Repair of coronoid fracture

1. General considerations

Repair depends on the morphology of the coronoid fracture:

- Lasso suture repair for small and multifragmentary coronoid (tip) fractures

- Fixation with anterior buttress plate with/without additional lag screw(s) for larger coronoid tip and anteromedial facet fractures

- Lag screw fixation with/without posterior plate for basilar coronoid fractures associated with olecranon fracture dislocations

Preliminary remark

Isolated coronoid fractures are extremely rare and when seen, suspect a spontaneously reduced dislocation and look for elbow instability. The coronoid is almost always fractured in association with a dislocation of the ulnohumeral joint or a more complex proximal ulna or olecranon fracture. Repair of a – even small – coronoid fracture may be necessary for restoring elbow joint stability.

Coronoid fractures occur in several patterns (described below). They must be assessed with care.

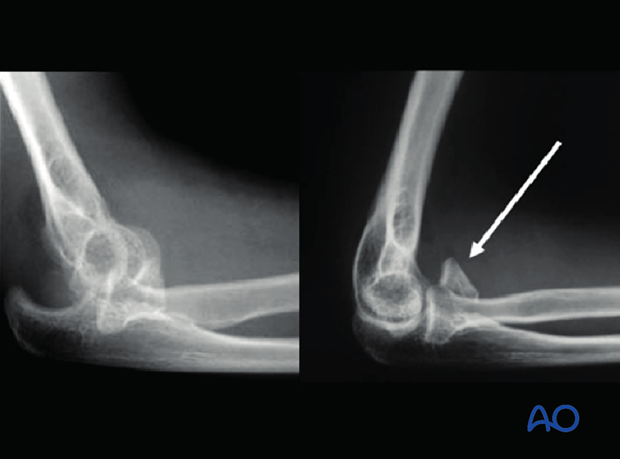

Fragments which appear small on a lateral x-ray may be larger than suspected. A CT is warranted to better determine the fragment’s exact size. Particularly deceiving are small anteromedial facet impaction fractures, which may be associated with posteromedial varus instability of the elbow. In general, the larger the coronoid fragment, the greater its potential effect on elbow stability.

The above x-rays, before and after reduction of a dislocated elbow, show a large coronoid fragment, still displaced after the elbow joint is reduced.

Associated ligament injuries

Coronoid fractures are often associated with ligament disruption. Lateral collateral ligament tears should be repaired routinely. The medial collateral ligament may be attached to a large coronoid fragment. Fracture fixation repairs the ligament in this case. Occasionally – with small anteromedial facet fractures and complete elbow dislocation – the medial collateral ligament is avulsed from the medial epicondyle, and it can be repaired.

Reduction

Anatomical reduction of a larger coronoid process fracture is important for elbow joint stability and congruity. This is particularly true when the coronoid fracture is part of a comminuted olecranon fracture. Reduction may be visualized through the medially extended posterior incision, through the olecranon fracture site, or through a lateral incision if a proximal radius fracture can be retracted or an unsalvageable radial head fracture is replaced.

2. Positioning

The patient is placed in a supine position:

3. Approaches

Coronoid fractures may be approached through a lateral approach, through the site of a radial head or neck fracture, or medially. Depending on the fracture configuration, a medial over-the-top, Taylor and Scham, or FCU split approach may be selected. A medial epicondylar osteotomy is another – but seldom used – option. Additionally, coronoid fractures associated with olecranon fractures can sometimes be reduced and fixed via the olecranon fracture site, through a posterolateral approach.

4. Fixation principles according to fracture type

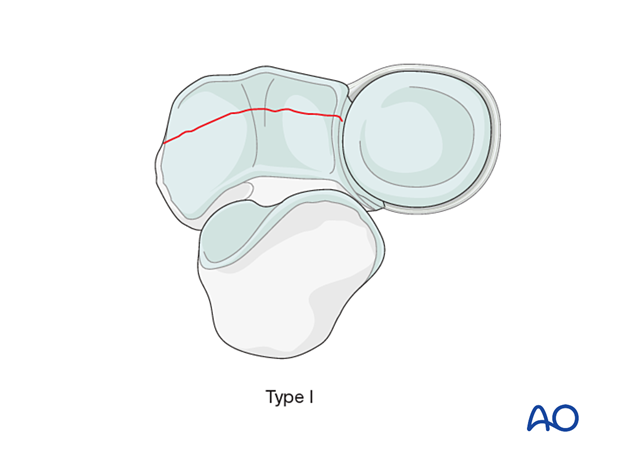

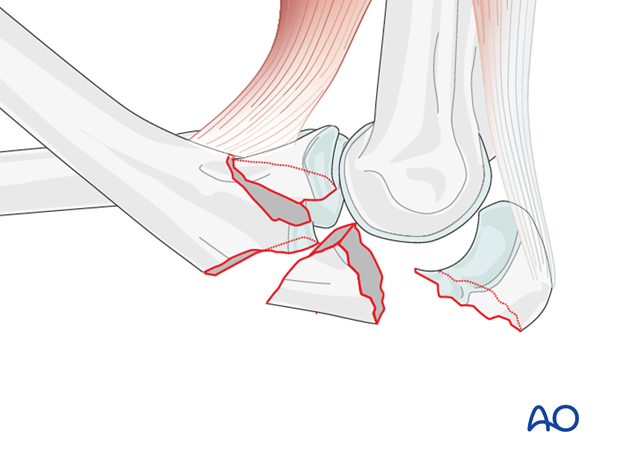

Transverse fractures

Transverse fractures (Mayo/O’Driscoll type I) of the coronoid tip include the capsular attachment and average more than 1/3 of the total coronoid height. They may have smaller or larger bone fragments.

Repair, usually with sutures, is necessary if the elbow is unstable.

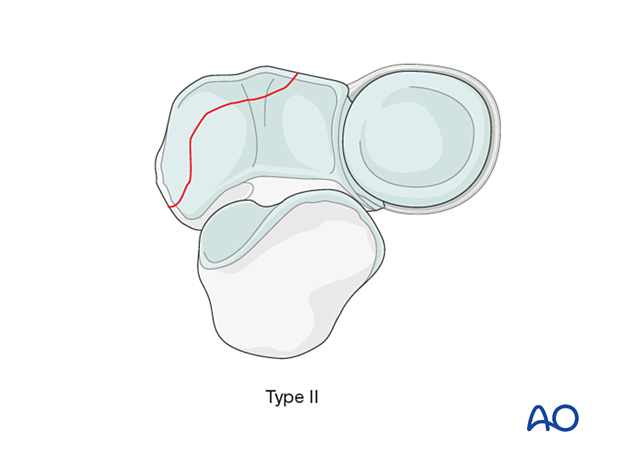

Anteromedial facet fractures

Anteromedial facet fractures (Mayo/O’Driscoll type II) may be small or large.

The small fractures are best repaired with suture reattachment of the capsule through a medial exposure.

Larger fractures may represent an avulsion of the anteromedial facet with the anterior band of the medial collateral ligament attached. This creates varus posteromedial instability. These injuries are best fixed with an anteromedial buttress plate.

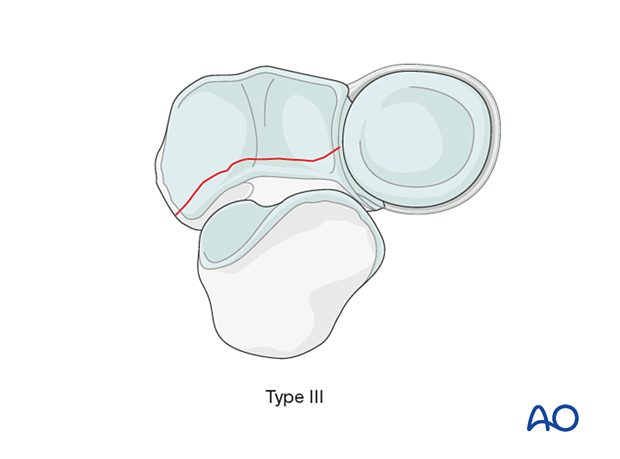

Basilar fractures

Basilar fractures (Mayo/O’Driscoll type III), typically one or two large fragments. These may often be repaired with lag screws through or beside a dorsal plate. A medially extended exposure may be necessary for reduction and fixation. Occasionally, an additional anteromedial plate may be required.

Irreparable coronoid fractures, because of extreme comminution and/or osteoporosis, are occasionally encountered. Restoration of elbow stability may require additional use of a hinged internal or external fixator.

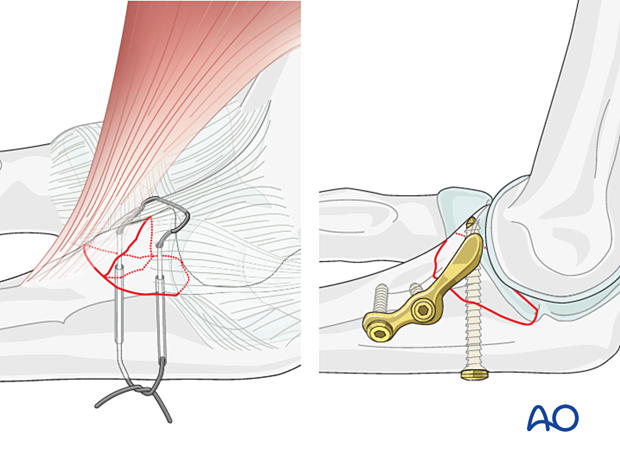

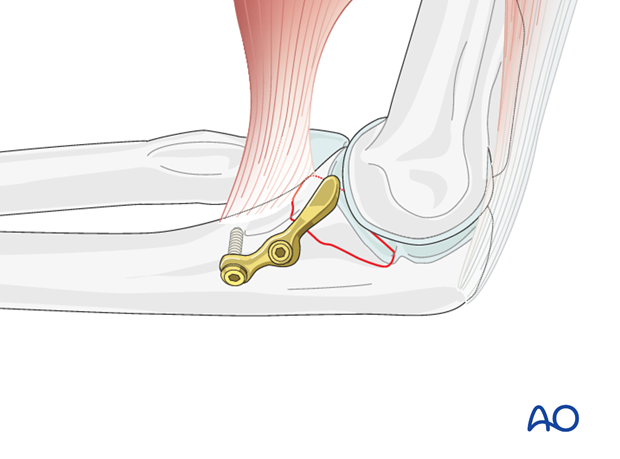

5. Lasso suture repair

Introduction

In small type I and II, and multifragmentary, fractures of the coronoid process, the fragments with joint capsule can be reattached with sutures. For smaller anteromedial fractures, this requires a medial approach.

The sutures are passed through or around the coronoid fragment(s) and, if possible, through the capsule that is attached to it.

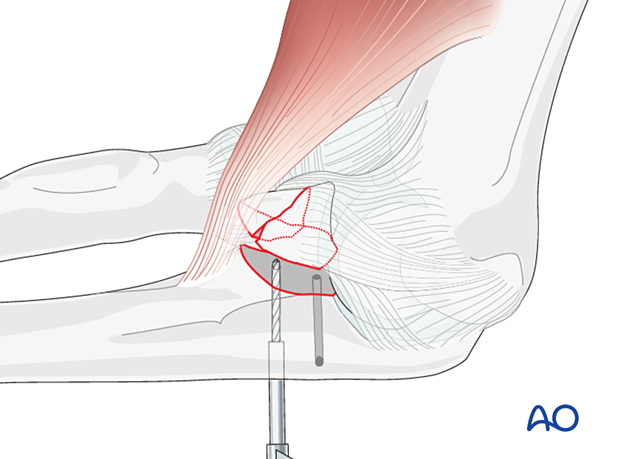

Drilling holes for sutures

Drill two holes with the drill aimed from the dorsal aspect of the ulna on either side of the crista into the bed of the fractured coronoid, close to the articular surface. The drill holes should be as wide apart as possible yet still be within the fracture bed.

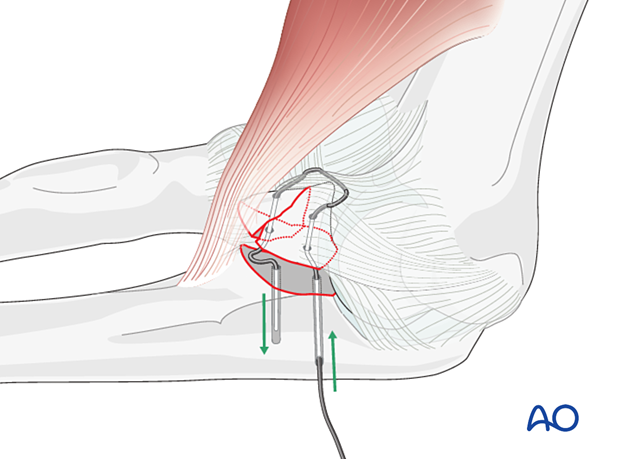

Reduction and fixation

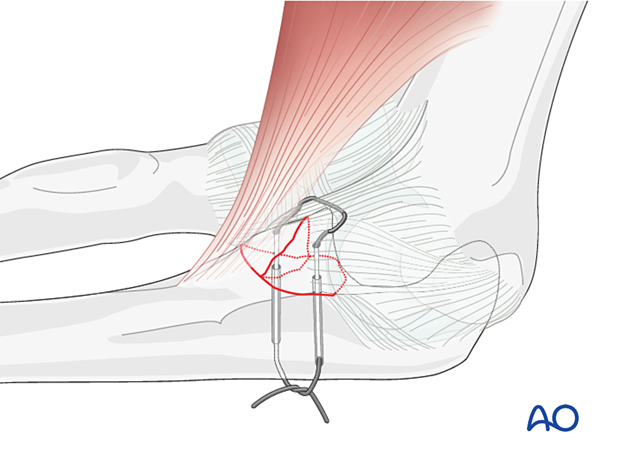

With a suture passer, pass one or two Nr. 2 or Nr. 5 nonabsorbable sutures through the holes and through the joint capsule.

Reduce the fragments as well as possible and tie the sutures with the elbow in flexion.

It is often difficult to obtain a perfect articular reduction but minor malreduction can be tolerated if the joint is stable.

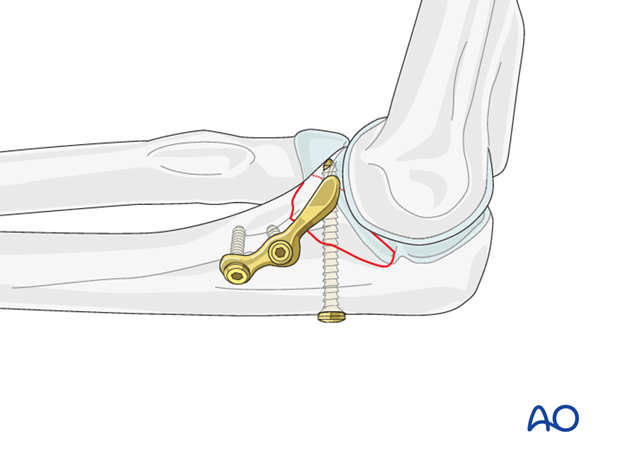

6. Fixation with anterior buttress plate

Plate selection

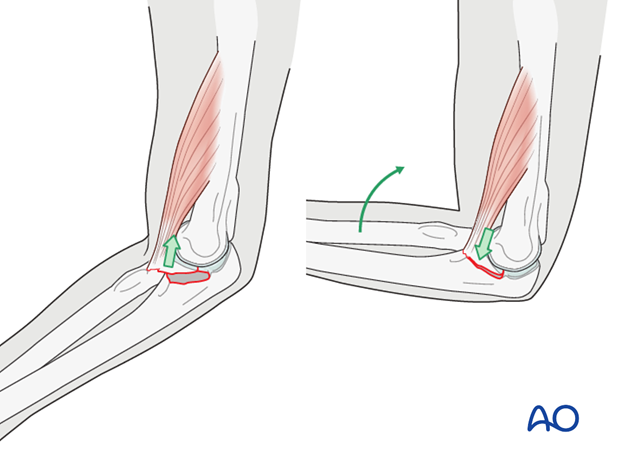

The forces acting on a larger fractured coronoid fragment of type I and II are proximal distraction by the brachialis and a distally directed shearing force created by the humerus pushing forward. An anterior plate counteracts the shearing force (buttress effect), increasing stability and permitting early motion.

For larger anteromedial facet coronoid fractures (Mayo type II), the following can be used:

- Precontoured anatomic plate with or without additional lag screws

- Properly contoured three-hole one-third tubular plate

- T-plate

Selection of approach

A single midline posterior approach provides access to nearly the entire elbow. Alternatively, a medial approach can be used.

This decision depends on associated elbow fracture components that need treatment. For example, most fractures of the anteromedial facet have an associated LCL injury that needs repair. A midline posterior approach with elevation of medial and lateral flaps might be better in these cases.

Identify the ulnar nerve.

Decompress the ulnar nerve where it enters the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU).

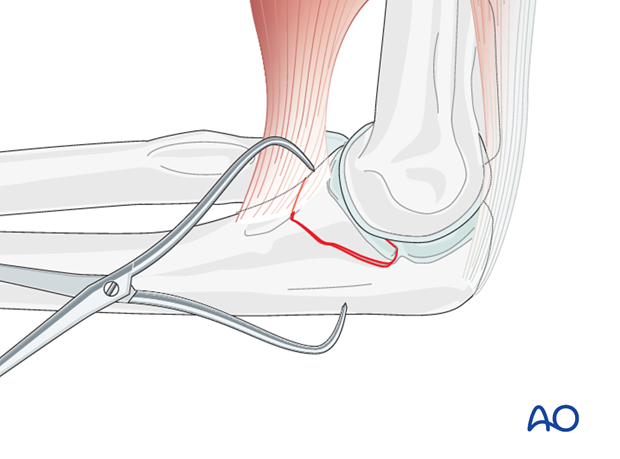

The anteromedial facet is best approached via the natural split in the FCU, between the two heads of this muscle.

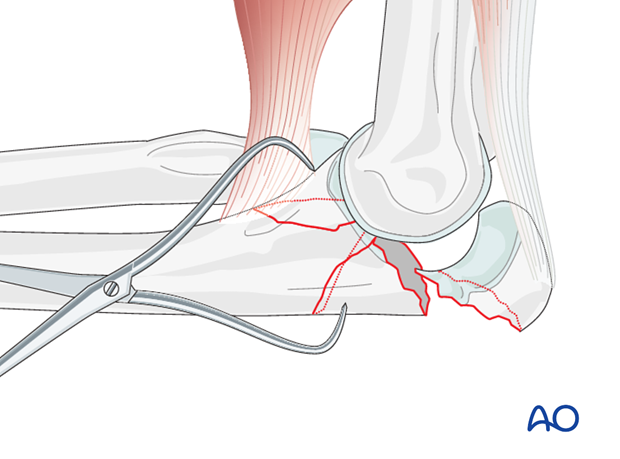

Reduction

Flex the elbow to relax the brachialis and thereby facilitate coronoid reduction.

Reduce the coronoid and fix it temporarily with a pointed reduction clamp and/or a K-wire.

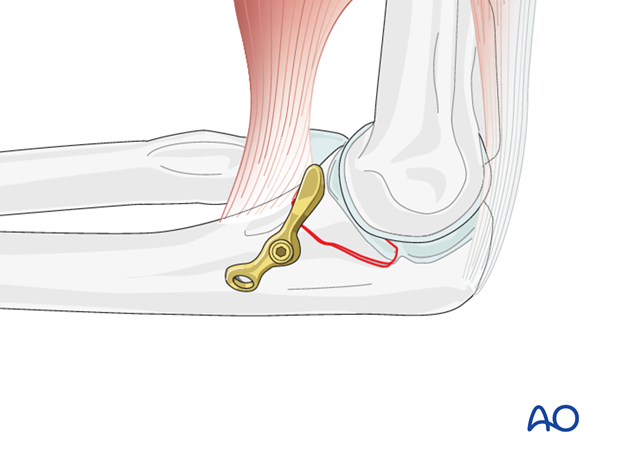

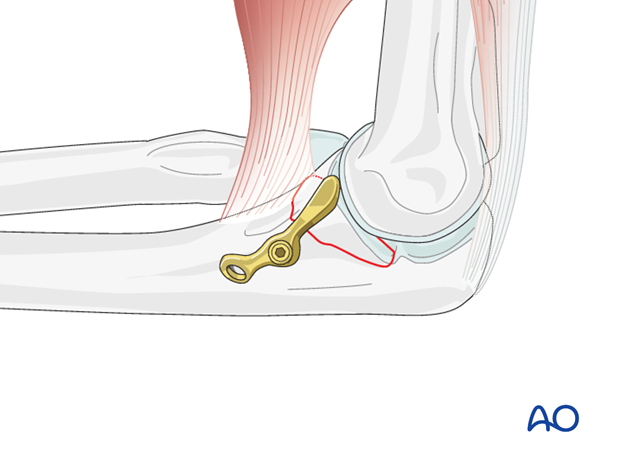

Apply the buttress plate by inserting the proximal screw but not fully tightened.

Rotate the plate so that it compresses against the anteromedial facet fragment.

Place then a second screw more distally to increase the stability of fixation, but not fully tightened.

Fracture compression is achieved, and fixation is completed by first fully tightening the proximal, then the distal screw.

Even if there is no screw in the fragment itself, the buttressing effect of the plate will prevent loss of fixation when the capsule pulls on the fragment in extension.

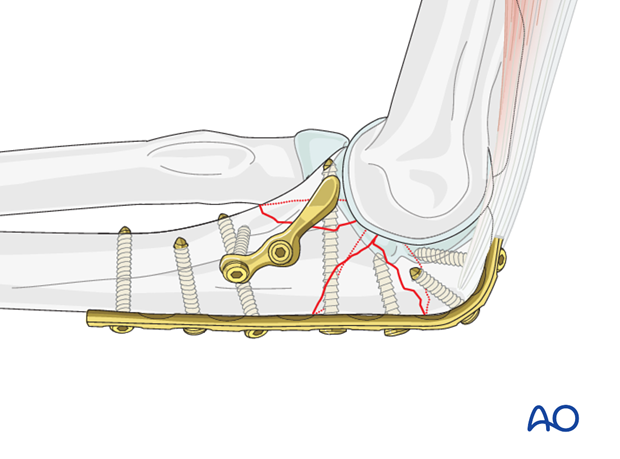

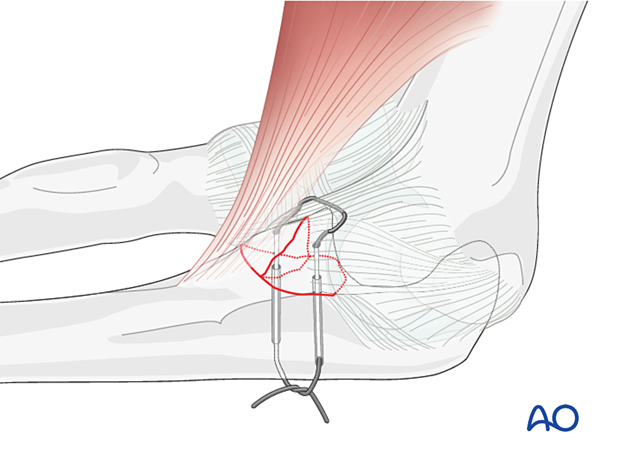

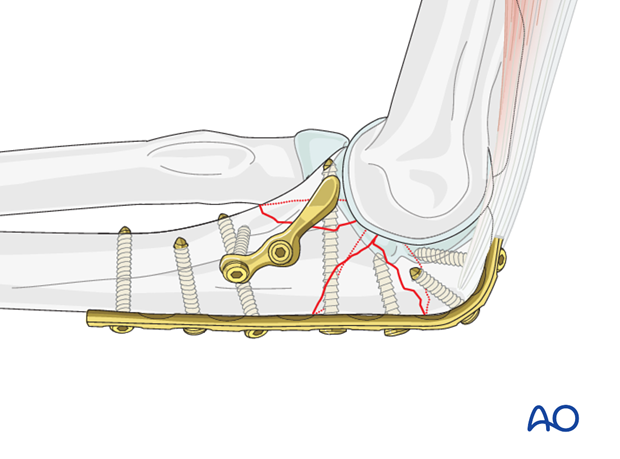

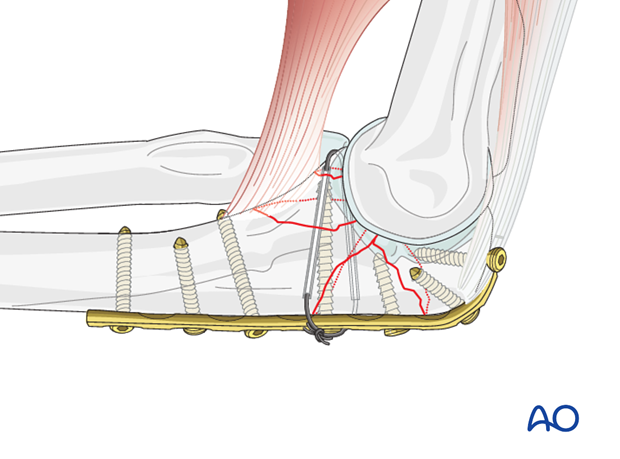

7. Lag screw fixation with posterior plate

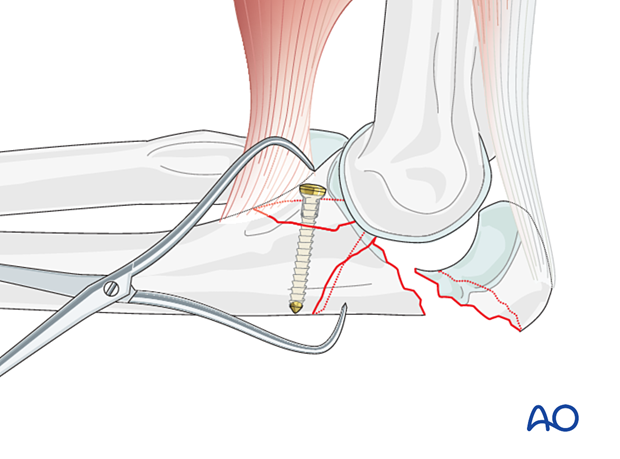

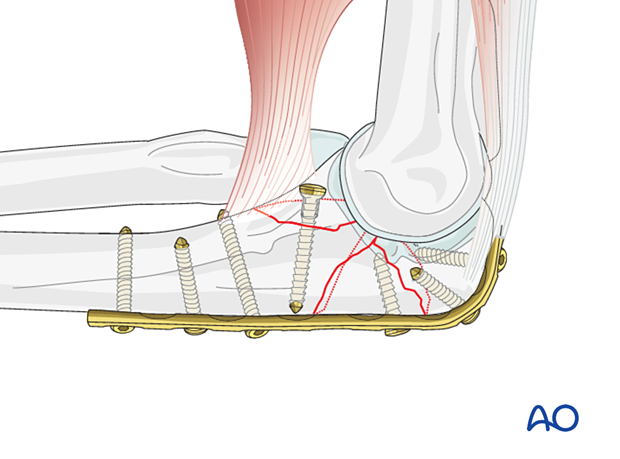

In basilar coronoid fractures, usually associated with olecranon fracture dislocations (shown here), a single large fragment might be fixable with one or more small lag screws inserted in a posteroanterior direction. These may be through, or separate, from a posterior plate.

Reduction

Open the fracture by reflecting the olecranon proximally.

Flex the elbow to relax the brachialis and thereby facilitate coronoid reduction.

Reduce the coronoid and fix it temporarily with a pointed reduction clamp and/or a K-wire.

Fixation of large coronoid fragment and olecranon

Coronoid fixation with independent K-wire or lag screwIf it is not planned to fix the coronoid fracture with a lag screw through a plate, the coronoid is now fixed with either a threaded K-wire or a small lag screw inserted outside of the planned plate position.

Reduce the olecranon fracture and fix it with a plate.

Alternatively, reduce and stabilize the olecranon fracture with a plate.

Then fix the coronoid with a small lag screw through the plate.

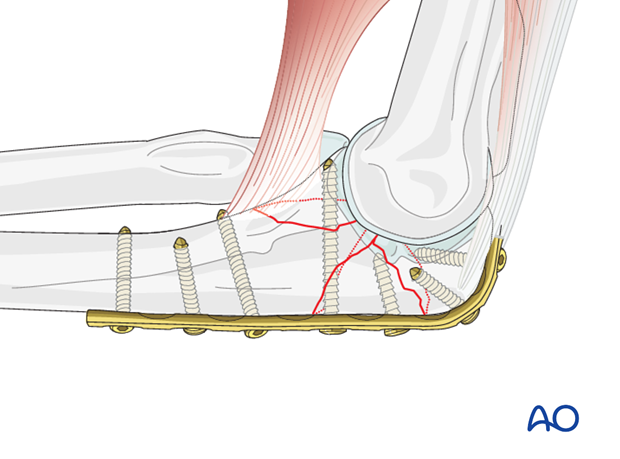

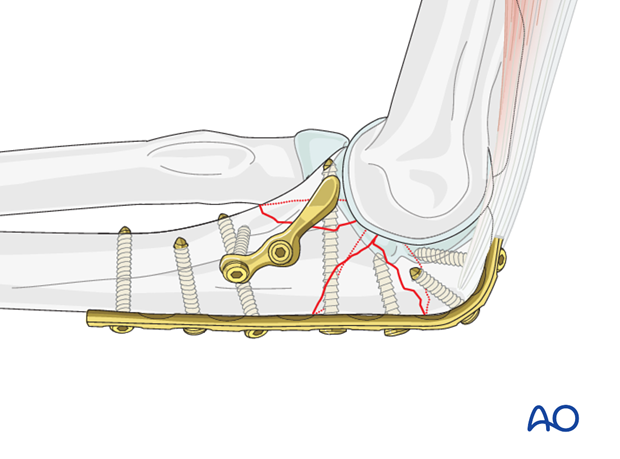

Fixation of comminuted or unstable coronoid

Comminution or instability may be addressed by adding an anterior plate over the front of the coronoid process (buttress effect) to increase the stability and allow early motion. This can be performed with a contoured three-hole one-third tubular plate or a custom plate as described above.

Medial and/or lateral fragments can be buttressed onto the distal shaft with small plates (2.0/2.4/2.7) to augment stability and help with alignment and reduction.

Occasionally, a small, comminuted fragment may require suture fixation as described above. In this case, the suture is tied after the plate has been fixed.

8. Postoperative treatment following ORIF

Postoperatively, the elbow may be placed for a few days in a posterior splint for pain relief and to allow early soft tissue healing, but this is not essential. To help avoid a flexion contracture, some surgeons prefer to splint the elbow in extension.

If drains are used, they are removed after 12–24 hours.

Mobilization

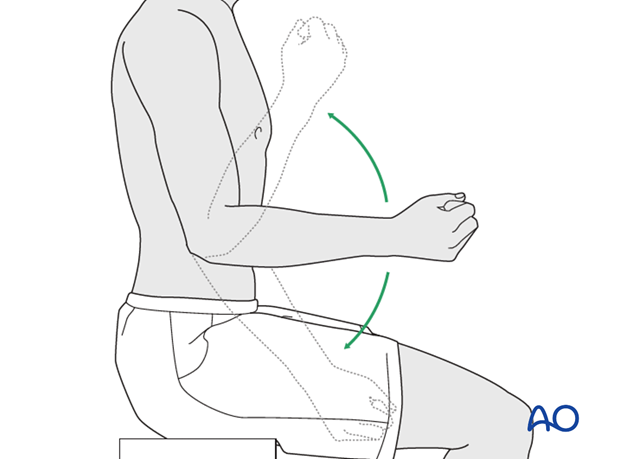

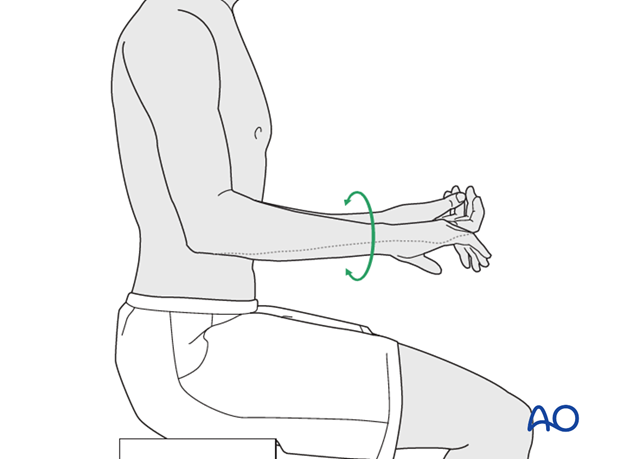

Active assisted motion is encouraged within the first few days including gravity-assisted elbow flexion and extension. Encourage the patient to move the elbow actively in flexion, extension, pronation and supination as soon as possible. Delay exercises against resistance until healing is secure.

Use of the elbow for low intensity activities is encouraged, but should not be painful.

Range of motion must be monitored to prevent soft tissue contracture.

Prevent loading of the elbow for 6–8 weeks.

Monitor the patient to assess and encourage range of motion, and return of strength, endurance, and function, once healing is secure.

Follow up

The patient is seen at regular intervals (every 10–20 days at first) until the fracture has healed and rehabilitation is complete.

Implant removal

As the proximal ulna is subcutaneous, bulky plates and other hardware may cause discomfort and irritation. If so, they may be removed once the bone is well healed, 12–18 months after surgery, but this is not essential.