Salvage techniques

1. Principles

Introduction

There exist circumstances in which the patellar fragments cannot be reduced adequately and when function of the extensor apparatus remains compromised. Salvage procedures can produce surprisingly acceptable results. The secret is attention to operative detail by a skilled surgeon.

Patellar salvage

There are various techniques for patellar salvage:

- Partial patellectomy

- Total patellectomy

- Patellar reconstruction for central articular impaction injuries

- Repair of sleeve fractures of the patella (a detailed description of this technique is available in the dedicated section)

Partial patellectomy is preferred to total patellectomy, whenever possible, as it maintains the extensor lever arm.

If patellar salvage fails, patellofemoral osteoarthritis may well occur. Late salvage after patellar fractures may ultimately require a specialist knee arthroplasty, such as some form of semi-constrained knee prosthesis.

2. Patient preparation and approach

Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position with the knee flexed 30°.

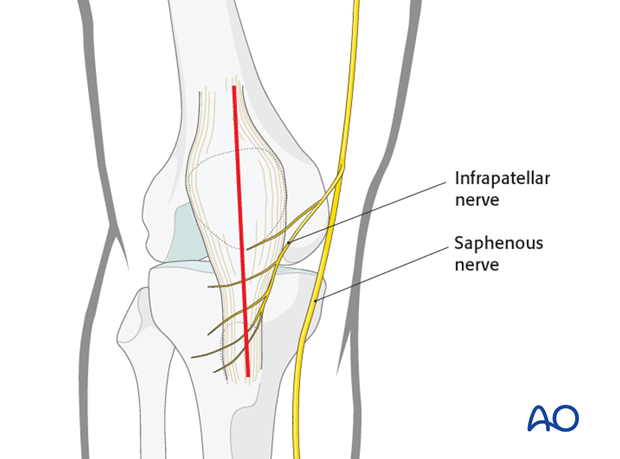

Approach

For this procedure a mid-axial longitudinal approach is used.

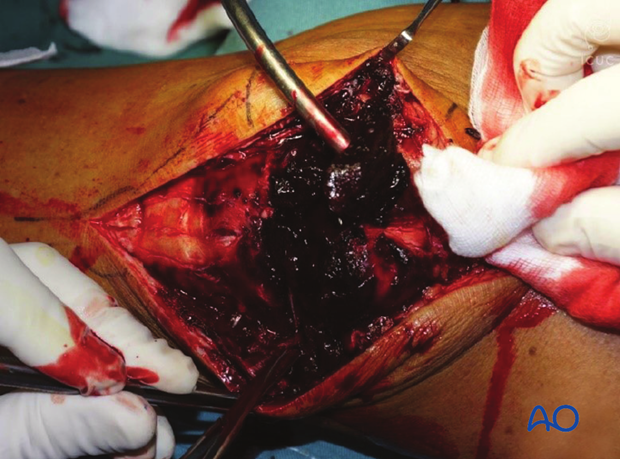

3. Debridement

The knee joint and fracture lines must be irrigated and cleared of blood clots and small debris to allow exact reconstruction.

If the comminuted area is significant, the bone fragments should be removed to prevent osteophyte formation.

Large patellar fragments can usually be reconstructed to try to save as much patella as possible.

If the articular surface is badly injured, it should still be salvaged as the patient may get many years from this reconstruction before another procedure need be done.

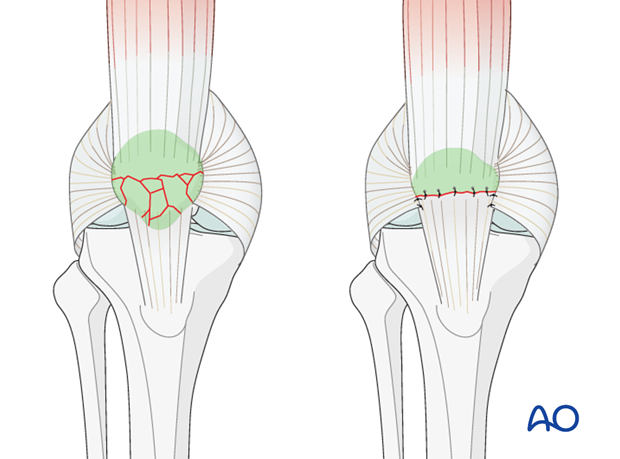

4. Partial patellectomy

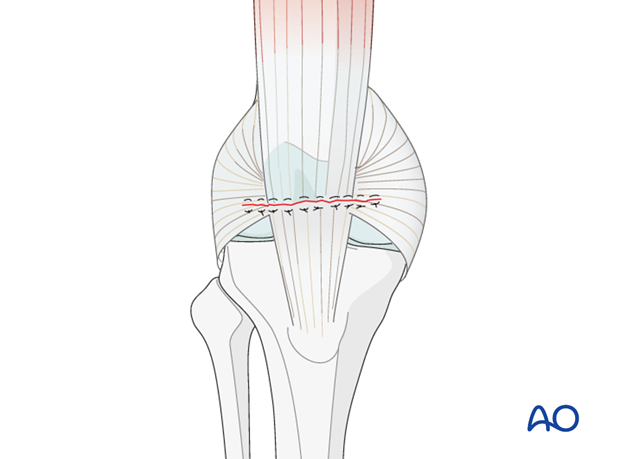

A comminuted upper or lower pole is best managed by taking out all small bone fragments.

It is most often the distal pole of the patella that is fractured.

Suture the most proximal part of the remaining patellar tendon to the remaining patella, using transosseous sutures, or suture anchors. To avoid tilting the patellar fragment and increasing patellofemoral contact forces, the patellar tendon should be attached near the posterior aspect of the remaining patellar fragment.

Then repair the lateral and medial parapatellar retinacula.

The biomechanics of the remaining patellofemoral joint will be abnormal but will give a better clinical outcome than a total patellectomy.

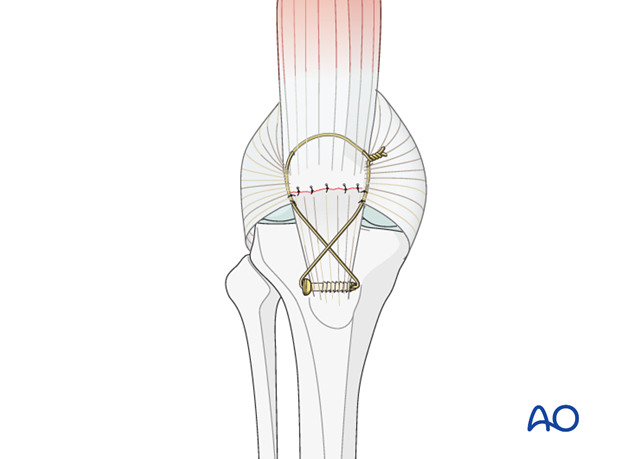

The addition of a patellotibial cerclage wire should be used to protect the sutures.

5. Total patellectomy

Total patellectomy is reserved for severe multifragmentary fractures of the patella, which may be combined with significant osteochondral damage to the patellofemoral joint. In situations where repair is not possible, the entire patella is excised.

Remove the entire patella by sharp dissection, as close to the bone as possible.

Suture the proximal extensor mechanism, with a nonabsorbable suture, to the distal extensor mechanism.

The lateral and medial patellar retinacula – if torn – should also be repaired.

After total patellectomy early functional results are surprisingly good, but deteriorate with time.

Pearl: When “shelling out” the bony portions of the patella from the extensor mechanism, use a series of new, sharp scalpel blades (they blunt quickly) and cut into the “axilla” of the fiber attachments to the bone. This keeps the dissections as close to the bone as possible, ensuring maximal preservation of the extensor tendinous tissue. This is especially important over the front of the patella.

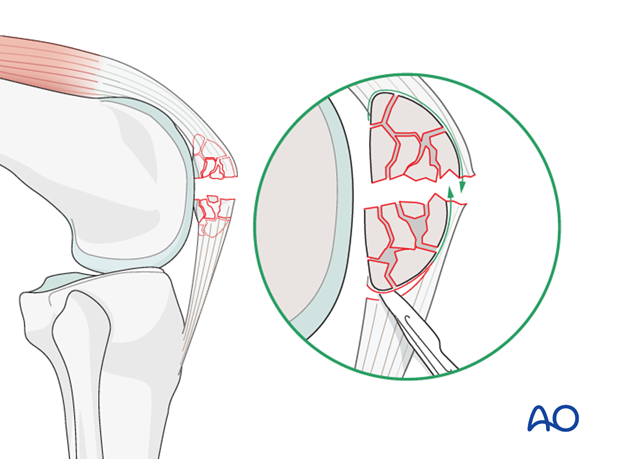

6. Patellar reconstruction for central articular impaction injuries

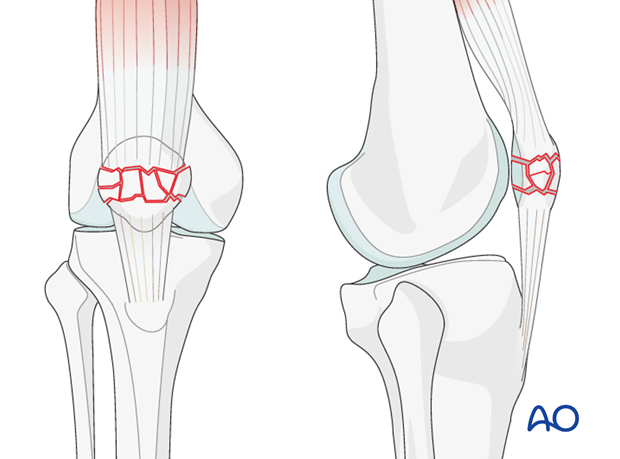

Severe central comminution of the patella is a rare, but very difficult injury to treat.

As a salvage procedure, the injured segment may be removed by transverse osteotomy.

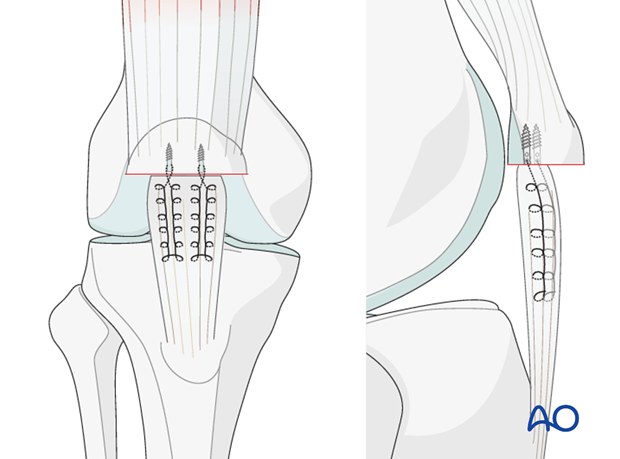

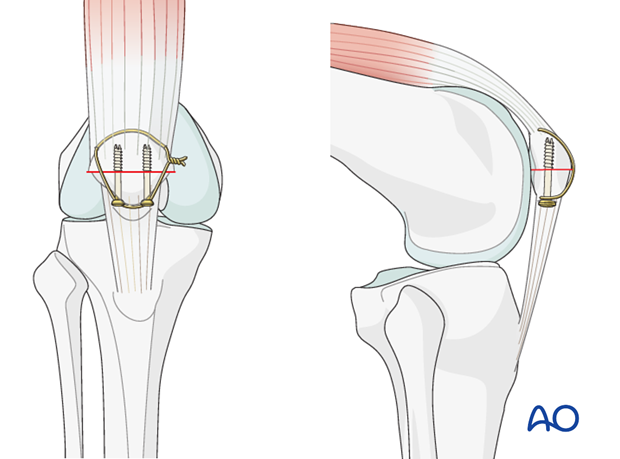

The osteotomy may be secured with two 3.5 mm partially threaded, cortical, cannulated screws inserted as lag screws.

Ensure that there is maximally possible alignment of the articular surfaces of the residual 2 portions of the patella: this may result in an anterior step at the osteotomy, which is of no consequence.

This patellar construct may well require augmentation of the fixation with cerclage compression wiring.

7. X-ray control

The final result is checked in the AP and lateral planes using an image intensifier or X-ray.

8. Aftercare following patellar salvage techniques

Introduction

Active knee function requires an intact knee extensor mechanism, a mobile patella, a well-preserved patello-femoral joint and muscle strength.

Knee stiffness and muscle weakness can become a problem after the necessary period of casting. Once deemed to be healed, a regimen of progressive knee mobilization and muscle strengthening must be supervised closely by the rehabilitation team.

Functional treatment

Patellar salvage may not give stable fixation. A full extension knee splint should be used at all times. Early active mobilization should only be started with caution, as judged appropriate by the surgeon. Usually the anterior incision is slow to heal as it is over a flexion surface and so it is usually best to leave the knee in extension for at least a week. Static isometric quadriceps exercises should be started on postoperative day 1 with the splint in place. At a later stage, special emphasis should be placed on active knee and hip movement.

Total patellectomy

It is essential to place the knee in a complete extension knee splint for 6 weeks after this procedure.

Weight bearing

Weight bearing may be complete with the knee extension splint in place.

If the fixation is stable, a removable knee splint is worn until quadriceps control is regained. Full weight bearing may be performed, with the aid of crutches, or a walker, from postoperative day 1, if the fixation is judged to be sufficiently stable. It is better to stay on the side of caution. Some knee stiffness is preferable to a failed salvage procedure.

Follow-up

Wound healing should be assessed regularly within the first two weeks. X-rays should be taken at 6 and 12 weeks (except after total patellectomy). A longer period may be required if the fracture healing is delayed.

Implant removal

Implant removal may be required, as a cerclage wire may be prominent under the skin. Implant removal should not be undertaken until a minimum of 3 months and may be delayed up to one year postoperatively. Patients should be warned that patellotibial cerclage wires may break during the healing process and may need to be removed earlier.

Thrombo-embolic prophylaxis

Consideration should be given to thrombo-embolic prophylaxis, according to local treatment guidelines.