Closed reduction; long arm cast

1. Introduction

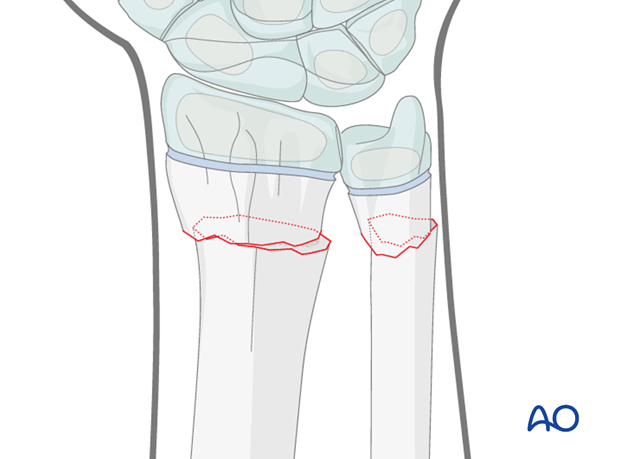

These fractures are usually posteriorly angulated (apex anterior) and can generally be reduced closed, ideally under general anesthesia. Impediments to reduction include interposed periosteum and pronator quadratus.

Anteriorly angulated (apex posterior) fractures are less common and are also generally reduced closed. Impediments to reduction include the extensor tendons.

Most of these fractures are stable after reduction and do not require fixation, particularly in younger children. In children approaching skeletal maturity instability after reduction becomes more likely.

2. Patient preparation

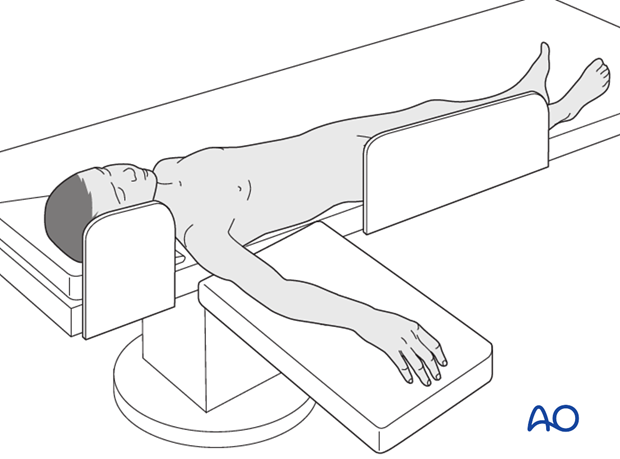

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

3. Anatomy of the distal forearm

A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the wrist is essential.

The additional material gives a short introduction.

4. Reduction

Indirect reduction of partially displaced, posteriorly angulated fractures

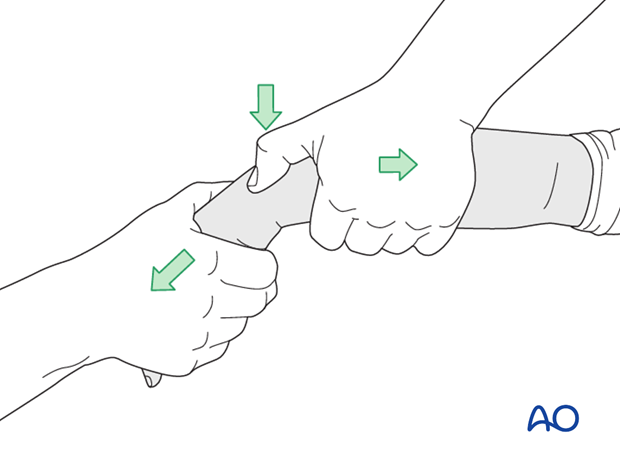

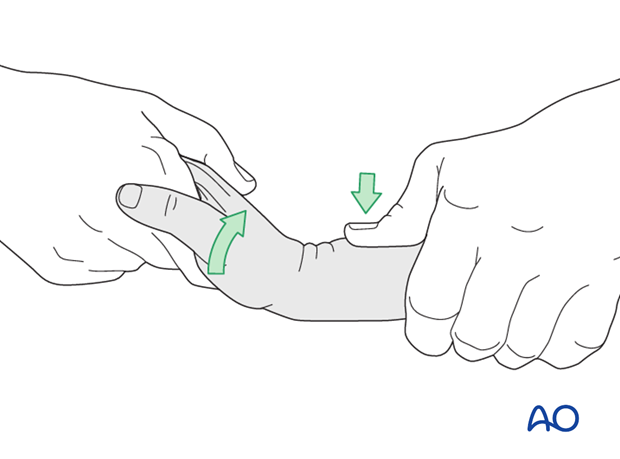

The reduction maneuver for posteriorly angulated fractures, together with some posterior translation (common) is by traction and direct pressure over the epiphysis, followed by palmarflexion.

Ideally, the reduction is verified with image intensification and any residual malalignment is corrected with direct pressure.

Indirect reduction of partially displaced, anteriorly angulated fractures

The reduction maneuver for anteriorly angulated fractures, together with some anterior translation (uncommon) is by traction and direct pressure over the epiphysis, followed by dorsiflexion.

Ideally, the reduction is verified with image intensification and any residual malalignment is corrected with direct pressure.

Indirect reduction of completely posteriorly displaced fractures

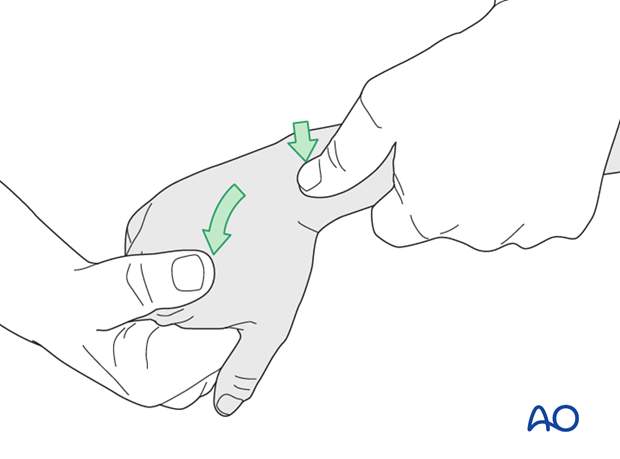

For completely displaced fractures, direct pressure is applied to the epiphysis with the wrist in hyper dorsiflexion.

Following this, the fracture is reduced by palmarflexion (whilst continuously applying direct pressure to the epiphysis).

Once the radius has been reduced the ulna will also usually reduce.

Ideally, this should be confirmed using image intensification.

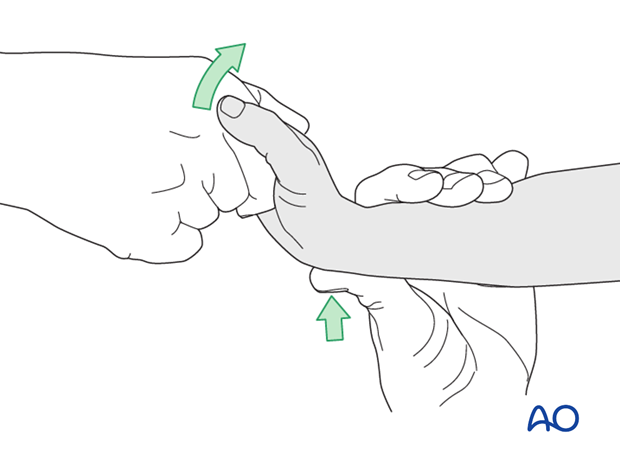

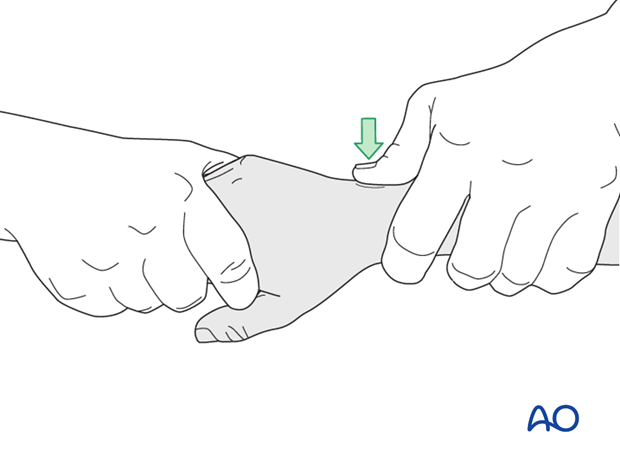

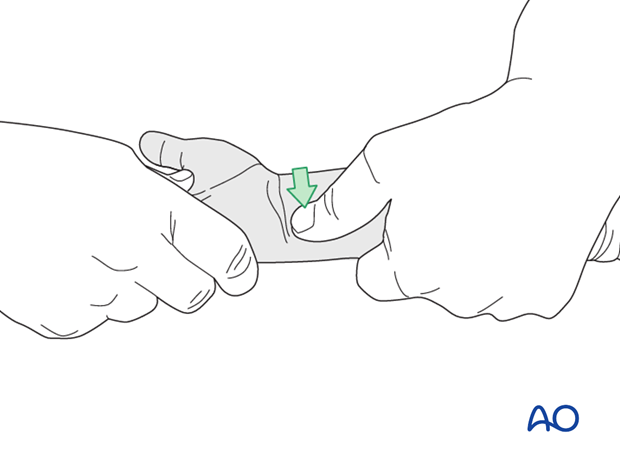

In case of persistent malreduction of the ulna, direct pressure on either the posterior…

…or anterior surface should produce an anatomical reduction.

Reduction is often more straightforward than single bone fractures, and may not require K-wire fixation, if stable. Relaxing the manual reduction pressure, will determine whether it is stable, as an unstable reduction will redisplace.

See:

- Zamzam MM, Khoshhal KI. Displaced fracture of the distal radius in children: factors responsible for redisplacement after closed reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 Jun;87(6):841-843.

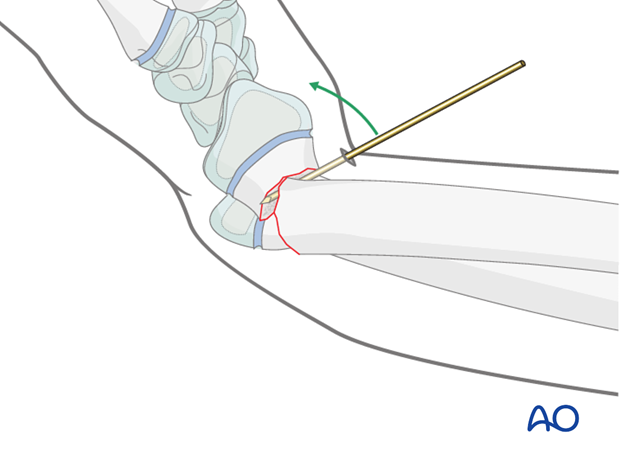

Direct reduction using K-wire

For irreducible fractures, a percutaneous K-wire can be inserted (through a stab incision) into the fracture site and used as a lever to facilitate reduction.

An assistant is required to maintain the reduction throughout the cast application. The presence of the assistant will, however, not be shown in all of the following illustrations.

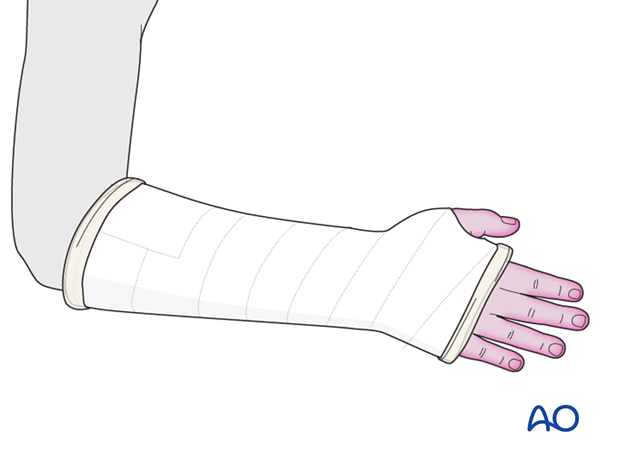

5. Long arm cast

General considerations

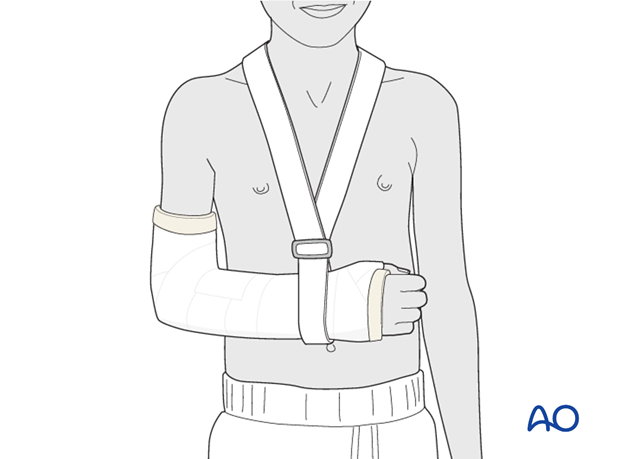

A long arm cast should always be used where it is necessary to control forearm rotation in order to prevent fracture displacement. In very young and in noncompliant children, a long arm cast is preferable even if a short cast would otherwise be appropriate

The long arm cast is applied according to standard procedure:

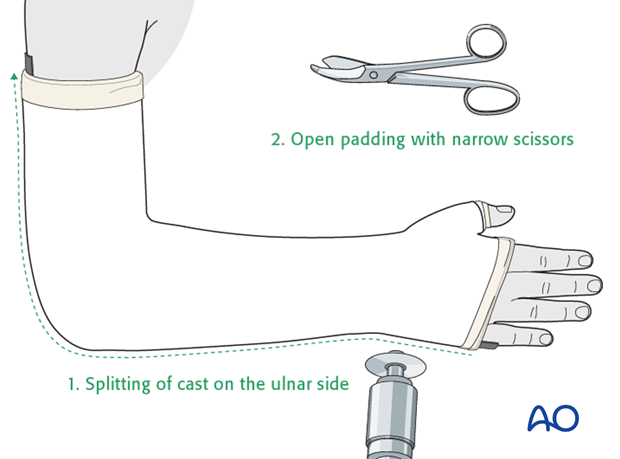

Splitting of cast

If a complete cast is applied in the acute phase after injury, it is safer to split the cast down to skin over its full length.

6. Aftercare

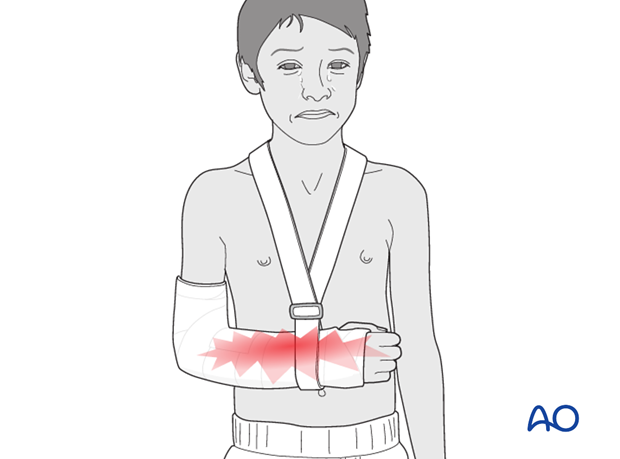

Tight cast

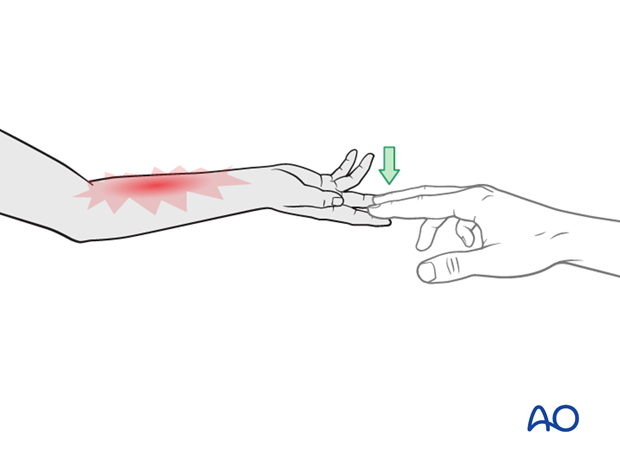

Further swelling in a restricting cast can cause pain, venous congestion in the fingers and occasionally a compartment syndrome.

For this reason any complete cast applied in acute phase should be split down to skin.

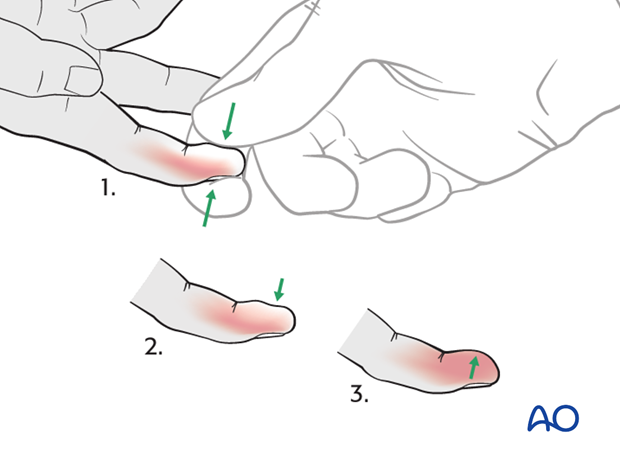

Parents/carers should be instructed how to detect circulatory problems by pressing and releasing the fingertips and watching if the blood flow/color returns to normal (capillary refill), compared to the opposite hand.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is an unusual but serious complication after the application of a complete cast and can be difficult to diagnose, especially in younger children. Neurological signs appear late and the main sign is excessive pain on passive extension of the fingers.

It is important to make sure that the parents/carers are aware of the risk of compartment syndrome.

The parents/carers and patient should be informed to take note of increased pain and/or unresponsiveness to normal painkillers.

They should know that this may indicate serious complications. It is important for them to detect these signs as early as possible and report them urgently to the surgeon/nurse by telephone, or to attend the Emergency Room (ER) without delay.

Nerve compression is an occasional complication and the signs include:

- Sensory deficits (numbness)

- Weakness of active finger movement

- Paresthesia (tingling)

Infections

See also the additional material on postoperative infections.

Cast care

If a normal plaster of Paris cast is used, it is important to keep the cast clean and dry in order to maintain the reduction.

When the swelling has reduced, the cast can become loose. The loss of support can result in loss of reduction.

In this circumstance, the parents/carers are advised to return to the healthcare provider.

Follow-up x-rays

Depending on the fracture pattern, the age of the child and the method of treatment, the patient has to return for follow-up x-rays to monitor the fracture position.

X-rays taken for fracture position can be taken with cast in place. Any x-rays to assess the state of bone healing must be taken without the cast and correlated with clinical examination.

In most cases, it is conventional to obtain follow-up x-rays after reduction to ensure that the position is maintained.

In general, in the child below 5 years of age, the follow-up is usually about 4-5 days after reduction. In the older child with a potentially unstable fracture, an x-ray would normally be taken at 7-10 days.

Further follow-up x-ray is a matter of clinical judgement, the responsibility of the treating surgeon, and tends to be longer in older children (see also Healing times).

For complete fractures of the metaphysis, redisplacement after reduction is not uncommon. It is therefore, important to take early follow-up x-rays in order to detect a possible redisplacement.

See also the additional material on posttraumatic growth disturbances.