Closed reduction; K-wire fixation

1. Principles/Introduction

General considerations

For fractures in which the distal fragment is posterior to the shaft (about 95% of fractures), closed reduction often, but not always, results in an anatomical reposition and good preliminary stability, due to an intact posterior periosteum.

Without such good stability, or with the distal fragment anterior to the shaft (a flexion type supracondylar fracture), the reduction and pinning technique need to be modified.

See also the additional material on closed reduction of supracondylar fractures.

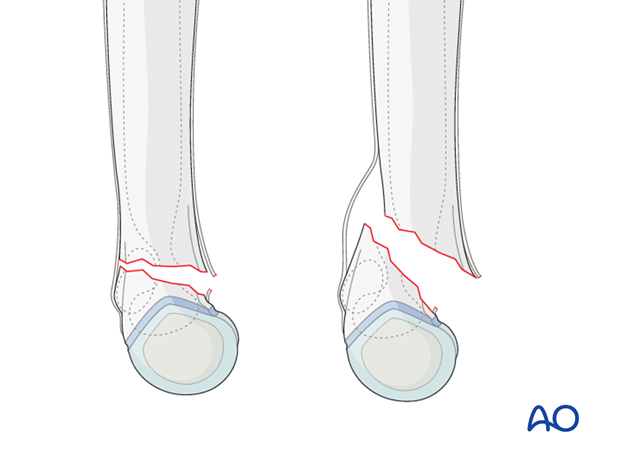

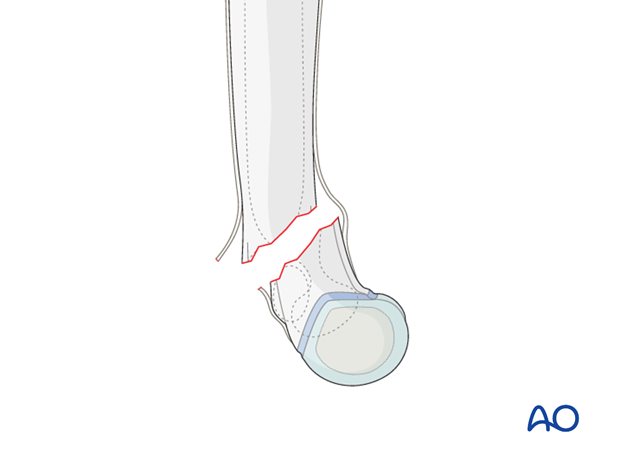

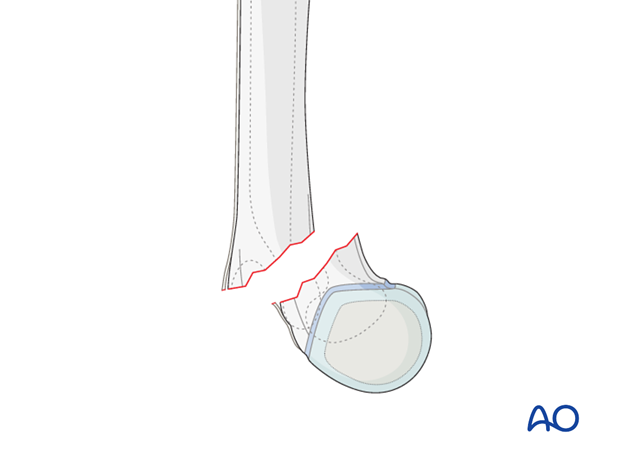

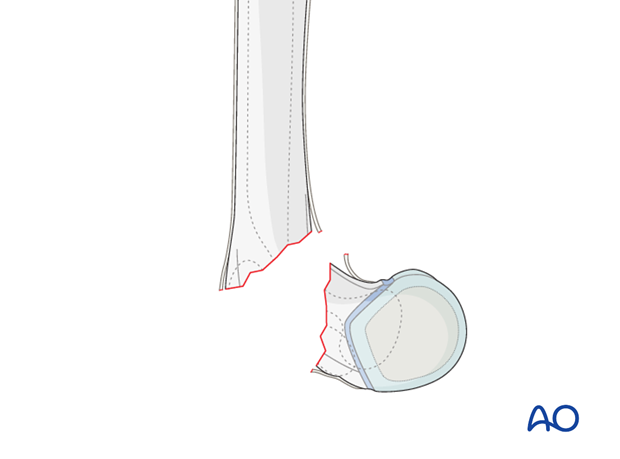

How periosteum can aid stability after reduction

The intact posterior periosteum can confer stability once the fracture is reduced and the elbow is held in maximal possible flexion.

As the periosteum has a fixed length, a closed reduction will be easier if the fracture line is transverse, or high posteriorly, on the lateral view.

A closed reduction may be challenging if the fracture line is low posteriorly on the lateral view.

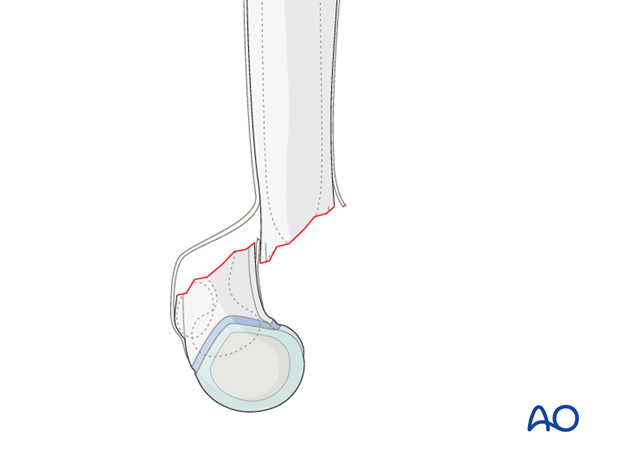

Traction and initial exaggeration of the fracture deformity may be necessary.

If the distal fragment is displaced medially, the medial periosteum will be intact and will be tightened by pronating the flexed forearm after reduction.

If the distal fragment is displaced laterally, the lateral periosteum is likely to be intact and can be tightened after reduction by supinating the flexed forearm.

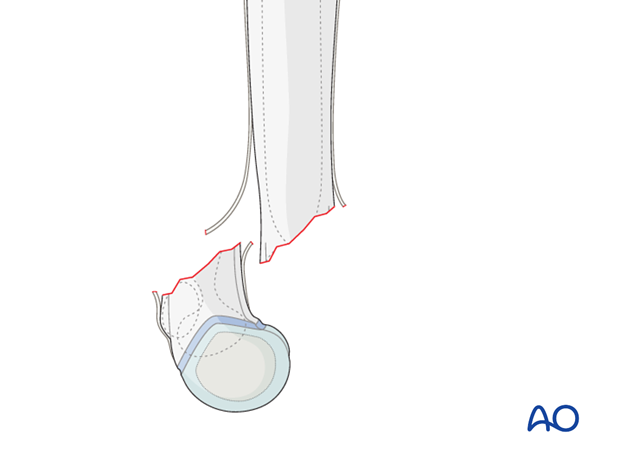

If the distal fragment is displaced anteriorly, the posterior periosteum is likely to be torn. This is a flexion type supracondylar fracture, which occurs in around 5% of all supracondylar humeral fractures.

A significantly posteriorly displaced (extension) supracondylar fracture may rarely also have a torn posterior periosteum.

In such a case, there is no longer significant contact between the main fracture surfaces and this constitutes, by definition, a 13-M/3.1 IV fracture.

This type of fracture is likely to behave in a multidirectionally unstable manner and may require modifications in the reduction and the pinning technique.

Closed reduction is still possible for some of these fractures, but an open reduction may be needed if markedly unstable.

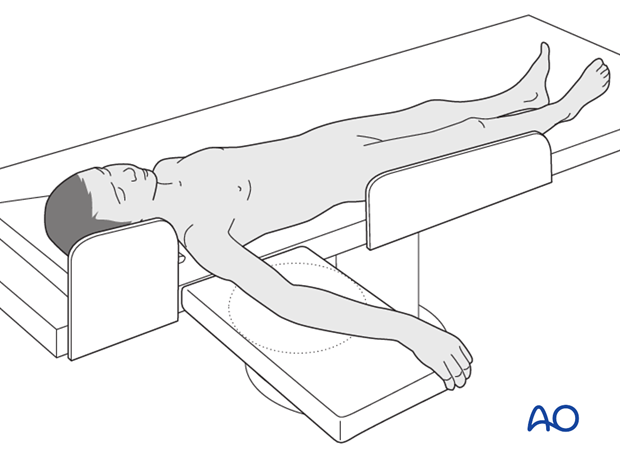

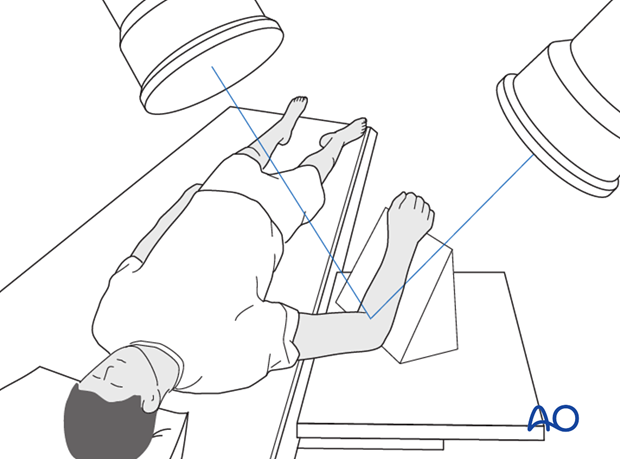

2. Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

3. Closed reduction of fractures with distal fragment posterior to the shaft

Soft tissue reduction

Prior to attempting to reduce the fracture, the soft-tissue shortening and soft-tissue reduction need to be addressed.

A careful inspection of the soft tissues is performed to look for:

- The degree of swelling

- The position of the humeral shaft relative to the muscles (? buttonholed anteriorly)

- Tethering of the dermis over the humeral shaft (“pucker sign”)

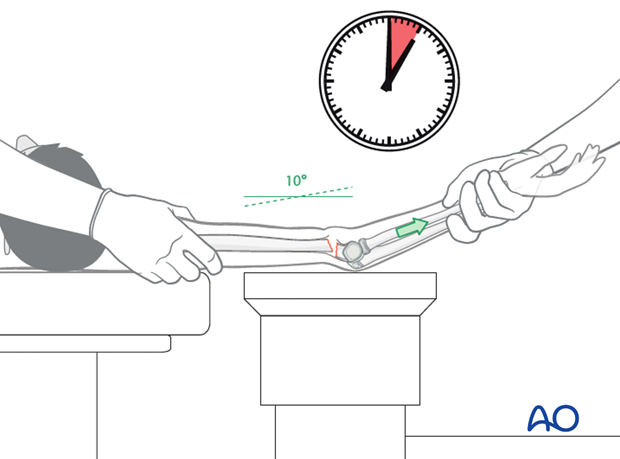

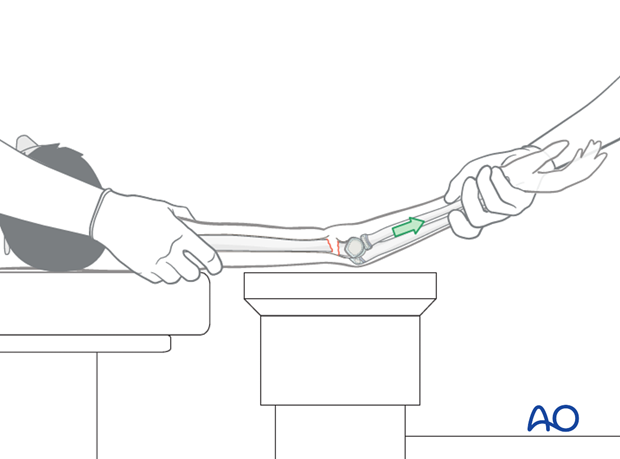

A period of gentle, but sustained, preliminary traction, maintained for 5-10 minutes, is performed.

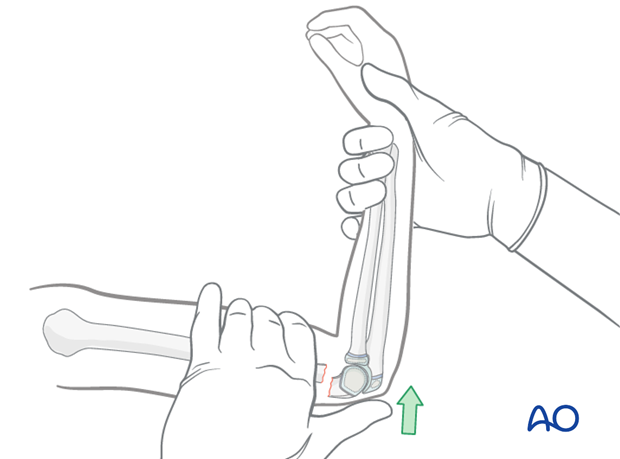

To apply traction, the arm is extended to approximately 10° short of full extension. With an assistant supporting the proximal humerus, progressive traction is applied at the wrist.

The goal of this maneuver is to disengage the humeral shaft from the anterior muscles and skin, in order to allow accurate reduction of the bony fragments.

A palpable soft tissue reduction event will often be felt during the application of traction.

The pucker sign, if present, will visibly reduce with successful traction.

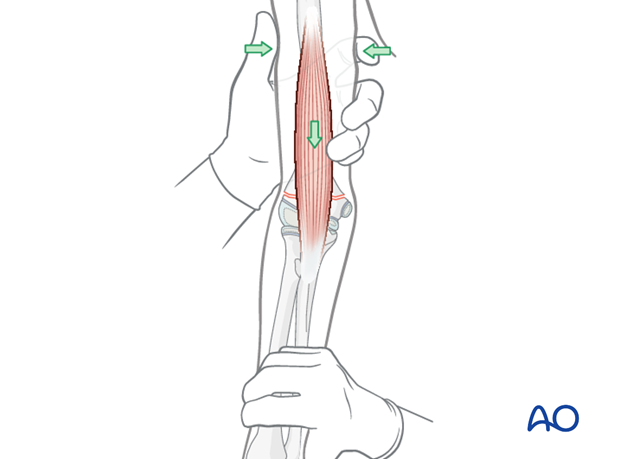

Pearl: If the muscle is stuck despite traction, a milking maneuver can be attempted.

Starting proximally just below the humeral head, the brachialis muscle is gently and repeatedly "milked" distally and anteriorly in order to liberate the soft tissues from around the protruding proximal fragment.

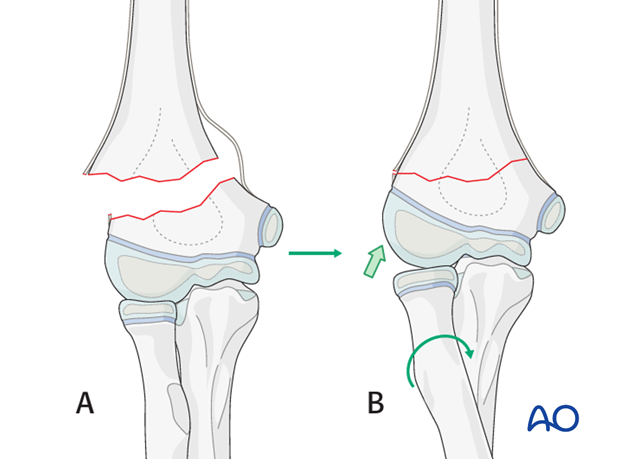

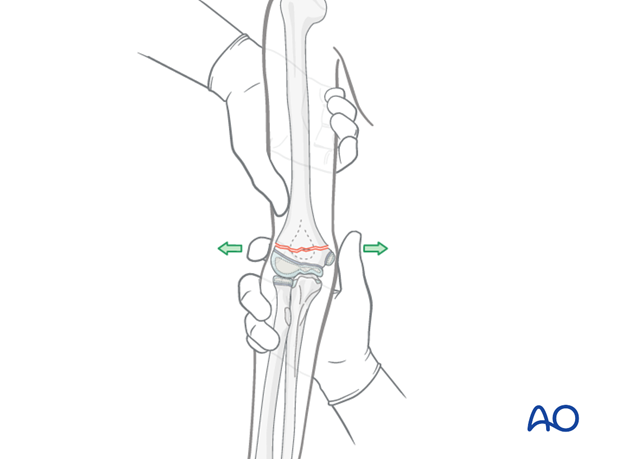

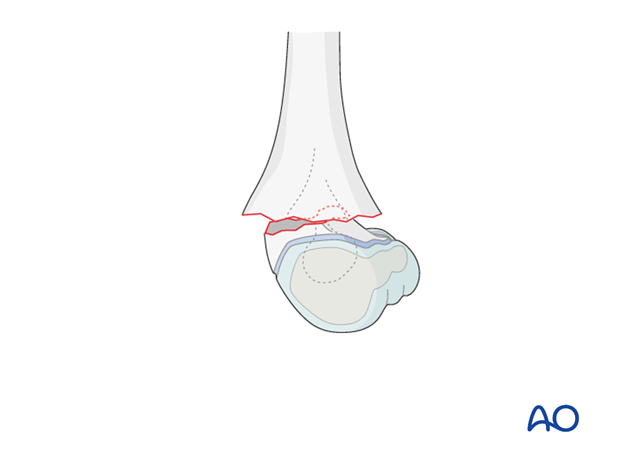

Correction of medial/lateral translation and varus/valgus deformity

The AP view is assessed using image intensification.

- Assess medial, or lateral, translation

- Assess varus, or valgus

Angulation and translation are corrected by direct manipulation. This is usually performed with a thumb and index finger on the medial and lateral epicondyles. The correction is verified using image intensification.

Correction of any persistent internal, or external, rotation, noted on the initial x-rays and suggested by persistent mismatch of the supracondylar ridges, should also be performed at this point.

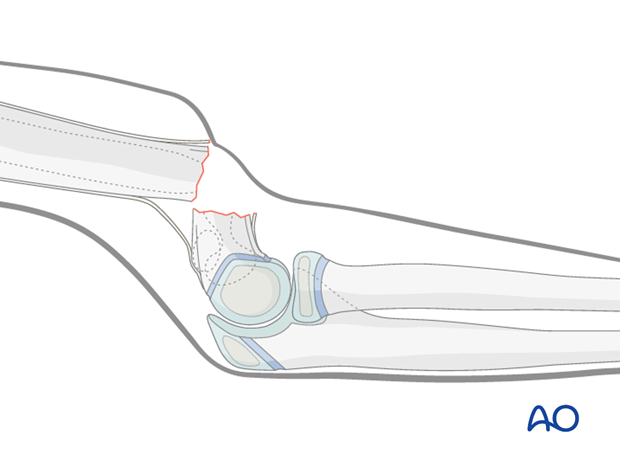

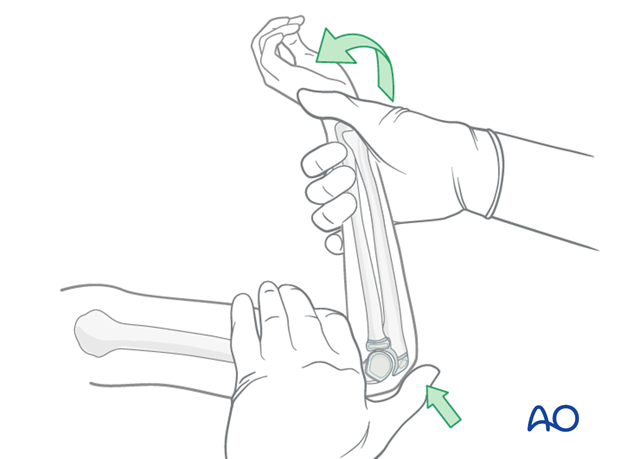

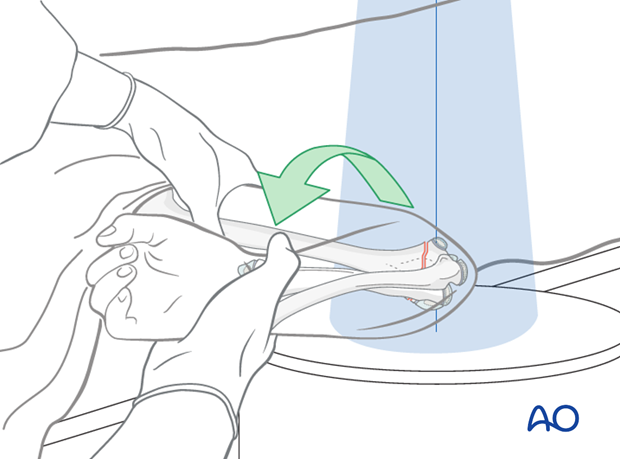

Correction of posterior translation and angulation (apex anterior) deformity

With the elbow initially extended, a thumb is positioned over the olecranon and pushed distally and anteriorly, whilst the elbow is smoothly flexed. If the elbow will not flex fully it is likely that the reduction is incomplete. A complete reduction may be felt.

Note: Avoid direct anterior pressure on the antecubital fossa during this maneuver.

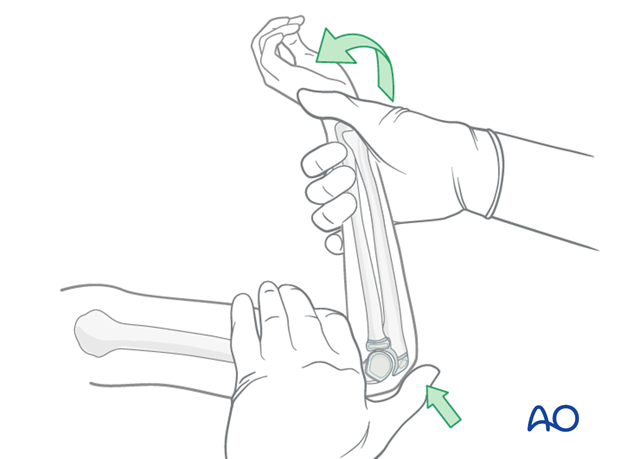

If a complete reduction can be felt, the arm is fully pronated (in case of a medially displaced distal fragment) ,or supinated (in case of laterally displaced distal fragment).

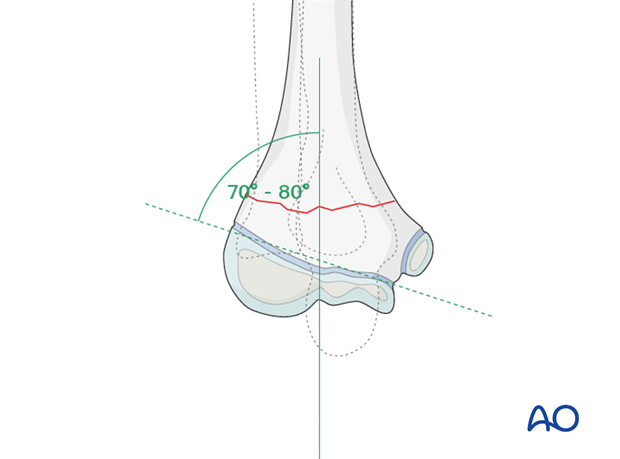

The elbow is maintained in maximal possible flexion and the reduction is verified on an AP image. Baumann's angle should be correct (70-80°) and equal to the uninjured side,at this stage.

Visually evident varus malposition should not be accepted. The carrying angle should be equal to the opposite arm.

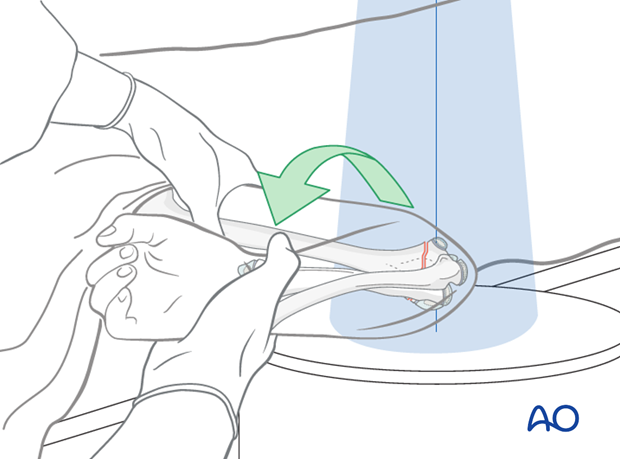

The reduction, including rotational correction, is verified on a lateral view taken by externally rotating the whole arm as a unit.

Often, the reduction will need to be repeated if the distal fragment remains posterior. Numerous attempts at reduction are inadvisable and the surgeon must exercise judgment and decide when to abandon closed manipulative reduction and opt for an alternative solution (open reduction, traction, external fixation, or acceptance of some residual deformity).

Small refinements to the reduction may be undertaken, until satisfactory images are obtained.

Anatomical closed reduction is often obtained, although somewhat less likely in 13-M/3.1 IV fractures.

A minimal amount of medial, or lateral, translation, posterior translation, and/or extension can be accepted, but they make intraosseous pinning more difficult.

If the fragment is translated anteriorly after this reduction maneuver, it is likely that the posterior periosteum is no longer intact and that the fracture will behave as a multidirectionally unstable fracture.

This type of fracture may require a modified reduction technique as described below.

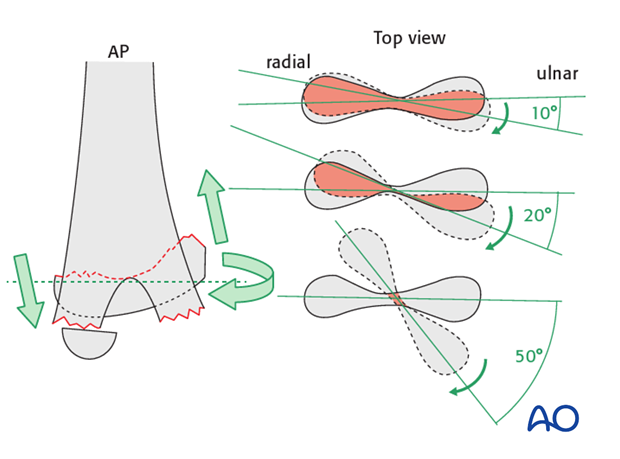

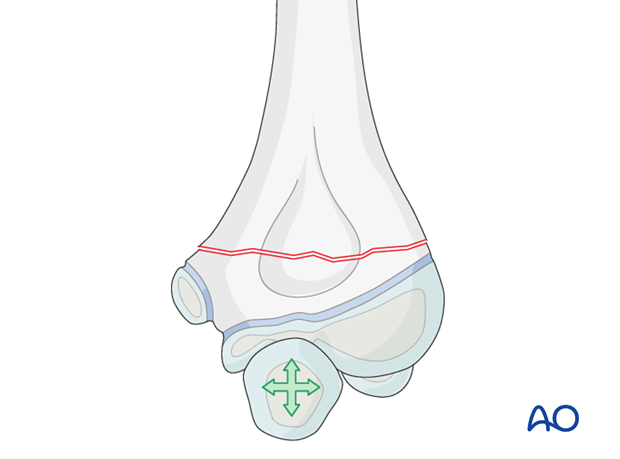

Correction of rotational deformity

Rotational malalignment may also require adjustment.

Rotational malalignment is best visualized on the lateral image intensifier view.

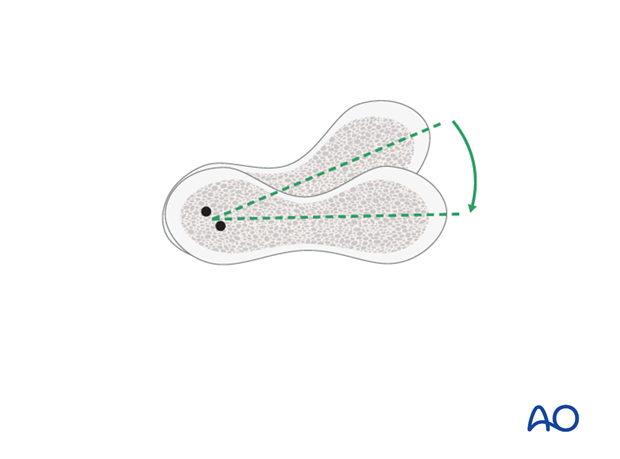

Apparent mismatch between the width of the proximal and distal fragments demonstrates that rotational malalignment is still present.

Oblique (column) views are useful in determining whether the distal fragment is internally or externally rotated.

The most common residual rotation is internal rotation of the distal fragment with the medial side of this fragment posterior to the shaft fragment.

This residual rotation should be identified and corrected, otherwise it may result in medial shortening and a varus malposition, as well as the impossibility of inserting intraosseous wires.

Restoration of the hourglass appearance of the olecranon fossa on the lateral view is a good indication that correct rotational alignment has been obtained.

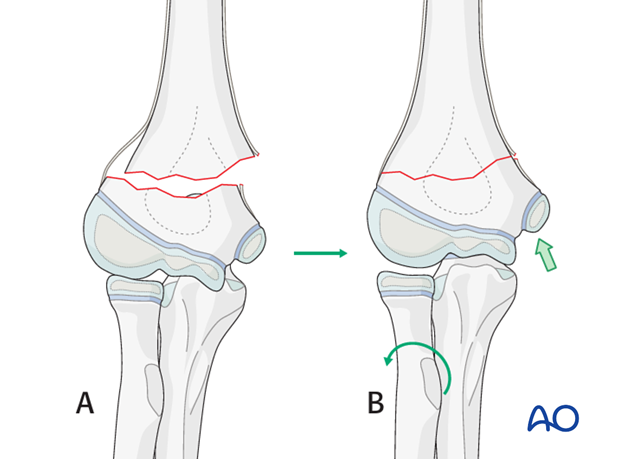

4. Closed reduction of fractures with ruptured posterior periosteum

Ruptured posterior periosteum occurs in three clinical settings:

- Flexion type supracondylar fractures

- Significantly displaced extension type supracondylar fractures in which the entire periosteum sleeve is torn at the time of injury - 13-M/3.1 IV injuries

- Extension type supracondylar fractures where the surgeon inadvertently tears the posterior periosteum during the reduction

No single closed reduction technique will be universally successful and the following modifications of the closed reduction technique will help in the majority of these settings.

Reduction maneuver

Strong traction and forceful maneuvers are not recommended as they may cause additional soft tissue damage.

Gentle direct manipulation of the distal fragment with control by image intensification will allow determination of improvements of reduction and, therefore, stability.

Reduction will often be lost when rotating the arm to obtain a lateral image.

Moving the image intensifier between AP and lateral positions, as needed, is recommended in such instances.

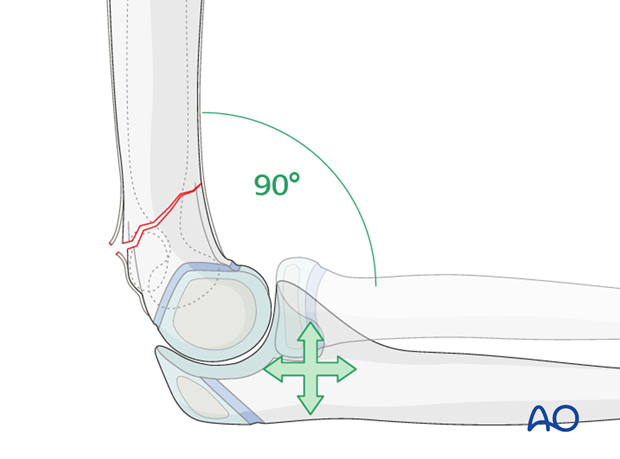

Flexing the elbow to 90° and using the ulna to indirectly control the distal fragment can be useful in obtaining reduction.

The ulna can be used to correct anterior/posterior and medial/lateral translations.

For some patients, similar maneuvers, but with the elbow closer to full extension can be successful.

Pronation of the forearm flexed to 90° will correct varus.

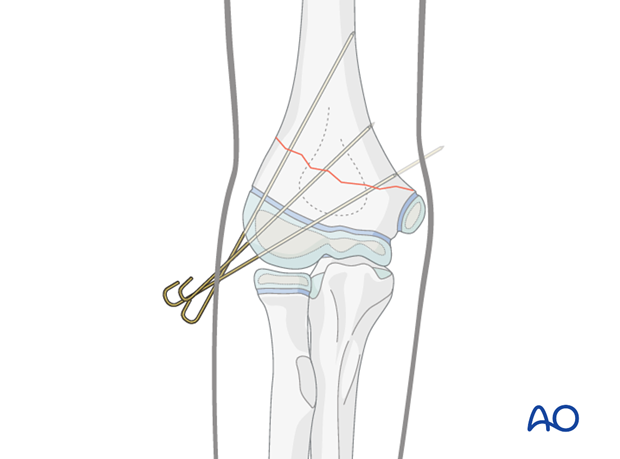

Pearl: Use of K-wire to aid reduction

Once a preliminary reduction, albeit unstable, has been obtained, an initial K-wire can be inserted within the lateral column of the distal fragment.

This can then be used as a lever/joystick to improve the reduction and advanced across the fracture line. The definitive K-wires can then be inserted and the joystick wire removed, as necessary.

5. Fixation

General guidelines for K-wire insertion

2.0 mm K-wires are used for most supracondylar fractures in larger children (usually above 6 years of age).

1.6 mm K-wires may be used for smaller and younger children.

It is preferable to insert all K-wires from the lateral side to avoid the risk of an iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury.

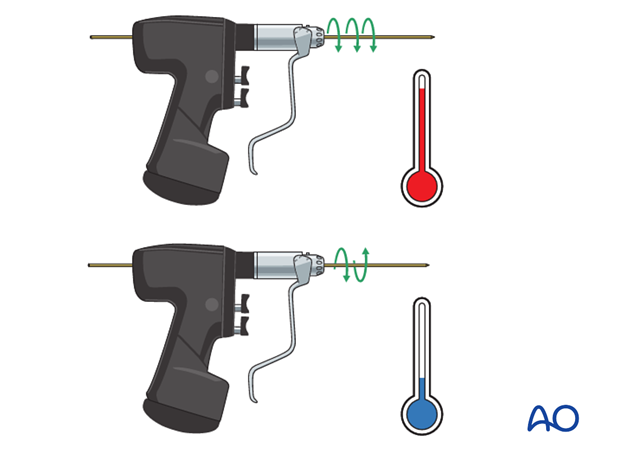

All K-wires should be sharp-pointed. Powered insertion of K-wires generates heat in the tissues: wires should be inserted with a slow-running drill, an oscillating drill, or by hand.

If multiple attempts are made to insert any one wire, the bone may be weakened or the physis may be damaged. In general, only two attempts at insertion of any one K-wire are permissible.

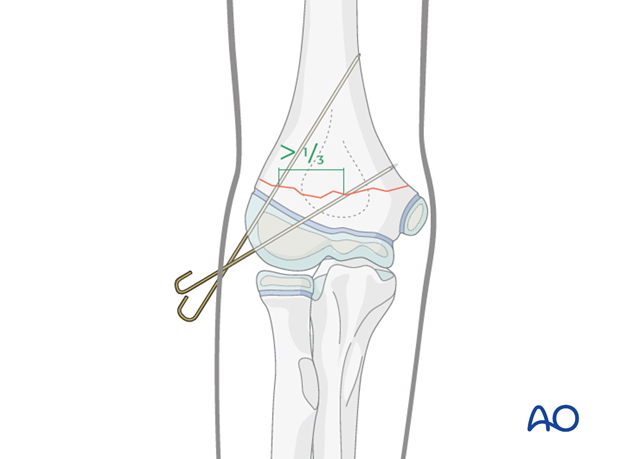

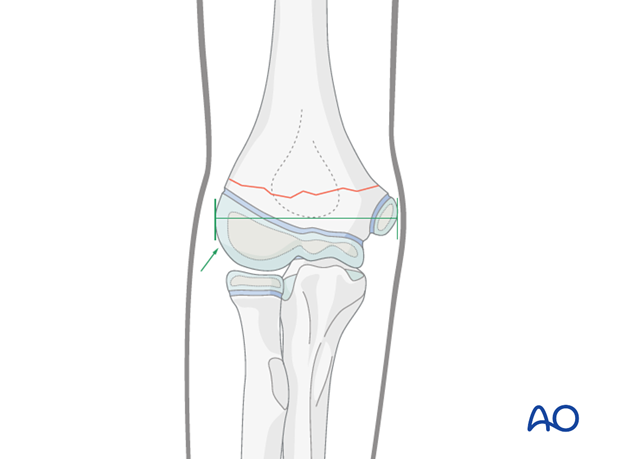

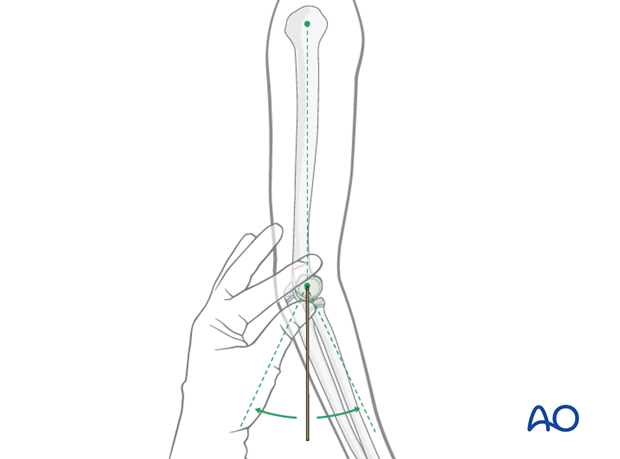

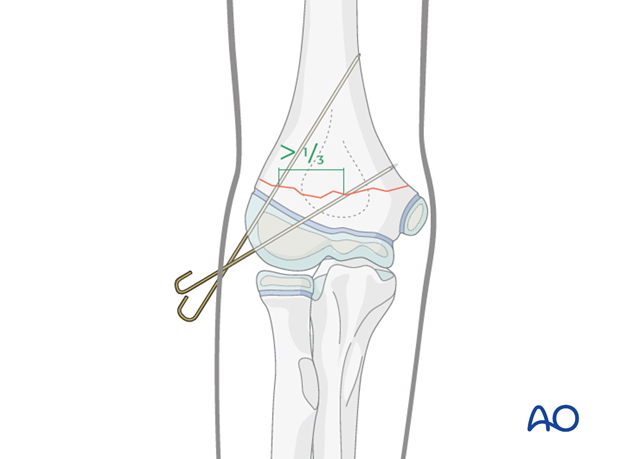

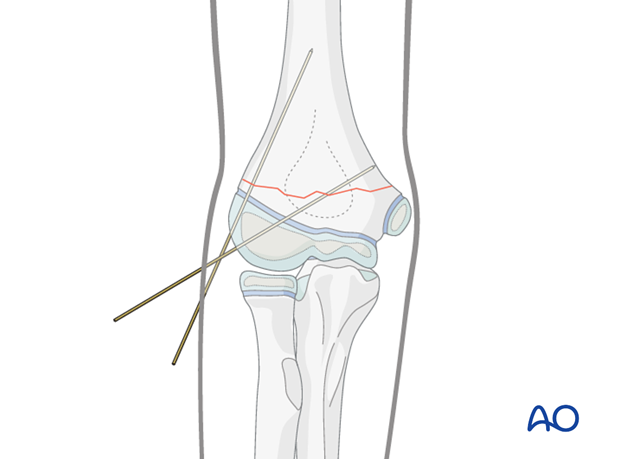

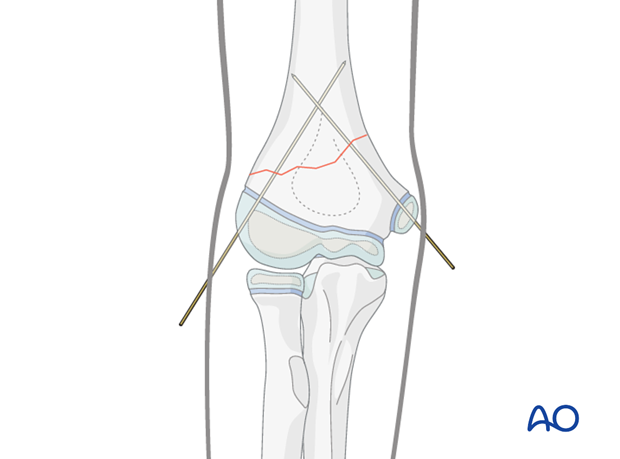

The pins must diverge to provide adequate spread at the fracture site on the AP view.

Adequate spread is obtained if both the medial and lateral columns contain at least one pin, or if the divergence of the pins exceeds 1/3 of the width of the fracture.

If the pin spread is inadequate, the fixation will be likely to be rotationally unstable.

The tendency, in this case, is for the distal fragment to internally rotate and this allows collapse into varus, resulting in a cosmetically unappealing malunion.

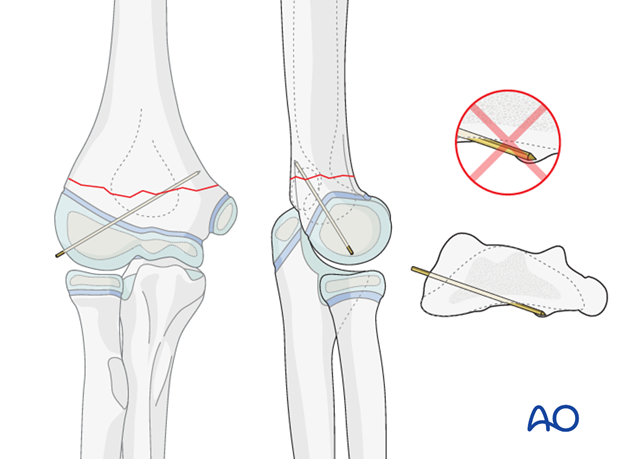

Oblique fractures high on the lateral side

This fracture pattern is anatomically favorable for the insertion of two, or even three, lateral pins. A medial pin would only rarely be required.

The pin insertion is performed as described below for the transverse fracture pattern.

Transverse fractures

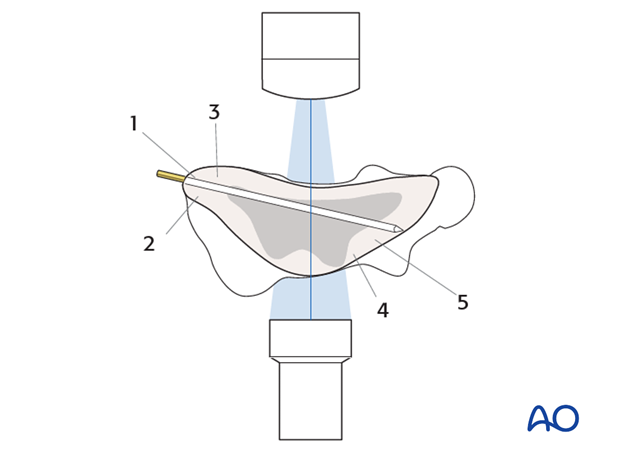

Pin entry points are located in the lateral humeral condyle, distal to its maximal width.

Any intraosseous pin will penetrate the following structures in sequence:

- Epiphyseal cartilage (or ossific center)

- Physis

- Metaphyseal bone of the distal fragment

- Metaphyseal bone of the proximal fragment

- Cortex of the proximal fragment

Note: Tactile feedback during pin insertion is important confirmation of intraosseous position of the pin.

AP image intensifier views are used to monitor K-wire insertion.

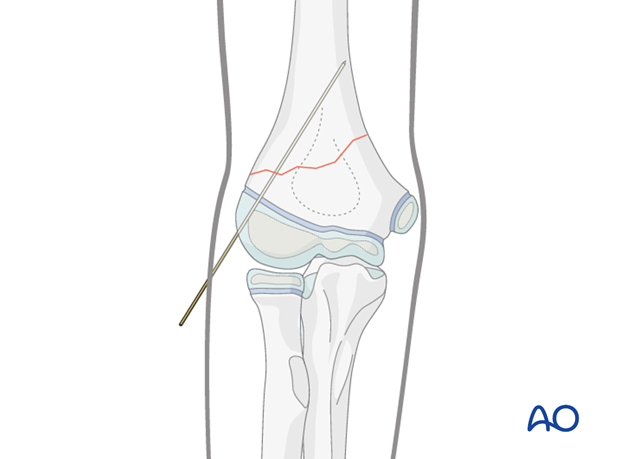

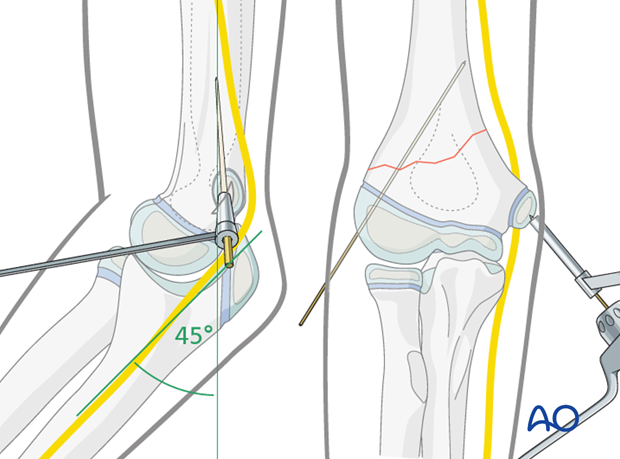

The first K-wire is inserted within the lateral column and should achieve strong purchase in the medial cortex of the proximal fragment. It can either engage, or just penetrate, this cortex.

Engagement of the cortex can be heard as a change in pitch of the K-wire driver and can be felt by the surgeon inserting the K-wire.

Passage through other dense bony structures, e.g., olecranon fossa cortex, may also be felt.

The surgeon should pay attention to correspondence between feedback from the K-wire driver and what is seen on the image intensifier.

The position of the first K-wire is confirmed on both AP and lateral views, the latter by gently externally rotating the arm as a unit.

Techniques to assist correct insertion of the pin within the sagittal plane (lateral view) include:

- Identifying the alignment of the humeral shaft when evaluating the reduction and marking the sagittal alignment on the skin

- Palpation of the humeral head aiming the pin for its center

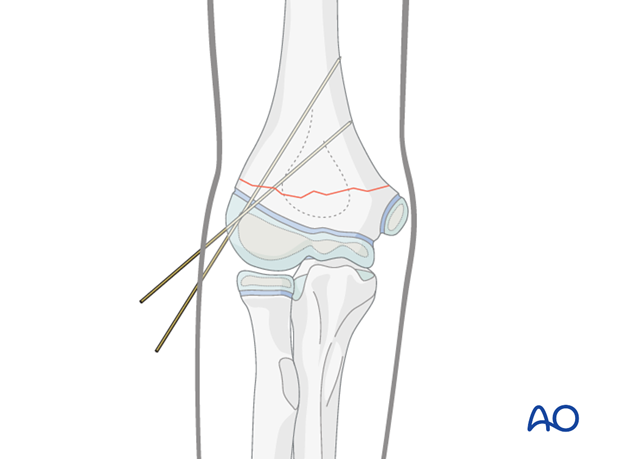

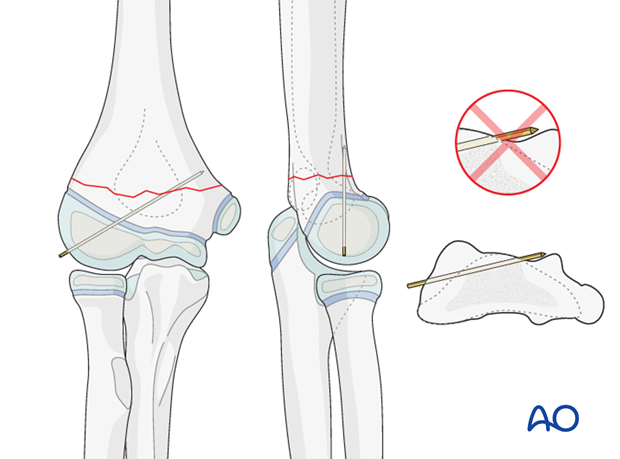

The second K-wire is inserted from the lateral side into the medial column through the capitellar secondary ossification center.

The pin spread at the fracture site should be more than 1/3 of the bone diameter.

The AP image can be used as a guide for aiming.

Care must be taken that the K-wire achieves purchase in the proximal fragment.

The audible and tactile feedback from the K-wire driver must be used since it is possible to miss the proximal fragment anteriorly…

…or posteriorly, and not notice it on the lateral image.

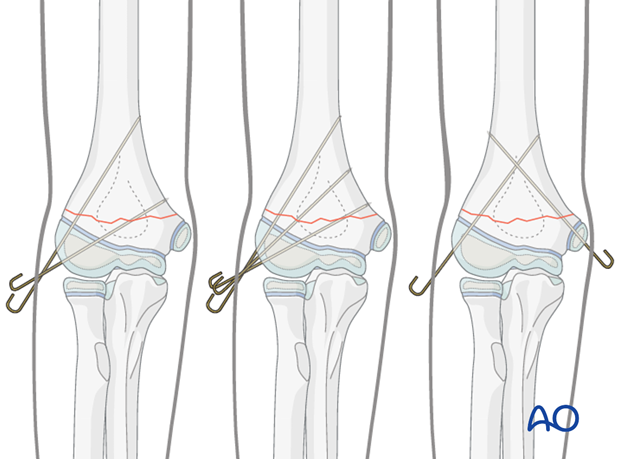

Following insertion of the second K-wire, AP, lateral, and column (45° internal and 45° external) views are obtained.

K-wire position must be adjusted if necessary.

If the reduction and fixation are satisfactory, lateral real-time image intensification, with flexion and extension of the elbow, can be used to confirm fixation stability.

If the K-wire spread is inadequate in the AP view (less than 1/3 of the bone diameter), or if the fixation is deemed insufficiently stable, a third K-wire should be inserted.

Oblique fractures high on the medial side

The technique of medial K-wire insertion described below should be followed whenever at the surgeon's discretion medial intraosseous wiring is performed.

This fracture pattern is anatomically unfavorable for pinning from the lateral side alone. It may not be possible to achieve adequate fixation of both columns, or adequate pin spread, with lateral pins alone. In this case, the addition of a medial pin may be necessary.

The first lateral pin is inserted as described above.

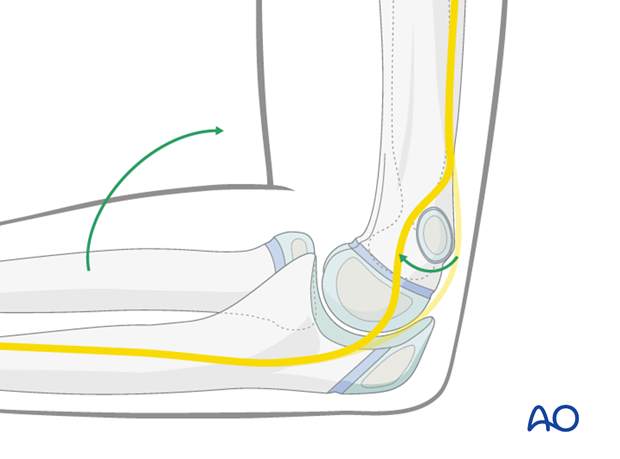

Pitfall: Iatrogenic injury to the ulnar nerve occurs in up to 6% of medial pinnings.

Howard A, Melpuri K, Abel MF, et al. The treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures - Evidence based guideline and evidence support. North River road: AAOS; 2011.)

In many children the ulnar nerve can sublux forwards onto, or anterior to, the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.

This may be easier to demonstrate on the contralateral, uninjured elbow and is difficult to appreciate in a swollen and injured limb.

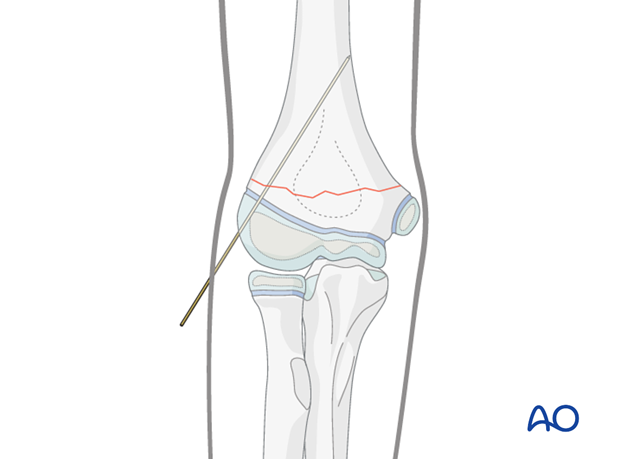

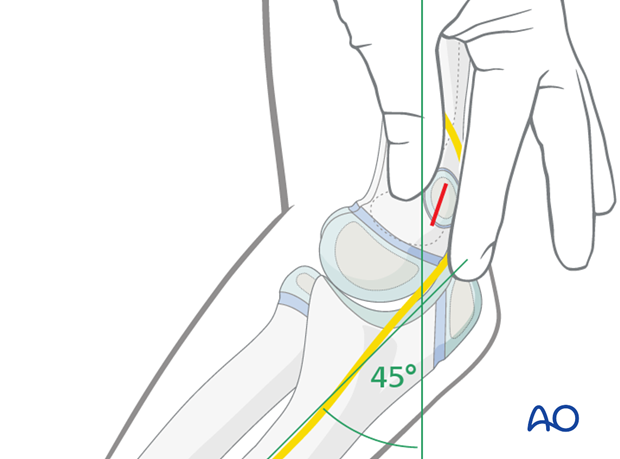

To minimize risk to the ulnar nerve, the medial pin is inserted with the arm in the position in which it will be immobilized (around 45° flexion) and a limited open technique is used to guard the ulnar nerve.

The medial epicondyle is palpated (this can be difficult in a swollen elbow).

A 1 cm longitudinal skin incision is made directly over the prominence of the medial epicondyle.

Blunt dissection is performed, until the medial epicondyle can be palpated and seen.

A 2.0 mm drill guide, placed directly onto the medial epicondyle, is used to establish the entry point of the K-wire.

The K-wire is inserted through the medial epicondyle and across the fracture in the medial column.

Attention should be paid to the audible and tactile feedback from the K-wire driver as the K-wire engages the lateral cortex of the proximal fragment.

Following insertion of the medial K-wire, AP, lateral and column (45° internal and 45° external) views are obtained.

K-wire position must be adjusted if necessary.

If the reduction and fixation are satisfactory, lateral real-time image intensification, with flexion and extension of the elbow, can be used to confirm fixation stability.

Note

Most stable pin configurations will use two or three lateral entry pins.

Occasionally a medially inserted pin may be required.

Image intensification is used to confirm that the reduction and pin fixation are satisfactory and that the construct is stable.

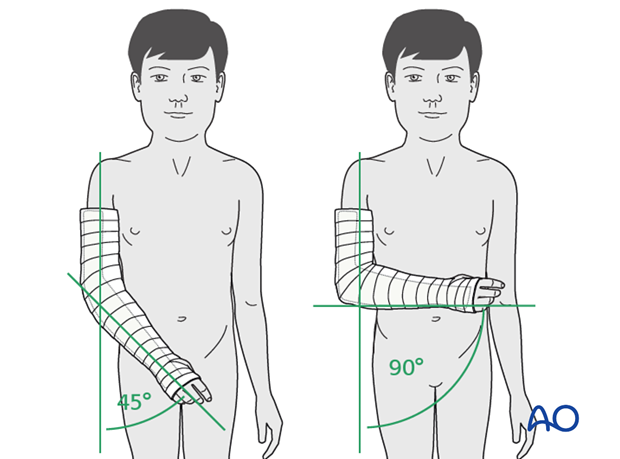

6. Immobilization

The arm is protected with a posterior plaster splint, applied at 45°–90° of flexion, depending on local protocol, for approximately three weeks.

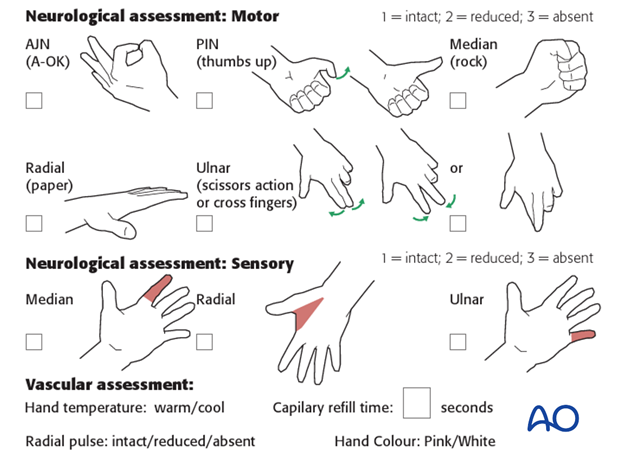

Neurological and vascular function is checked postoperatively.

Pins are usually removed in the clinic 3–4 weeks after insertion.

For the first few days, the elbow and forearm can be elevated on a pillow, until swelling decreases and comfort returns.

At this point, the child may choose to use a sling to support the arm. Many children are more comfortable without a sling.

7. Aftercare

Supracondylar humeral fractures heal rapidly and often within 3–5 weeks.

Analgesia, including ibuprofen and paracetamol, should be administered regularly.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a possible early postoperative complication that may be difficult to diagnose in younger children.

The child should be examined frequently, to ensure finger range of motion is comfortable and adequate.

Neurological and vascular examination should also be performed.

Increasing pain, decreasing range of finger motion, or deteriorating neurovascular signs should prompt consideration of compartment syndrome.

See also the additional material on postoperative infections.

Discharge care

When the child is discharged from the hospital, the parent/caregiver should be taught how to assess the limb.

They should also be advised to return if there is increased pain or decreased range of finger motion.

It is important to provide parents with the following additional information:

- The warning signs of compartment syndrome, circulatory problems and neurological deterioration

- Hospital telephone number

- Information brochure

Follow-up x-rays

Control x-rays may be taken at one week following injury to assess fracture position. Further x-rays may be necessary at three weeks to assess fracture healing. This should be performed after the splint has been removed.

Removal of cast or splint

Splints or casts are usually removed 3 weeks of the injury.

K-wire removal

Protruding K-wires can be removed in the clinic, without anesthesia.

A simple sling can be provided for comfort.

Recovery of motion

As symptoms recover, the child should be encouraged to remove the sling and begin active movements of the elbow.

The majority of elbow motion is recovered rapidly, usually within two months of splint removal. The older child may take a little longer.

Once the child is comfortable, with a nearly complete range of motion, he/she may resume noncontact sports incrementally. Resumption of unrestricted physical activity is a matter of judgment for the treating surgeon.