Open medial epicondylar reduction and internal fixation

1. Principles

Instrumentation

When the medial epicondylar fragment is of sufficient size, a 3.5 mm or 4.0 mm cancellous cannulated screw is the preferred fixation.

A washer can also be used, but this increases the likelihood of subsequent need for implant removal.

If the fragment is small or fragile, one or two K-wires can be used.

2. Patient preparation

The procedure is performed with one of the following patient positions:

3. Approach

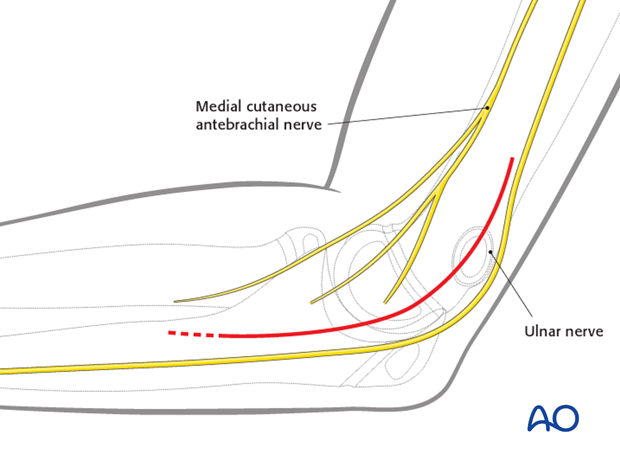

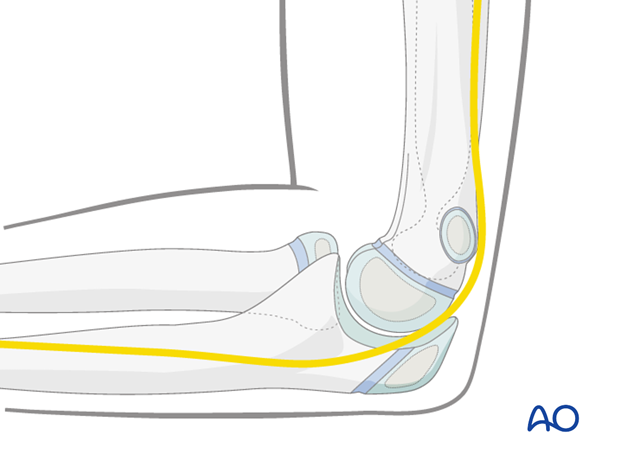

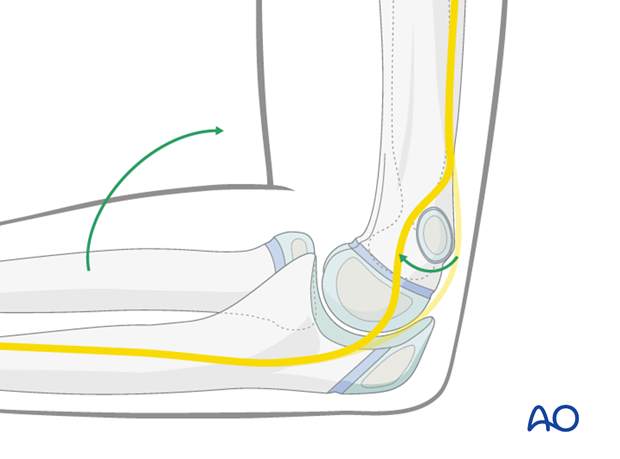

For this procedure a medial approach is normally used.

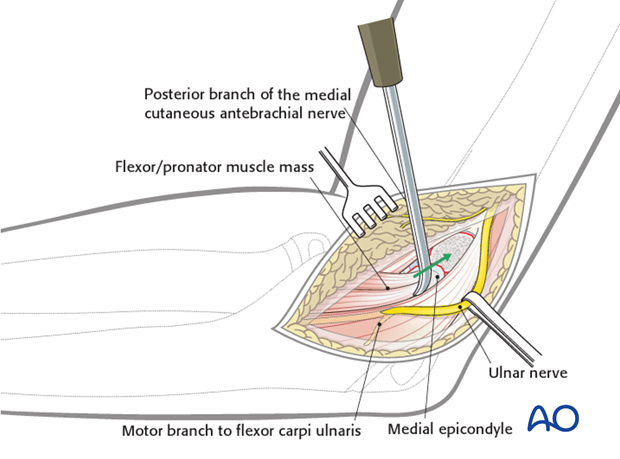

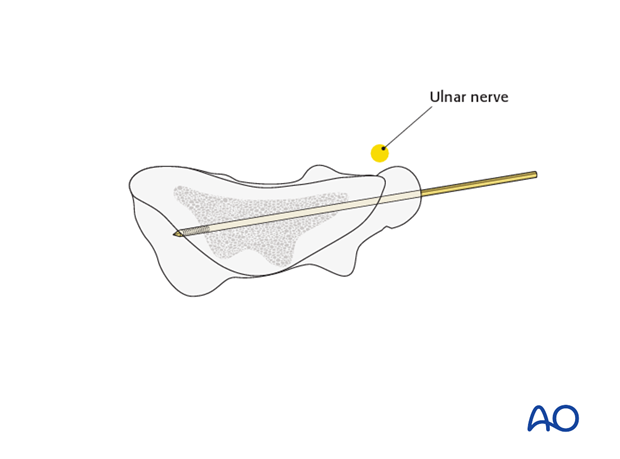

The ulnar nerve is potentially vulnerable during the approach.

Soft tissue swelling associated with the fracture and with elbow dislocation may obscure the position of the anatomical landmarks.

In addition, the nerve may be immediately subcutaneous or lie within the joint.

Identification and protection of the nerve is presumed.

Note: In many children the ulnar nerve can sublux forwards onto, or anterior to, the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.

This may be easier to demonstrate on the contralateral, uninjured elbow and is difficult to appreciate in a swollen and injured limb.

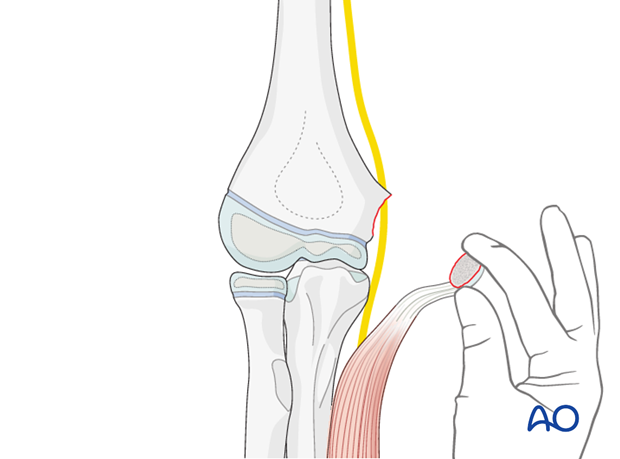

4. Open reduction

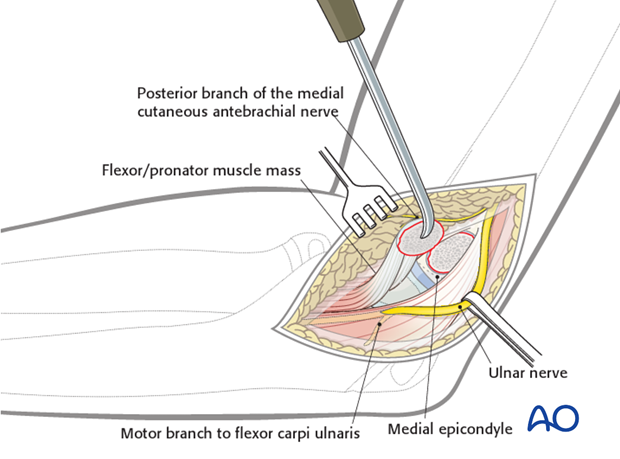

The medial epicondyle is identified.

The flexor-pronator origin usually forms a large soft tissue mass, which is attached to this small fragment of bone.

As much of the flexor-pronator origin as possible should be preserved.

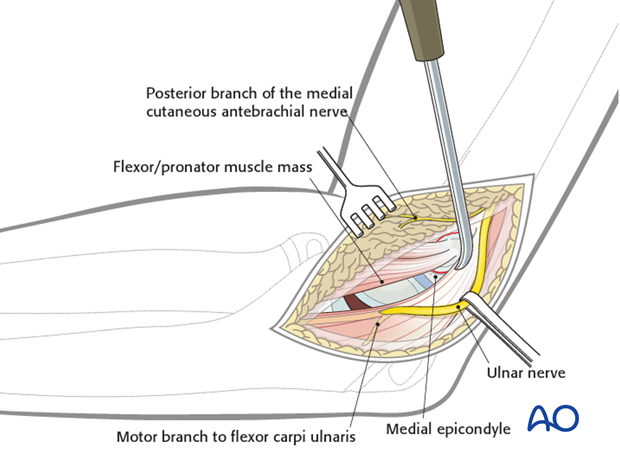

The medial epicondyle and flexor/pronator origin are reflected medially and distally to identify the metaphyseal surface of the avulsed apophysis.

This surface may be a bony or cartilaginous bed, depending on the maturity of the child. Minimal dissection is necessary to preserve capsular attachments.

Both surfaces of the fracture should be cleaned and irrigated.

The appropriate orientation and position of the medial epicondylar fragment is determined.

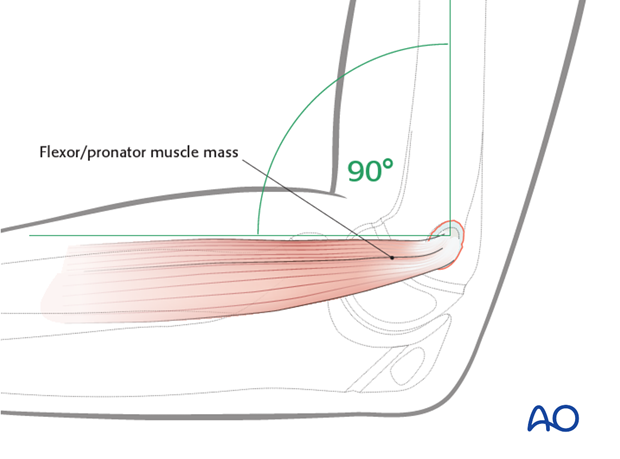

A key to reduction is that the fibers of the flexor/pronator origin should be at 90° to the humeral shaft with the elbow at a right angle.

The medial epicondyle is reduced onto its bed.

The soft tissues often obscure a view of the fracture edges at this stage.

5. Fixation

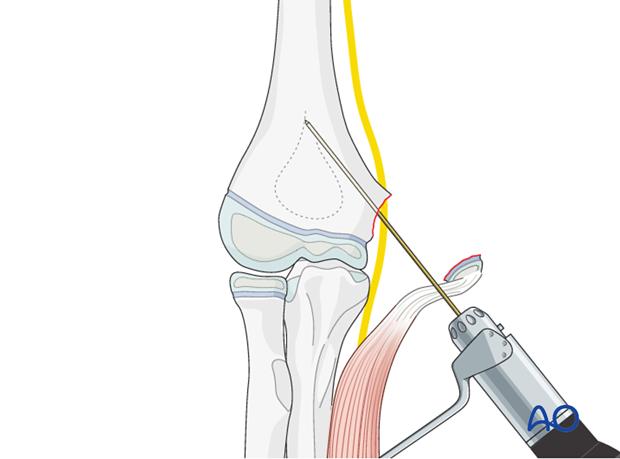

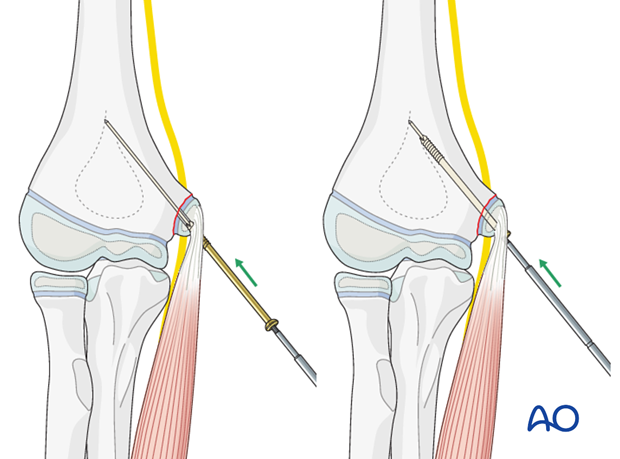

Screw fixation

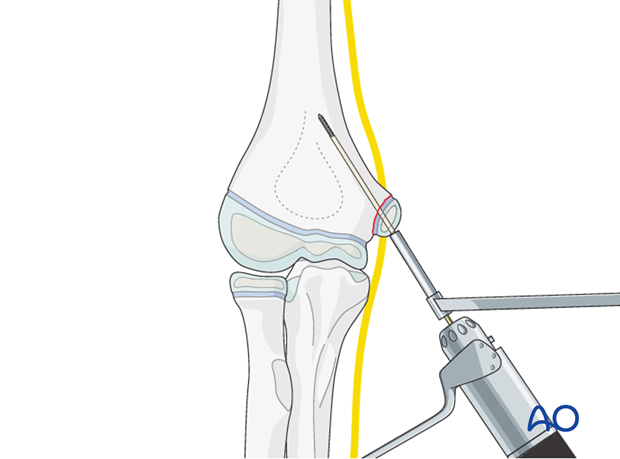

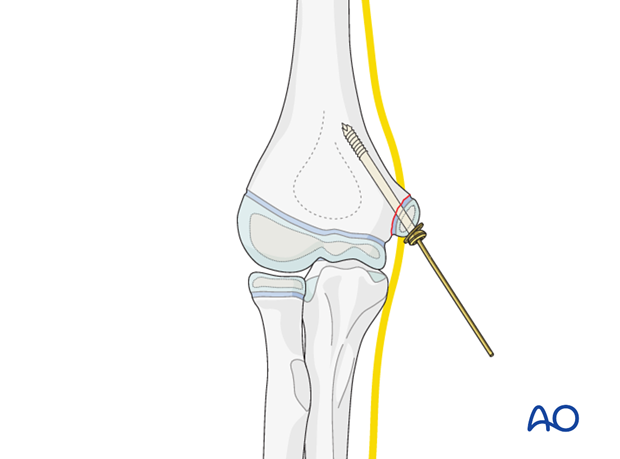

A guide wire is inserted centrally into the medial epicondyle.

A drill guide is used to protect soft tissues.

The guide wire is advanced into the medial column.

The position of the guide wire and reduction of the epicondyle are confirmed on AP and lateral image intensifier views.

It may be necessary to adjust the reduction or wire fixation in order to obtain an anatomical position of the medial epicondyle.

Once acceptable reduction is obtained, a single cancellous cannulated lag screw is inserted over the guide wire, using a washer if required.

Once the screw is fully inserted, the guide wire is removed.

Alternative: K-wire fixation

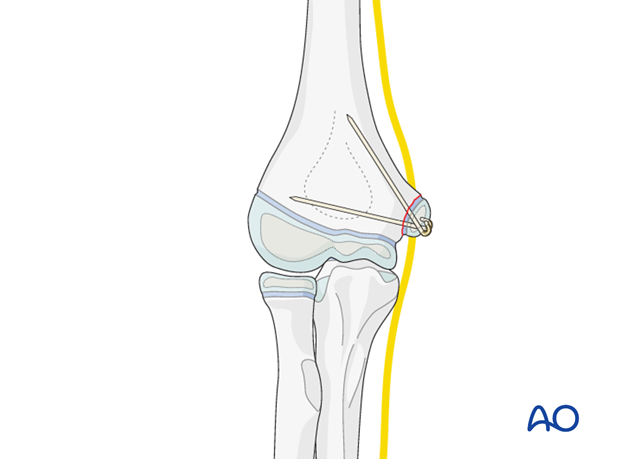

If the fragment is small, one or usually two K-wires can be used as definitive fixation.

The ends of the K-wires are cut obliquely, bent through 180° and impacted into the epicondyle.

6. Alternative: Inside–out technique for indirect reduction and fixation

General considerations

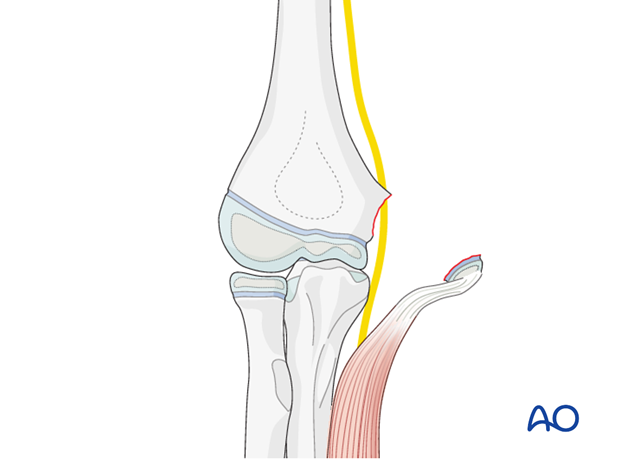

As the fragment is covered by the muscle/ligament attachment, after digital reduction it may be difficult to localize the center and the deepest part of the fragment. Therefore there is a risk of inadequate fixation or even splitting of the fragment.

A safe and straight forward inside-out technique is useful, guaranteeing that the fragment is always fixed via its strongest part.

The reduction is then performed indirectly and fixed with a lag screw (preferable cannulated).

Note: Even though the reduction may not be anatomical, with a small step in the fracture surface, the main goal of stable and safe fixation has been achieved. This allows early functional postoperative management.

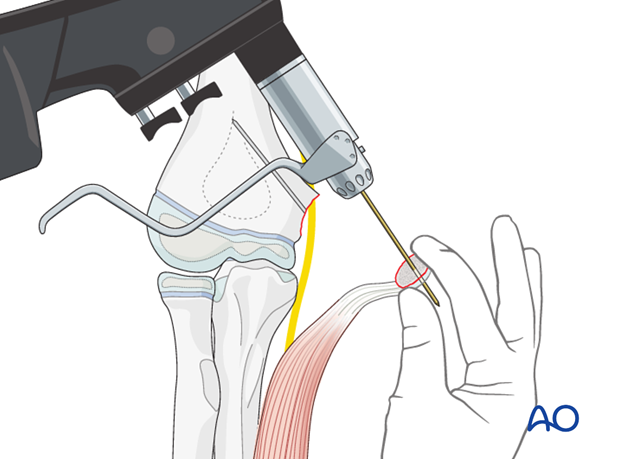

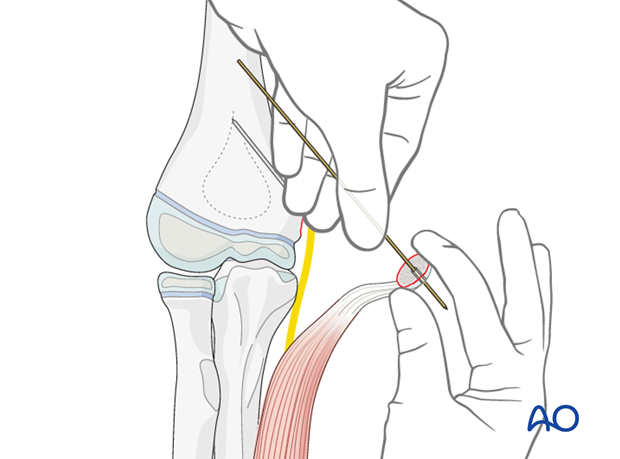

Technique

Both the fracture surfaces are debrided and the fracture hematoma is washed out.

It is not absolutely necessary to expose the ulnar nerve unless it is trapped within the fracture.

A hole is made in the center of the metaphyseal surface using a 1.6 or 2.0 mm K-wire (or a 2.0 or 2.5 mm drill) within the ulnar column, as illustrated.

The epicondylar fragment is held digitally and a hole is similarly created through the center of the fracture surface from inside out, as illustrated.

As the bone of this fragment can be hard and sometimes also very small, it is safer to make the hole a little larger, using a 2.5 mm drill. This prevents splitting of the fragment when the lag screw is inserted.

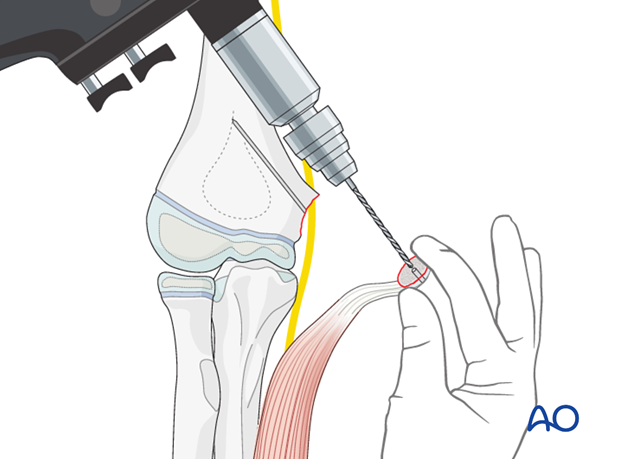

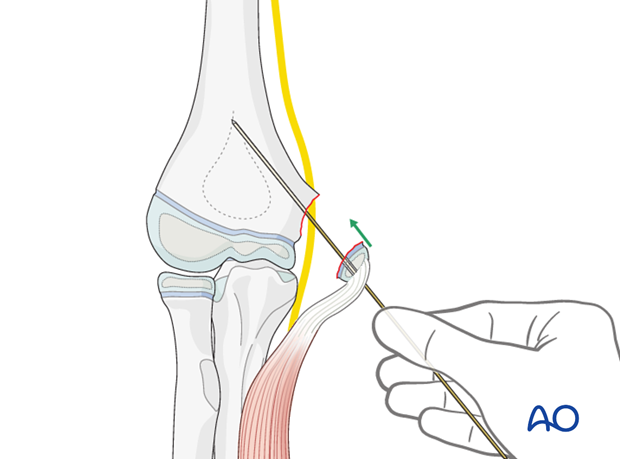

A guide wire for a cannulated lag screw is then inserted by hand from inside-out leading with the pointed tip.

The blunt end of the K-wire is then introduced into the metaphyseal hole and the fragment is pushed along the guidewire into a reduced position.

An appropriate screw, depending on the fragment size, is then passed over the guide wire and driven home.

As the screw is finally tightened, the fragment is held to prevent its rotating.

7. Immobilization

Early motion is preferred. After elbow dislocation, a removable posterior splint is worn. The parents/carers can then take this off from time to time for gentle active elbow motion, once the child is comfortable.

For the first few days, the elbow and forearm can be elevated on a pillow, until swelling decreases and comfort returns.

At this point, the child may choose to use a sling to support the arm. Many children are more comfortable without a sling.

8. Aftercare

Analgesia, including ibuprofen and paracetamol, should be administered regularly.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a possible early postoperative complication that may be difficult to diagnose in younger children.

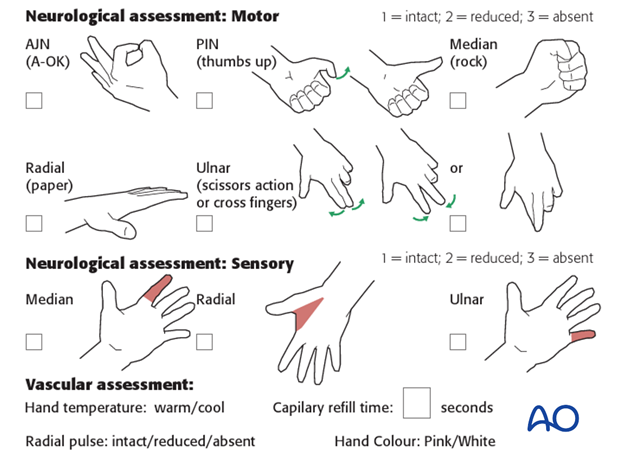

The child should be examined frequently, to ensure finger range of motion is comfortable and adequate.

Neurological and vascular examination should also be performed.

Increasing pain, decreasing range of finger motion, or deteriorating neurovascular signs should prompt consideration of compartment syndrome.

See also the additional material on postoperative infections.

Discharge care

When the child is discharged from the hospital, the parent/caregiver should be taught how to assess the limb.

They should also be advised to return if there is increased pain or decreased range of finger motion.

It is important to provide parents with the following additional information:

- The warning signs of compartment syndrome, circulatory problems and neurological deterioration

- Hospital telephone number

- Information brochure

Follow-up x-rays

Control x-rays may be taken at one week following injury to assess fracture position. Further x-rays may be necessary at three weeks to assess fracture healing. This should be performed after the splint has been removed.

Removal of splint

Splints are usually removed within 2 weeks of the injury.

Recovery of motion

As symptoms recover, the child should be encouraged to remove the sling and begin active movements of the elbow.

The majority of elbow motion is recovered rapidly, usually within two months of splint removal. The older child may take a little longer.

Once the child is comfortable, with a nearly complete range of motion, he/she may resume noncontact sports incrementally. Resumption of unrestricted physical activity is a matter of judgment for the treating surgeon.

implant removal

Implants are removed according to local practice.