Extensor tendon mechanism

1. Anatomy

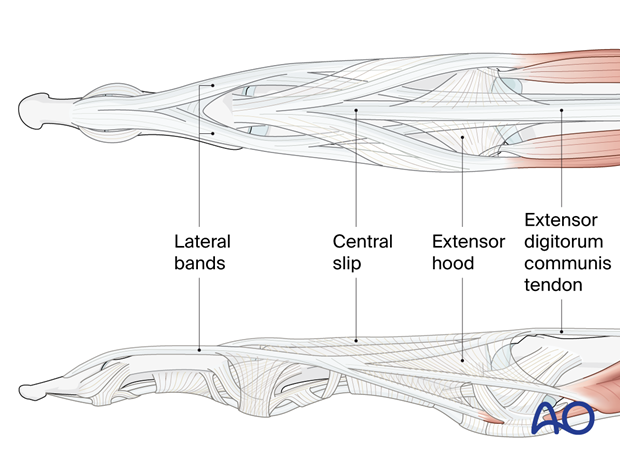

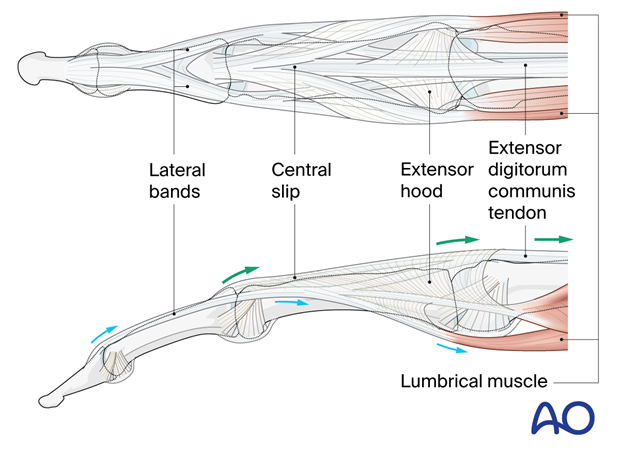

The extensor tendon mechanism is a complex structure that is responsible for extending the fingers. It is composed of the following components:

- Extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendon: This tendon originates from the common extensor muscle on the forearm and divides into three slips at the level of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint. Each slip inserts into the base of the corresponding proximal phalanx through the extensor hood.

- Extensor indicis tendon: This tendon originates from a different muscle and insert into the base of the 2nd proximal phalanx.

- Extensor digiti minimi (EDM) tendon: This tendon originates from a separate muscle and inserts into the base of the 5th proximal phalanx.

- Central slip: This is a thin band of tendon that passes from the base of the middle phalanx to the dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx. It is responsible for extending the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint.

- Lateral bands: These are two bands of tendon that arise from the lateral aspects of the middle phalanx and insert into the base of the distal phalanx. They are responsible for extending the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.

Clinical anatomy

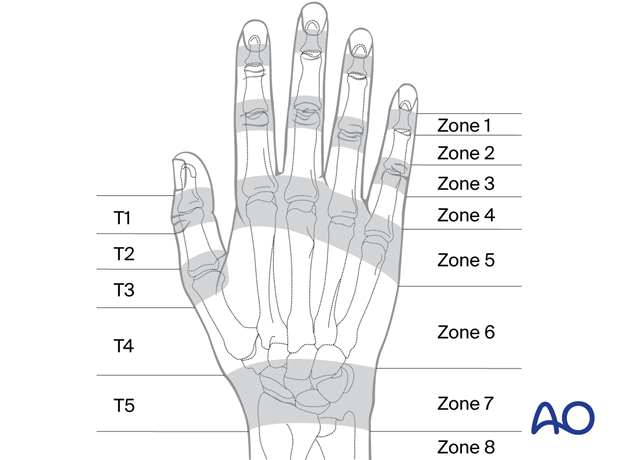

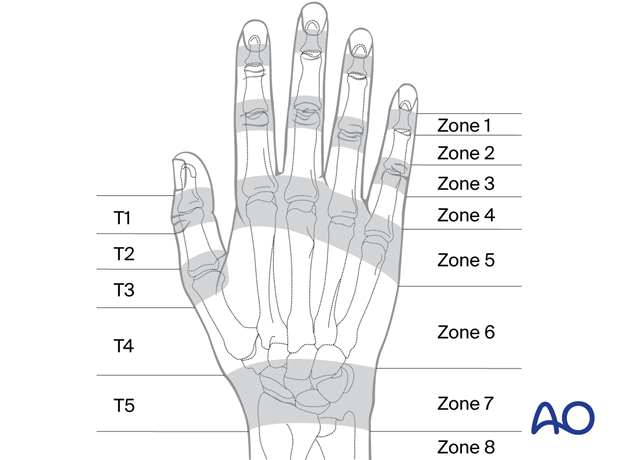

Each region or zone of the extensor surface of the hand is subject to characteristic injuries:

- Zone 1: distal interphalangeal joint

- Zone 2: middle phalanx

- Zone 3: proximal interphalangeal joint

- Zone 4: proximal phalanx

- Zone 5: metacarpophalangeal joint

- Zone 6: metacarpal

- Zone 7: carpal bones and wrist joint

- Zone 8: distal forearm

- Zone 9: proximal forearm

For the thumb, the zones are similar to the fingers:

- Zone T1: interphalangeal joint

- Zone T2: proximal phalanx

- Zone T3: metacarpophalangeal joint

- Zone T4: metacarpal

- Zone T5: radiocarpal joint

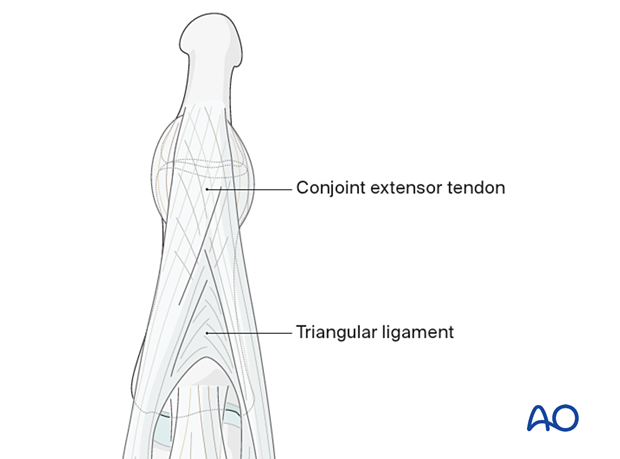

In zone 2 at the level of the middle and distal phalanx, the lateral bands come together in the conjoint extensor tendon. Note the decussation of the fibers within the conjoint extensor tendon and also within the triangular ligament.

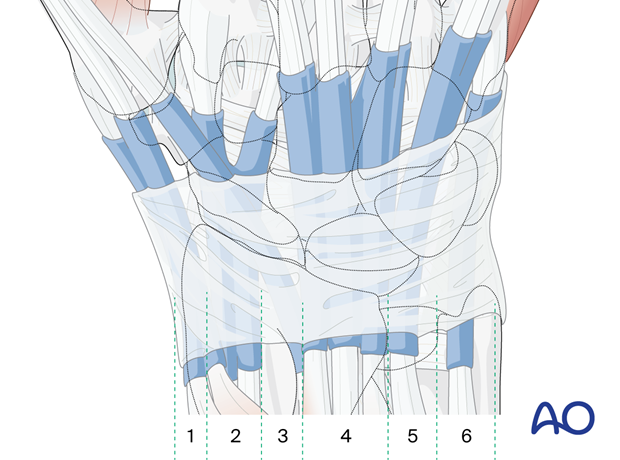

Extensor sheaths and retinaculum

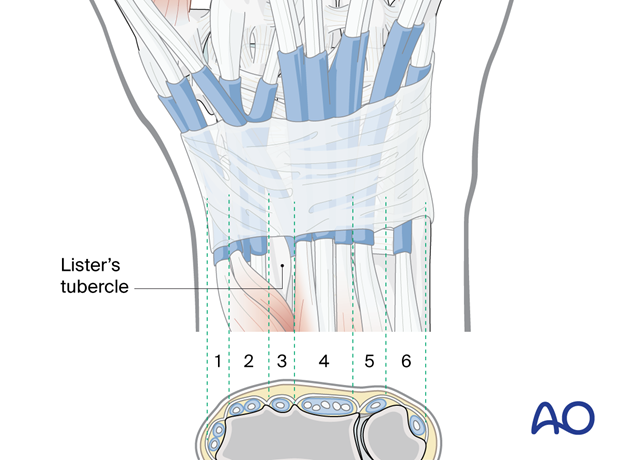

There are six extensor compartments on the dorsum of the radiocarpal region:

- The 1st compartment contains the tendons of abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB)

- The 2nd compartment contains the extensors carpi radialis longus and brevis (ECRL and ECRB, respectively)

- The 3rd compartment contains the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL)

- The 4th compartment contains the tendons of the extensor indicis and extensor digitorum communis (EDC) (the PIN nerve can be found here)

- The 5th compartment contains the tendon of the extensor digiti minimi (EDM)

- The 6th compartment contains the tendon of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU)

The extensor retinaculum is a condensation of the deep forearm fascia and covers the extensor compartments at the level of the carpus.

The retinaculum defines the extensor compartments through deep attachments to the radius and ulna.

- Clinical significance: It is important to repair the extensor retinaculum after exposure of the extensor compartments to restore extensor function of the fingers.

2. Biomechanics

Fingers

The extensor tendon mechanism works by pulling the extensor tendons (black arrows) towards the forearm, which causes the fingers to extend at the MCP joint. The central slip is particularly important for extending the PIP joint, while the lateral bands are more important for extending the DIP joint.

The lumbrical muscle may contribute to smoothing the extension movement and resists ulnar deviation of the extending finger (red arrows). This also allows for flexion at the MCP joints with extension at the PIP and DIP joint.

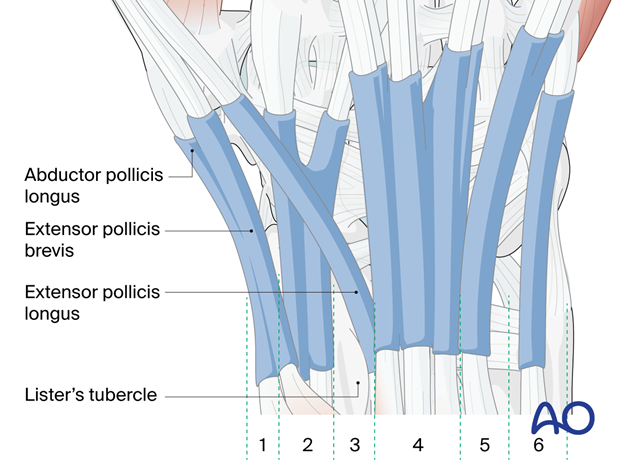

Thumb

The extensor tendon mechanism of the thumb consists of three tendons: abductor pollicis longus (APL), extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and extensor pollicis longus.

The first two tendons are in the 1st compartment and responsible for radial abduction of the metacarpal of the thumb.

The Lister’s tubercle acts as a pulley for the extensor pollicis longus in the 3rd compartment at the level of the distal radius. This allows for true dorsal extension of the metacarpal and MCP of the thumb.

- Clinical significance: It is important to restore the pulley function of Lister’s tubercle during fixation of distal radial fractures.

3. Lesions

Introduction

Lesions of the extensor tendon mechanism can occur at any level, but they are most common at the MCP joint and the PIP joint besides the mallet finger at the DIP joint. The most common cause of extensor tendon lesions is trauma, such as laceration, bite, or crush injury. However, they can also be caused by inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis.

The extensor indicis is frequently injured either directly or by attrition in proximity to a distal radial fracture.

The extensor digiti minimi may be injured directly or by attrition in proximity to a distal ulnar fracture.

Principles of assessment

The posture of the finger will indicate the level, extent, and type of lesion:

- Eg, flexion of the DIP in association with an inability to actively extend the joint indicates a lesion of the attachment of the extensor tendon to the base of the distal phalanx (mallet deformity).

Examine for evidence of penetrating injuries:

- Eg, look for skin laceration over a distal metacarpal shaft fracture with angulation and extensor tendon tear.

Examine for underlying fracture or fracture-dislocation.

Examine for active movement based on knowledge of the extensor tendon mechanism.

- Look for signs of extension deficit.

Examine for associated neurovascular injury.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of extensor tendon lesions is by clinical examination. The associated fractures or fracture-dislocations are typically confirmed by X-rays supplemented by MRI if indicated.

- Zone 1: Mallet finger (bony or tendinous)

- Zone 2: Tendon injuries (usually lacerations)

- Zone 3: Central slip injury (boutonniere)

- Zone 5: Bite injuries + sagittal band injury (boxer’s knuckle)

- Zone 6: Tendon injuries (usually lacerations)

- Zones 7–9: usually tendinous or myotendinous junction lacerations in the forearm

Management

The management of extensor tendon lesions depends on the severity of the lesion. Mild lesions may be treated with splinting and rehabilitation. However, more severe lesions may require surgery to repair the tendon.

Penetrating skin injuries are treated as for all open wounds by debridement, irrigation, and antibiotic cover.

Associated fractures or fracture-dislocations in Zones 1 and 3 are treated according to the indications given in the respective module of Surgery Reference.

Tendon injuries (lacerations) are treated by debridement, irrigation, and either primary repair or secondary reconstruction if the wound is contaminated and cannot be adequately cleaned for primary repair.

Associated nerve injuries are treated according to:

Healing and Rehabilitation

The healing of extensor tendon lesions is a slow process that can take several months. Specialized rehabilitation is an important support for the healing process to restore the function of the hand.

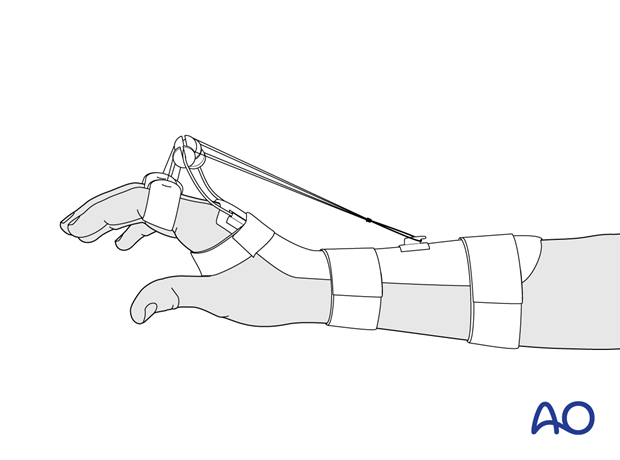

Splinting is used to protect the extensor tendon and prevent it from re-rupturing. The type of splint used will depend on the location of the lesion.

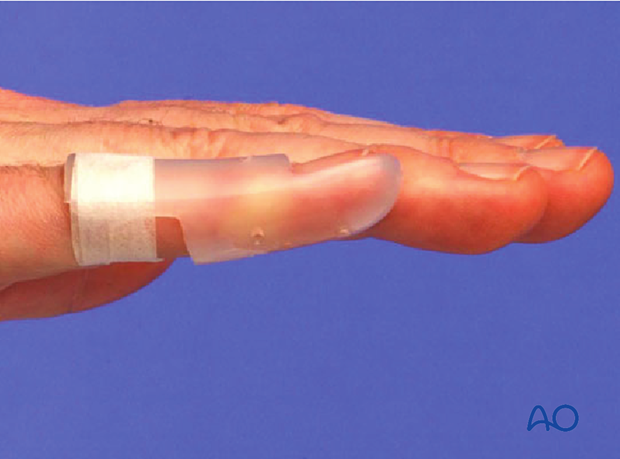

Zone 1: dorsal hyperextension splint (immobilizing the DIP)

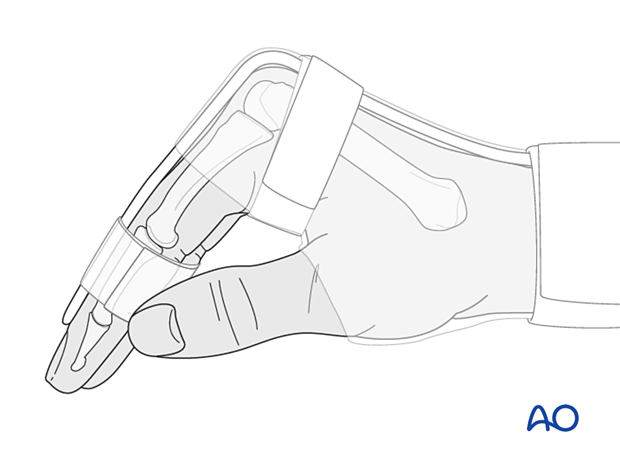

Zone 2–5: dorsal stack splint with hand in Edinburgh position (PIP and MCP joint immobilization)

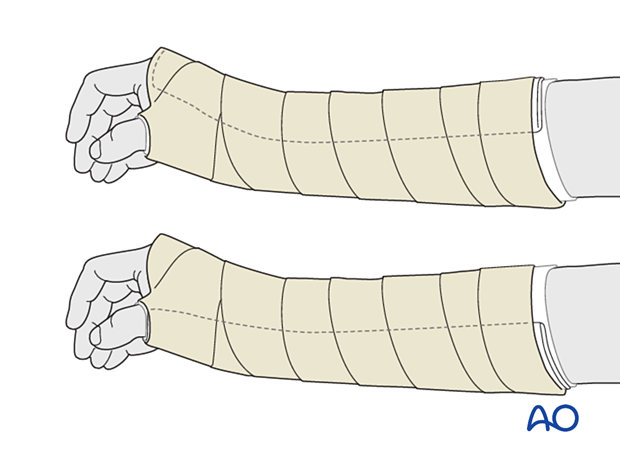

Injuries in zones 6–9 can be managed with a dorsal or palmar below-elbow splint with the wrist in up to 15° extension.

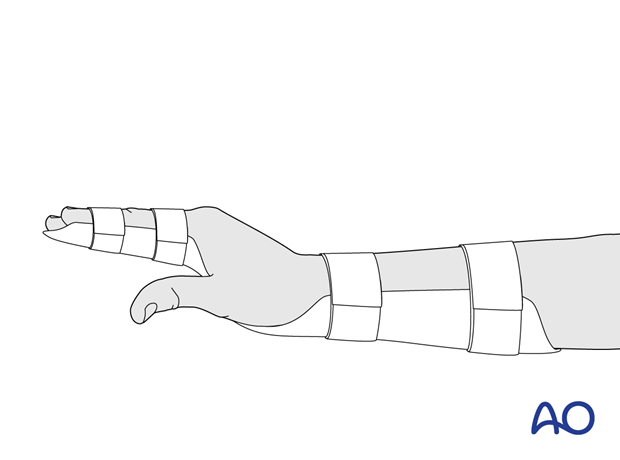

Static splints are used to immobilize the hand and prevent movement, eg, a palmar splint for the forearm and hand to include the index finger and thumb may be indicated to protect a primary repair of the extensor indicis with an associated distal radial fracture.

Dynamic splints encourage controlled movement of the hand, specific to the injury. This can help to avoid stiffness.

4. References

- Bennett DJ, Bango J, Rothkopf DM. Hand Therapy after Flexor and Extensor Tendon Repair: Assessing Predictors of Loss to Follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023 Apr 26;11(4):e4941.

- Colzani G, Tos P, Battiston B, et al. Traumatic Extensor Tendon Injuries to the Hand: Clinical Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Surgical Procedure Review. J Hand Microsurg. 2016 Apr;8(1):2–12.

- Elfenbein DH, Rettig ME. The digital extensor mechanism of the hand. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2000;59(4):183–188.

- Giele H, Sammut D. The Functional Anatomy And Assessment Of The Extensor Mechanism. Br J Hand Ther. 2006;11(4):104–110.

- Harris Jr C, Rutledge Jr GL. The Functional Anatomy of the Extensor Mechanism of the Finger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:713–726.

- Matzon JL, Bozentka DJ. Extensor Tendon Injuries. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:854–861.

- Rockwell WB, Butler PN, Byrne BA. Extensor tendon: anatomy, injury, and reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Dec;106(7):1592–1603.

- Sammut D. Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Extensor Tendon System. In: Boyce DE, Giddins G, Shewring DJ. Tendon Disorders of the Hand and Wrist. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2022.

- Schubert CD, Giunta RE. Extensor tendon repair and reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2014 Jul;41(3):525–531.

- Thompson ST, Wehbé MA. Extensor physiology in the hand and wrist. Hand Clin. 1995 Aug;11(3):367–371.

- Tubiana R, Valentin P. The anatomy of the extensor apparatus of the fingers. Surg Clin North Am. 1964 Aug;44:897–918.

- Wehbé MA. Anatomy of the extensor mechanism of the hand and wrist. Hand Clin. 1995 Aug;11(3):361–366.

- Yoon AP, Chung KC. Management of Acute Extensor Tendon Injuries. Clin Plast Surg. 2019 Jul;46(3):383–391.