Lag-screw fixation

1. General considerations

Long oblique/spiral fracture

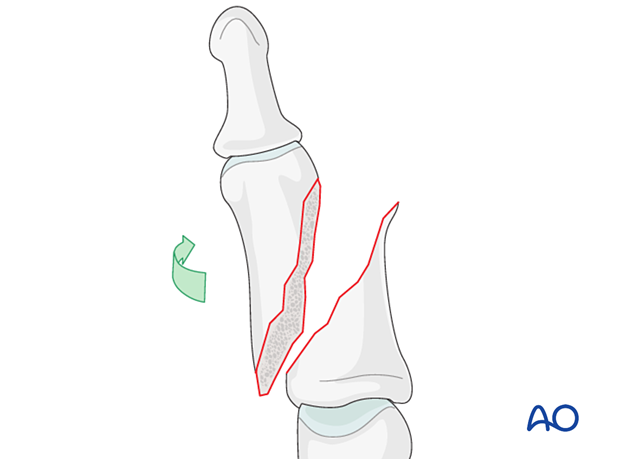

Treatment of long oblique and spiral fractures is similar. The difference is in the screw insertion in relation to the fracture plane, which is strictly single in the long oblique fractures. In the spiral fractures, the fracture plane is helical and, therefore, each screw is inserted in a slightly different direction.

Indirect reduction is achieved by traction and digital manipulation. Usually, these fractures are unstable.

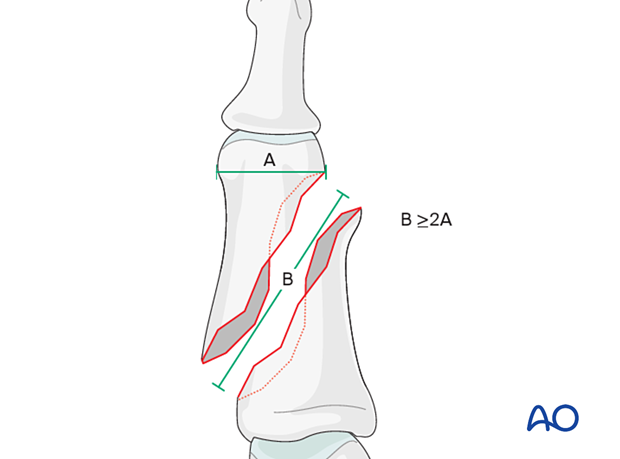

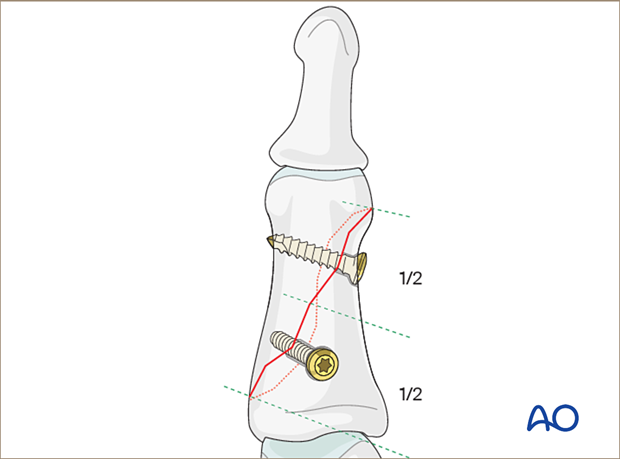

In a long fracture, fixation with two, or more, lag screws is usually sufficient, and no protection plate is necessary.

A good rule is the following: The fracture line (B) should be at least twice the length of the diameter of the phalangeal diaphysis (A), ie, B ≥ 2A for interfragmentary lag screws to provide sufficient fixation and stability.

Percutaneous vs open reduction and fixation

For spiral fractures, percutaneous treatment is not an option.

Percutaneous reduction and fixation may be performed with acute oblique fractures.

The advantage of a percutaneous reduction and fixation is:

- Shorter operation time

- Less soft-tissue damage

- Faster mobilization

This treatment option needs some skills and experience and special reduction forceps to avoid impingement of swollen soft tissue (atraumatic technique).

If a percutaneous reduction is not achievable, the treatment can be changed to an open surgery.

Open reduction and fixation may be used in acute and delayed cases. Addition of a neutralization plate also requires an open surgery.

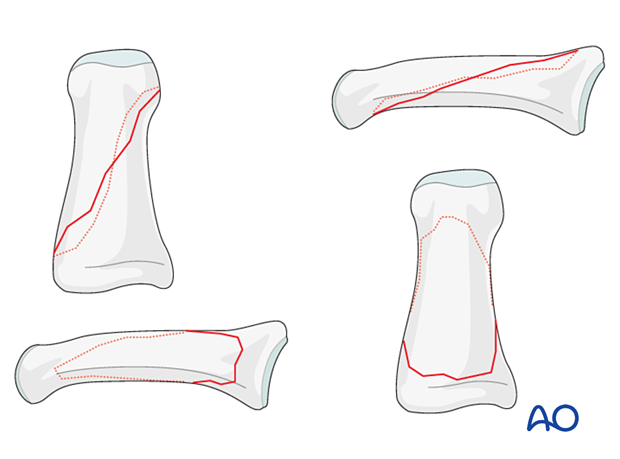

Fracture plane

Obliquity of the fracture is possible either in the plane visible in the AP view or the lateral view. Always confirm the fracture configuration with views in both planes.

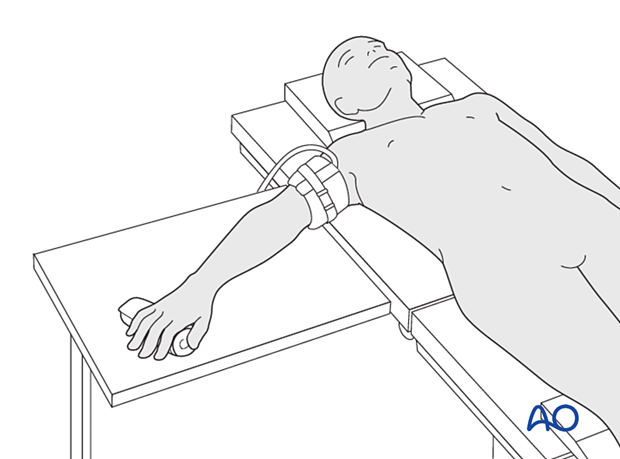

2. Patient preparation

Place the patient supine with the arm on a radiolucent hand table.

3. Approaches

If the fracture is visible on AP view a lateral approach is used.

If the fracture is visible on lateral view a dorsal approach is used.

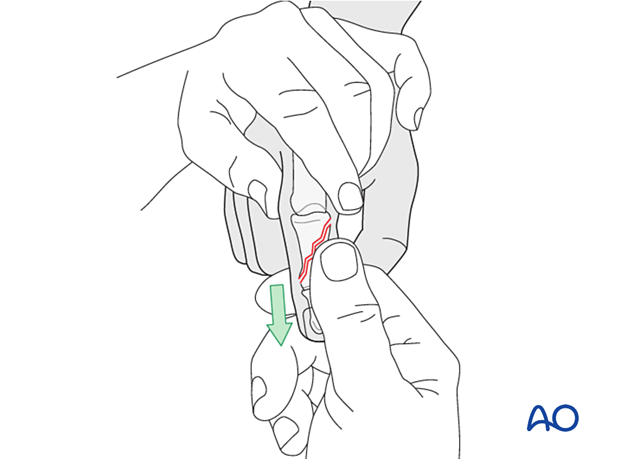

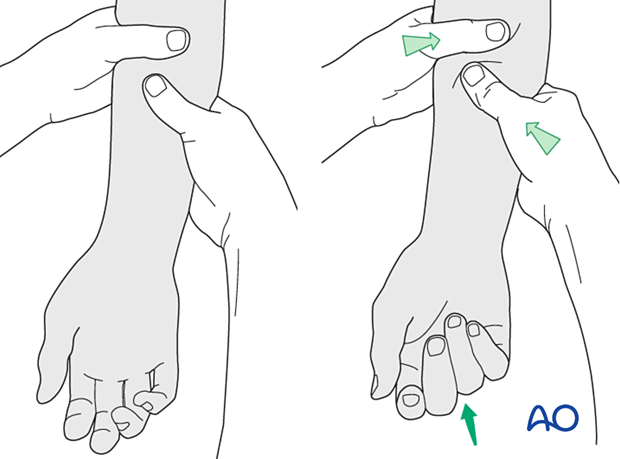

4. Closed reduction

Reduction can be achieved by traction and flexion exerted by the surgeon.

Confirm reduction with an image intensifier.

Hold the reduction with reduction forceps designed for percutaneous technique. Impingement of soft tissues should be avoided.

5. Open reduction

If closed reduction is not successful or in a nonacute case, proceed with an open reduction.

When indirect reduction is not possible, this is usually due to interposition of parts of the extensor apparatus.

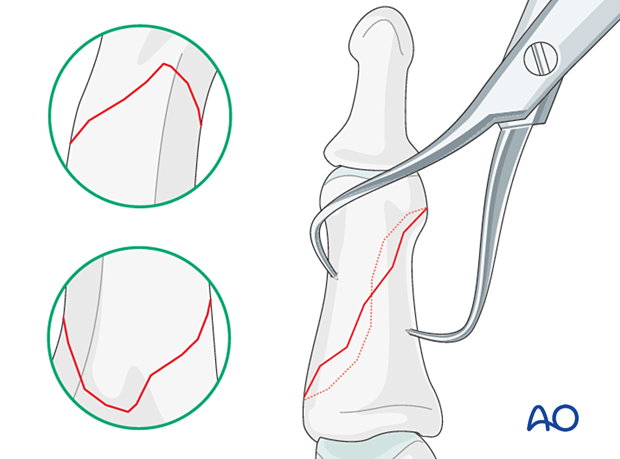

Fracture visualization

Rotate the finger, open the fracture, and irrigate the fracture zone for good direct visualization.

Determine the exact geometry of the fracture. This is very important for later screw placement.

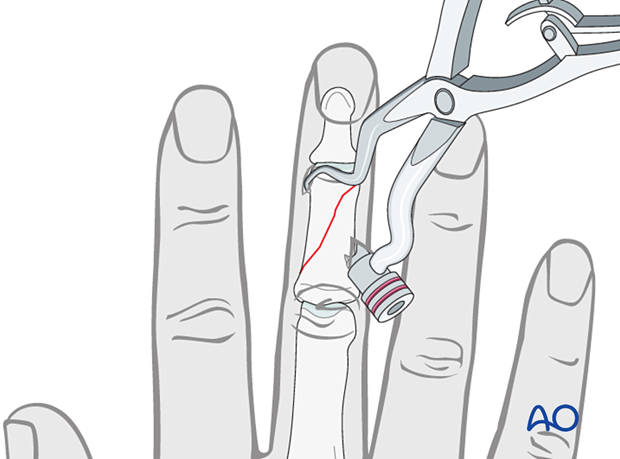

Direct reduction

Gently use pointed reduction forceps to reduce the fracture anatomically.

Confirm reduction under image intensification.

It is mandatory to confirm that the apex of each fracture fragment has been properly reduced; otherwise, malrotation may result.

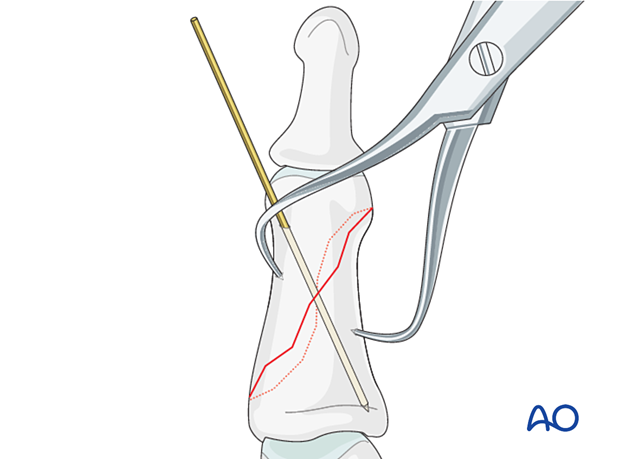

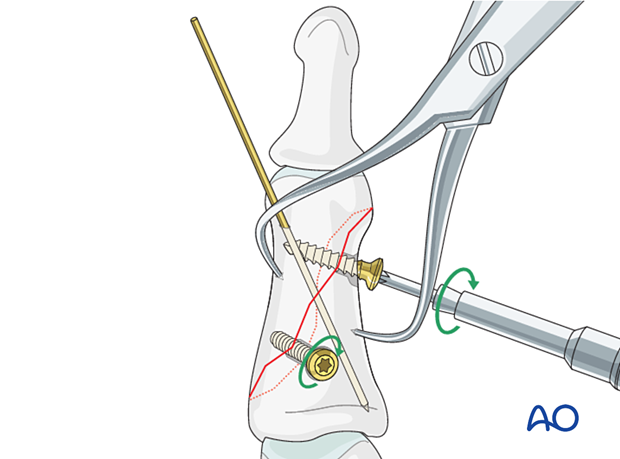

Preliminary fixation

Provisionally hold the reduction with either two K-wires, or one K-wire and a reduction forceps. Avoid the planned screw trajectories.

6. Checking alignment

Identifying malrotation

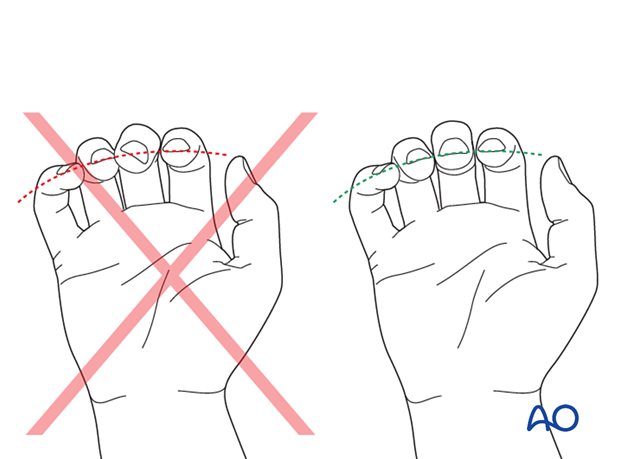

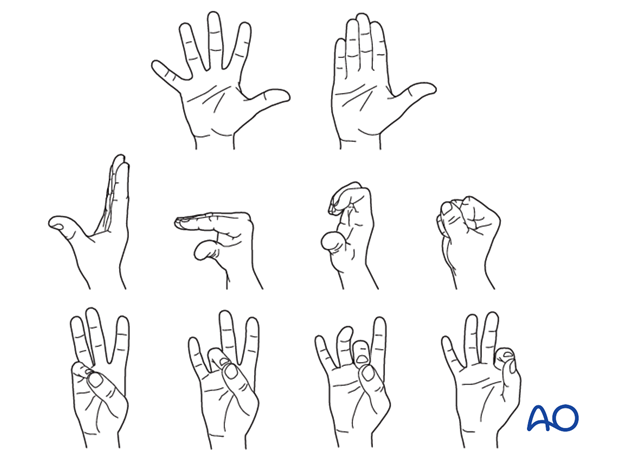

At this stage, it is advisable to check the alignment and rotational correction by moving the finger through a range of motion.

Rotational alignment can only be judged with the fingers in a degree of flexion, and never in full extension. Malrotation may manifest itself by overlap of the flexed finger over its neighbor. Subtle rotational malalignments can often be judged by tilting of the leading edge of the fingernail when the fingers are viewed end-on.

If the patient is conscious and the regional anesthesia still allows active movement, the patient can be asked to extend and flex the finger.

Any malrotation is corrected by direct manipulation and later fixed.

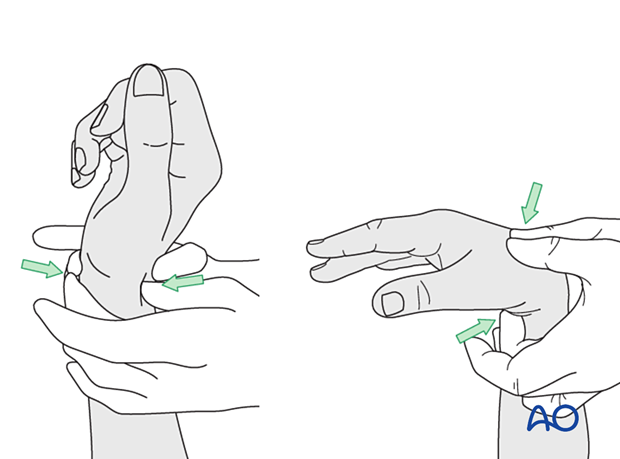

Using the tenodesis effect when under anesthesia

Under general anesthesia, the tenodesis effect is used, with the surgeon fully flexing the wrist to produce extension of the fingers and fully extending the wrist to cause flexion of the fingers.

Alternatively, the surgeon can exert pressure against the muscle bellies of the proximal forearm to cause passive flexion of the fingers.

7. Planning for screw insertion

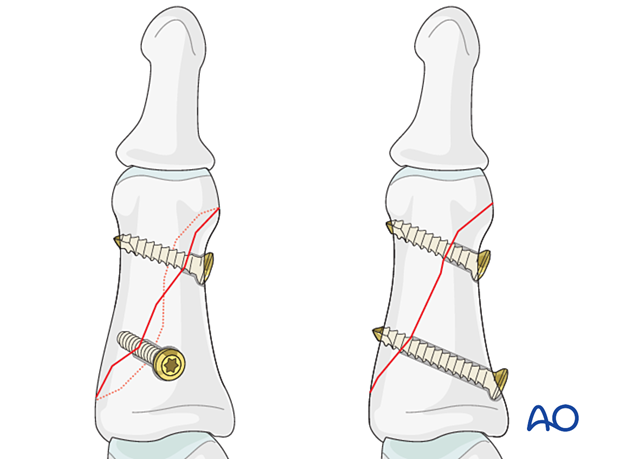

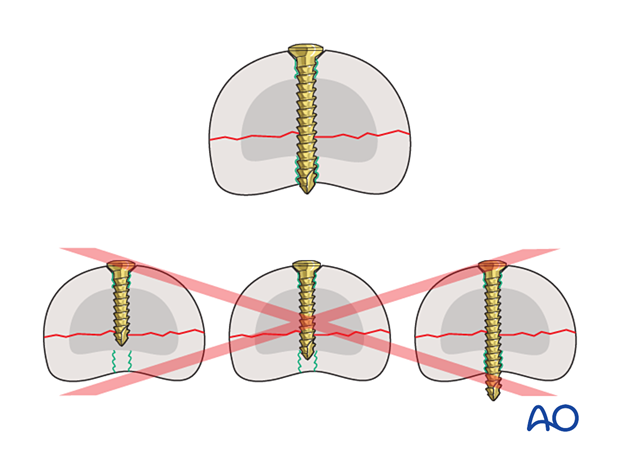

Two screws should be inserted, equally spaced.

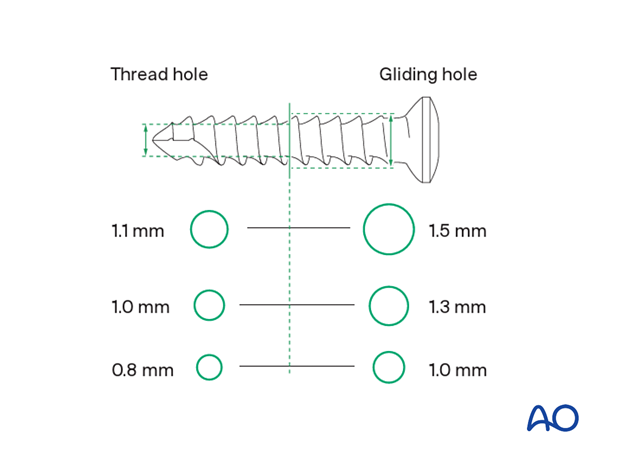

Screw size

The exact size of the diameter of the screws used will be determined by the fragment size and the fracture configuration.

The various gliding and thread hole drill sizes for different screws are illustrated here.

8. Screw fixation principles

Insert both screws before fully tightening them.

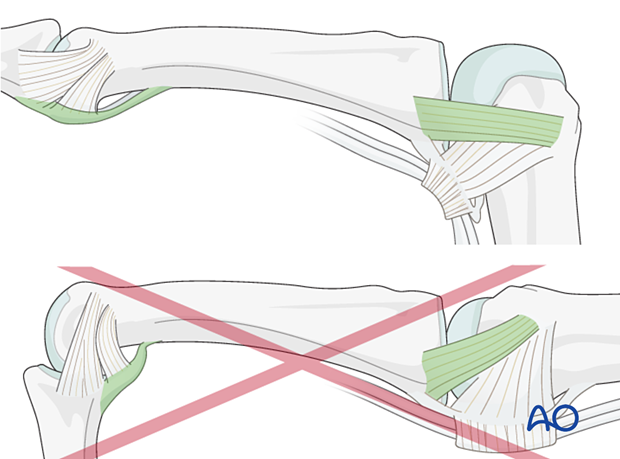

Insert them as perpendicular as possible to the fracture plane. In spiral fractures, the result is that the screws follow a helical disposition.

It is important to tighten the two screws alternately not to displace the fragment.

Countersinking in the diaphysis should be performed with care as it risks iatrogenic fractures.

Tendon ruptures around the PIP joint need to be reconstructed with bone tunneling or suture anchoring.

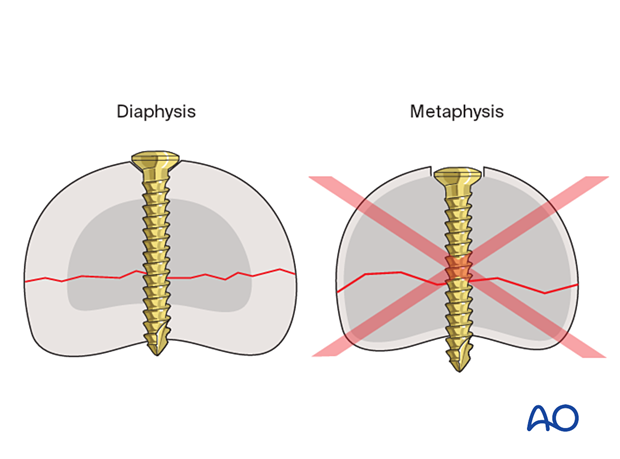

Pitfall: countersinking in the metaphysis

Screw length pitfalls

- Too short screws do not have enough threads to engage the cortex properly. This problem increases when self-tapping screws are used due to the geometry of their tip.

- Too long screws endanger the soft tissues, especially tendons and neurovascular structures. With self-tapping screws, the cutting flutes are especially dangerous, and great care has to be taken that the flutes do not protrude beyond the cortical surface.

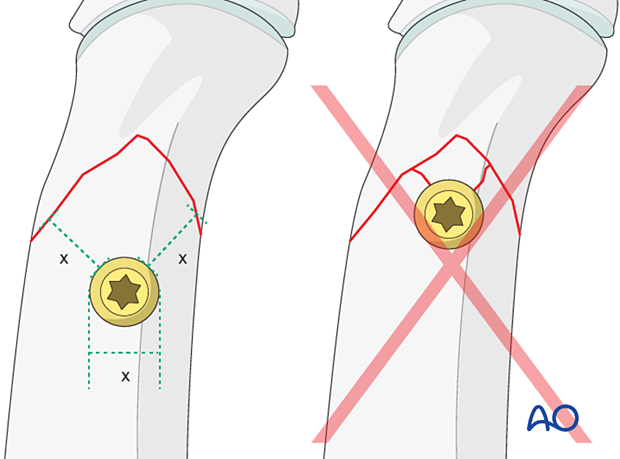

Pitfall: screw too close to the fracture

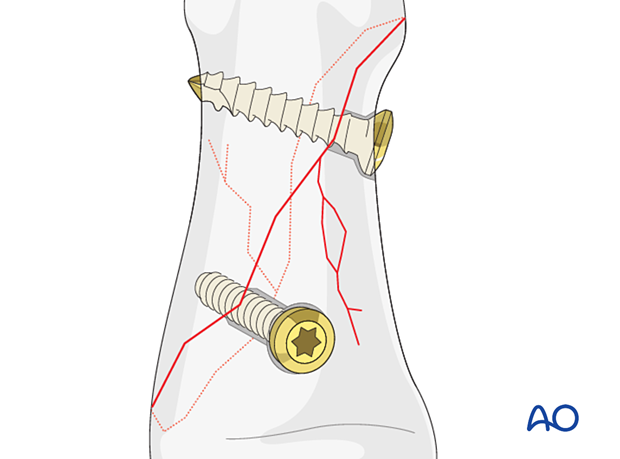

Pitfall: beware of fissure lines

9. Final assessment

Confirm reduction and fixation with an image intensifier.

10. Aftercare

Postoperative phases

The aftercare can be divided into four phases of healing:

- Inflammatory phase (week 1–3)

- Early repair phase (week 4–6)

- Late repair and early tissue remodeling phase (week 7–12)

- Remodeling and reintegration phase (week 13 onwards)

Full details on each phase can be found here.

Postoperative treatment

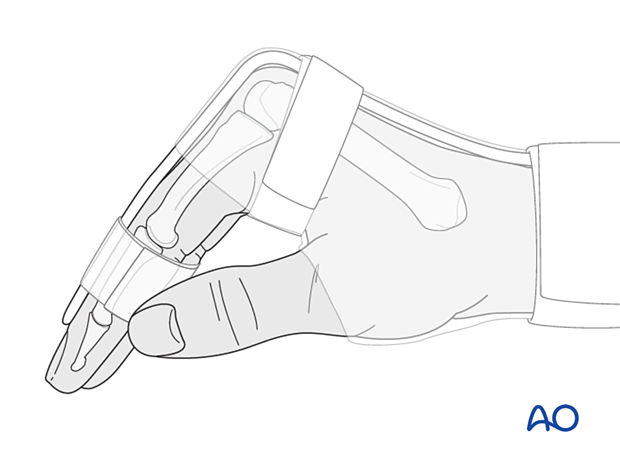

If there is swelling, the hand is supported with a dorsal splint for a week. This should allow for movement of the unaffected fingers and help with pain and edema control. The arm should be actively elevated to help reduce the swelling.

The hand should be immobilized in an intrinsic plus (Edinburgh) position:

- Neutral wrist position or up to 15° extension

- MCP joint in 90° flexion

- PIP joint in extension

The MCP joint is splinted in flexion to maintain its collateral ligaments at maximal length to avoid contractures.

The PIP joint is splinted in extension to maintain the length of the volar plate.

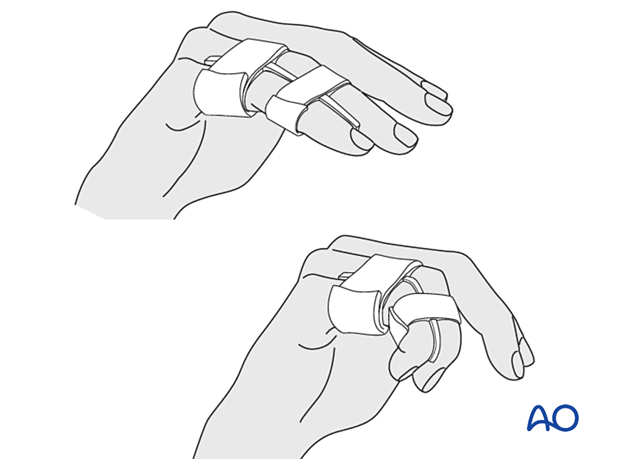

After swelling has subsided, the finger is protected with buddy strapping to neutralize lateral forces on the finger until full fracture consolidation.

Mobilization

To prevent joint stiffness, the patient should be instructed to begin active motion (flexion and extension) of all nonimmobilized joints immediately after surgery.

Follow-up

The patient is reviewed frequently to ensure progression of hand mobilization.

In the middle phalanx, the fracture line can be visible in the x-ray for up to 6 months. Clinical evaluation (level of pain) is the most important indicator of fracture healing and consolidation.

Implant removal

The implants may need to be removed in cases of soft-tissue irritation.

In case of joint stiffness or tendon adhesion restricting finger movement, arthrolysis or tenolysis may become necessary. In these circumstances, the implants can be removed at the same time.