Compartment syndrome in the arm

1. Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a true surgical emergency.

It is caused by increasing tissue pressure which prevents capillary blood flow leading to ischemia in muscle and nerve tissue.

If not treated, tissue necrosis with permanent loss of function may occur.

Compartment syndrome may occur as a result of:

- High-energy limb injuries

- Crushing injuries

- Reperfusion injury

- Burns

Compartment syndrome occurs in:

- Fascial compartments below the elbow

- Fascial compartments in the lower extremity, especially below the knee, but also in the thigh and gluteal regions

- Rarely, above the elbow

Treatment of compartment syndrome requires surgical release of the closed osteo-fascial compartments.

2. Definition

Compartment syndrome is characterized by a rise in pressure within a closed fascial compartment, sufficient to prevent effective capillary perfusion in muscle and nerve tissue.

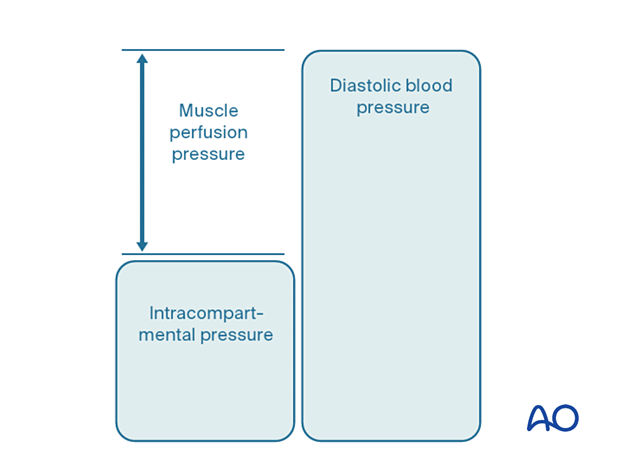

Normal tissue pressure is 0–10 mm Hg. The capillary filling pressure is essentially diastolic arterial pressure. When tissue pressure approaches the diastolic pressure, capillary blood flow ceases.

3. Diagnosis

Symptoms

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome is clinical, and requires:

- A high index of suspicion

- Appreciation of progressive symptoms which include worsening pain with increasing analgesia requirement, paresthesia, progressive loss of sensation, progressive loss of power

The diagnosis is difficult in patients with:

- Head injury

- Loss of consciousness for other reasons

- High spinal injury

- Regional nerve blockade

- Other distracting injuries

Signs

The signs of an evolving compartment syndrome include:

- Tenderness and swelling of the affected compartment

- Increase in pain with passive muscle stretching

- Increase in pain with active muscle contraction

- Later, sensory disturbance in the distribution of nerves traversing the compartment

- Later, weakness of muscles innervated by nerves traversing the compartment

4. Principles

General treatment principles

Effective management of an impending or established compartment syndrome requires:

- Recognition of the risk of, or actual compartment syndrome (symptoms and signs)

- Understanding the pathophysiology

- Recognition of the importance of immediate surgical treatment

- Intracompartmental pressure measurement in patients that cannot provide a reliable physical examination

- Resources to manage the aftercare and rehabilitation requirements

Pathophysiology

The most reliable measure of critical intracompartmental perfusion is the muscle perfusion pressure (MPP).

MPP is equal to the difference between diastolic blood pressure (dBP) and measured intramuscular pressure.

This difference in pressure reflects tissue perfusion more reliably than absolute intramuscular pressure.

When the muscle perfusion pressure is reduced to a level at which no capillary perfusion occurs, hypoxia leading to ischemia, and subsequent necrosis will occur.

The critical muscle perfusion pressure depends on the specific anatomical compartment affected.

Intracompartmental pressure measurement

When the clinical symptoms and signs of compartment syndrome are present, there is no benefit in measuring intracompartmental pressures, and an immediate fasciotomy should be performed.

When it is difficult to confirm the diagnosis, intracompartmental pressure measurement is helpful:

- To confirm the diagnosis

- To monitor a compartment at risk of increasing pressures

- To avoid unnecessary fasciotomy

- To measure intracompartmental pressures after decompression if symptoms persist

There are several techniques for the measurement of intracompartmental tissue pressure:

- Commercially available intracompartmental pressure device

- Large-bore needle and manometer

- Electronic strain gauge

If the necessary equipment is not available for direct intracompartmental pressure measurement, then the diagnosis must be assumed if there is reasonable clinical suspicion, and immediate fasciotomies must be performed.

Timing

Reversible ischemiaIn established muscle compartment syndrome, nerve and muscle tissue will become ischemic within less than two hours.

It is therefore of paramount importance that the intracompartmental pressure be released as an emergency intervention.

Arterial injury proximal to the compartment can also cause intracompartmental tissue ischemia without the associated early rise in intracompartmental pressure. After restoration of arterial flow, the subsequent capillary leakage may cause intracompartmental pressure to rise, leading to further ischemia. This is known as reperfusion injury.

It is generally accepted that after 6–8 hours of inadequate muscle perfusion pressure (MPP), extensive muscle necrosis is inevitable. Release of the muscle compartments involved will not prevent severe muscle contracture.

Fasciotomy of compartments within which muscle necrosis has already happened has a high risk of infection.

Amputation may be required.

Ischemic muscles eventually become atrophic and contracted. The movement of joints proximal and distal to the affected muscular compartment will be limited. The limb distal to the affected compartment may be insensate. The function of the limb is inevitably insufficient. This is known as “Volkmann’s ischemic contracture”.

5. Compartmental anatomy

Proximal forearm

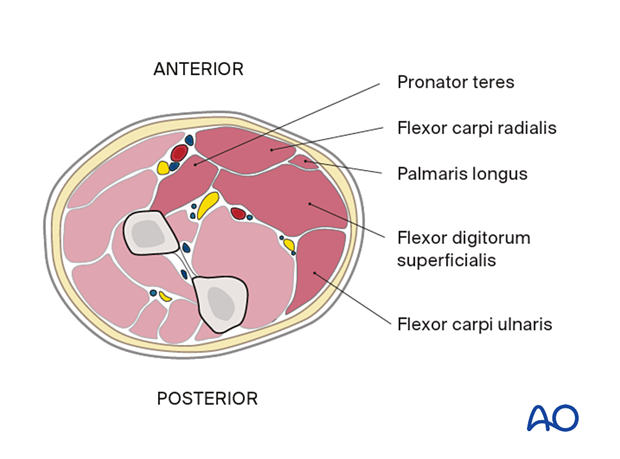

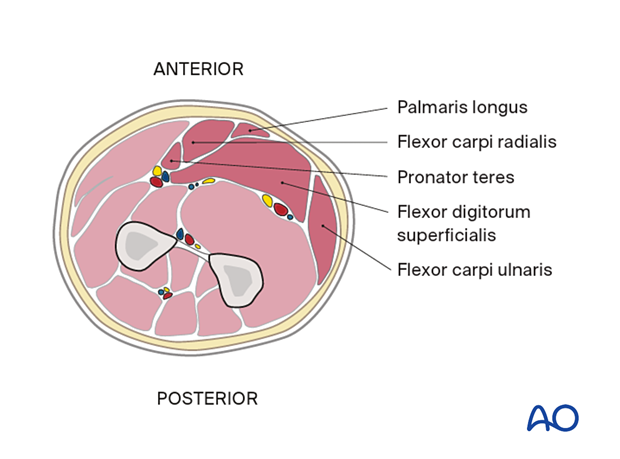

Superficial flexor compartmentThe muscles of the superficial flexor compartment in the proximal forearm comprise the following:

- Pronator teres

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor digitorum superficialis

- Flexor carpi ulnaris

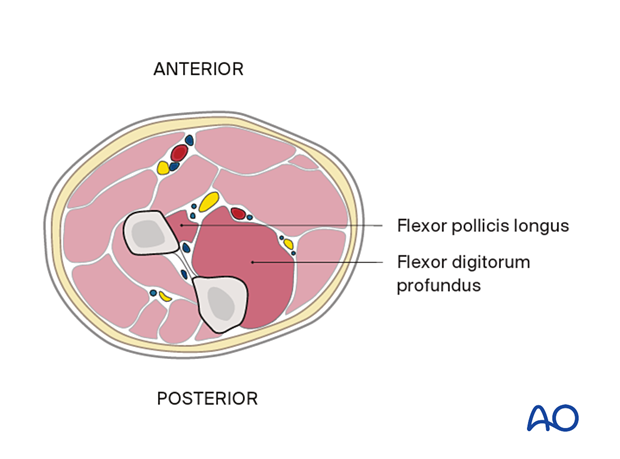

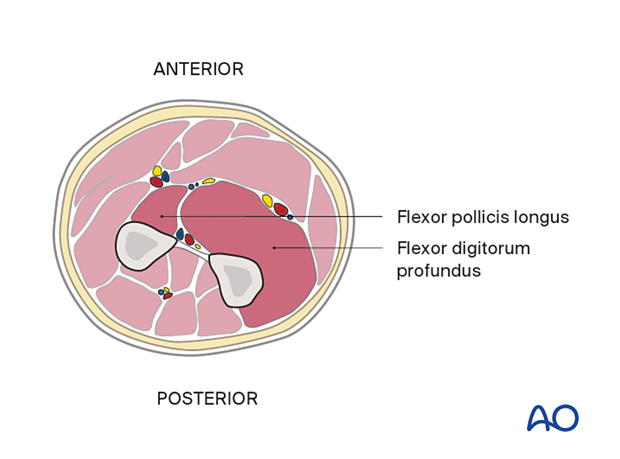

The muscles of the deep flexor compartment in the proximal forearm comprise the following:

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Flexor digitorum profundus

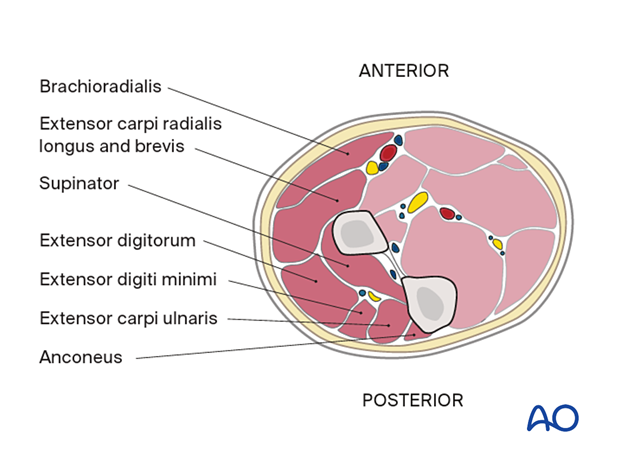

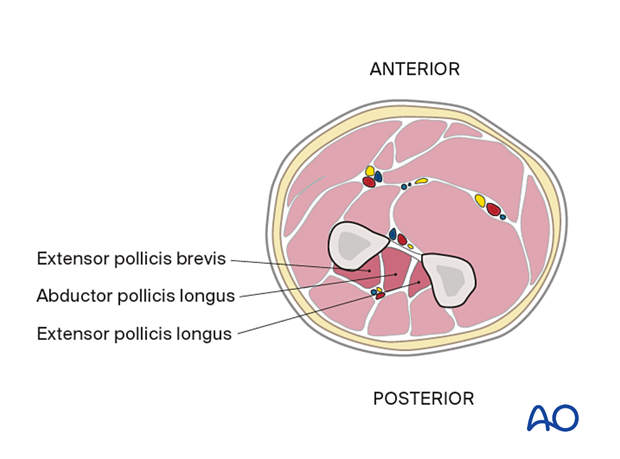

The muscles of the extensor compartment in the proximal forearm comprise the following:

- Brachioradialis

- Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis

- Supinator

- Extensor digitorum

- Extensor digiti minimi

- Extensor carpi ulnaris

- Anconeus

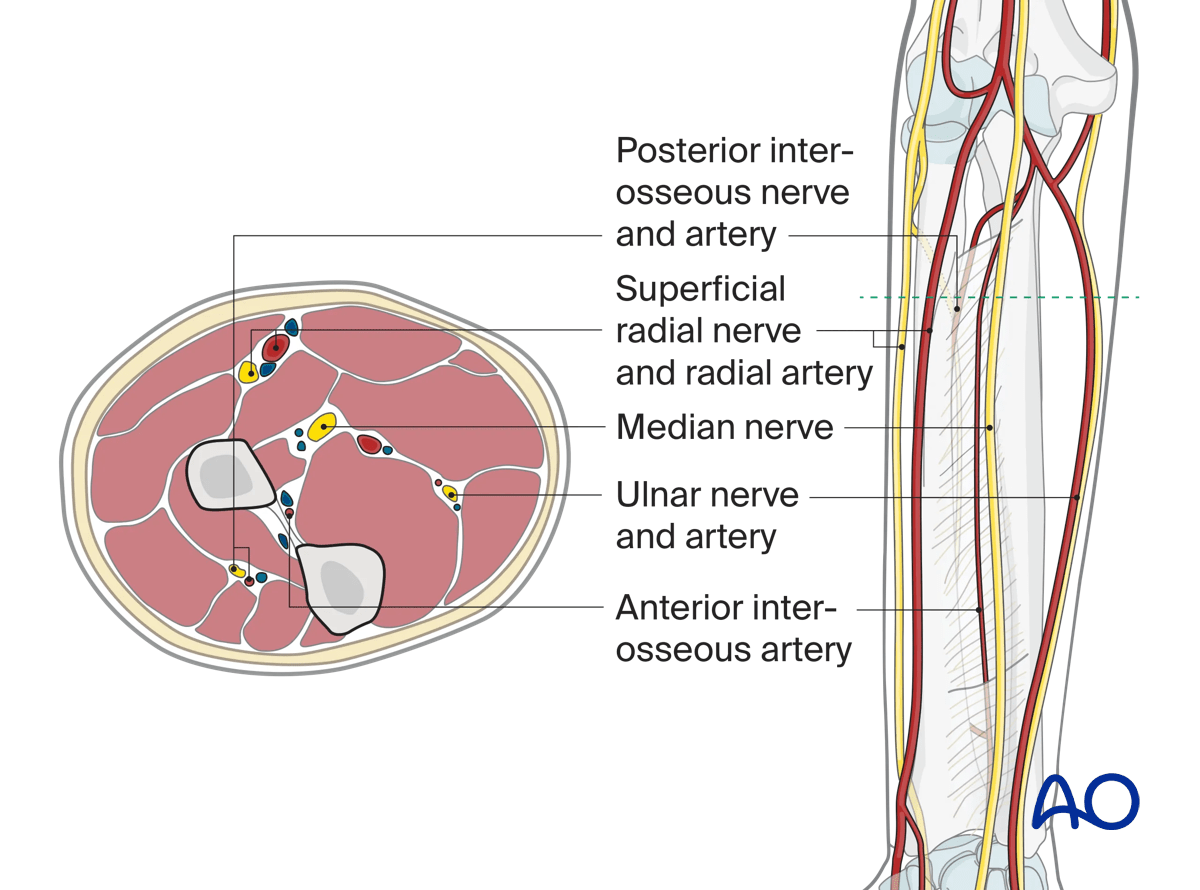

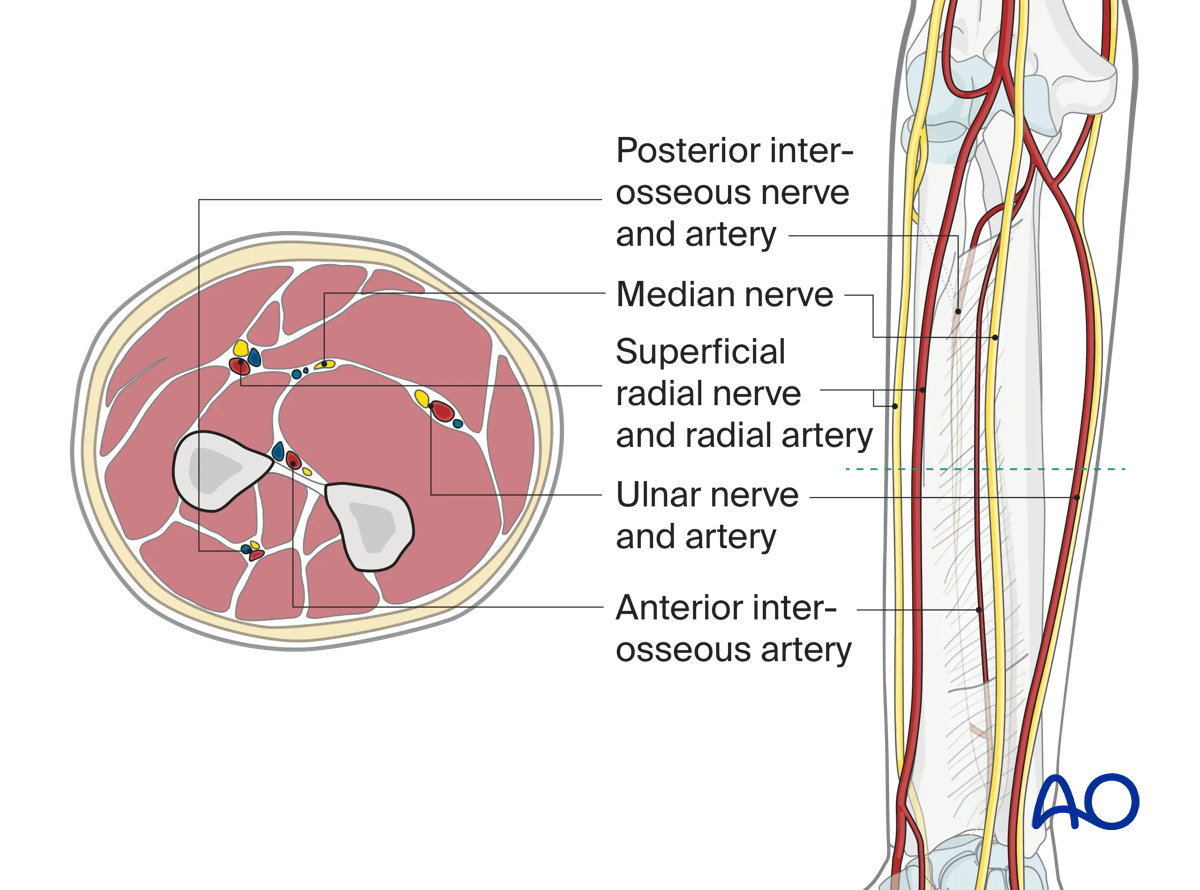

The neurovascular anatomy in the proximal forearm comprises the following:

- Posterior interosseous nerve and artery

- Superficial radial nerve and radial artery

- Median nerve

- Ulnar nerve and artery

- Anterior interosseous artery

Mid forearm

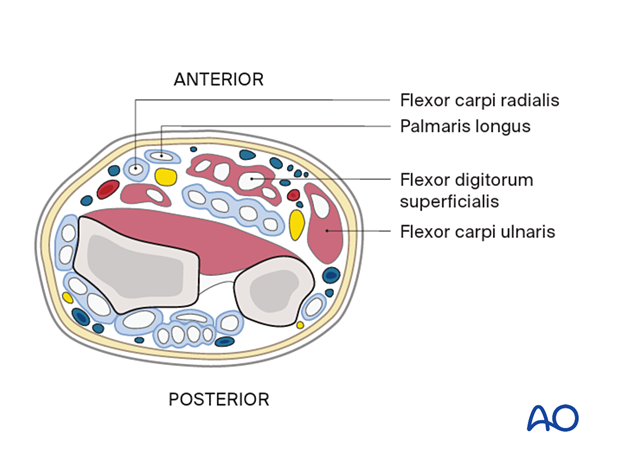

Superficial flexor compartmentThe muscles of the superficial flexor compartment in the mid forearm comprise the following:

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Pronator teres

- Flexor digitorum superficialis

- Flexor carpi ulnaris

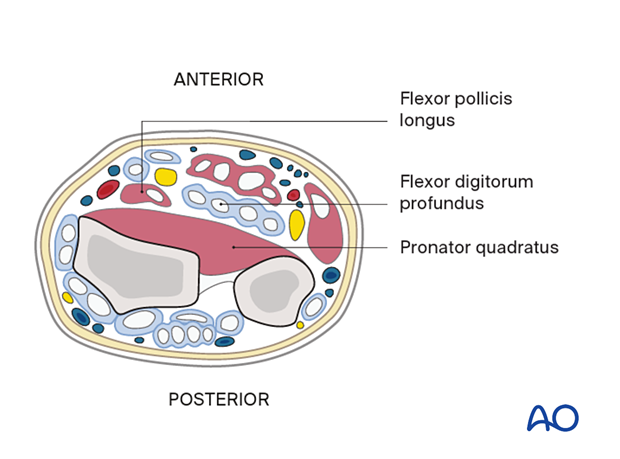

The muscles of the deep flexor compartment in the mid forearm comprise the following:

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Flexor digitorum profundus

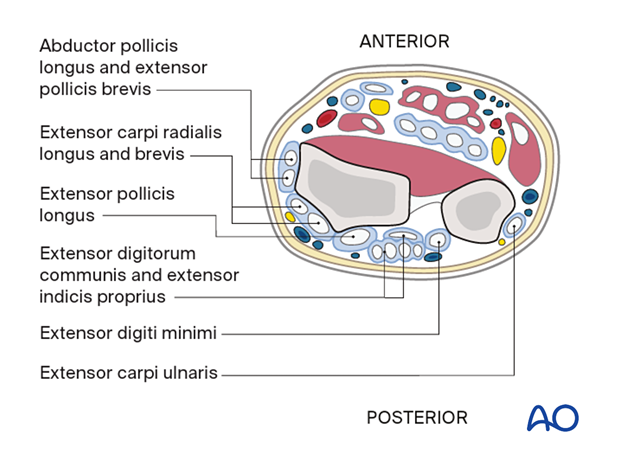

The muscles of the deep extensor compartment in the mid forearm comprise the following:

- Extensor pollicis brevis

- Abductor pollicis longus

- Extensor pollicis longus

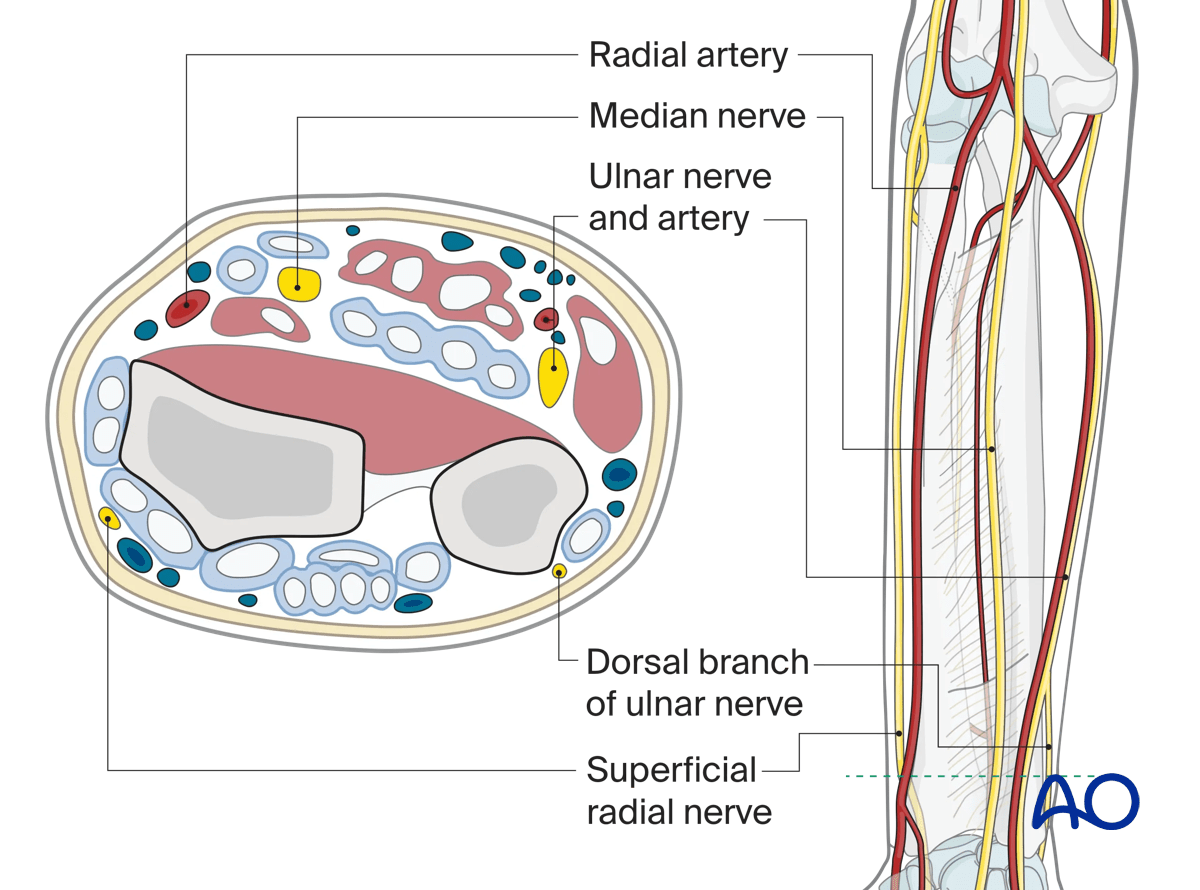

The neurovascular anatomy in the mid forearm comprises the following:

- Posterior interosseous nerve and artery

- Median nerve

- Superficial radial nerve and radial artery

- Ulnar nerve and artery

- Anterior interosseous artery

Distal forearm

Superficial flexor compartmentThe muscles and tendons of the superficial flexor compartment in the distal forearm comprise the following:

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor digitorum superficialis

- Flexor carpi ulnaris

Further information about the flexor compartment in the wrist and hand can be found here.

The muscles and tendons of the deep flexor compartment in the distal forearm comprise the following:

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Flexor digitorum profundus

- Pronator quadratus

The muscles and tendons of the extensor compartment in the distal forearm comprise the following:

- Abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis

- Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis

- Extensor pollicis longus

- Extensor digitorum communis and extensor indicis proprius

- Extensor digiti minimi

- Extensor carpi ulnaris

Further information about the extensor compartment in the wrist and hand can be found here.

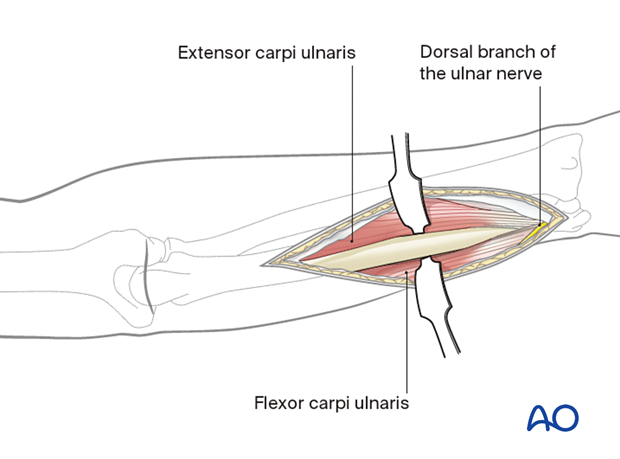

The neurovascular anatomy in the distal forearm comprises the following:

- Radial artery

- Median nerve

- Ulnar nerve and artery

- Dorsal branch of ulnar nerve

- Superficial radial nerve

6. Approaches to fasciotomy

There are three main compartments in the forearm:

- Mobile wad

- Anterior (ventral) compartment

- Posterior (dorsal) compartment

The approach to the relevant muscle compartment will be based on one of the standard surgical approaches in the forearm, respecting the important neurovascular structures.

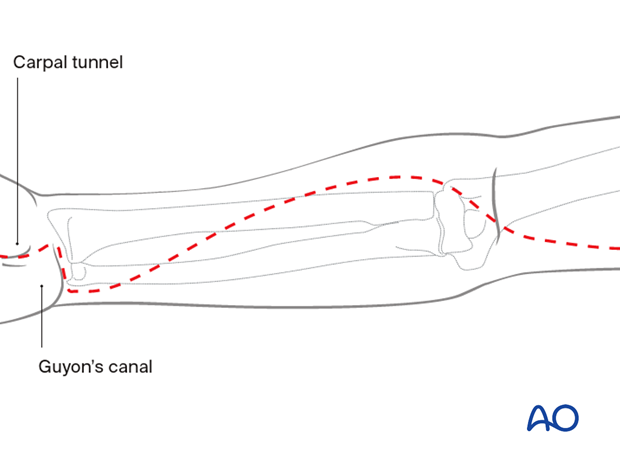

The procedure should include decompression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel and the ulnar nerve in the distal forearm and Guyon’s canal. Further information on this anatomical area can be found here.

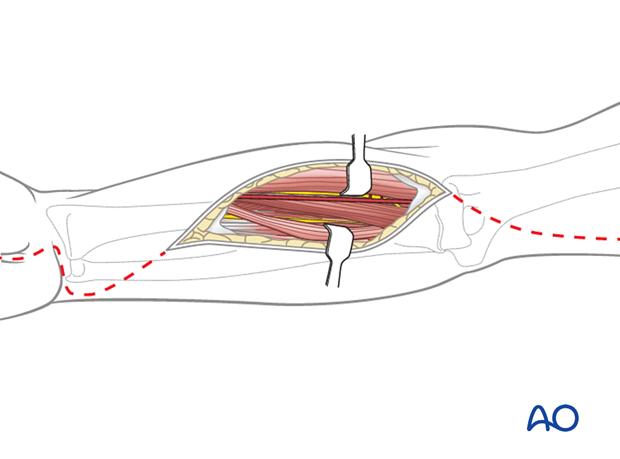

Anterior fasciotomy approach

The standard anterior fasciotomy incision extends over the carpal tunnel and Guyon's canal distally (in order to decompress the median and ulnar nerves), continues with a curved incision towards the radial side of the mid-forearm and back to the ulnar side of the proximal forearm. It may be extended proximally across the elbow if wider access is required.

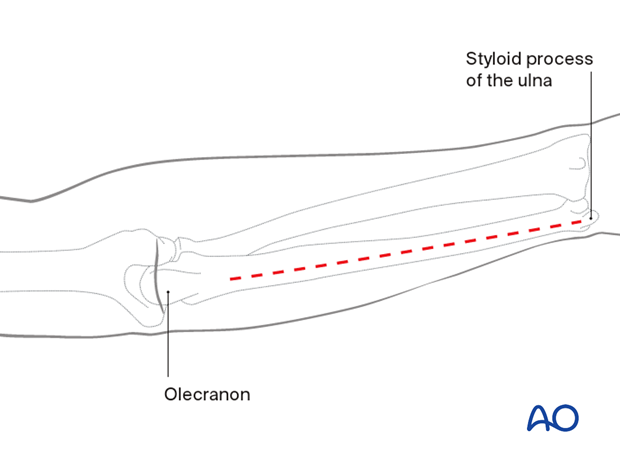

Posterior fasciotomy approach

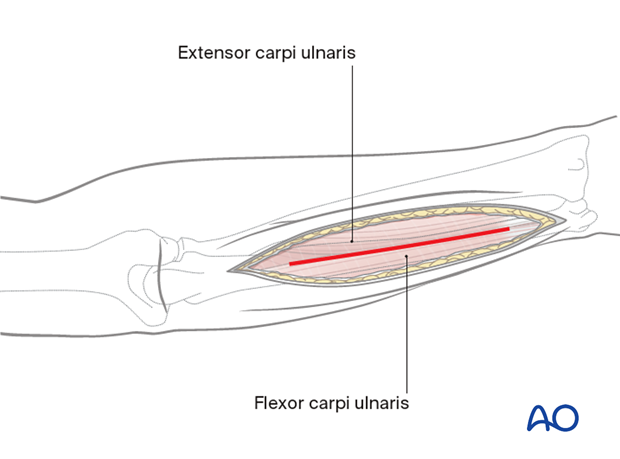

The standard ulnar approach is used.

The skin incision follows the subcutaneous border of the ulna, along a line drawn between the tip of the olecranon process and the ulnar styloid process.

The deep dissection should be carried out in the interval between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the extensor carpi ulnaris muscles.

7. Fasciotomy closure

Temporary soft-tissue management

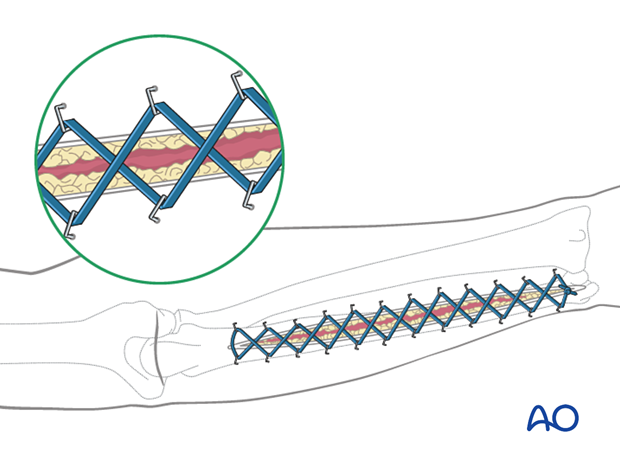

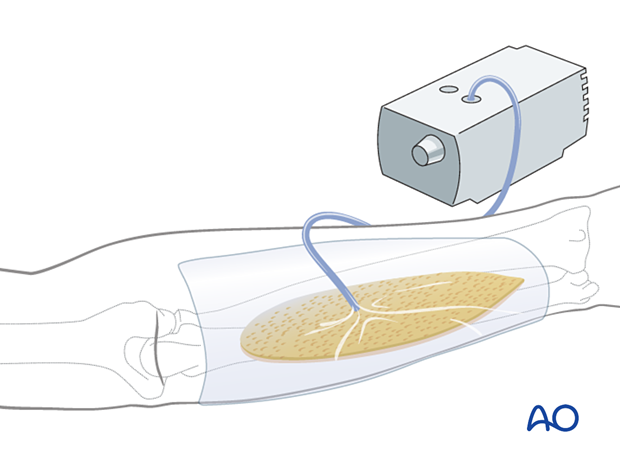

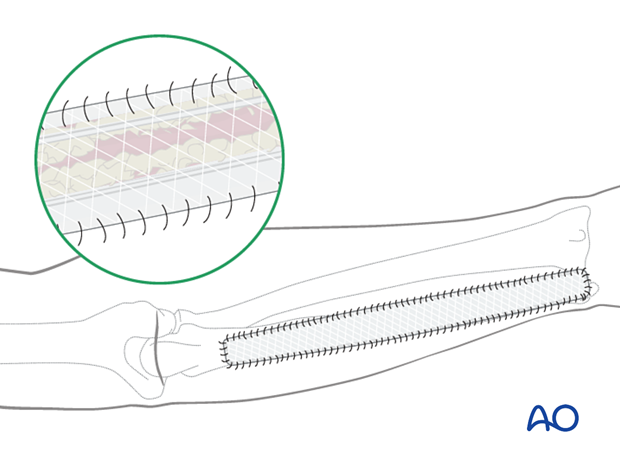

After a fasciotomy or fasciotomies have been performed, skin edges retract and can become difficult to close. Careful use of elastic retention sutures (elastic vessel loops woven through skin staples) can help counteract excessive skin contraction while still allowing the decompressed muscles to swell without any undue tension over them. Temporary coverage of the wounds can be obtained with either a wound vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device or with saline-soaked gauze bandages. These dressings or the wound VAC can be kept on until the patient returns for an attempt at secondary closure.

Delayed soft-tissue management: primary suture

If the swelling of the limb adequately decreases upon subsequent return to the operating room, primary closure of the fasciotomy wounds can occur. It is important to not perform primary closure if there is any concern about persistent swelling; secondary coverage options exist. In many instances, application of an incisional wound VAC can enhance wound healing.

Delayed soft-tissue management: secondary cover

If persistent swelling exists but wound closure is necessary, particularly for fractures that have been fixed, secondary wound coverage options are necessary. These include split thickness skin grafting, muscle flaps, or musculocutaneous flaps. In many instances continued use of wound VACs may be sufficient for wound healing.

It is important to provide soft-tissue cover over fractures that have been fixed in a timely manner to minimize the risk of subsequent infection.

8. Aftercare

Splintage

It is important to splint the elbow, forearm, and hand in a neutral position until soft tissue and skin closure has been achieved.

Further information about splintage can be found here.

- Circumferential casting should be avoided before skin closure due to the risk of persistent compartment syndrome

- Dynamic splintage should be considered after skin closure

Rehabilitation

Active range of motion of the elbow, wrist, and hand is performed as soon as possible. Passive mobilization is performed by physiotherapists if the patient is unable to participate.