Open reduction with fixation

1. Principles

Open treatment can be considered if the isolated zygomatic arch deformity is so severe that it cannot be adequately treated with a transoral (Keen) or temporal (Gillies) approach, or if it is too unstable to be treated without fixation. This has the advantage of allowing direct visualization of the zygomatic arch for fixation. It may be particularly desirable in a patient where a coronal approach must be made for other reasons (such as treating a frontal sinus fracture or harvesting a split calvarium bone graft). Another reason for open treatment is secondary treatment of a zygomatic arch malunion where osteotomy and internal fixation are needed.

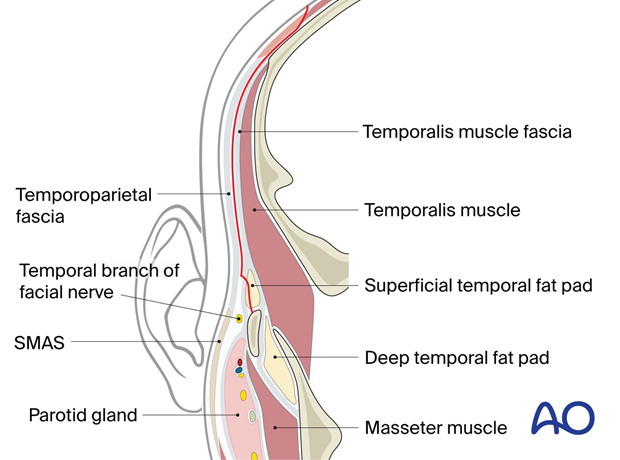

The temporal branch of the facial nerve runs close to the periosteum within the first three centimeters of the posterior portion of the zygomatic arch. Care must be taken to avoid injury to this nerve by staying sub-periosteal in dissection over the anterior surface of the zygomatic arch. The deep temporal fascia splits into anterior and posterior layers to sheath the zygomatic arch. There is a synsarcosis of fat between the layers of the deep temporal fascia over the arch. The dissection should stay within that fat beneath the anterior layer of the deep temporal fascia to protect the facial nerve.

In most patients, there is little soft tissue over the zygomatic arch. If the decision is made to perform an open reduction and internal fixation, the plate size and possible palpability of the plate through the skin should be considered.

2. Computer assisted surgery (CAS) and intraoperative control

CAS and intraoperative CT scan

Computer assisted surgery (CAS) allows intraoperative visualization of the reduction using intraoperative imaging combined with image fusion of preoperative and intraoperative CT scans.

With this technique, insufficient fracture reduction can be identified and corrected intraoperatively, eliminating the need for secondary procedures, which may be necessary if only postoperative imaging is performed. Intraoperative imaging requires an additional 10–15 minutes.

Surgical navigation

Computer assisted navigation can be used to guide the reduction of the zygomatic arch fracture and for assessing reduction and fixation. If available, computer assisted navigation is an effective and minimally invasive technique that can be applied for the confirmation of the reduction and fixation of isolated zygomatic arch fractures.

Virtual planning and patient-specific implants (PSI)

Virtual planning, computer aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM), and 3D printing have further improved the accuracy of restoration of the unique anatomical contour of the zygomatic arch. Based on the CT dataset, a PSI can be manufactured by using CAD-CAM technology. This process significantly reduces the need for intraoperative manipulation of implants and therefore decreases operative time.

To date, there are only a few cases reported in the literature about the use of custom-made PSI for the reconstruction of the zygomatic arch and reconstructive surgery in oncological resections. However, PSI can be used in selected cases where there is extensive comminution and loss of bone segments from the zygomatic arch, which cannot be fixed with a stock plate.

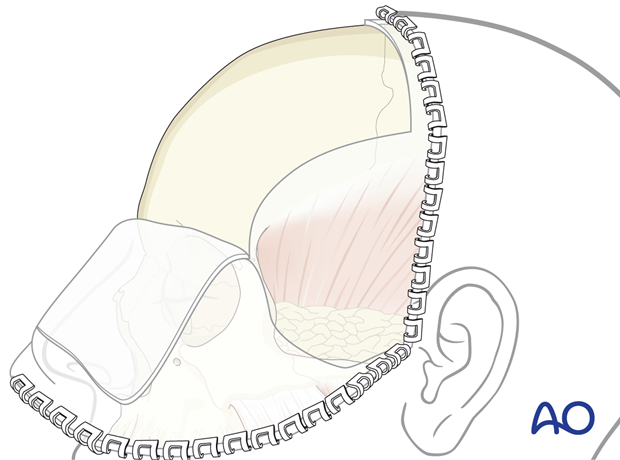

3. Surgical approach

A coronal approach should be performed.

Existing lacerations may also be used.

4. Reduction

The fragments of the zygomatic arch are elevated under direct vision through the coronal approach, using conventional instrumentation.

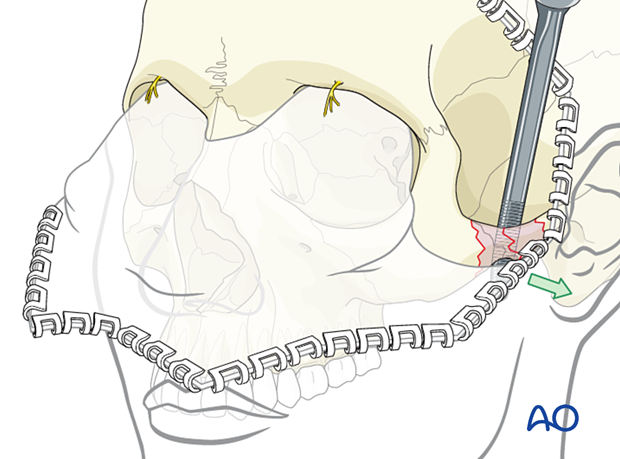

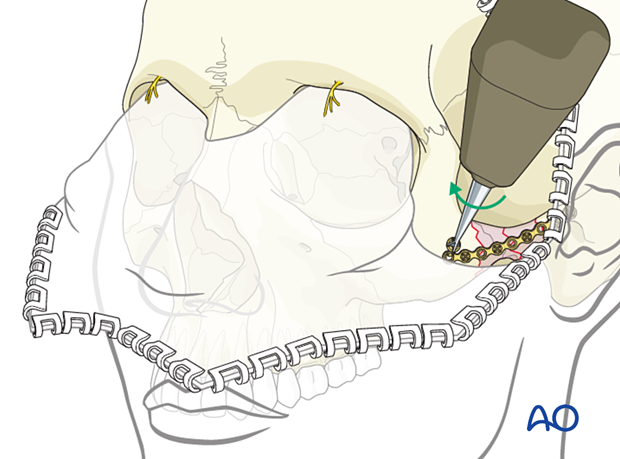

5. Fixation

The order of placement of screws in the fracture segments is highly variable depending on the degree of comminution of the zygomatic arch. One option is to place the first screw next to the fracture on the stable portion of the zygoma and the second screw next to the fracture on the stable portion of the temporal bone, making sure that the entire span of the plate is not canted above or below the zygomatic arch. Additional screws can be placed according to the fracture pattern.

6. Aftercare

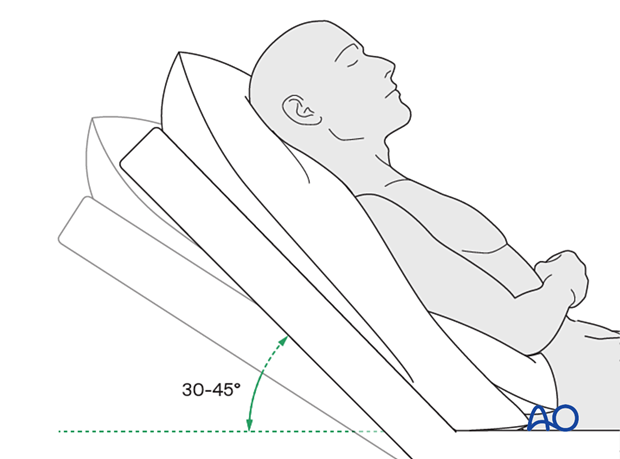

Postoperative positioning

Keeping the patient’s head in a raised position both preoperatively and postoperatively may significantly reduce edema and pain.

Medication

The use of the following perioperative medication is controversial. There is little evidence to make strong recommendations for postoperative care.

- No aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for seven days.

- Analgesia as necessary.

- Antibiotics (Many surgeons use perioperative antibiotics. There is no clear advantage of any antibiotic, and the recommended duration of treatment is debatable.)

- Regular perioral and oral wound care can include disinfectant mouth rinse, lip care, etc.

Postoperative imaging

Postoperative imaging can be considered within the first days after surgery. 2D and 3D imaging (CT, cone beam) are recommended to assess complex fracture reductions. An exception may be made for centers capable of intraoperative imaging.

Wound care

Regular wound care of coronal sutures can include gentle cleaning with a disinfectant swab at least twice a day. Cleansing the hair and scalp can be considered with conditioner and shampoo. Some surgeons prefer the application of antibiotic ointments to sutures.

Remove sutures from the scalp after approximately 8–10 days.

Ice packs may be effective in the short term to minimize edema.

Avoid sun exposure and tanning to skin incisions for several months.

Diet

The patient can resume a normal diet the day following surgery.

A progressive diet should be considered for those with temporalis related injuries.

Clinical follow-up

Clinical follow-up depends on the complexity of the surgery and whether the patient has any postoperative problems.

Issues to consider are:

- Facial deformity (including asymmetry)

- Sensory nerve compromise

- Temporal branch of facial nerve compromise

- Problems of scar formation

Implant removal

Implant removal is rarely required unless requested by the patient or if the implant becomes palpable or visible.

Oral hygiene

Tooth brushing and mouth washes should be prescribed and used at least twice a day to help sanitize the mouth. Gently brushing the teeth occurs with a soft toothbrush (dipped in warm water to make the bristles softer).