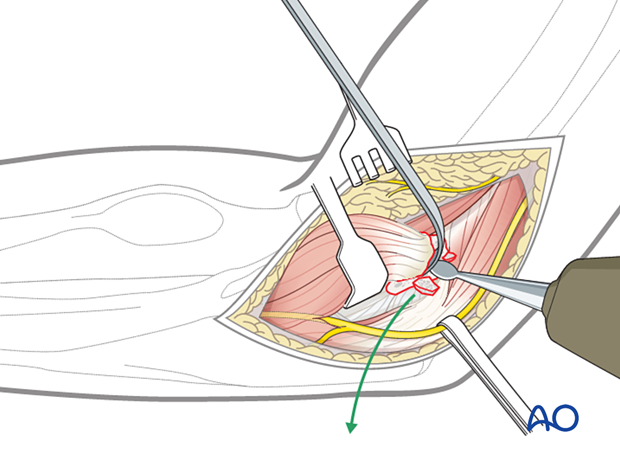

Planning for screws

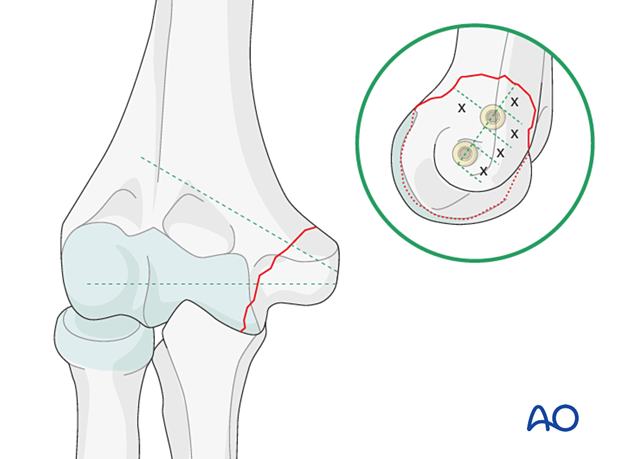

The screws must avoid the olecranon fossa and the articular surface. Generally, there is space for one screw through the articular condylar mass and one screw through the opposite cortex.

Insertion of K-wires

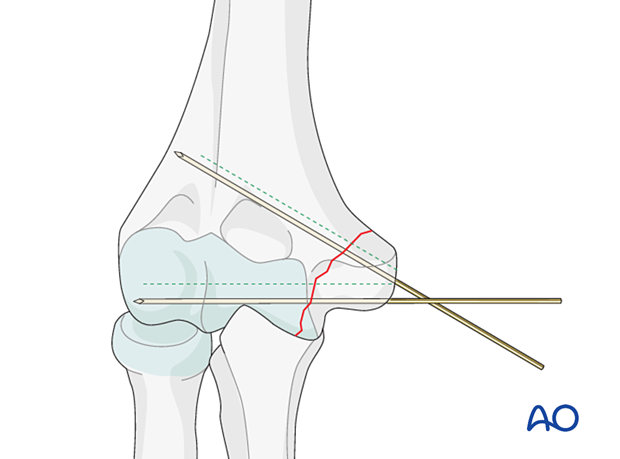

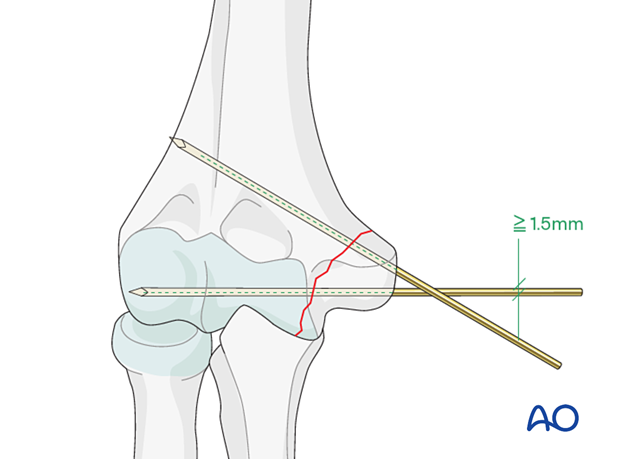

Secure the reduction with two or more K-wires crossing the fracture site. Take care to avoid the planned screw tracks.

Use smooth K-wires at least 1.6 mm in diameter.

Check fracture alignment and K-wire position with image intensification.

Alternative K-wire placement

Alternatively, use a K-wire the size of the drill and place the K-wires in the planned screw tracks.

Using this technique, each wire can be exchanged for its screw, skipping the drilling step.

5. Drilling

Principle

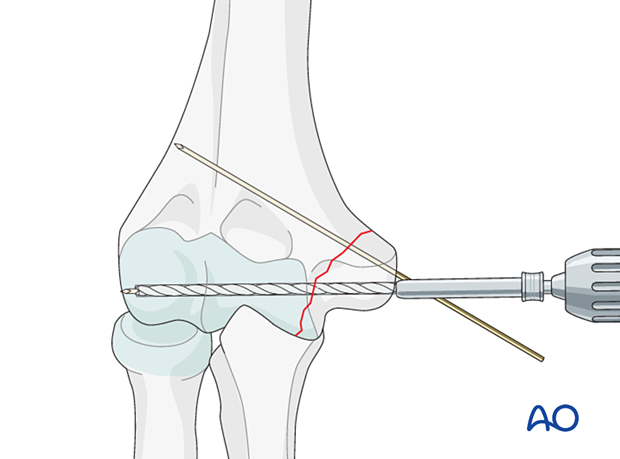

Complete the entire sequence of drilling and screw insertion for each screw before inserting the next screw.

Usually, the first screw is inserted in the articular block.

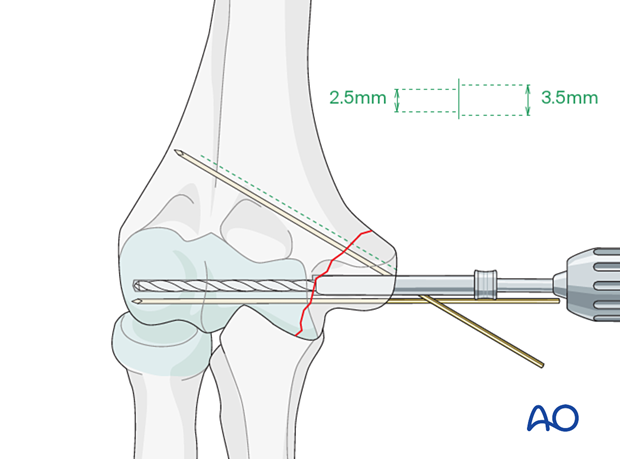

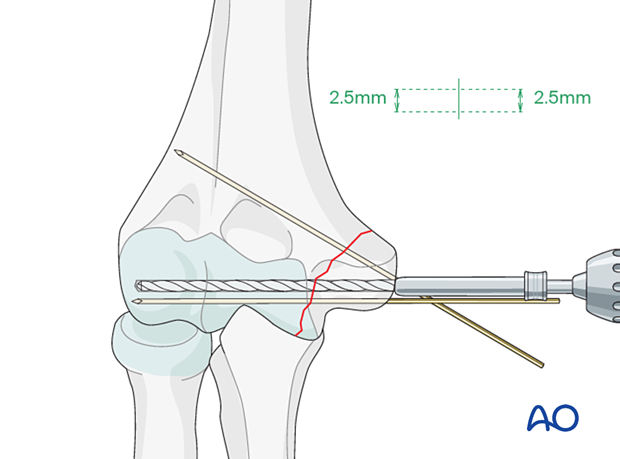

Lag- and position-screw technique

For the lag screw technique using a fully threaded screw (3.5/2.7 mm), drill the near fragment with the appropriate thread-diameter drill to create a gliding hole and the far fragment with an appropriate core-diameter drill.

Be careful using the lag screw technique in metaphyseal bone, particularly when osteoporotic. It may be preferable to use a position screw technique in which thread purchase is obtained in both the near and far fragments.

Alternative: partially threaded screw technique

For a partially threaded 4.0 mm cancellous screw, drill both fragments with a 2.5 mm drill.

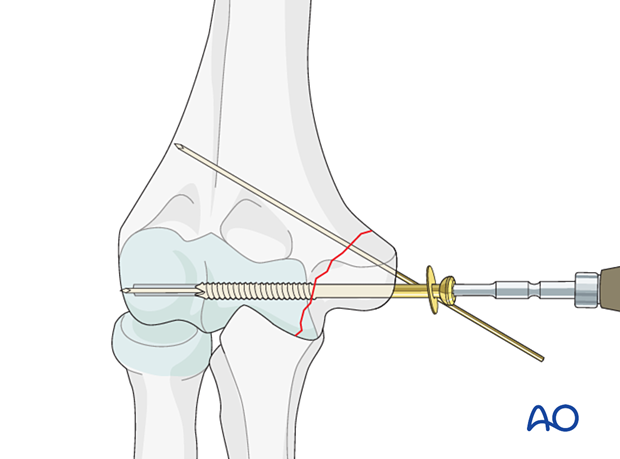

Alternative: cannulated screw technique

In this technique, the K-wires are used as a guide wire for the cannulated screws.

Compression is usually achieved with a partially threaded screw.

6. Definitive fixation

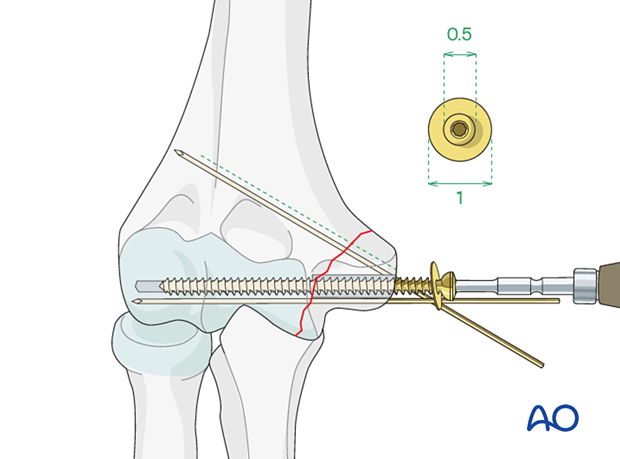

Screw insertion

Insert the screw.

It may be helpful to use a washer with the screw to avoid fragment splitting and incorporate the soft-tissue structures.

Alternative: insertion of cannulated screws

Advance the screw over the guide wire.

Once the screw is inserted, remove the wire.

Insertion of further screws

Insert a second screw.

Remove provisional K-wires.

7. Final assessment

Visually inspect the fixation and manually check for fracture stability.

Repeat the manual check under image intensification.

8. Aftercare

Introduction

The rehabilitation protocol consists usually of three phases:

- Rehabilitation until wound healing

- Rehabilitation until bone healing

- Functional rehabilitation after bone healing

Immediate aftercare

The arm is bandaged to support and protect the surgical wound.

The arm is rested on pillows in slight flexion of the elbow so that the hand is positioned above the level of the heart.

Short-term splinting may be applied for soft-tissue support.

Neurovascular observations are made frequently.

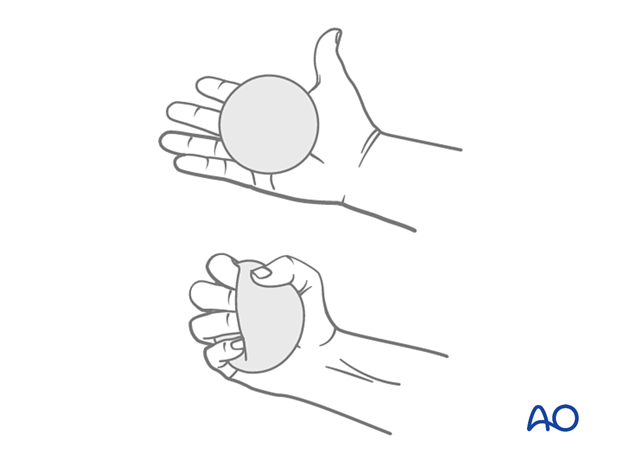

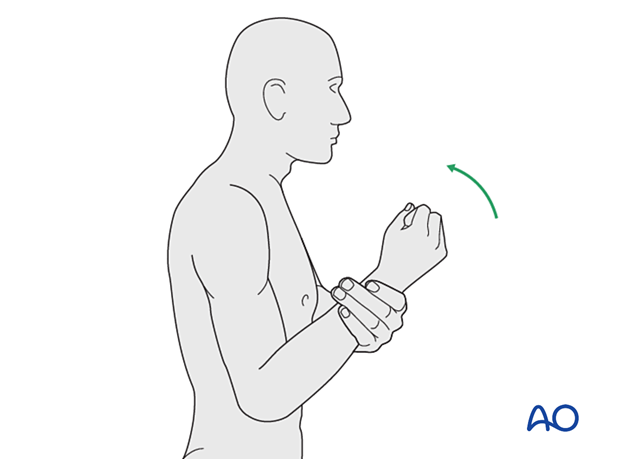

Hand pumping and forearm rotation exercises are started as soon as possible to reduce lymphedema and to improve venous return in the limb. This helps to reduce postoperative swelling.

Mobilization until wound healing

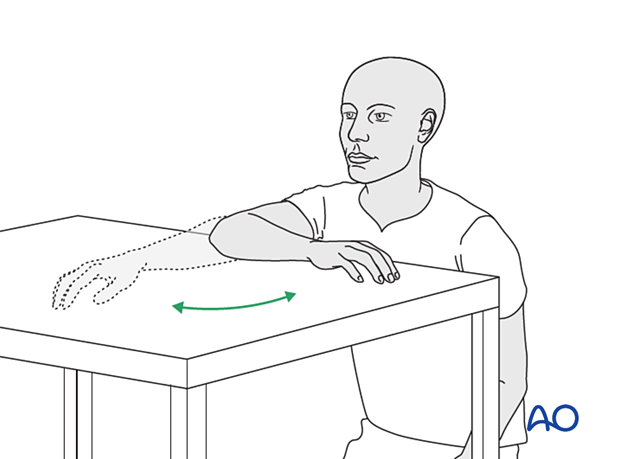

Gravity-eliminated active assisted exercises of the elbow should be initiated as soon as possible, as the elbow is prone to stiffness:

- The bandages are removed, and the arm rested on a side table

- Flexion/extension of the arm at the elbow is encouraged in a gentle sweeping movement on the tabletop as far as comfort permits (as illustrated)

- Full pronation and supination in protected arm position is encouraged

- Exercises are performed hourly in repetitions, the number of which is governed by comfort

- Between periods of exercise, the elbow is rested in the elevated position for at least the first 48 hours postoperatively

- Keep the arm elevated between periods of exercise until the wound has healed

Rehabilitation until bone healing

Active patient-directed range-of -motion exercises should be encouraged without the routine use of splintage or immobilization.

Avoid forceful motion, repetitive loading, or weight-bearing through the arm.

A simple compressive sleeve can provide proprioceptive feedback which can help regain motion and avoid cocontraction.

No load-bearing (ie, pushing, pulling, or carrying weights) or strengthening exercises are allowed until early fracture healing is established by x-ray and clinical examination.

This is usually a minimum of 8–12 weeks after injury. Weight-bearing on the arm should be avoided until bony union is assured.

The patient should avoid resisted extension activities, especially after a triceps-elevating approach or olecranon osteotomy.

Rehabilitation after bone healing

When the fracture has united, a combination of active functional motion and kinetic chain rehabilitation can be initiated.

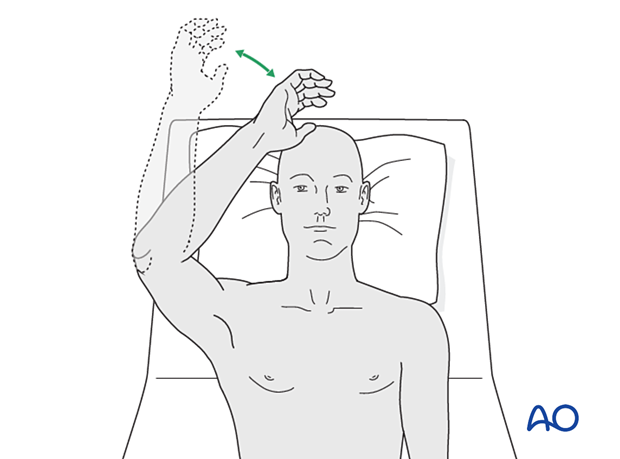

Active assisted elbow motion exercises are continued. The patient bends the elbow as much as possible using his/her muscles while simultaneously using the opposite arm to gently push the arm into further flexion. This effort should be sustained for several minutes; the longer, the better.

Next, a similar exercise is performed for extension.

If the patient finds it difficult to accomplish these exercises when seated, then performing the same exercises when lying supine can be helpful.

Implant removal

Generally, the implants are not removed. If symptomatic, hardware removal may be considered after consolidated bony healing, usually no less than 6 months for metaphyseal fractures and 12 months when the diaphysis is involved. The avoidance of the risk of refracture requires activity limitation for some months after implant removal.