Flexor tendon mechanism

1. Anatomy

Introduction

The flexor tendon system of the hand comprises tendons, synovial sheaths, pulleys, and muscles.

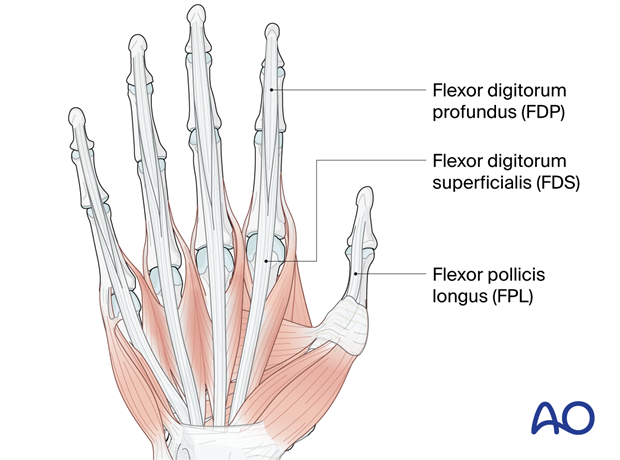

Flexor tendons

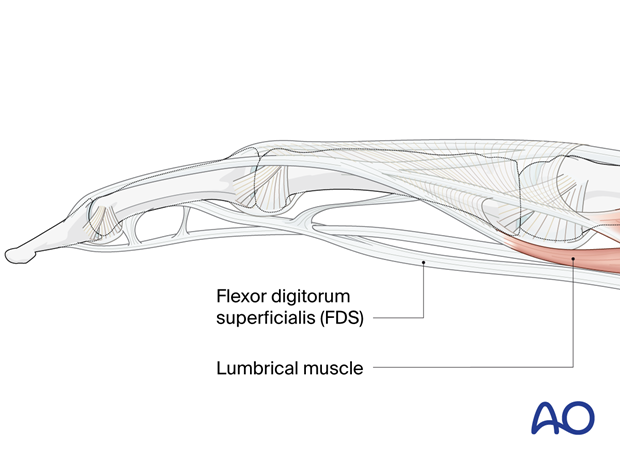

- Flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS): Superficial tendon, which splits at the level of the proximal phalanx and is attached laterally to the middle phalanx. It flexes the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

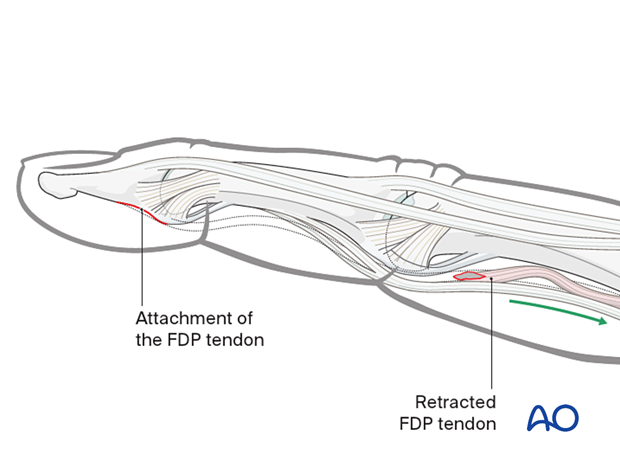

- Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP): Deeper tendon, which is running through the split of the FDS and is attached to the volar aspect of the distal phalanx. It flexes the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint as well as the PIP and MCP joints.

- Flexor pollicis longus (FPL): It is attached to the volar aspect of the distal phalanx of the thumb. It flexes its interphalangeal (IP) and MCP joints.

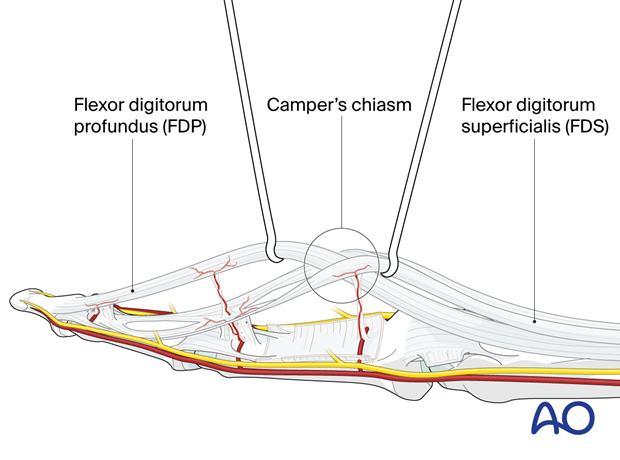

The FDP runs through the split of the FDS which creates a tendinous chiasm at the level of the PIP joint (Camper’s chiasm).

Synovial sheaths

Synovial sheaths enclose tendons, reducing friction and providing lubrication.

Blood supply occurs by diffusion through synovial sheath and direct vascular perfusion through vinculae.

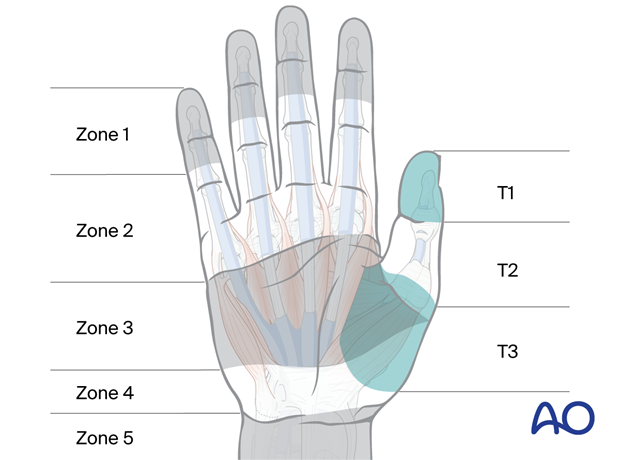

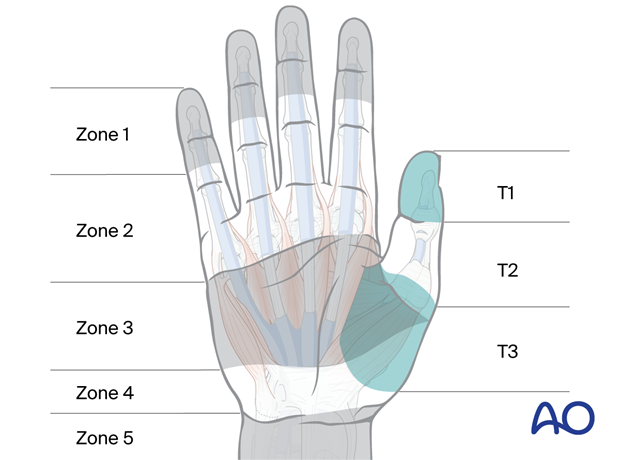

Zones 1–5 define specific sheath locations, crucial for injury classification:

- Zone 1: distal to FDS insertion

- Zone 2: no man’s land (containing both FDP and FDS)

- Zone 3: A1 pulley to distal transverse carpal ligament

- Zone 4: carpal tunnel (containing 9 tendons and the median nerve)

- Zone 5: carpal tunnel to forearm (spaghetti wrist)

For the thumb, the zones are similar to the fingers:

- Zone T1: distal to A2 pulley

- Zone T2: from A2 to distal A1 pulley

- Zone T3: from distal A1 pulley to carpal tunnel

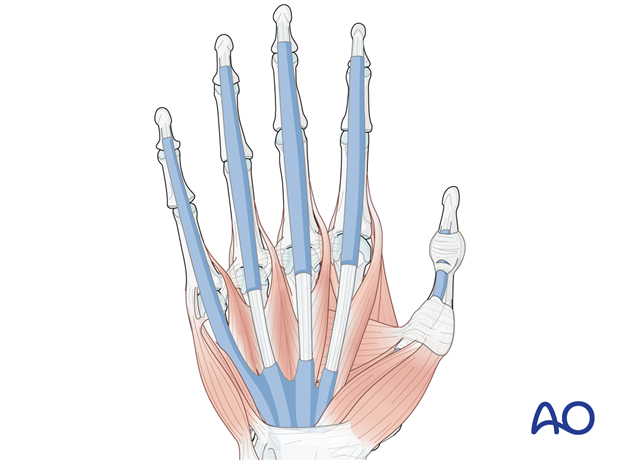

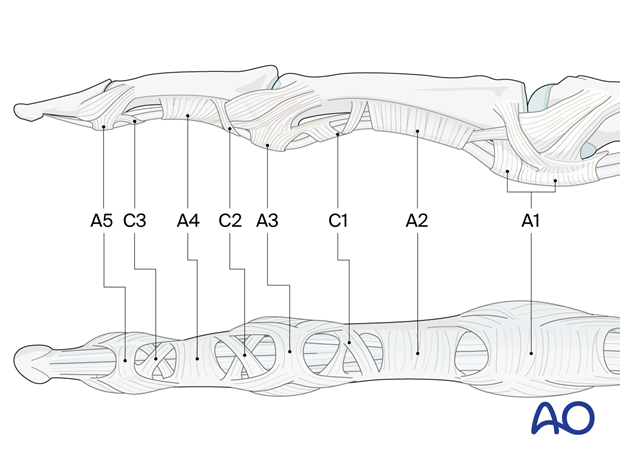

Pulleys

Pulleys are fibrous bands anchoring tendons to underlying structures.

In the long fingers, annular pulleys (A1–A5) and cruciate pulleys (C1–C4) guide tendon movement and increase mechanical advantage.

In the thumb, there are 3 annular pulleys and an oblique pulley.

Ligaments of Landsmeer

The ligaments of Landsmeer support coordination and synchronization of the PIP and DIP joint movements (Balakrishnan et al. 2019).

2. Biomechanics

The flexor tendon mechanism works by pulling the flexor tendons towards the forearm, which causes the fingers to flex at the phalangeal and MCP joints.

- Finger flexion occurs through coordinated muscle contraction and tendon gliding within sheaths.

- Pulleys act as fulcrums, increasing force and efficiency of flexion.

- Different pulley zones play distinct roles in specific joint flexion.

The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) flexes all the joints including the DIP joint.

The flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) flexes the MCP and PIP joints only. Together with the FDP, it provides for fine tuning of a powerful grip strength.

The lumbrical muscle flexes the MCP joint and may contribute to smoothing the extension movement while resisting ulnar deviation of the extending finger. This also allows for flexion at the MCP joints with extension at the PIP and DIP joint.

3. Lesions

Introduction

Lesions of the flexor tendon mechanism can occur at any level, but they are most common at the MCP joint and the PIP joint. The most common cause of flexor tendon lesions is trauma, such as a laceration, bite, or crush injury. However, they can also be caused by inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis.

Injury classification after Kleinert and Verdan:

- Zone 1 (distal to FDS): jersey finger

- Zone 2 (no man’s land): traditionally, poor outcomes because of fibrosis and bulky repair

- Zone 3 (A1 to distal transverse carpal ligament): associated to neurovascular injuries

- Zone 4: carpal tunnel (9 tendons and median nerve)

- Zone 5 (carpal tunnel to forearm): neurovascular injuries

Injury classification for the thumb:

- Zone T1: FPL tendon only

- Zone T2: traditionally poorer outcome because of fibrosis and bulky repair

- Zone T3: potential thenar muscle involvement

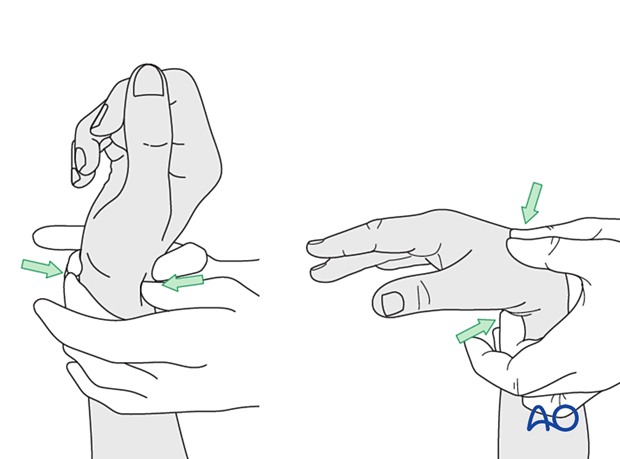

Principles of assessment

- History: mechanism of injury, time since injury, functional limitations

- Examine for associated neurovascular injury.

- Physical examination: active and passive flexion, resting finger posture, palpation for tenderness or gaps, sensation testing, tenodesis effect

- Special tests for revision surgery: Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s maneuver, passive tenodesis test (evaluation of flexor tendon laceration with the tenodesis effect)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of flexor tendon lesions is by clinical examination. The associated fractures or fracture-dislocations are typically confirmed by x-rays supplemented by MRI if indicated.

- Imaging studies: x-rays to rule out fractures, ultrasound/MRI to visualize tendon integrity and sheath involvement

- Electrodiagnostic studies (for revision surgery): assessment of nerve function and potential nerve injuries

4. Management of flexor tendon lesions

Introduction

Acute injuries:

- Nonsurgical management: Immobilization and splinting is possible in select cases with partial tendon lesions in uncontaminated wounds.

- Surgical management: Early surgical repair is often required to optimize healing potential particularly in contaminated or complex wounds.

Chronic injuries:

- In selected cases with specific functional losses, reconstruction procedures or tendon transfers may be indicated.

The management of flexor tendon lesions depends on the severity of the lesion. Partial lesions (less than 50% of the tendon) may be treated with splinting and rehabilitation. Partial tendon lesions more than 50% should be treated as complete ruptures with surgical repair.

The proximal tendon is retracted towards the palm and adhesions with the fibrosis form within the sheath rapidly. This requires urgent surgical treatment.

Penetrating skin injuries are treated as for all open wounds by debridement, irrigation, and antibiotic cover.

Associated fractures or fracture-dislocations are treated according to the indications given in the respective module of Surgery Reference.

Tendon injuries are treated by debridement, irrigation, and either primary repair or secondary reconstruction if the wound is contaminated and cannot be adequately cleaned for primary repair.

Associated digital nerve injuries are treated according to the chapter on Digital nerve lesions in the hand.

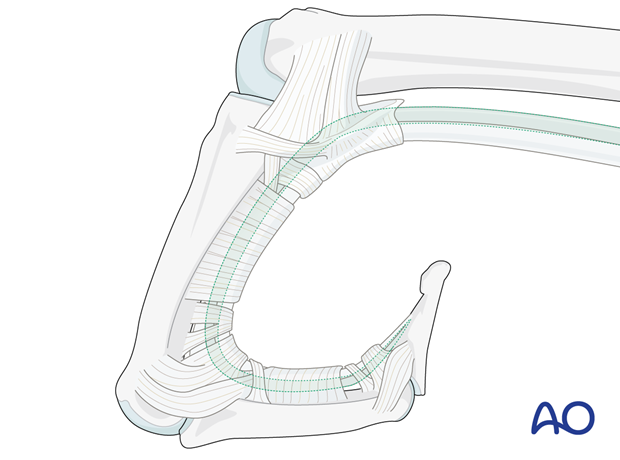

Tendon repair technique

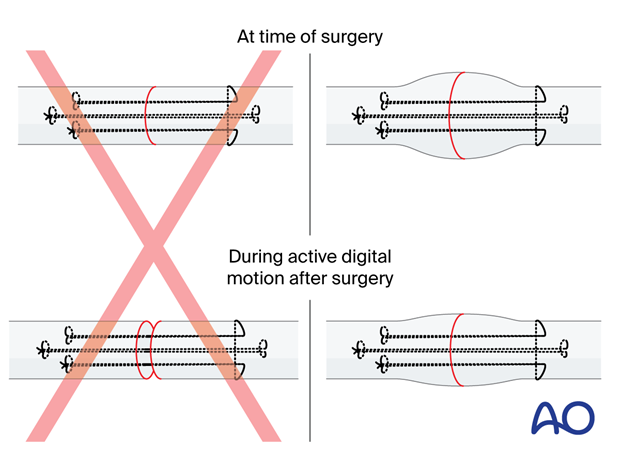

The current standard of treatment for flexor tendon repair is 6-strand core suture and venting of the pulley.

Tendon repair in zones other than zone 2 has generally better outcome and less risk of retraction or adhesion.

In zone 2, the standard tendon repair technique is using 4- or 6- strand sutures. The preferred option is with 6 strand sutures to allow early active mobilization (see Chinen et al 2021).

The use of WALANT enables the surgeon to assess the tendon repair intraoperatively, especially the gliding functionality and tension at the repair site while actively flexing. This allows for later early active mobilization and reducing the risk of stiffness.

Pulley repair and reconstruction

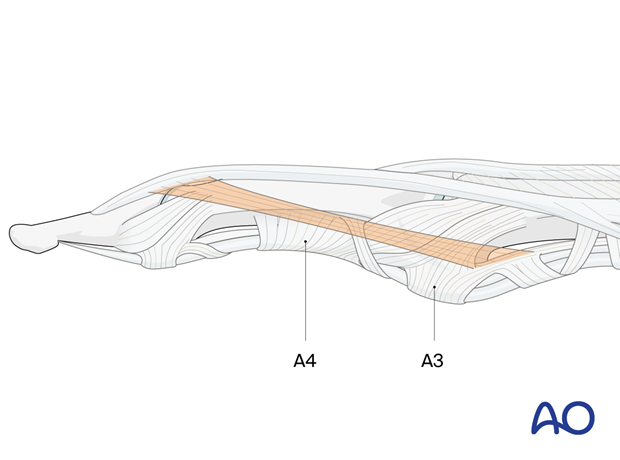

The fibrous flexor sheath including the pulleys is considered crucial for optimal flexor tendon stability and gliding (Zafonte et al. 2014, Jain et al. 2000).

The A2 and A4 pulleys have been considered to be the most important. Reconstruction of these pulleys is indicated for optimal flexor tendon function.

However, venting (division of) the A2 or A4 pulley to decompress the flexor sheath for optimal perfusion of the repair region can be considered if the other pulleys are intact and part of the A2 pulley is preserved (Tang 2018).

5. Healing and rehabilitation

Introduction

The healing of flexor tendon lesions is a slow process that can take several months. Specialized rehabilitation is an important support for the healing process to restore the function of the hand (Klifto et al. 2019, Neiduski et al. 2019, Higgins et al. 2016).

There are two pathways of healing:

- Intrinsic healing: proliferation of tenocytes and extracellular matrix

- Extrinsic healing: cellular invasion from surrounding synovium (this dominates when sheath is injured) favors fibrosis

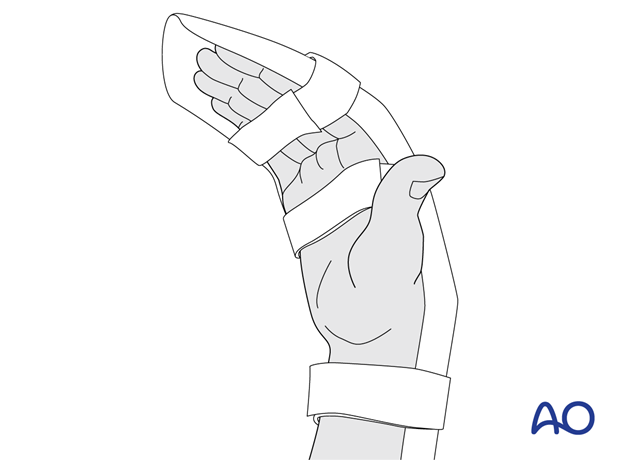

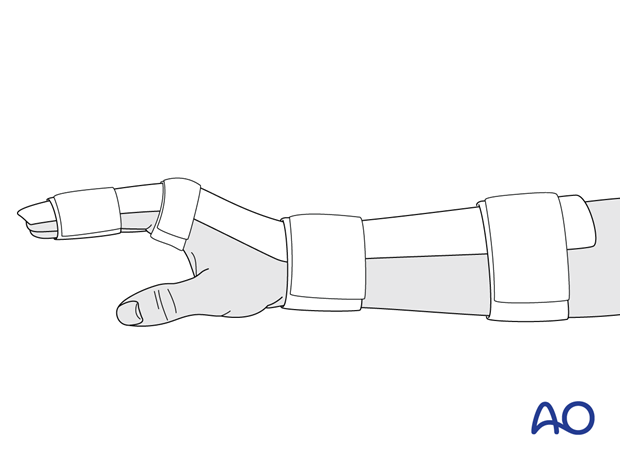

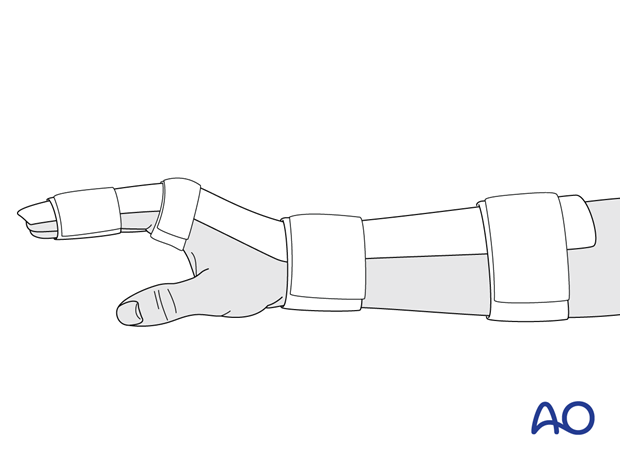

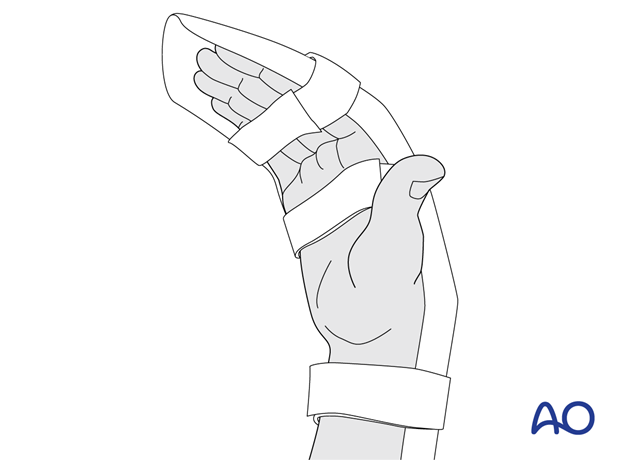

Splinting and mobilization

Splinting is used to protect the flexor tendon and prevent it from rerupturing. The type of splint used will depend on the location of the lesion.

Early controlled motion therapy is crucial for prevention adhesions and to optimize return of function.

Static splinting may be used to maintain tendon alignment and protect healing repairs.

- Dorsal blocking splints with flexion of the wrist facilitate passive (therapist assisted) mobilization.

- The patient can actively mobilize the affected tendon through a safe but limited range of movement (Chevalley et al. 2022).

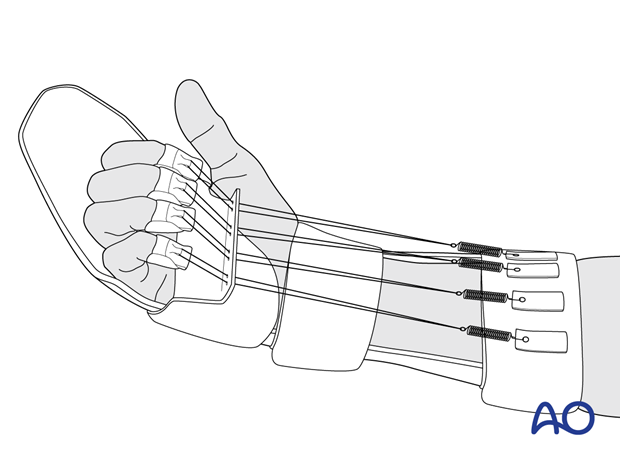

Dynamic splinting encourages controlled motion and active tendon gliding.

- Dynamic splints facilitate controlled movement of the hand, specific to the injury and are most commonly used in reconstruction procedures.

- Stiffness due to adhesions may be avoided by using this splinting technique.

- Patients are placed in a splint with the wrist in neutral position, the MCP joints at 30°, and the IP joints fully extended.

- Active mobilization of the affected tendons is encouraged within the limits of the splint (Klifto et al. 2019).

- Patients are placed in a dorsal blocking splint.

- Combined passive flexion-extension mobilization (therapist assisted) is performed until the end of the third week.

- After week 3, active range of motion is initiated.

- Patients are placed in a dorsal splint with the wrist in 30° palmar flexion and the MCP joints in 50° to 60° flexion. Full active extension of the IP joints is allowed.

6. References

- Balakrishnan TM, Subbaraj H, Jaganmohan J. Anatomy of Landsmeer Ligaments—Redefined. Indian J Plast Surg. 2019 May;52(2):195–200.

- Chevalley S, Tenfält M, Åhlén M, et al. Passive Mobilization With Place and Hold Versus Active Motion Therapy After Flexor Tendon Repair: A Randomized Trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47(4):348–357.

- Chinen S, Okubo H, Kusano N, et al. Effects of Different Core Suture Lengths on Tensile Strength of Multiple-Strand Sutures for Flexor Tendon Repair. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2021 Jan; 3(1): 41–46.

- Higgins A, Lalonde DH. Flexor Tendon Repair Postoperative Rehabilitation: The Saint John Protocol. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016 Nov;4(11):e1134.

- Jain A, Nanchahal J. The Flexor Tendon Pulley System in the Hand - Aspects of Rehabilitation and its Importance in Flexor Tendon Function. Br J Hand Ther. 2000;5(3):80–84.

- Klifto CS, Bookman J, Paksima N. Postsurgical Rehabilitation of Flexor Tendon Injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2019 Aug;44(8):680–686.

- Neiduski RL, Powell RK. Flexor tendon rehabilitation in the 21st century: A systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2019 Apr–Jun;32(2):165–174.

- Tang JB. Recent evolutions in flexor tendon repairs and rehabilitation. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2018 Jun;43(5):469–473.

- Zafonte B, Rendulic D, Szabo RM. Flexor Pulley System: Anatomy, Injury, and Management. J Hand Surg Am. 2014 Dec;39(12):2525–2532.