Olecranon screw traction

1. Introduction

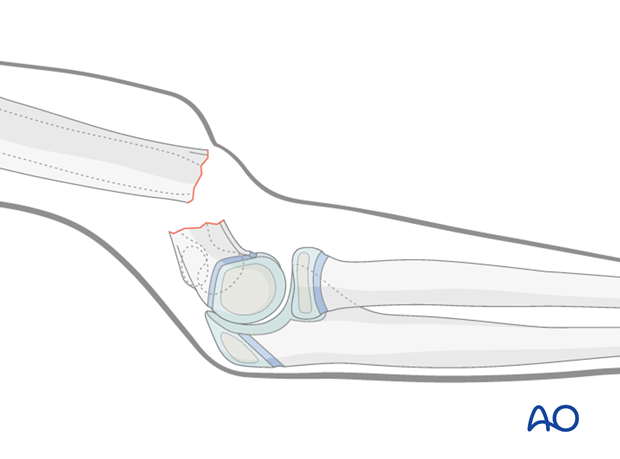

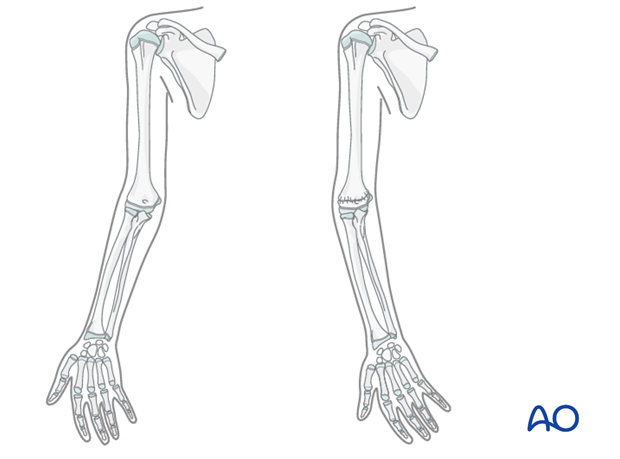

Olecranon screw traction is a useful technique for fractures that are not amenable to closed reduction and K-wire fixation.

In emerging healthcare settings, this may be a useful technique for severely displaced 13-M/3.1 III, 13-M/3.1 IV, 13-M/3.2 III and 13-M/3.2 IV fractures.

Indications for this technique are rare in settings where operating facilities, image intensification and the requisite specialist skills are readily available.

Manipulation of a displaced fracture in a child is painful and is very difficult with awake-sedation techniques. General anesthesia is therefore required for insertion of the olecranon screw and arrangement of the traction system.

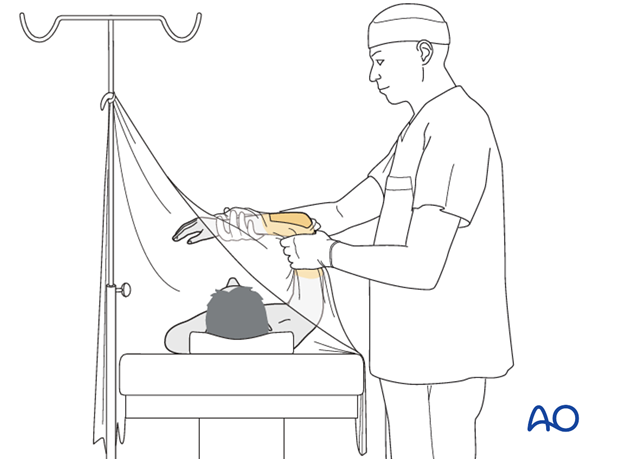

2. Patient preparation

The patient is positioned supine.

The skin is painted with antiseptic and draped with sterile towels exposing the elbow.

3. Fixation

Preparation

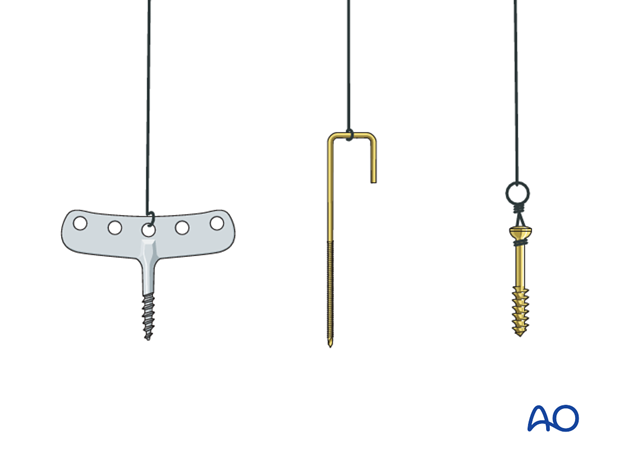

Equipment check list:

- Olecranon wing screw (if available), or a bent Schanz screw (3.0/4.0 mm), or large cancellous screw

- Sterile skin preparation

- Drapes

- # 15 blade

- Hand drill or T-handle chuck

Note: A large cancellous screw with a short thread can be inserted to the thread depth and then a traction loop fashioned around the neck of the screw for attachment of the cord.

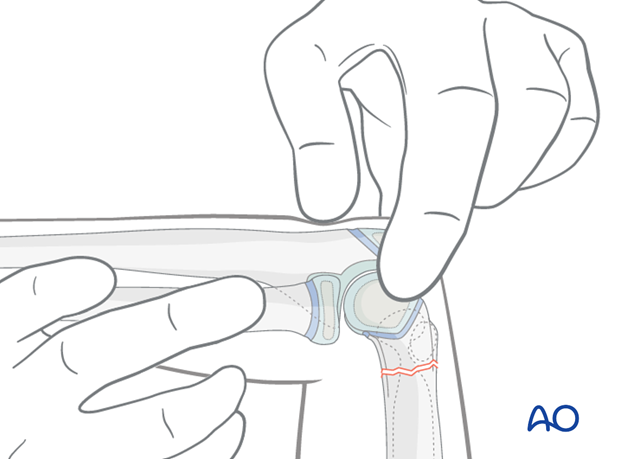

The following structures are identified and can be marked with a skin marker pen:

- Tip of the olecranon

- Subcutaneous surface of the proximal ulna

- Medial humeral epicondyle

- Lateral humeral epicondyle

- Radial head

Note: In a swollen elbow the anatomical landmarks may be difficult to palpate and x-ray control of the proposed entry track may be used.

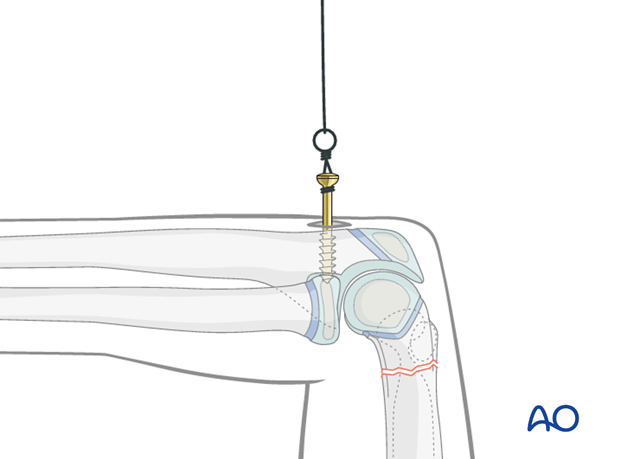

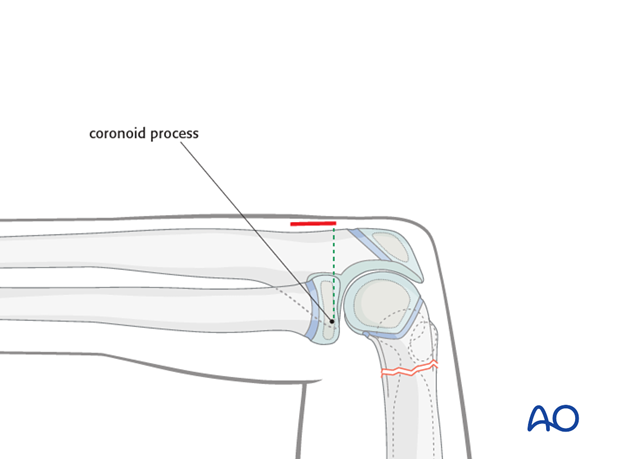

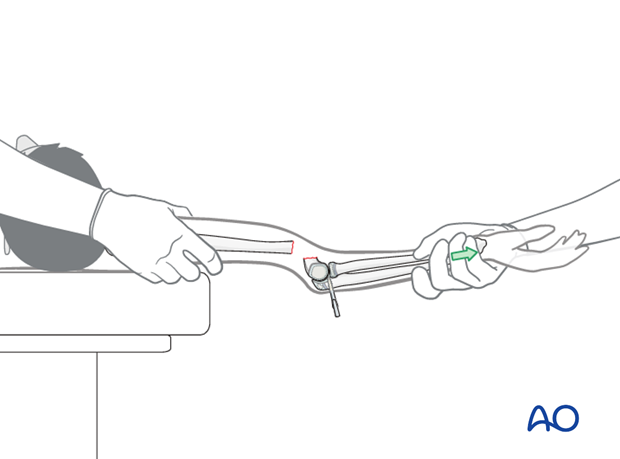

A stab incision is made directly over the subcutaneous proximal ulna directly opposite the tip of the coronoid process. Palpating the radial head may help to identify the level of the coronoid process.

Insertion of screw

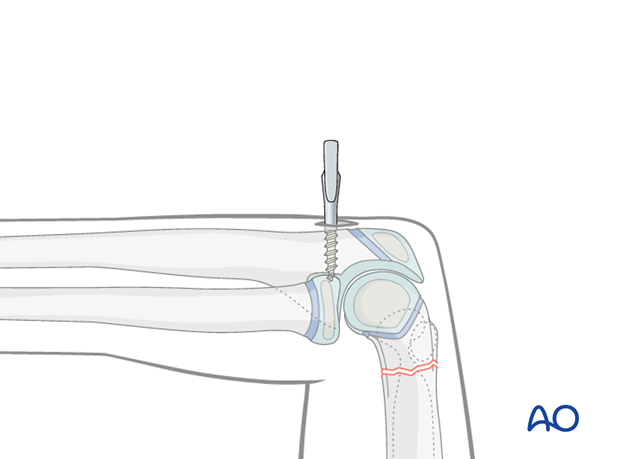

The tip of the olecranon screw, or self-drilling Schanz screw, is placed directly onto the bone.

The screw is advanced by hand until the resistance of the anterior cortex is felt. In the case of a cancellous screw, the most proximal thread turn should not be buried underneath the skin.

If an olecranon wing screw is used, the screw is turned until the wings are oriented directly medial to lateral.

4. Reduction

Soft tissue reduction

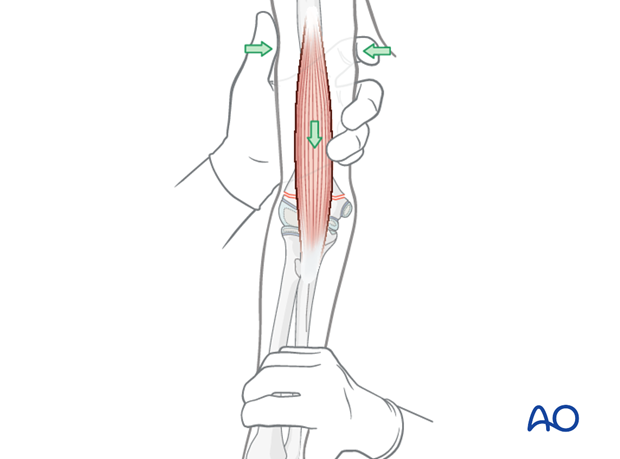

As a preliminary reduction of the fracture, the soft tissue shortening and soft tissue reduction need to be addressed.

A careful inspection of the soft tissues is performed to look for:

- The degree of swelling

- The position of the humeral shaft relative to the muscles (ie, buttonholed anteriorly)

- Tethering of the dermis over the humeral shaft (pucker sign)

The goal of the reduction maneuver is to disengage the humeral shaft from the muscles and skin, allowing accurate reduction of the bony fragments.

A palpable soft tissue reduction will often be felt during the application of traction.

The pucker sign, if present, will visibly reduce with successful traction.

Pearl: If the muscle is stuck despite traction, a milking maneuver can be attempted.

Starting proximally at the humeral head, the brachialis muscle is gently and repeatedly "milked" distally and anteriorly in order to liberate the soft tissues from around the protruding proximal fragment.

5. Traction

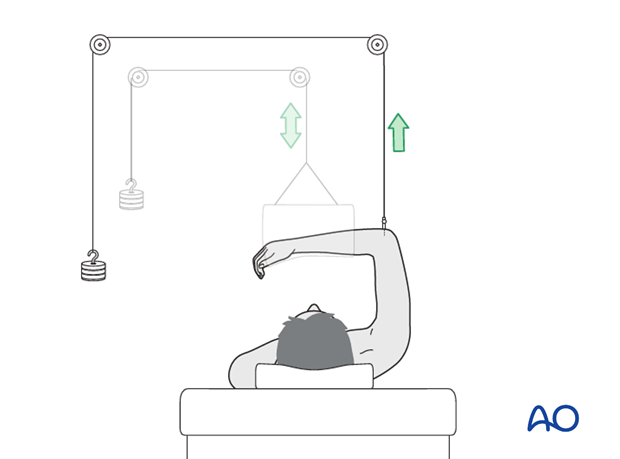

Once the soft tissue reduction is completed, positional control will be achieved during the traction phase.

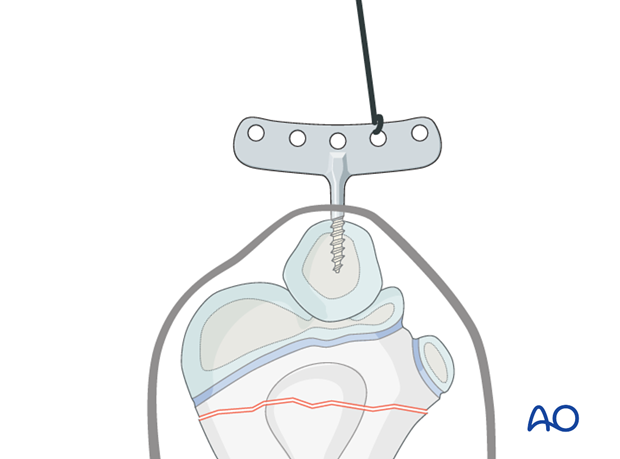

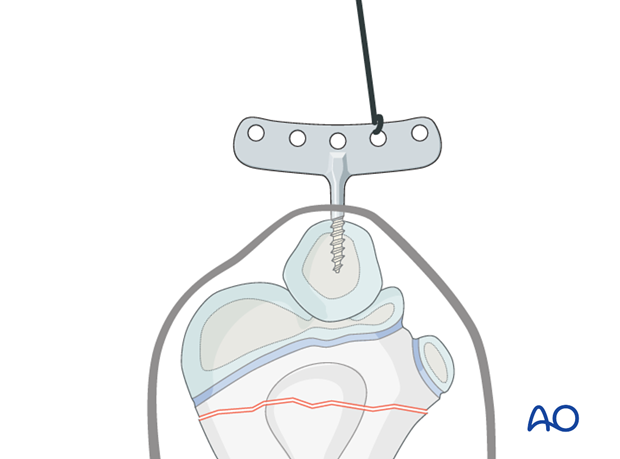

Primary traction is applied directly to the olecranon screw starting with 2.5 kg until the scapula is just lifted off the bed.

A cloth sling can be used to support the forearm for reasons of comfort, but is rarely necessary.

If necessary a valgus force can be produced by moving the attachment point of the traction rope medially on the olecranon implant or Schanz pin. This is useful in preventing a varus malunion.

It is unusual to position the cord on the lateral side to produce a varus force, as this may result in varus malunion.

Healing in neutral or in a small amount of valgus is cosmetically acceptable.

In practice overhead olecranon traction results in a pronated forearm, which tends to tilt the fragment out of varus malposition.

As swelling reduces and comfort improves, the position can be adjusted as needed during the first 4-5 days of traction.

Alignment of the fracture can be assessed by visual inspection, and portable plain x-rays.

Modest amounts of residual translation or rotation still allow good cosmetic and functional results.

A varus position should be avoided, as this can be a common source of poor cosmesis and patient's and parents' dissatisfaction.

6. Immobilization

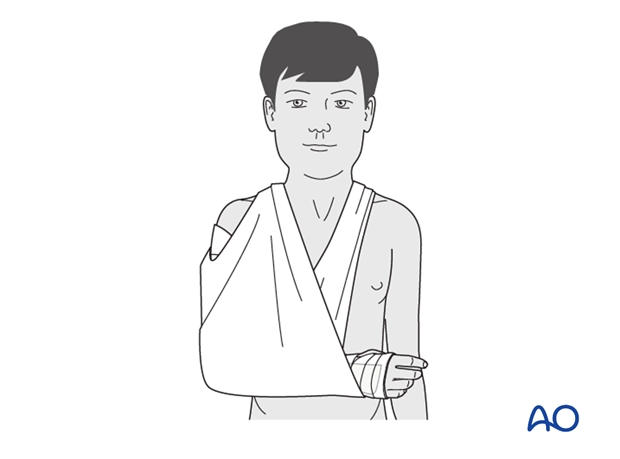

After 10–14 days, when nontender fracture callus is palpable, the traction screw is removed, usually under light sedation.

The injured arm is then placed in a splint or cast with the elbow at 90° flexion for two more weeks.

Some surgeons will use a simple collar and cuff at this stage, especially in the younger child.

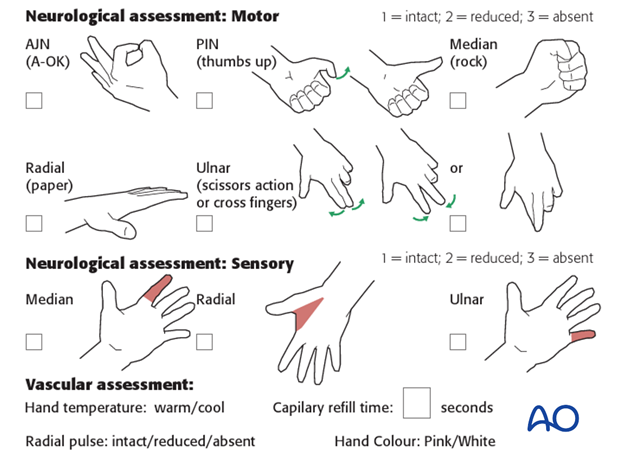

Note: In any case of elbow immobilization by plaster cast, careful observation of the neurovascular situation is essential both in the hospital and at home.

7. Aftercare

Supracondylar humeral fractures heal rapidly and often within 3–5 weeks.

Analgesia, including ibuprofen and paracetamol, should be administered regularly.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a possible early postoperative complication that may be difficult to diagnose in younger children.

The child should be examined frequently, to ensure finger range of motion is comfortable and adequate.

Neurological and vascular examination should also be performed.

Increasing pain, decreasing range of finger motion, or deteriorating neurovascular signs should prompt consideration of compartment syndrome.

See also the additional material on postoperative infections.

Discharge care

When the child is discharged from the hospital, the parent/caregiver should be taught how to assess the limb.

They should also be advised to return if there is increased pain or decreased range of finger motion.

It is important to provide parents with the following additional information:

- The warning signs of compartment syndrome, circulatory problems and neurological deterioration

- Hospital telephone number

- Information brochure

Follow-up x-rays

X-rays on traction may be taken at one week following injury to assess fracture position. Further x-rays may be necessary at three weeks to assess fracture healing. This should be performed after the splint has been removed.

Removal of cast or splint

Splints or casts are usually removed within 3 weeks of the injury.

Recovery of motion

As symptoms recover, the child should be encouraged to remove the sling and begin active movements of the elbow.

The majority of elbow motion is recovered rapidly, usually within two months of splint removal. The older child may take a little longer.

Once the child is comfortable, with a nearly complete range of motion, he/she may resume noncontact sports incrementally. Resumption of unrestricted physical activity is a matter of judgment for the treating surgeon.