Open reduction internal fixation

1. Principles

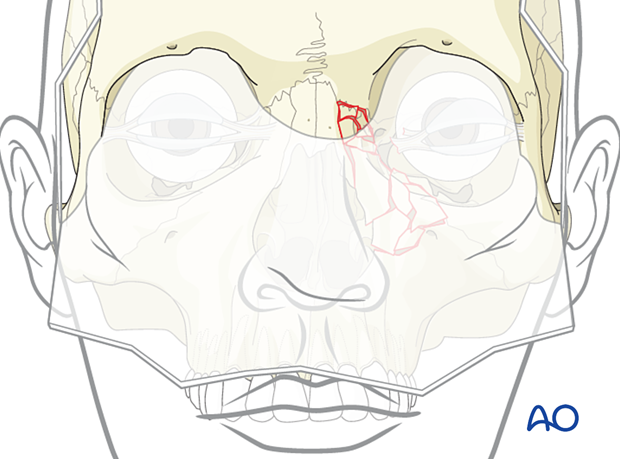

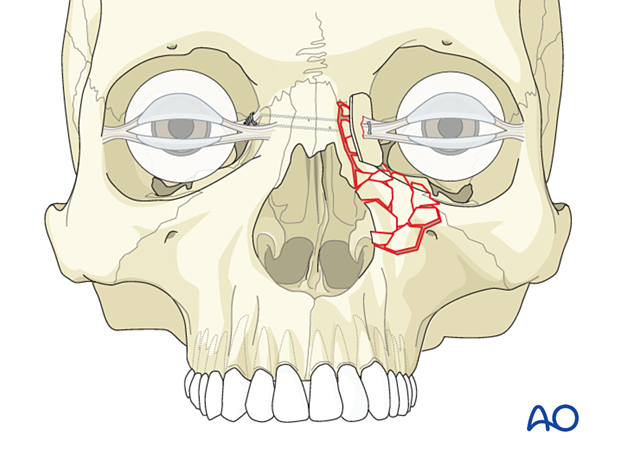

NOE type III represents severely comminuted fractures. The nasal dorsum is almost always extensively comminuted, as is the frontal process of the maxilla. The medial canthal tendon is avulsed from its bony insertion, requiring canthopexy. These fractures usually require 3-point exposure and fixation.

The intercanthal distance should be restored.

Rule out CSF leaks, particularly in bilaterally displaced fractures, to minimize the risk of early or delayed meningitis. Always make sure to rule out injuries to the globes and the lacrimal apparatus.

The support and projection of the nose should be restored.

Great care should be taken when considering placing plates anterior to the medial canthal ligament, as these may be visible through the thin overlying skin.

Nasal bone involvement

If nasal bones are also fractured, they should be addressed and reduced. Interfragmentary wires (# 28) unite the nasal bone fragments one to another. Microfixation plates may supplement the interfragmentary wire technique.

If the dorsum of the nose is comminuted, it is challenging to fully reconstruct nasal height. A thin or thicker dorsal nasal bone graft used immediately can smooth irregular contour or supplement deficient nasal height.

Bilateral NOE fracture with nasal bone involvement

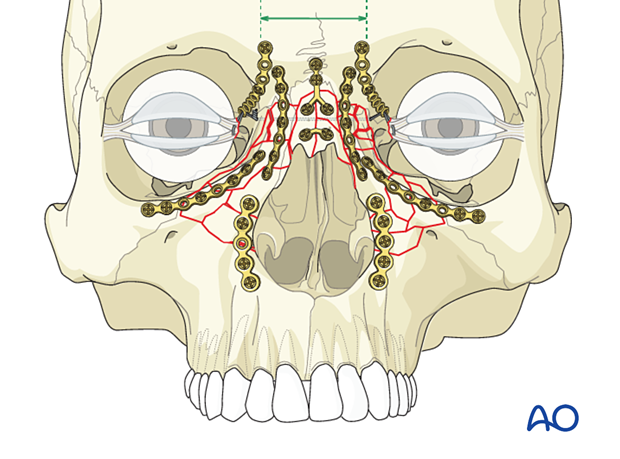

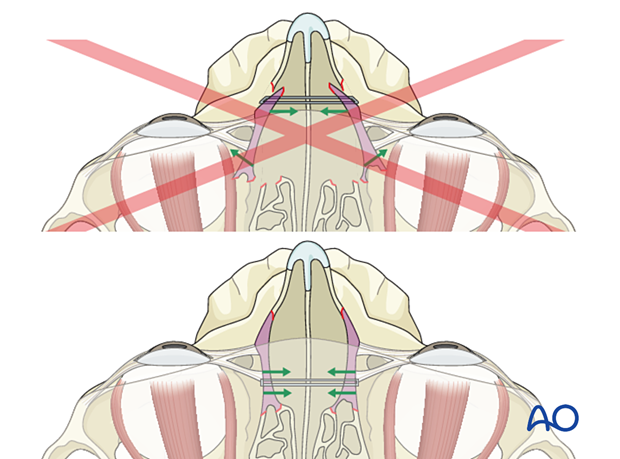

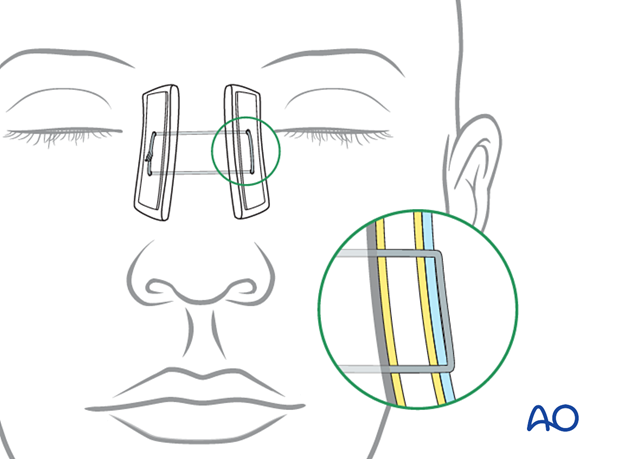

NOE type II and III fractures commonly occur bilaterally. Two #28 full-length transnasal wires are placed capturing the canthal ligaments and then tightened to restore the intercanthal distance by drawing the canthi towards each other.

A slight overcorrection of the intercanthal distance should be considered. The recommended soft tissue intercanthal width is 33–34 mm for white males and 32–33 mm for white females. The bone intercanthal distance is less than the soft tissue distance by 5 mm per side, which equates to 22–24 mm. Little data is available for other ethnic groups.

Transnasal wires passed through plates may be harder to hold in position and have a more challenging problem in correcting the intercanthal distance.

2. Selection of approach

The most common access for reduction of NOE fractures includes a combination of surgical approaches such as coronal, lower eyelid transcutaneous or transconjunctival, and maxillary vestibular incisions. For localized (central alone) NOE fractures, direct access can be achieved by an incision along the horizontal limb of the converse open sky incision (NO vertical component). This incision can provide direct access to the fracture and is often used in elderly patients. Sometimes there is an existing laceration that can also provide direct access.

The coronal approach is preferred when multiple fractures of the upper face or the frontal bone exist concomitantly. It also provides access for harvesting calvarial bone graft that can be used to restore the projection of the nose in severely comminuted fractures.

3. Reduction

NOE type III fractures are some of the most complex facial fractures to properly reduce. The reasons for the difficulty include small fracture fragments, challenging access via multiple surgical approaches, and medial canthal ligament control problems.

Fractures which require reduction via several approaches are uniquely challenging because the surgeon has to continuously control the reductions at the different sites by switching between approaches. Some surgeons use temporary interosseous wires, or intentionally do not tighten screws in plates, to allow for finetuning the reductions at different sites before final tightening the screws.

4. Fixation

General considerations

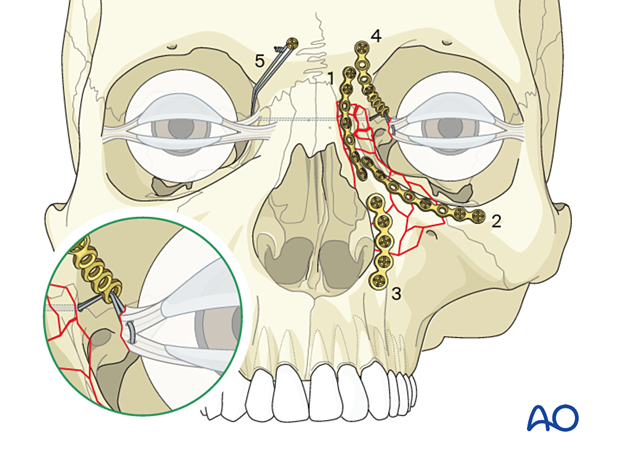

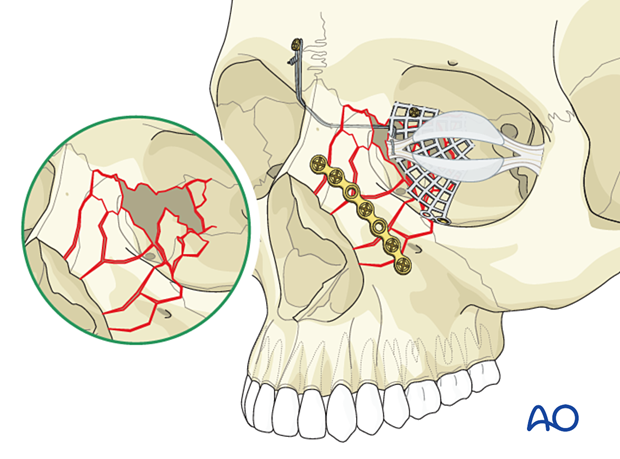

NOE type III fractures represent comminuted fractures where the medial canthus has become detached from the bone. A transnasal canthopexy must reattach the canthus in its proper position. The medial canthal ligament should be repositioned just above and behind the superior aspect of the lacrimal fossa. The medial canthus is attached with a separate set of transnasal wires brought through the described drill hole on the ipsilateral side, passed across the nose to the contralateral side, and draped over a screw placed in the glabellar area of the contralateral frontal bone. The wire is then tightened. The most important aspect is the medial and posterior positioning of the medial canthal ligament.

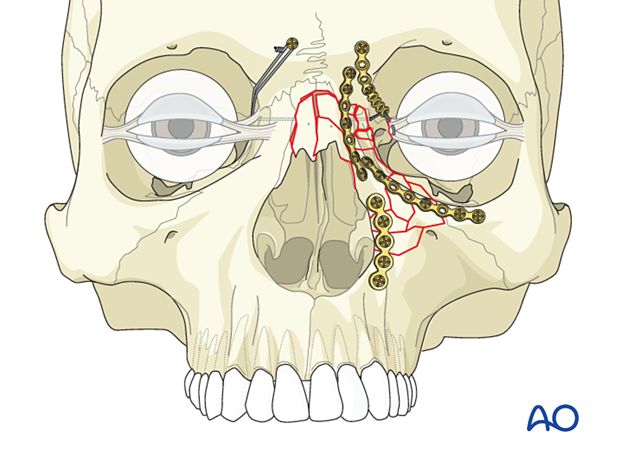

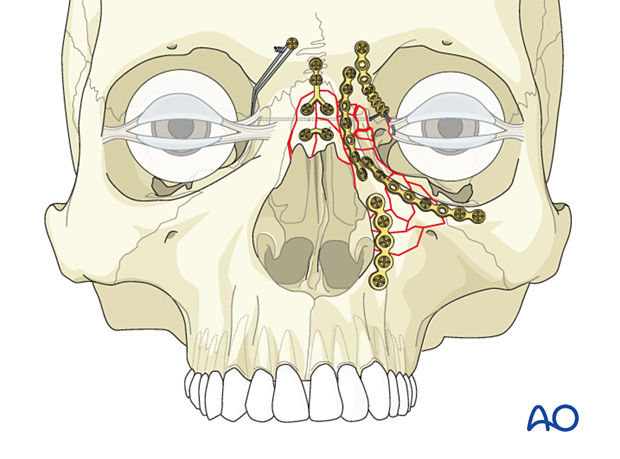

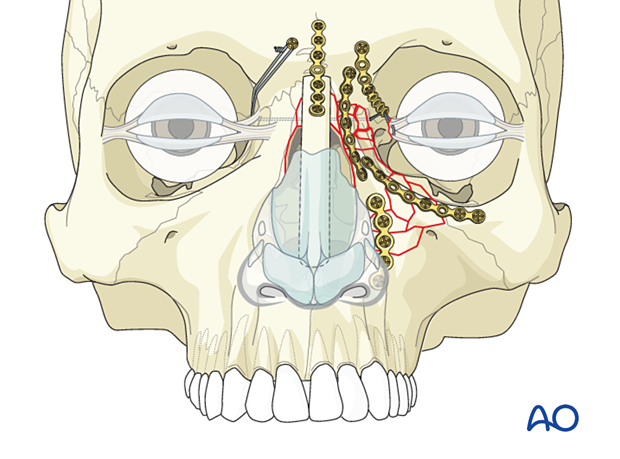

Commonly, a minimum of three points of fixation will be needed. This will include plating at the NOE/frontal bone (1), a plate along the orbital rim (2), and a plate along the piriform aperture (3). Additional plates may be needed to stabilize the comminuted fracture segments.

The first plate is placed where the surgeon has the best visualization and access, with the most well-defined landmarks. If a surgeon has good visualization at all three points, it may be beneficial to fixate from the more stable fractures to the least stable fractures. A consideration is to first stabilize the NOE fracture to the frontal bone, achieving stabilization to the calvarium, with the second plate placed along the orbital rim, and the third plate placed along the piriform aperture. This prioritizes plate placement according to the order of esthetic importance and buttress stability.

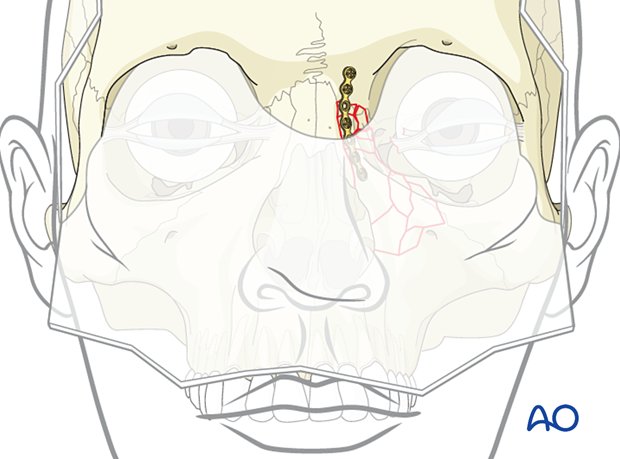

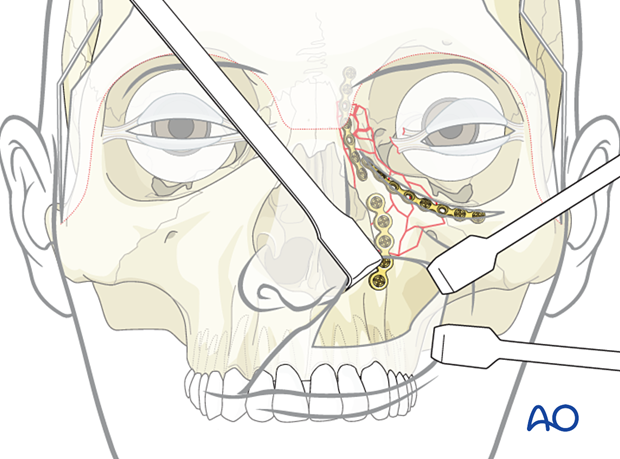

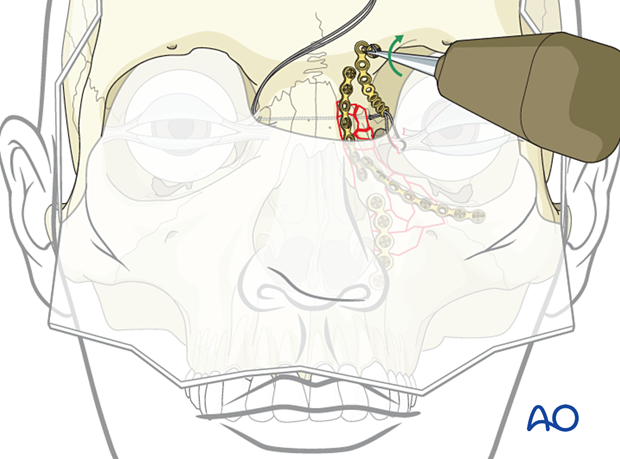

Placement of first plate

In the accompanying illustration, the first plate is applied to the fracture between the NOE and the frontal bone through the coronal approach. (This can also be achieved through an extended glabellar approach.)

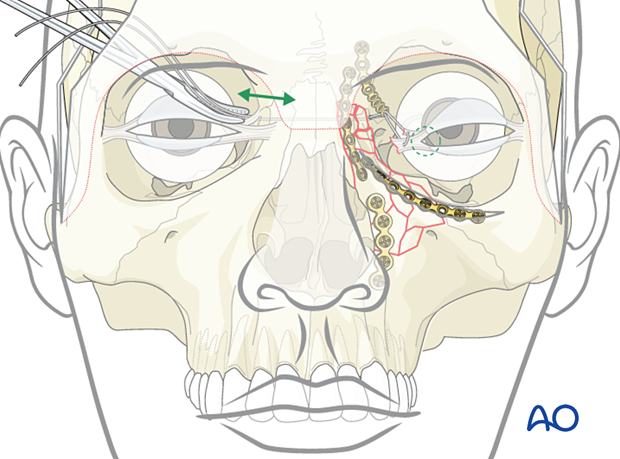

Placement of second plate

The second plate is then placed along the orbital rim through the inferior lid approach.

Placement of third plate

A third plate is placed along the piriform aperture through the maxillary vestibular approach.

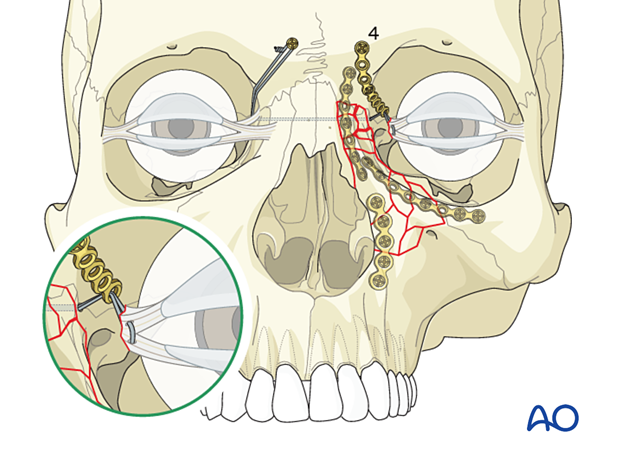

5. Placement of transnasal canthopexy wire

Introduction

A transnasal canthopexy wire is preferred to secure the medial canthal tendon above and behind the lacrimal fossa. One technique is the use of a plate hole to guide the position of the transnasal wire for the medial canthus.

In such a case, a fourth plate is utilized to hold the medial canthus in its proper posterior and horizontal 3-dimensional position. This can be achieved using the anchor technique (as illustrated).

A wire can be used to engage and fix the medial canthal ligament, passed through the plate hole, across the nose, and threaded over the contralateral frontal bone fixation screw.

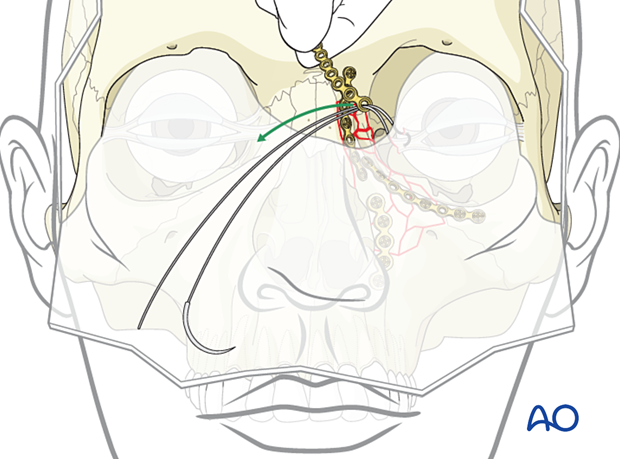

Identifying the medial canthus

The first step in the canthopexy is to locate the medial canthus.

The medial canthus can be identified by using forceps through the coronal or extended glabellar approach. The forceps are used to find and pull on the medial canthus while observing the skin in the medial canthal area to confirm that the proper structure has been identified.

If the surgeon is having difficulty identifying the medial canthal ligament, a small vertical skin incision directly over the canthal ligament just medial to the canthal angle exposes the ligament for direct visual fixation.

Once the medial canthus has been identified, the transnasal wire is placed through the medial canthus. A metal wire with a detachable swaged-on needle should be used.

Usually, it is sufficient to pass the wire only once through the tendon.

Adapt fourth bone plate and pass wire through it

If the fracture pattern does not allow the transnasal wire to be placed in its proper 3-dimensional location, a plate hole may be used to help position the transnasal wire.

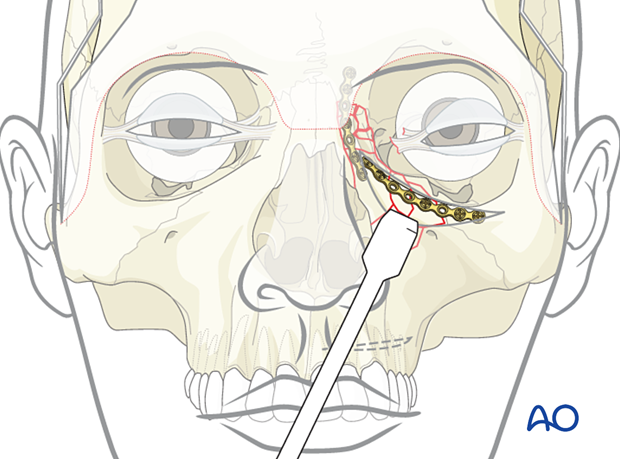

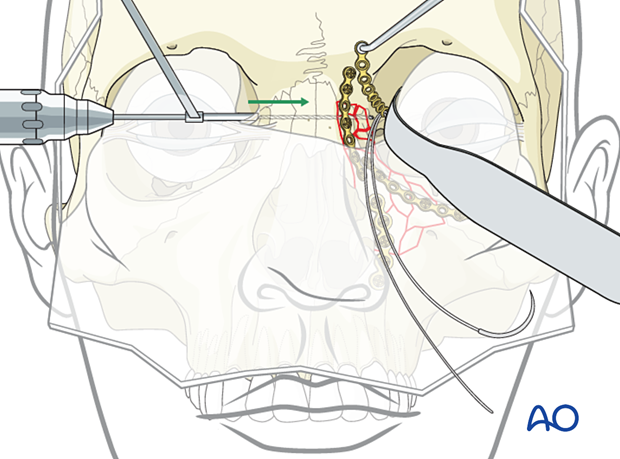

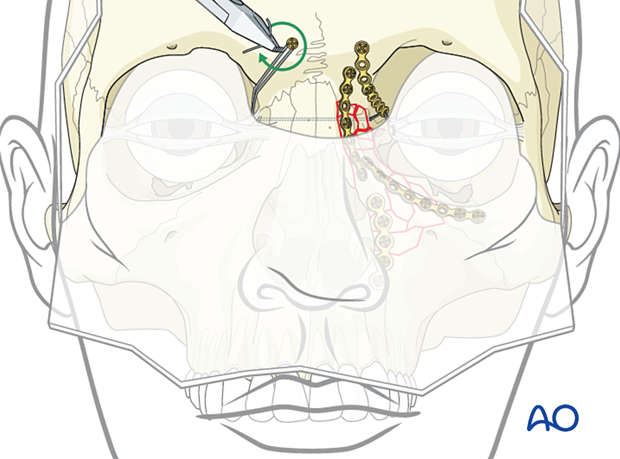

Create hole for the wire

Depending on the stability of the bone in the NOE area, the surgeon may need to drill a hole from the contralateral side or use an awl to create a passageway. Many different techniques have been used to accomplish this. These include the use of a drill or a spinal needle. Extreme caution must be used to ensure that the spinal needle or drill bit does not injure the contralateral globe.

When passing transnasal wires, the contralateral eye must be protected. It is important to use a malleable retractor or spoon retractor to protect the globe. The retractor should be placed deep enough in the contralateral orbit to protect the globe.

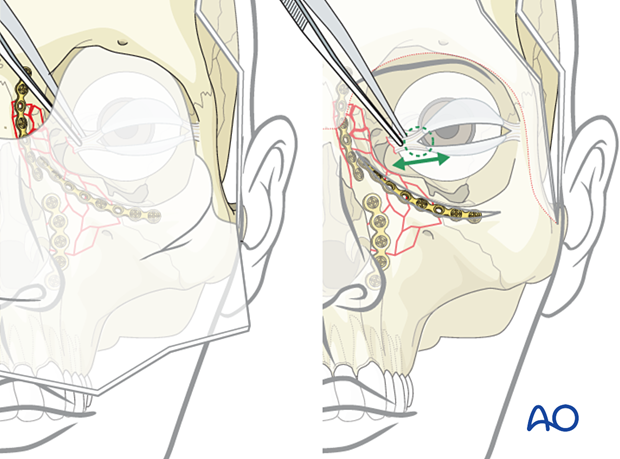

Pull the wire through the hole

While the spinal needle is still in place, the two ends of the wire are placed through the lumen of the needle, and both the spinal needle and wire are pulled out of the contralateral side of the NOE fracture.

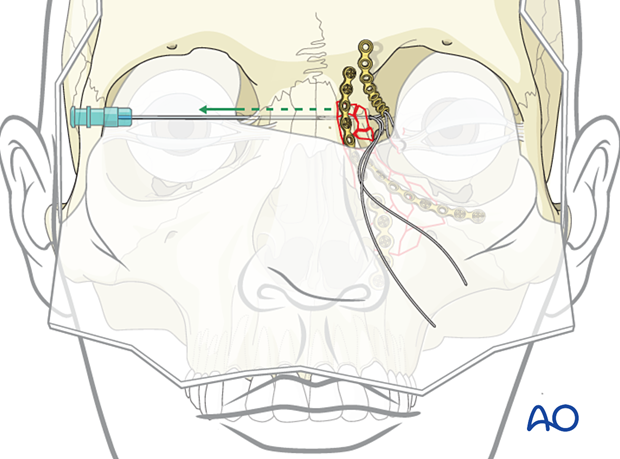

Alternative: using an awl

In this illustration, an awl has been placed through the contralateral side and then advanced to the side of the fracture. The wire has been placed through the fragment attached to the medial canthus.

The two ends of the wire are then passed to the contralateral side using the awl.

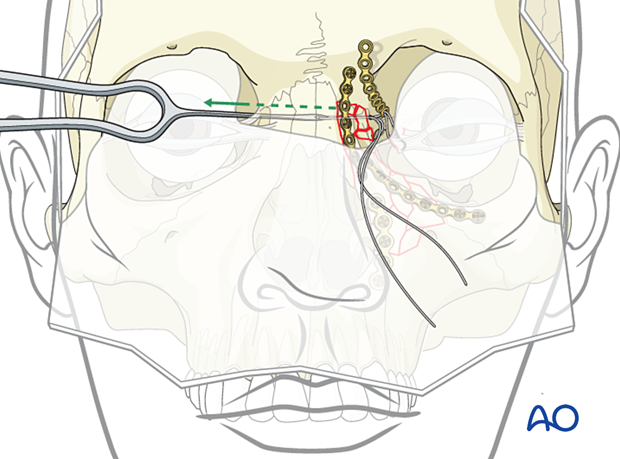

Fixation of fourth plate

The fourth plate is placed to secure the transnasal wire in its proper location. The plate is secured superiorly to the frontal bone.

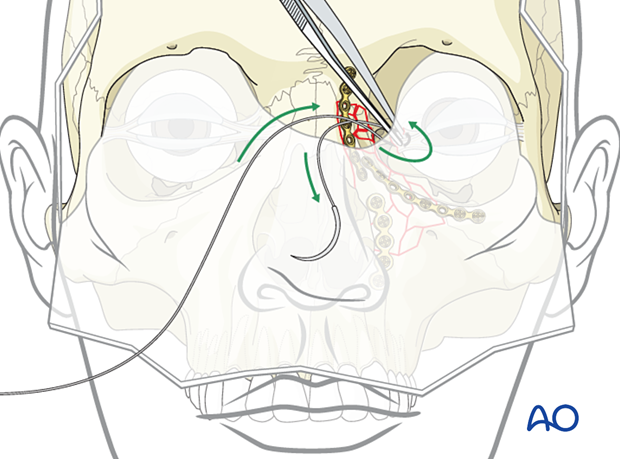

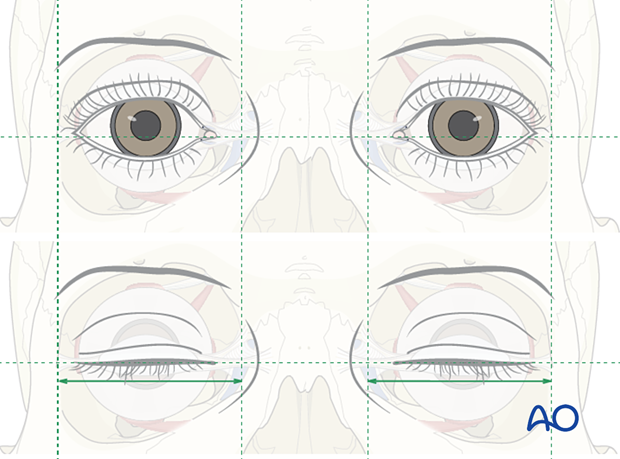

Rechecking medial canthal area

It is recommended that the surgeon perform a final check to confirm the correct position of the medial canthus.

Video demonstrating how to check the correct position of the medial canthus.

Securing transnasal wire

The transnasal wire is secured to a screw placed in the contralateral frontal bone and tightened with the appropriate tension needed to secure the medial canthus into its proper position (intercanthal distance).

While some surgeons have used plates alone to replace a canthal bearing bone structure, experience has shown that this is often not a stable technique because of the absence of normal bone fixation and deterioration of canthal position with time.

Alternative support for the transnasal canthopexy wire

Most commonly, there is sufficient bone in the area where transnasal wiring of the canthal ligament needs to be accomplished to pass the wires through a drill hole in the canthal bearing bone fragment. This technique is preferred. If sufficient bone is not available, the preferred technique involves placing an appropriate bone graft to reconstruct the bone normally bearing canthal ligament insertion.

Proper position of transnasal wire

AP position of the transnasal wireNOE fractures often result in a lateral splaying of the medial canthi, resulting in telecanthus. The placement of a transnasal wire can usually correct this.

When confronted with an NOE fracture requiring a transnasal wire, it is important to place the wire fixation in its proper posterior position. The upper illustration represents a wire that has been placed too anteriorly, resulting in a further lateral splaying of the bone supporting the medial canthus and a worsening of the telecanthus.

The lower illustration represents the proper posterior placement of the transnasal wire with an adequate reduction of the bone attached to the medial canthus.

While the AP projection of the medial canthi is important, the horizontal position of the canthi is also critical.

With the eyelids closed and in a relaxed position, the lateral canthi should fall into a horizontal position with the medial canthi.

6. Soft tissues

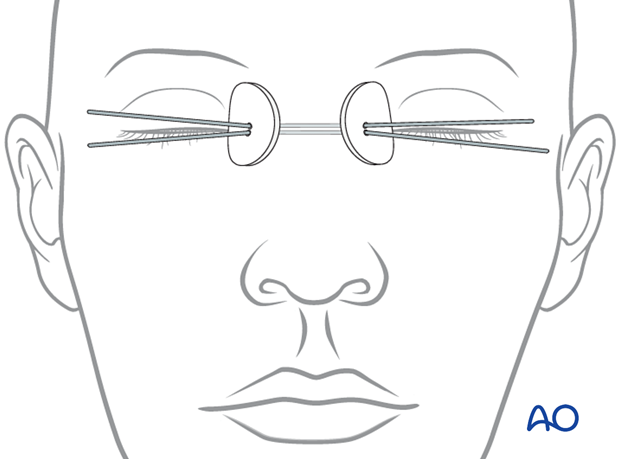

A problem with NOE fractures is that even with a perfect bony reduction, there may be a lack of definition of the soft tissue in the medial canthal area. Many surgeons advocate placing external nasal splints at the end of the procedure to ensure close adaptation of the soft tissue to the underlying bone.

A soft tissue "bolster" pad is applied to the sides of the nose to recreate the correct angle of the soft tissue between the base of the nose and the medial cheek. Soft tissue bolsters are fixed with a wire passing through the bone to the contralateral side and tightened into place.

This technique becomes more relevant with increasing complexity of the NOE fracture. It is not usually necessary in type I NOE fractures. The more soft-tissue degloving of the nasal and medial maxilla, the more this technique is relevant to recreate the normal soft tissue draping in this region. It is most relevant for achieving the reduction and fixation of the fractured segments in type II and type III fractures where the soft tissue is totally stripped from the bone.

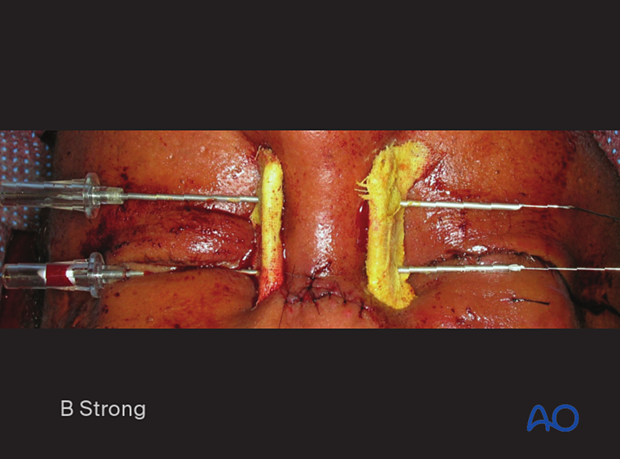

The percutaneous bolster dressing can be fixed in place with the use of transnasal wires or sutures.

The #28 full-length wires are passed through a 16-gauge spinal needle across the nasal bones. They are tightened into place to stabilize the bolster and maintain the coaptation of the soft tissue snugly onto the bone.

Due to the comminuted fractures the wires can be passed through drill holes or gaps between fracture segments.

Clinical photograph showing a percutaneous bolster dressing.

The bolsters consist of a half-thickness of orthopedic felt wrapped with Xeroform and stabilized by 2.0 mm thick Supramid plastic sheeting.

7. Aftercare

Evaluation of the patient’s vision

Patient vision is evaluated on awakening from anesthesia and then at regular intervals until hospital discharge.

A swinging flashlight test may serve to confirm pupillary response to light in the unconscious or non-cooperative patient; alternatively, an electrophysiological examination must be performed but this is dependent on the appropriate equipment (VEP).

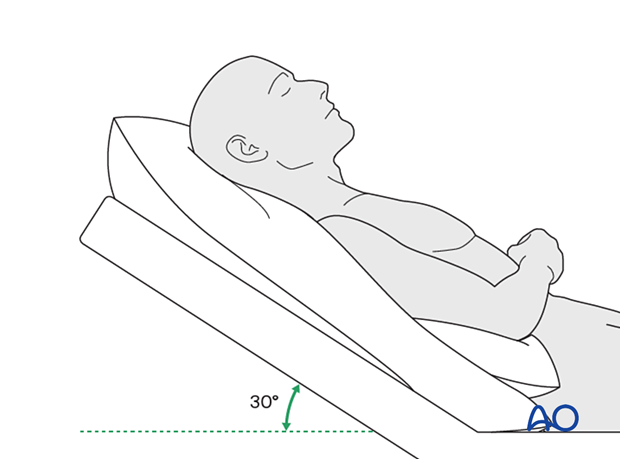

Postoperative positioning

Keeping the patient’s head in a raised position both preoperatively and postoperatively may significantly reduce edema and pain.

Nose blowing

Nose blowing should be avoided for at least 10 days following NOE fracture repair to prevent orbital emphysema.

Medication

The use of the following perioperative medication is controversial. There is little evidence to make solid recommendations for postoperative care.

- No aspirin for seven days (use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)is controversial)

- Analgesia as necessary

- Antibiotics (Many surgeons use perioperative antibiotics.) There is no clear advantage of any antibiotic, and the recommended duration of treatment is debatable.

- A nasal decongestant may be helpful for symptomatic improvement in some patients.

- Steroids, in cases of severe orbital trauma, may help with postoperative edema. Some surgeons have noted increased complications with perioperative steroids.

- Ophthalmic ointment should follow local and approved protocol. This is not generally required in the case of periorbital edema. Some surgeons prefer it. Some ointments have been found to cause significant conjunctival irritation.

Ophthalmological examination

Postoperative examination by an ophthalmologist may be requested. The following signs and symptoms are usually evaluated:

- Vision

- Extraocular motion (motility)

- Diplopia

- Globe position

- Visual field test

- Lid position

- If the patient complains of epiphora (tear overflow), the lacrimal duct must be checked

- If the patient complains of eye pain, evaluate for corneal abrasion

Postoperative imaging

Postoperative imaging must be performed during the first days after surgery. 3D imaging (CT, cone beam) is recommended to assess complex fracture reductions. An exception may be made for centers capable of intraoperative imaging.

Wound care

Remove sutures from the skin after approximately five days if non-resorbable sutures have been used.

Medial canthal bolster dressings should be kept in place for a minimum of 2–4 weeks to allow proper skin redraping. If bolsters are utilized, one must clean under the bolster daily with peroxide on cotton-tip applicators and a small amount of antibiotic ointment may be applied underneath. The tension on the bolster is frequently adjusted in the early postoperative period to avoid excess pressure on the skin creating ischemia. Ice compresses may be applied to the eyelids to provide comfort, slight anesthesia, and to minimize swelling.

Avoid sun exposure and tanning to skin incisions or periorbital bruising for several months to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Diet

Diet depends on the fracture pattern and the patient’s condition, but there are usually no limitations.

Clinical follow-up

Clinical follow-up depends on the complexity of the surgery and whether the patient has any postoperative problems.In all patients with NOE trauma, all the following should be periodically assessed:

- Globe position

- Double vision

- Other vision problems

- Nasal airway status

Other issues to consider are:

- Facial deformity (including asymmetry and pseudo-telecanthus)

- Sensory nerve compromise

- Problems of scar formation

- Anosmia

- Epiphora and dacryocystitis

Implant removal

Generally, implant removal is not necessary except in the event of infection or exposure.

Special considerations

Travel in pressurized aircraft is permitted 4–6 weeks postoperatively. Mild pain on descent may be noticed. However, flying in a non-pressurized plane should be avoided for a minimum of 6 weeks.

No scuba diving should be permitted for at least 12 weeks. Additionally, the patient should be warned of potential long-term risks.