ORIF - Bridge plating

1. Principles

General considerations

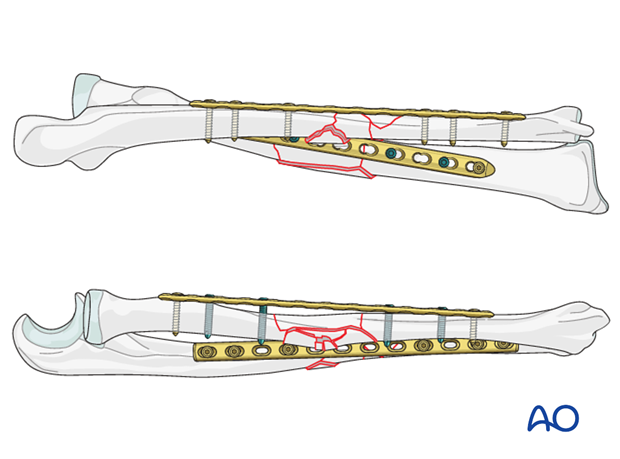

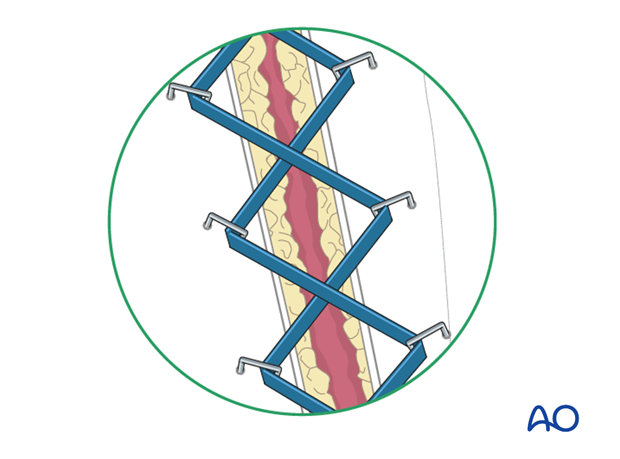

Bridge plating uses the plate as an extramedullary splint fixed to the two main fragments while the complex fracture zone is left virtually untouched (bridged), thereby minimizing damage to the blood supply of the intermediate fragments.

Reduction of the bridged fragments will not be anatomical but the procedure is based on the restoration of the relationship of the two main fragments in terms of length, rotation and axis. In these cases, x-rays of the uninjured contralateral forearm, including both wrist and elbow, are useful as a template for restoring length and rotation.

Soft tissues should be handled with meticulous attention to the vascularity of the fracture zone.

Particularly in open fractures, a single approach to both bones should be avoided if possible since excessive additional stripping would be necessary. Furthermore, this can lead to an increased risk of infection, nonunion, and heterotopic bone formation.

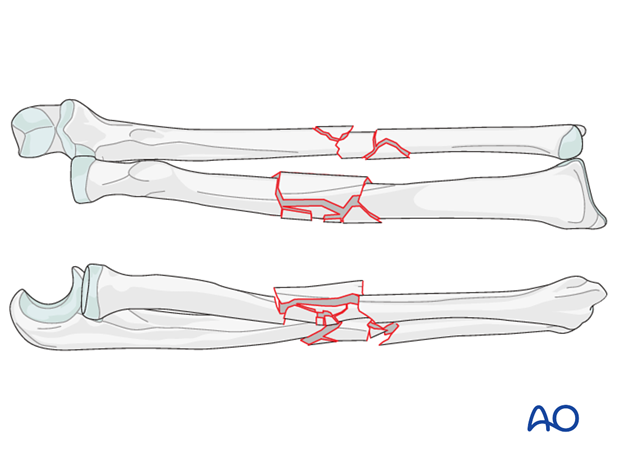

In fragmentary segmental fractures of both bones, the multifragmentary zone in each bone precludes anatomical reduction and absolute stability.

We shall consider only these fractures in this section but for the management of a segmental forearm fracture refer to that section.

Order of fixation

- The less comminuted fracture should be reduced and provisionally fixed first. In cases where the degree of comminution is similar in both bones, one should start with the fixation of the ulna since it is less curved than the radius and restoration of the anatomical alignment is easier.

In most cases, anatomical reduction of the intermediate fragments is neither an objective nor desirable. Rather, the achievement of correct length, rotation and axial alignment of the main fragments is the goal; this can be achieved by relying on indirect signs: - As a second step, the more comminuted bone is reduced and provisionally fixed:

- If needed, revision of reduction of either bone and adjustment of the provisional fixation is performed.

- Finally, both bones are fixed definitively and the ranges of forearm rotation assessed.

Estimation of alignment by matching the surface features of the main shaft fragments

Examination of the gross appearance of the forearm

Intraoperative radiographic examination and comparison with the preoperative images of the uninjured forearm, which must include the elbow and the wrist.

Check length and rotation

Provisionally fix with a bridging plate

The illustrated procedure that follows will start with the ulna.

Choice of implant

The requirements for internal fixation of fragmentary segmental fractures include:

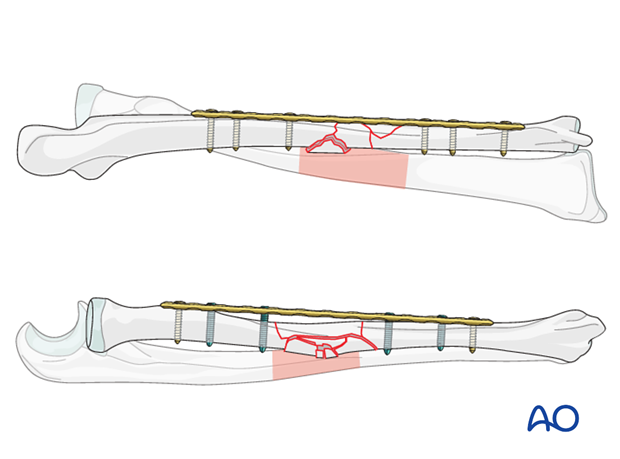

- The plate should be long enough to span the comminuted zone, and to provide at least a four-hole segment over each main fragment, giving the possibility for at least three bicortical screws in each main fragment.

- Well-spaced screws to distribute the stresses on the bone-implant composite for each main fragment

- For ulnar fractures, other than those with a very short main fragment, the limited contact dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP) is the preferred implant.

- In osteoporotic patients, or with a very short terminal segment, an angular stable plate is an option for the ulna, in which case at least one of the two screws on each side of the fracture needs to be a locking screw.

- The morphology of the radius is more complex and if available, the locking compression plate (LCP) offers considerable advantages, avoiding the need for precise anatomical contouring.

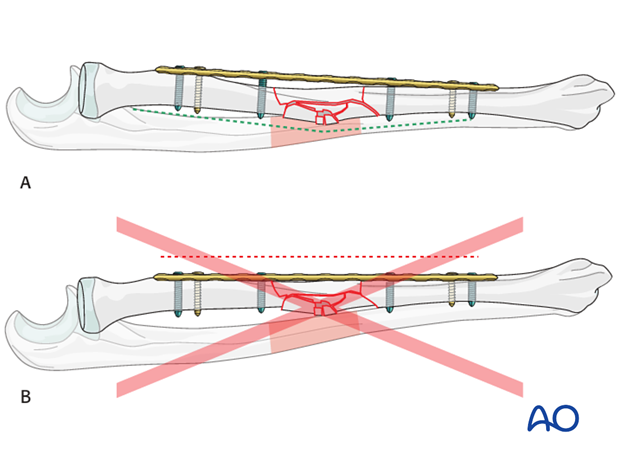

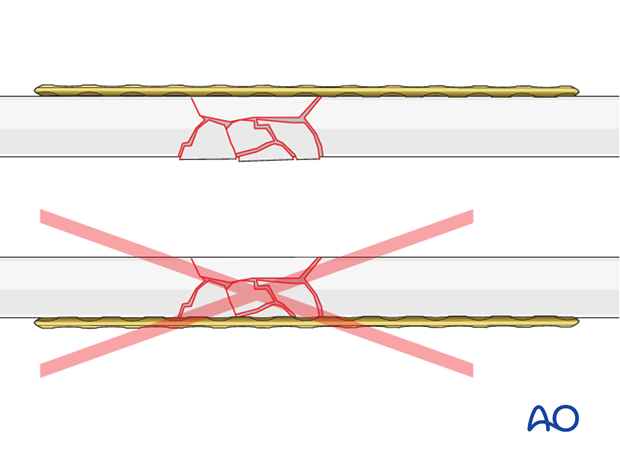

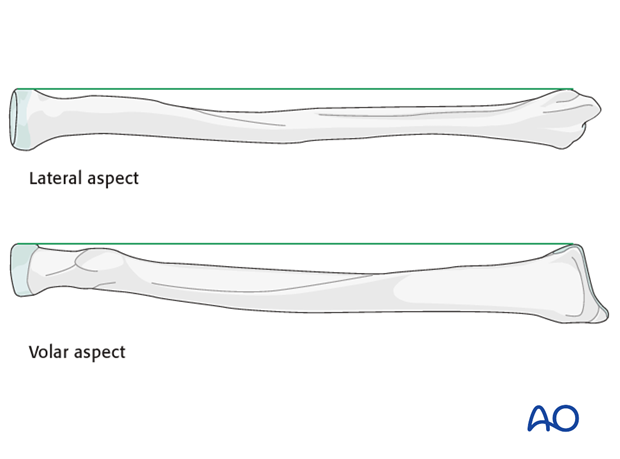

In the radius, a long and straight LCP is placed over a curved bone. Careful attention is paid to the preservation of the radial curve (A). The radial anatomical curve should not be compromised to fit the shape of the plate (B).

The disadvantage of the locked internal fixators is that such plates are difficult to bend.

Preservation of the ulnar anatomy is less problematic, since the ulna is less curved than the radius. The LC-DCP may need some minimal contouring in order to avoid distortion of the normal morphology.

Approaches

When both bones need to be reduced and fixed, a separate approach to each bone should be considered in order to reduce the risk of heterotopic bone formation.

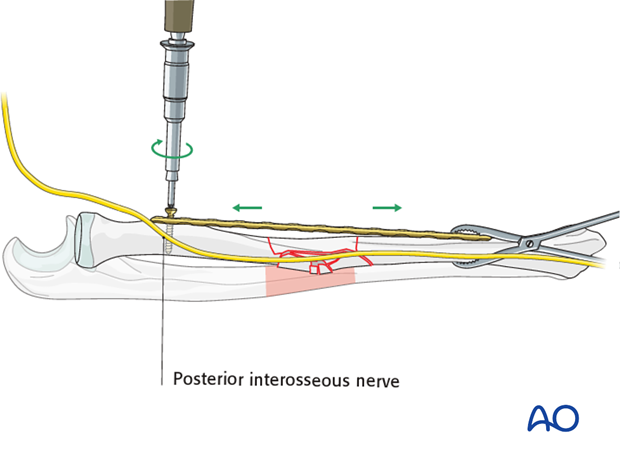

There are two standard approaches to the radius, the anterior (Henry volar) approach and posterolateral (Thompson dorsolateral) approach.The Henry approach is extensile and can be used to expose the entire length of the radius. It is therefore often preferred in multifragmentary fractures where extension of the approach may be necessary.For proximal radial shaft fractures, the Henry approach is often safer as it carries less risk to the posterior interosseous nerve, which crosses over the proximal radius within the supinator muscle. The Thompson approach requires extremely careful identification, protection and handling of the nerve.

In mid and distal shaft fractures, either approach can be used depending on the fracture configuration and the surgeon’s preference.

The ulna is exposed by the standard subcutaneous approach between the flexor and extensor muscle compartments.

In certain proximal fragmentary segmental injuries, the combined posterior (dorsal) approach is preferred by some surgeons.

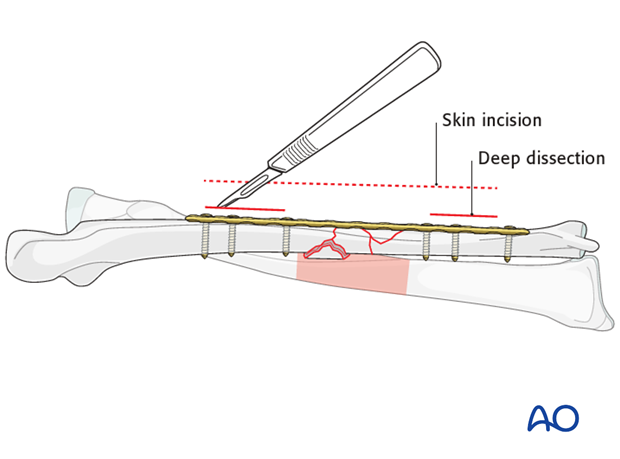

Extent of surgical approach (dissection)

The skin incision should be long enough to expose the intact segments of bone, in order to allow adequate fixation of the bridging plate to each main fragment, and to avoid injury to important neurovascular structures. For example, care should be taken not to injure the posterior interosseous nerve when the Henry approach is extended proximally; similarly care should be taken not to endanger the ulnar neurovascular bundle in the extension of the ulnar incision distally.

Despite the long skin incision, minimal dissection should be performed in the fracture zone.

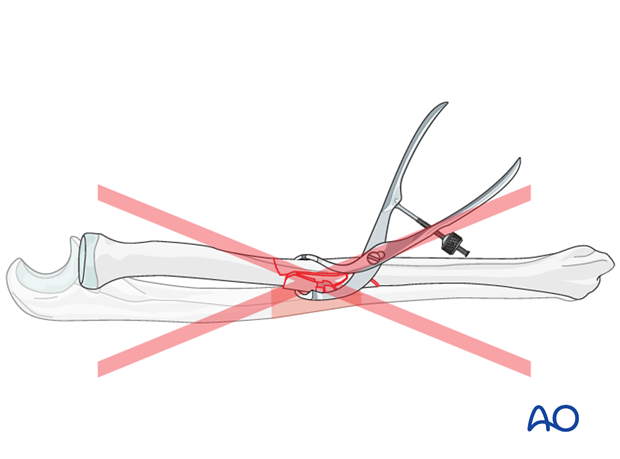

Soft-tissue considerations in comminuted zone

Avoid the placement of instruments, retractors, bone clamps, or fingers around the comminuted zone.

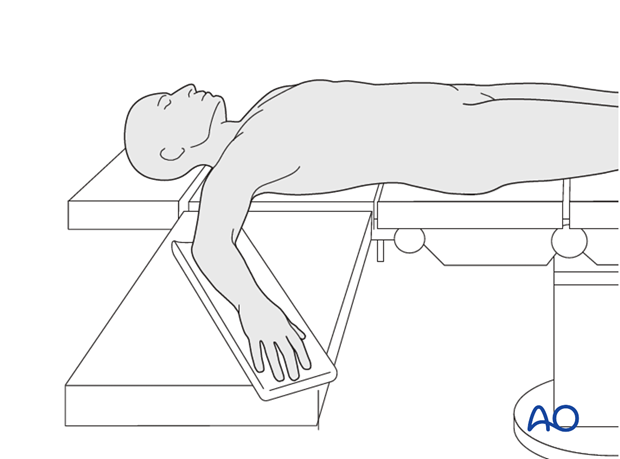

2. Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

3. Plate position, length and number of screws

Optimal plate position – general considerations

Choose the surface of the bone which is the least comminuted. It is essential, especially in high energy fracture patterns, that adequate soft-tissue coverage be available.

In many cases, soft-tissue coverage and comminution patterns will dictate plate position, rather than biomechanical considerations.

The selection of the optimal plate position will influence the approach chosen.

Avoid any additional injury to the soft tissue over the multifragmentary zone. In addition to preserving the vascularity of the fracture zone, containment of the intermediate fragments within their soft-tissue envelope will also aid their reduction.

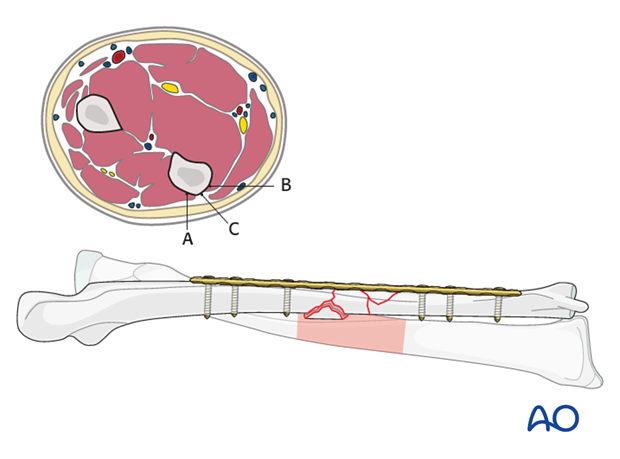

Plate position on ulna

To minimize interference with the soft-tissue envelope in the multifragmentary zone, the approach goes between the extensor and flexor muscle compartments and avoids stripping of the dorsal and volar aspects of the bone. A convenient location for the plate is on the dorsal aspect of the bone, but if hardware prominence is a likely problem, slight adjustment of position is acceptable. This will also permit better soft-tissue coverage of the hardware by one of the muscles.

The plate on the ulna can be positioned either under the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (A), under the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (B), or in the interval between them (C).

In the following procedure, we demonstrate the plate positioned deep to the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (A).

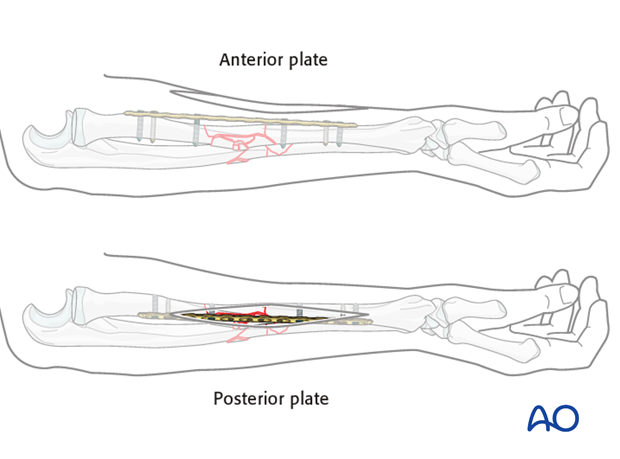

Plate position on the radius

The choice of plate position will normally be influenced by the fracture pattern and will determine the approach. However, associated soft-tissues considerations may prevent placing the plate in the optimal biomechanical position.

The plate may be applied to either the anterior or posterior surface of the radius.

If a more extensile exposure is necessary, the Henry approach is chosen and therefore the plate will be placed on the anterior surface.

In the following procedure, we illustrate the plate application to the anterior surface.

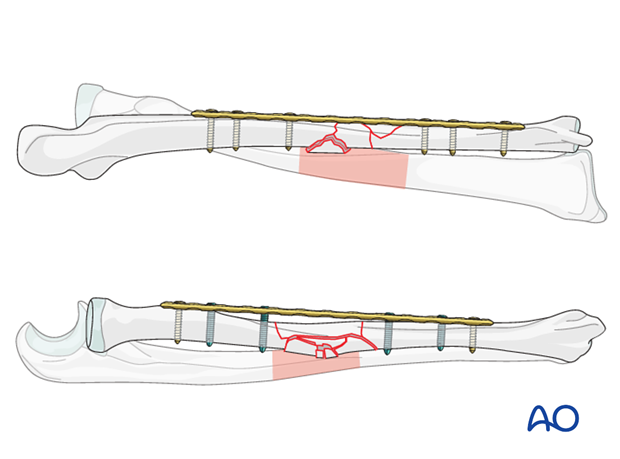

Plate length and number of screws

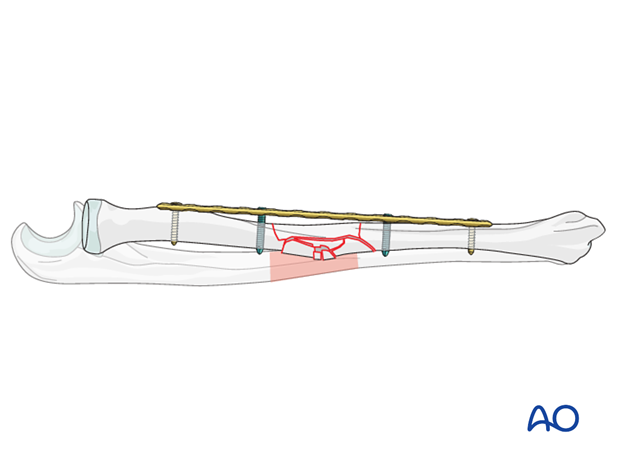

In the forearm, three bicortical screws are required in each main fracture fragment due to the high torsional stresses. For biological reasons, not every plate hole should be occupied by a screw. Therefore, plates that offer at least 4 holes over each main fragment should be used.

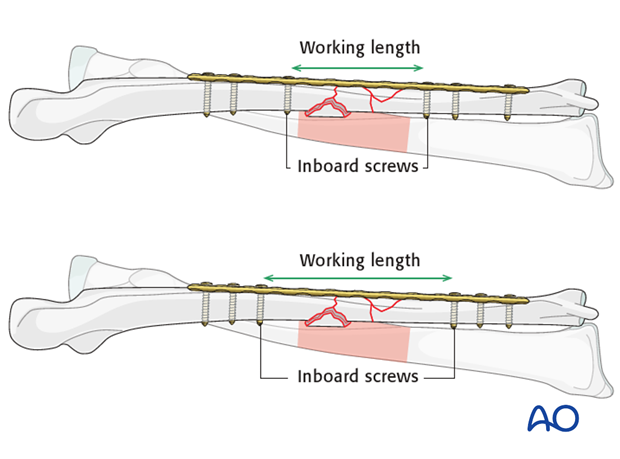

Working length considerations

Too great a working length increases the interfragmentary motion and can result in excessive callus formation which is undesirable in the forearm as it may compromise range of rotational motion.

Too short a working length increases the stresses on that portion of the plate and can risk implant fatigue.

In bridge plating, the working length of the segment of the plate spanning the multifragmentary zone can be reduced by placing, the “inboard” screws in each main fragment as near to the intermediate segment as possible. On the other hand, greater separation of the inboard screws increases the working length.

4. Reduction and preliminary fixation of the ulna

Reduction

The aim of reduction is to restore normal length, axis, and rotational alignment. Several techniques are available to assist in achieving the best possible reduction. Since the ulna is a straight bone, usually simple maneuvers are sufficient, such as:

- Manual traction and applying clamps onto the main fracture fragments with the aid of a plate

- Temporary external fixation, or a small distractor

- Reduction by help of the plate and distraction using a laminar spreader and an independent screw (push-pull technique)

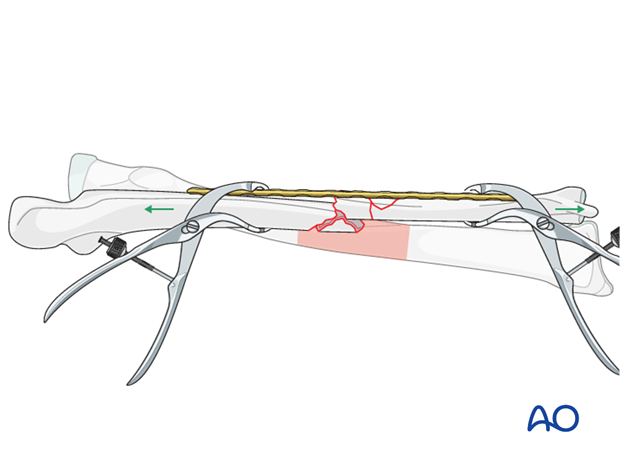

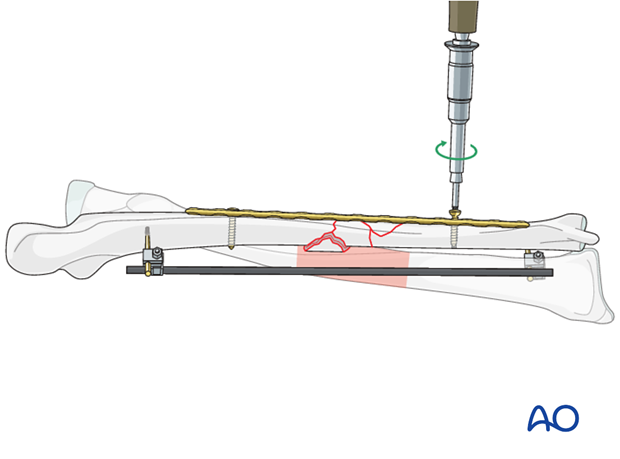

Manual traction and applying clamps onto the main fracture fragments with the aid of a plate

As dissection avoids the comminuted zone, bone clamps can safely be applied to the main fragments avoiding the fracture zone. Manual traction is then applied. Use the plate as a template for reduction while alternately applying traction and clamping, until reduction has been achieved.

With the forceps holding the reduction, a screw is inserted into each main fragment.

At that time, fine tuning of the reduction can still be achieved. Once reduction is completely satisfactory (clinically and radiographically), a second screw is inserted into each main fragment.

The forceps can now be removed.

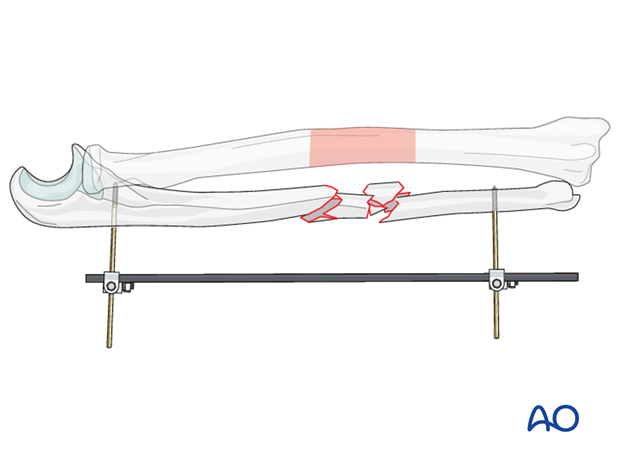

Temporary external fixator or small distractor

A single tube external fixation may be sufficient to achieve distraction of the straight ulnar bone. Alternatively, a small distractor can be used.

Insert one 3 or 4 mm threaded pins into the ulnar ridge of each main fragment, in the same plane, and connect them with a single bar (preferably radiolucent). Make sure to place them so that they will not compromise later plate placement.

Distract the main fragments and when correct length and rotation have been restored, tighten the clamps.

With the fixator in situ, preliminary fixation of the plate to ulna is achieved by inserting 1 screw into each main fracture fragment.

At that time, fine tuning of the reduction can still be achieved. Once reduction is completely satisfactory (clinically and radiographically), a second screw is inserted into one main fragment, the fixator bar is loosened and a second screw is inserted into the other main fragment.

The threaded pins are now removed.

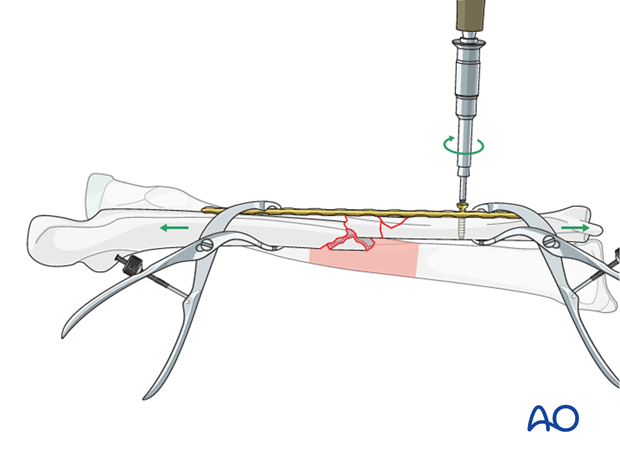

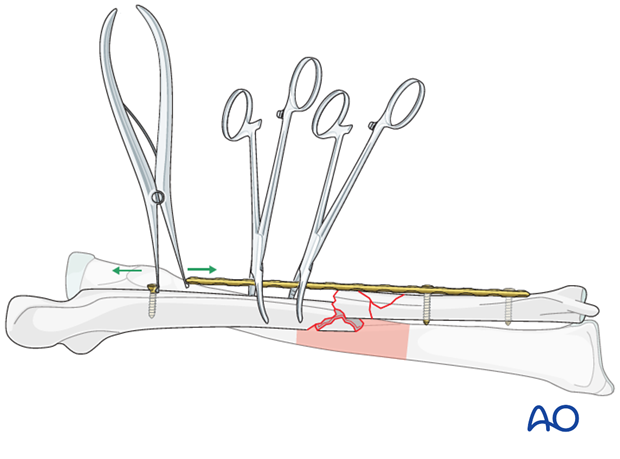

Reduction using the plate and distraction with a laminar spreader against an independent screw (push-pull technique)

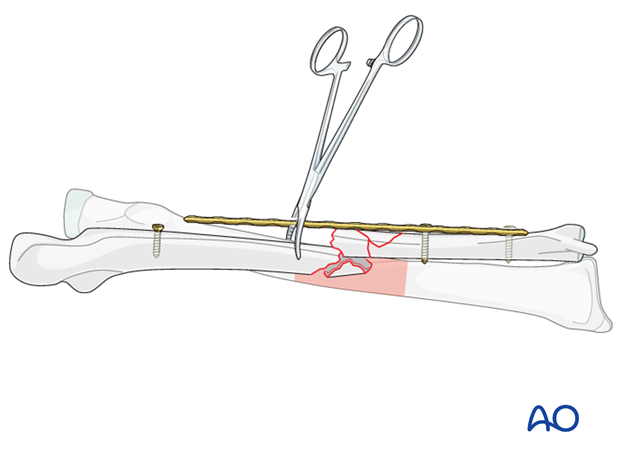

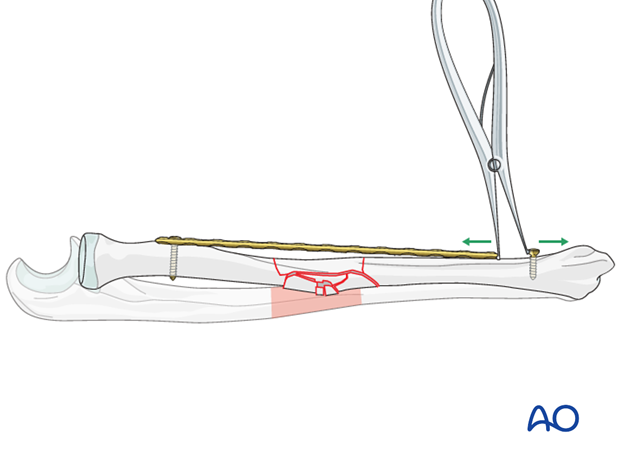

Attach the plate to one main fracture fragment with either two screws or one screw plus a bone forceps. Insert an independent screw into the other main fragment a short distance (1.5 – 2 cm) beyond the end of the plate.

A loosely applied bone forceps maintains the alignment of the plate and the mobile main fragment.

Check that rotational alignment is correct.

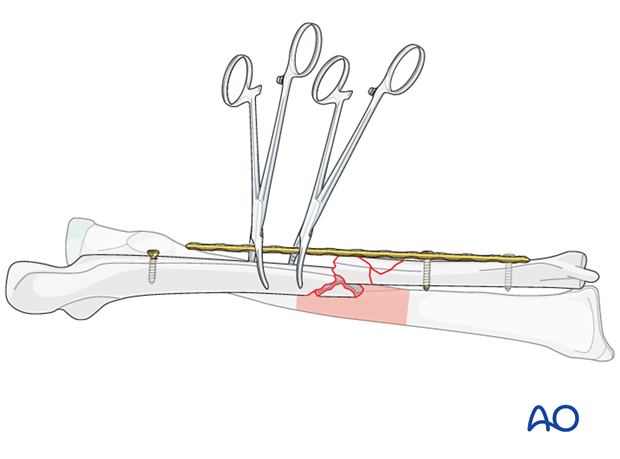

A second, loosely applied forceps may augment the maintenance of plate/fragment alignment.

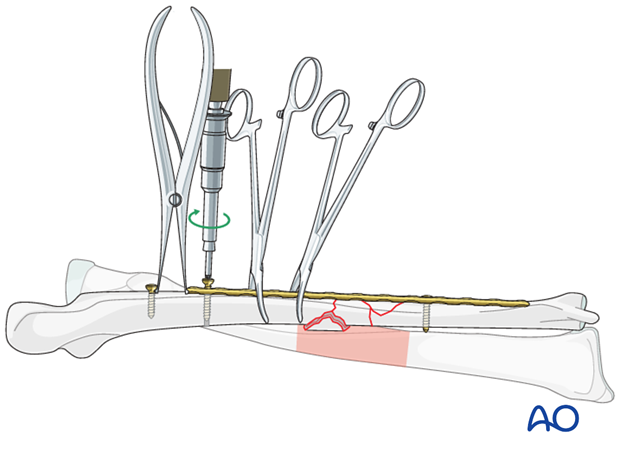

Use a laminar spreader between the independent screw and the end of the plate in order to distract the fracture, restoring length and axial alignment. The articulated tension device in distraction mode is an alternative to the laminar spreader.

A screw is inserted through the end hole of the plate adjacent to the laminar spreader.

One of the forceps is removed and the reduction is fine tuned as necessary. Once the reduction is completely satisfactory (clinically and radiographically), a second screw is added through the plate into the same main fragment. The laminar spreader, the remaining forceps and the independent screw can now be removed.

5. Reduction and preliminary fixation of the radius

Reduction

The second bone should be less difficult to reduce since the reduction of the first bone will often result in restoration of the length of the whole forearm. If successful reduction of the radius can not be achieved, re-assess the reduction of the ulna. If the ulnar reduction was not satisfactory, consider revising it, or dismantle the fixation and start with the radius as the first site of reduction and preliminary fixation.

Again, the aim of reduction is to restore length, and axial and rotational alignment.

It should be kept in mind that the radius is curved in both coronal and sagittal planes. Every attempt should be made (although not always possible in cases of severe comminution) to restore the normal radial curvature, in order to allow full range of pronation and supination.

Several reduction maneuvers can be useful:

- Manual traction, preliminary screw fixation of a plate to the proximal main fragment and a forceps on the distal main fragment

- Reduction by help of the plate and distraction using a laminar spreader and an independent screw (push-pull technique). The correct radial bow and rotation may be verified by making sure that the radial styloid is opposite the radial tuberosity in a supinated AP view.

Preliminary fixation of the radius

Note: Whereas on the ulna a forceps between the plate and the proximal ulna is safe, on the proximal radius, with an anterior approach, the use of a forceps can endanger the posterior interosseous nerve. For this reason, the plate is preliminarily fixed to the proximal fragment with a standard screw and is held to the distal fragment using a forceps.

As an angular stable plate is being used as an internal fixator, at least one of the screws in each main fragment needs to be a locking screw. Therefore, insert a locking screw into each main fragment near to the multifragmentary zone whilst carefully maintaining reduction.

The plate is fixed to the proximal main fragment using a standard screw though the end hole.

Check that rotational alignment is correct.

An independent screw is inserted into the distal main fragment a short distance (1 – 1.5 cm) beyond the distal end of the plate.

Use a laminar spreader between the independent screw and the end of the plate to distract the fracture, restoring length and axial alignment.

Once the reduction is completely satisfactory, additional screws are inserted.

As an angular stable plate is being used as an internal fixator, at least one of the screws in each main fragment needs to be a locking screw. Therefore, insert a locking screw into each main fragment near to the multifragmentary zone. The laminar spreader and its independent screw can now be removed.

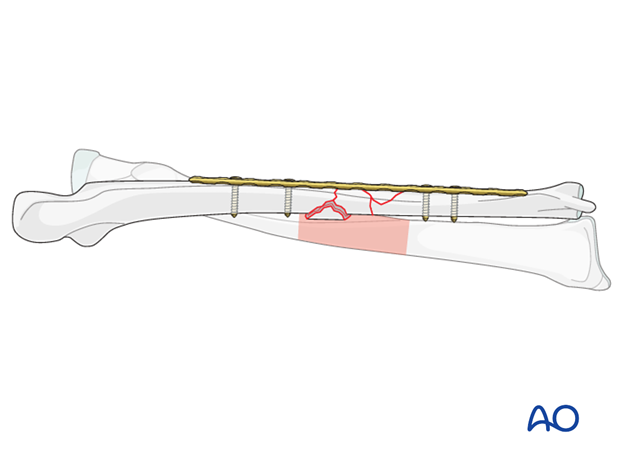

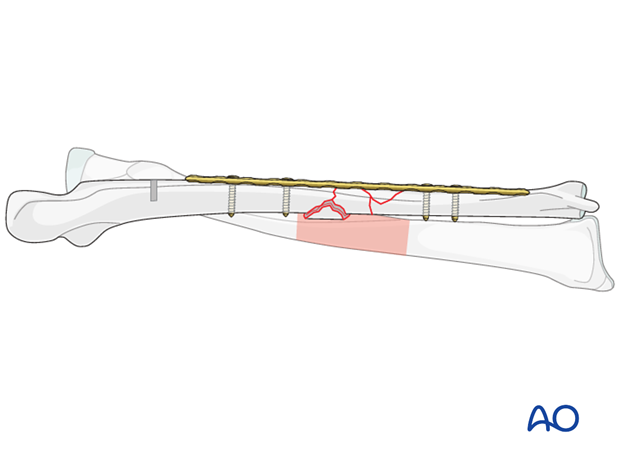

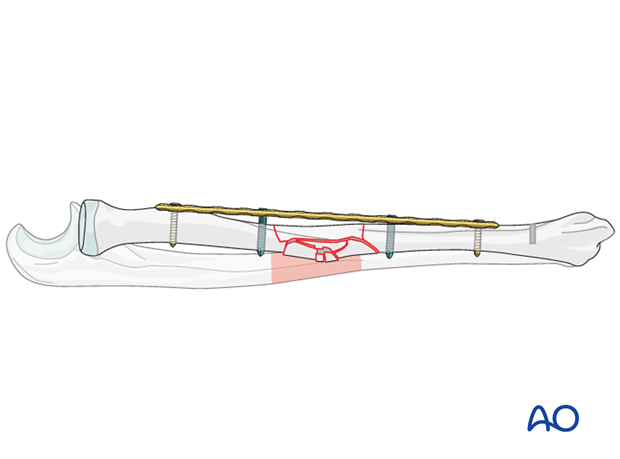

6. Definitive fixation of both bones

Assessment of overall forearm reduction

Before finally committing to a definitive fixation make the following checks:

- Gently examine the range of forearm rotation.

- Use image intensification 1) to check plate length and position, and 2) at each end of the forearm, to check the radioulnar relationships compared to the preoperative x-rays of the uninjured side.

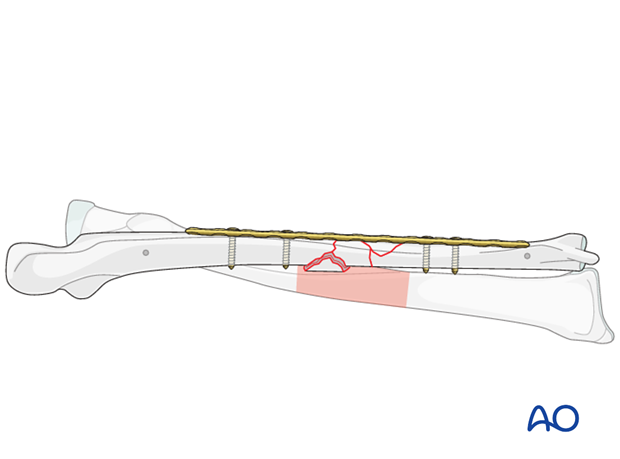

Now complete the ulnar fixation by inserting additional screws as necessary.

As a standard (non-locking) plate is usually used for the ulna, at least three bicortical screws should be inserted into each main fragment.

7. Final check of osteosynthesis

Check the completed osteosynthesis by image intensification. Make sure that the plates are at proper locations, the screws are of appropriate length and a desired reduction was achieved.

Again, check the range of motion in all directions. Because of the difficulty of perfect anatomical restoration of these complex fractures, it is advisable to check the congruity of the DRUJ radiographically by comparing it to the preoperative x-ray of the contralateral side. If residual displacement is revealed, the difficult decision then has to be made whether to attempt to revise the reductions and fixations, or to accept some residual DRUJ displacement.

8. Assessment of Distal Radioulnar Joint (DRUJ)

Before starting the operation the uninjured side should be tested as a reference for the injured side.

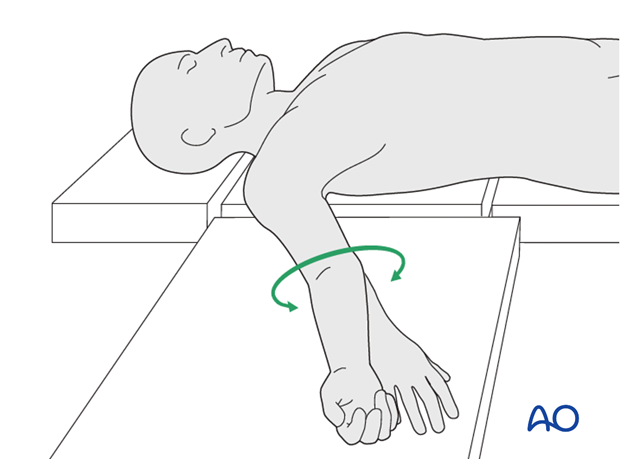

After fixation, the distal radioulnar joint should be assessed for forearm rotation, as well as for stability. The forearm should be rotated completely to make certain there is no anatomical block.

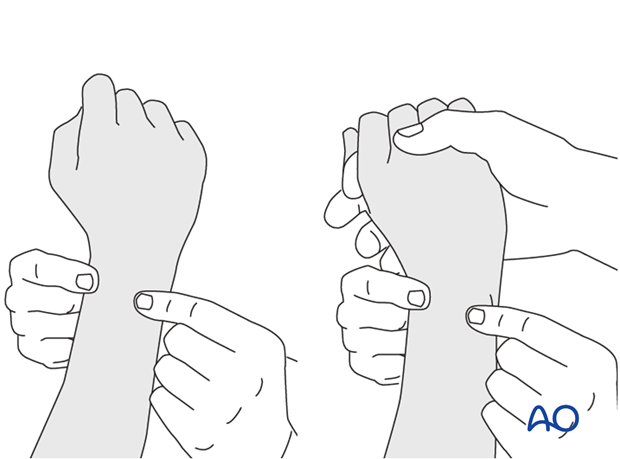

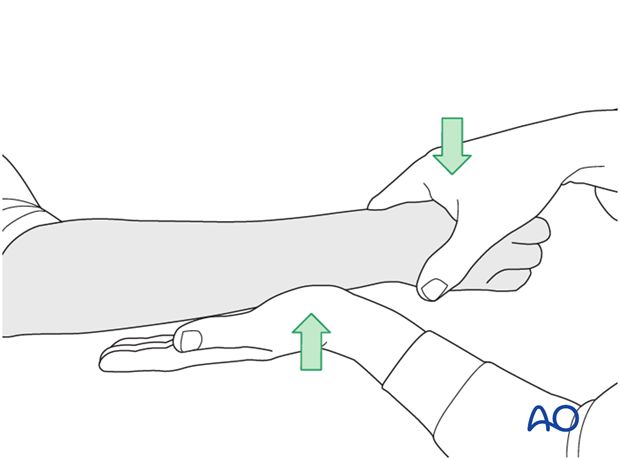

Method 1

The elbow is flexed 90° on the arm table and displacement in dorsal palmar direction is tested in a neutral rotation of the forearm with the wrist in neutral position.

This is repeated with the wrist in radial deviation, which stabilizes the DRUJ, if the ulnar collateral complex (TFCC) is not disrupted.

This is repeated with the wrist in full supination and full pronation.

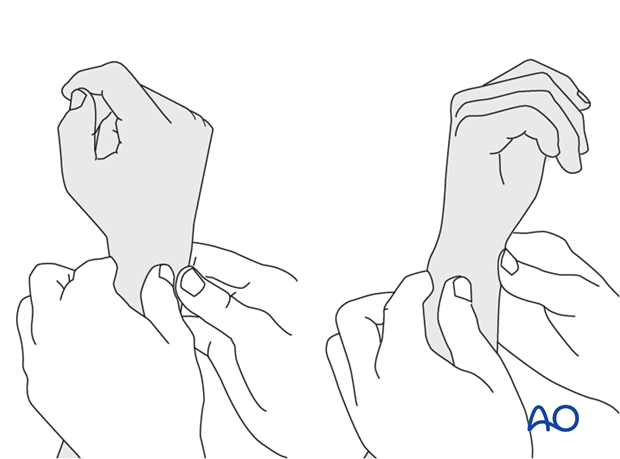

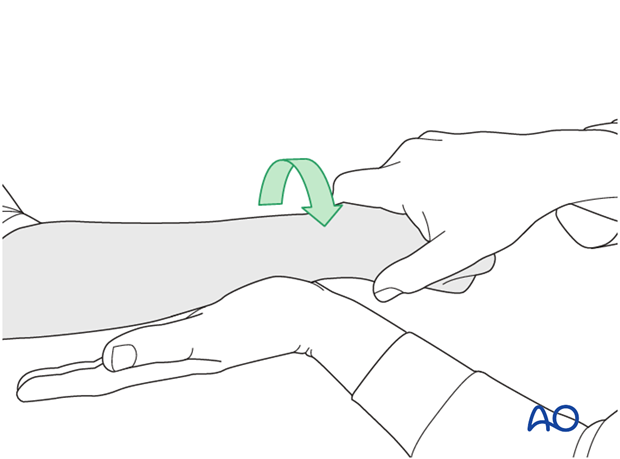

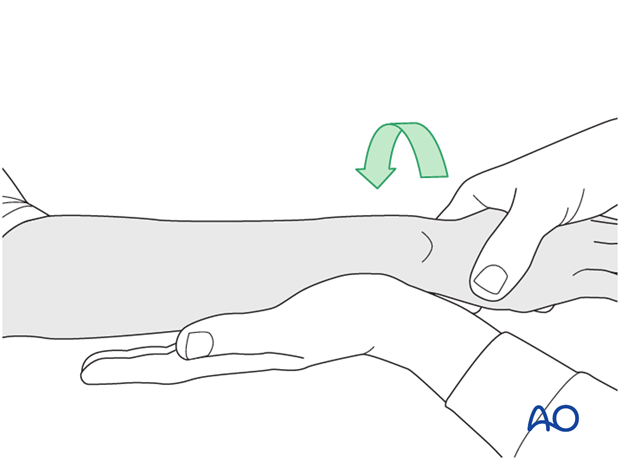

Method 2

In order to test the stability of the distal radioulnar joint, the ulna is compressed against the radius...

...while the forearm is passively put through full supination...

...and pronation.

If there is a palpable “clunk”, then instability of the distal radioulnar joint should be considered. This would be an indication for internal fixation of an ulnar styloid fracture at its base. If the fracture is at the tip of the ulnar styloid consider TFCC stabilization.

9. Wound closure

Subcutaneous tissue and skin should be closed by interrupted sutures. In certain instances, for example with marked forearm swelling, one of the wounds may have to be left open (usually the radial approach, as the ulna is subcutaneous). There are different techniques to overcome these difficulties (e.g., elastic closure, vacuum-assisted closure, petroleum jelly gauze, skin substitute, etc.)

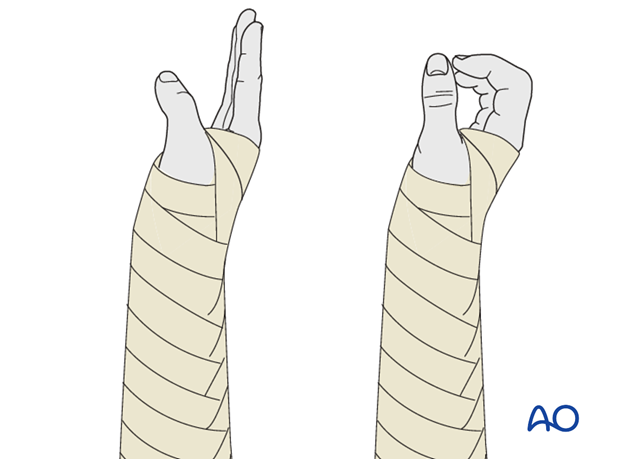

10. Postoperative treatment

Functional aftercare

Following stable fixation, postoperative treatment is usually functional.

Immobilization in a circular cast may compromise the range of motion later. However, since soft-tissue swelling, and edema are associated with these high-energy fractures, a temporary immobilization with a well-padded, bulky splint for 10-14 days is advised to allow adequate soft-tissue healing. During this period, elevation, gentle finger motion, active and passive, together with elbow flexion/extension and shoulder motion, can be started. The splint is then removed and active assisted range of motion exercises, including gentle forearm rotation, begin.

Lifting and resisted exercises are restricted until radiographic signs of healing appear. More intensive exercises, such as progressive resisted exercises can start at that time. Timing of return to sport will depend on the individual patient and the nature of the sport.

Follow-up

Close postoperative follow-up is required in these fractures. In those that have been treated by means of relative stability, secondary bone healing with callus formation is anticipated and early signs of delayed union should alert the surgeon to consider secondary interventions, such as bone grafting.

Follow-up x-rays should be obtained according to local protocol. X-rays to assess fracture position are usually taken at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after operation. Subsequent x-rays are usually taken to assess bony healing at appropriate intervals from 6-8 weeks, depending on the fracture configuration and potential for healing.

Implant removal

In forearm shaft fractures, the issue of implant removal is controversial. As the radius and ulna are not weightbearing bones, and as removal of plates can be a demanding procedure, implant removal is not indicated as a routine. There is a high risk of nerve damage associated with procedures to remove forearm plates.

Furthermore, as there is significant risk of refracture, most surgeons prefer not to remove plates from the forearm.

The general guidelines today are:

- removal only in symptomatic patients, possibly only on the ulna where the implants are subcutaneous

- removal no earlier than 2 years after osteosynthesis

- If both bones have been plated, sequential removal of implants with a least 6 months in between is recommended (risk of refracture).

References

- Bednar DA, Grandwilewski W (1992) Complications of forearm-plate removal. Can J Surg; 35(4):428-431.

- Langkamer VG, Ackroyd CE (1990) Removal of forearm plates. A review of the complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br; 72(4):601-604.

- Rosson JW, Shearer JR (1991) Refracture after the removal of plates from the forearm. An avoidable complication. J Bone Joint Surg; 73(3): 415-417.

- Heim D, Capo JT (2007) Forearm, shaft. Rüedi TP, Buckley RE, Moran CG (eds), AO Principles of Fracture Management, Vol. 2. Stuttgart New York: Thieme-Verlag, 643-656.