ORIF - Compression plating

1. Principles

General considerations

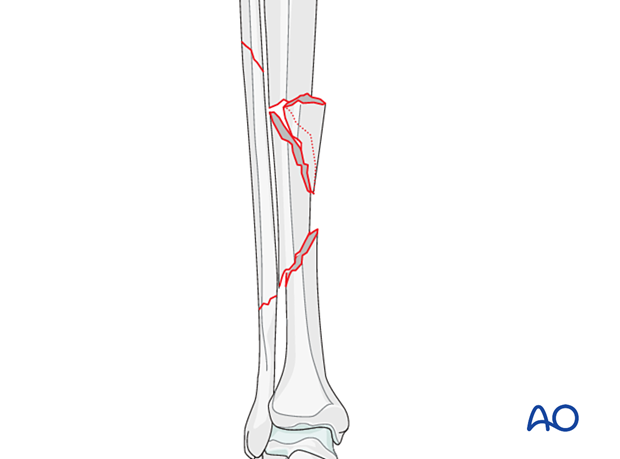

Intact segmental fractures are high-energy injuries and may have significant closed or open soft-tissue damage. Either or both fracture planes may have simple patterns, for which absolute stability is beneficial.

While compression plating may be appropriate for the transverse fracture components, significant fragmentation at any part of an intact segmental fracture should suggest fixation with relative stability, using either an intramedullary nail or bridge plating.

Utmost care is necessary to protect soft tissues attached to intermediate fragments, so as to avoid devascularization.

An appropriate surgical strategy is sequential with stepwise reduction of the fracture planes, as illustrated. The idea is to reduce and stabilize one fracture line at a time.

The following fracture example illustrates several possible options for compression plating of less comminuted segmental fractures. Treatment for any segmental tibia fracture must be planned and executed according to its specific injury patterns and should follow general principles.

Indications

Compression plating is typically used to obtain absolute stability for transverse or short oblique fracture patterns. In this case secure fixation of the wedge fragment at the proximal fracture line will convert this to a transverse fracture, suitable for axial compression.

2. Patient preparation and approaches

Patient preparation

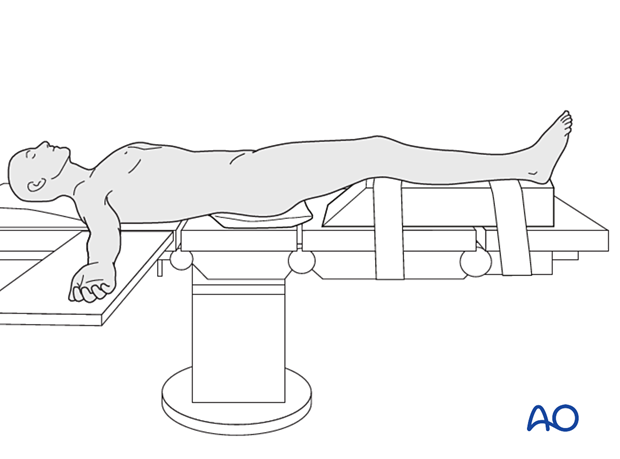

The patient is placed in a supine position on a radiolucent table or a standard operating table with a radiolucent extension. A pad is placed underneath the buttock to prevent external rotation.

A large foam bolster or cushion is placed under the affected leg to raise it above the opposite leg and facilitate lateral C-arm images.

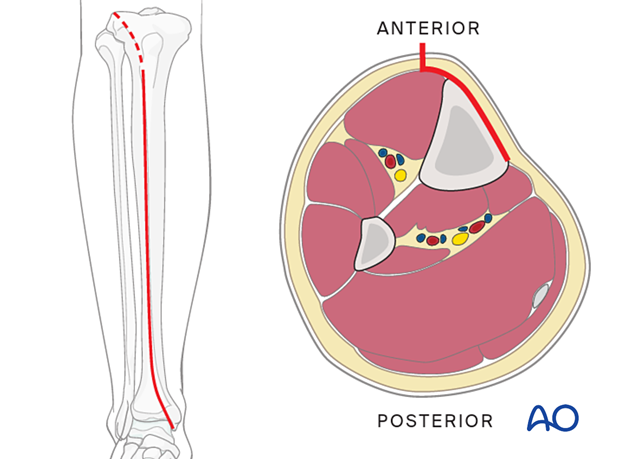

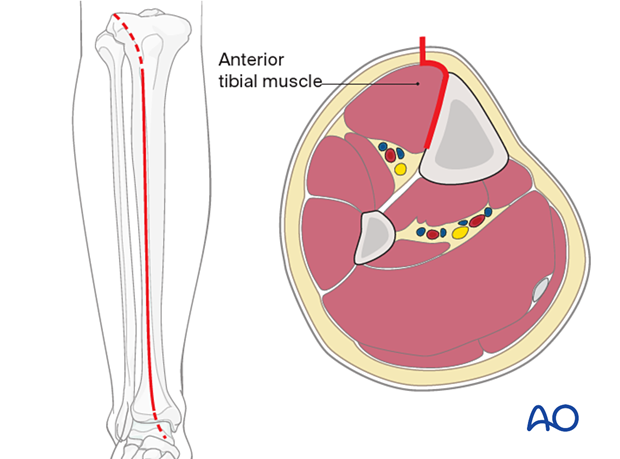

Anteromedial approach

An anteromedial approach is preferred if the soft-tissue envelope allows. The advantage of this approach is that it removes no muscle from the fracture fragments. Also, the medial surface of the tibia is normally flat, and conventional plates can be contoured to fit it or precontoured plates used with minimal or no modification.

Anterolateral approach

The anterolateral approach should be chosen if the soft tissues do not allow for an anteromedial approach. It is difficult to use this approach distally due to soft-tissue interference and the challenge of contouring the plate along the lateral aspect of the tibia.

3. Reduction

Reduction principles

The key to all fracture reduction is restoring axial length.

Ways of gaining length are:

- Manual traction

- Distractor/external fixator

- Reduction forceps

- Using the plate as a reduction tool

- Articulated tension device (ATD)

- Push-pull screws

If any shortening is present, distraction should be applied and maintained before fracture consolidation occurs. Otherwise, callus and vascular soft tissues will need to be released from bone fragments to permit reduction. This may require provisional external fixation. Even if the delay before reduction and fixation is short, progressive intraoperative lengthening is easier and less traumatic if aids for distraction are routinely employed.

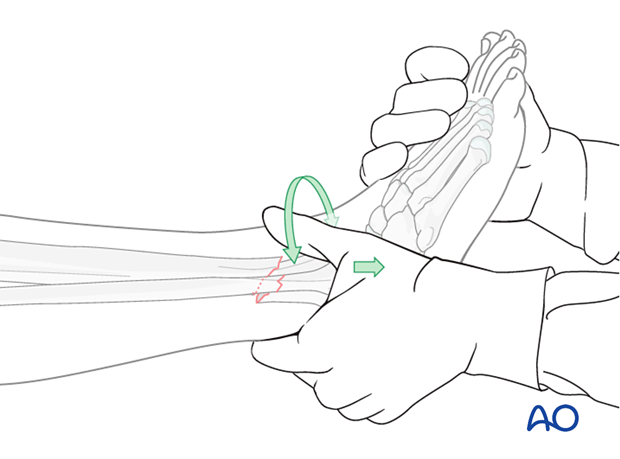

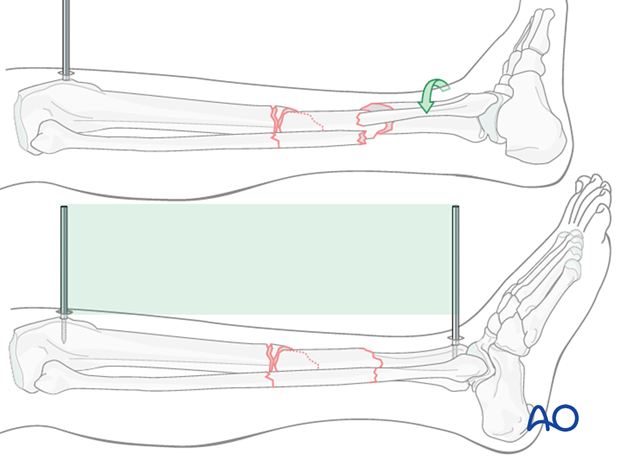

Manual traction

Apply longitudinal traction to the foot.

After correct length and axial alignment have been achieved, evaluate and correct the rotational deformity. One should determine the correct rotation from the uninjured extremity preoperatively.

Manual traction can be effective in fresh fractures but may be ineffective in fractures with soft-tissue contractures, significant shortening, or early fracture healing.

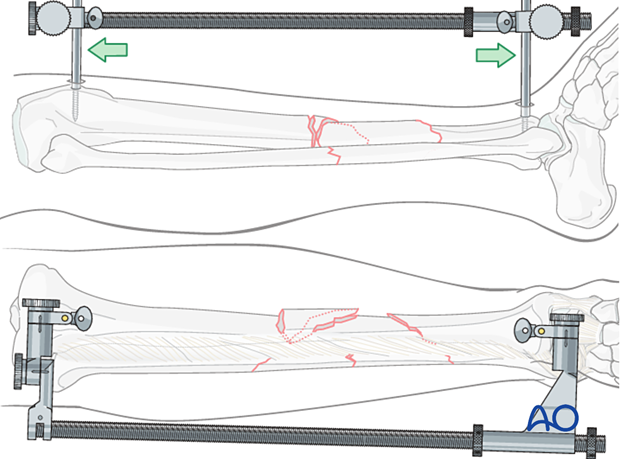

Large distractor or external fixator

A large distractor is very helpful for reduction. Place Schanz pins in the proximal and distal fragments. Distraction is applied across these pins by turning the nut on the threaded rod.

If the plate is to be placed medially, then the distractor should be placed anteriorly.

Rotational alignment must be considered during the application of the distractor or external fixator.

These are uniplanar devices. Once applied, rotation of the fracture fragments cannot be adjusted significantly. Thus, the pins should be placed so that when they are in the same plane, malrotation is corrected, and the fracture is reduced.

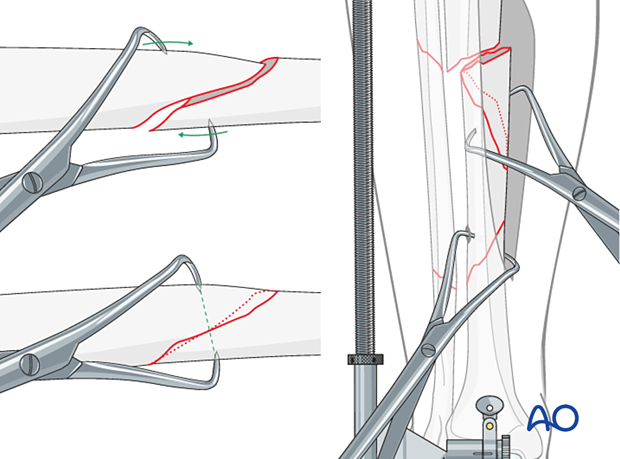

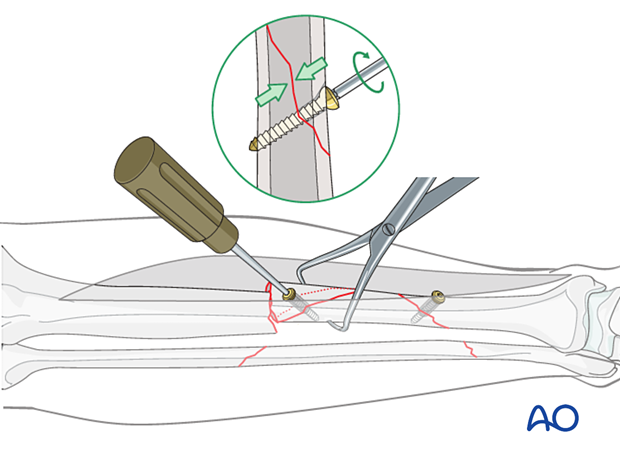

Reduction forceps

Reduction of wedge fragments and oblique fracture lines can be done with pointed reduction forceps.

Make every effort to preserve soft-tissue attachments (blood supply) to the fracture fragments.

Placement of the reduction forceps is key. Each point must be placed in anticipation of where it will be with the fracture reduced once length is restored. These forceps will often be placed almost along the line of an ideal lag screw. In the left-hand close-up view, note how interfragmentary fracture reduction can be achieved by twisting (clockwise, as illustrated) properly applied pointed reduction forceps. This produces translation of the fragments along the fracture plane.

Once reduced, the individual fractures can be either provisionally stabilized with reduction forceps or definitively fixed with a lag screw.

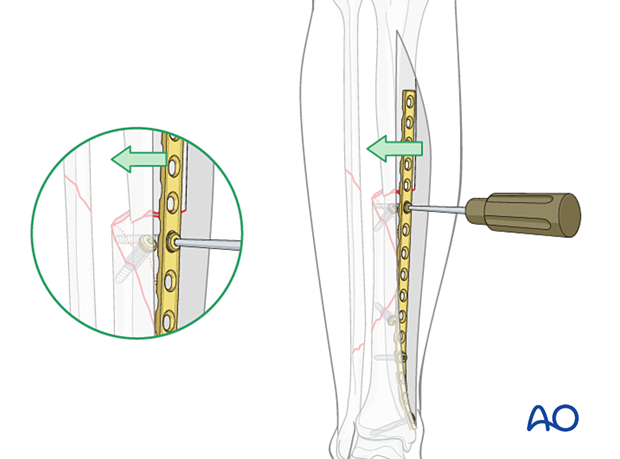

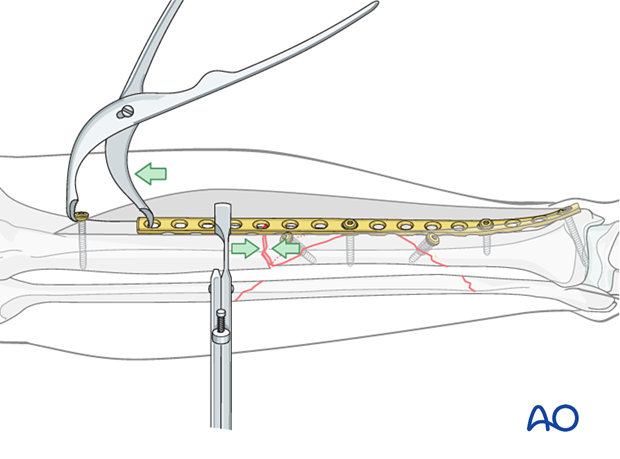

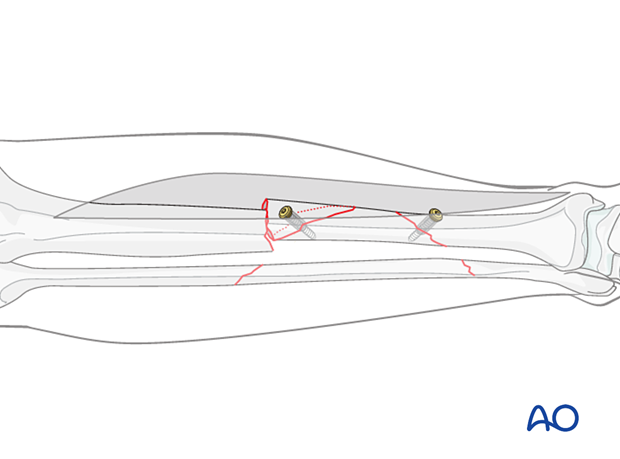

Plate as reduction tool

Translation can be corrected by applying a well-contoured plate. With the plate positioned against one fracture fragment, the adjacent fragment is pulled to the plate with a well-placed cortical screw.

The plate must be shaped to fit the bony surface for this technique to be effective.

Remember to correct deformity in both AP and lateral planes. A good reduction in the AP plane, as shown here, does not necessarily mean that the lateral plane is correct.

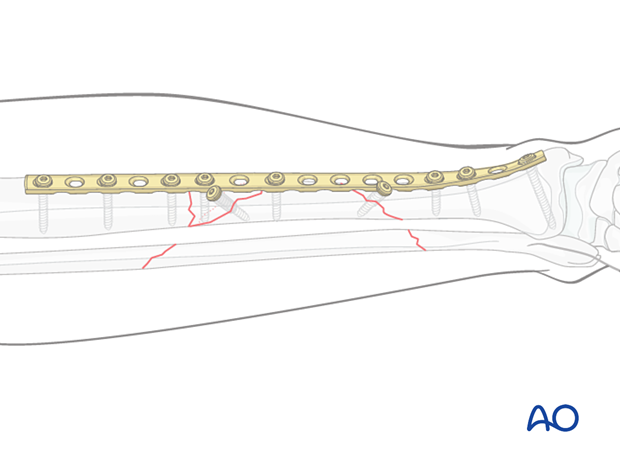

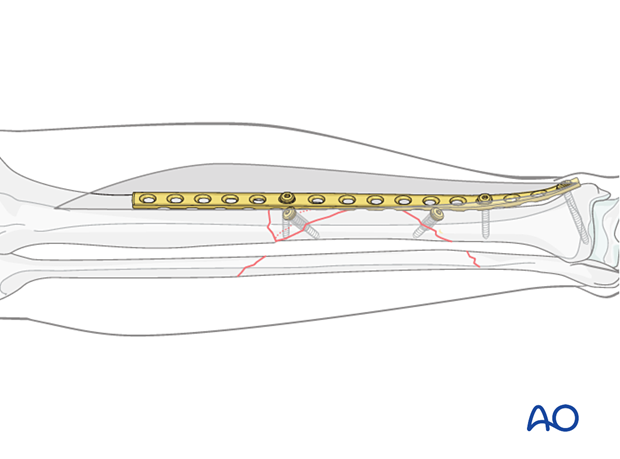

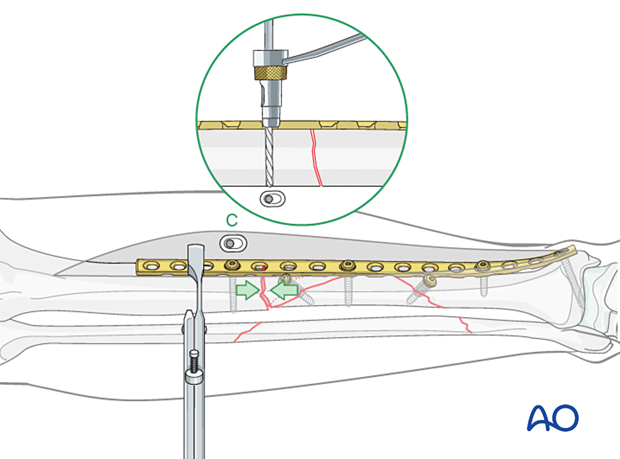

This figure illustrates a long, properly contoured plate applied to the distal and intermediate fragments. Lag screws compress both the distal fracture, and the wedge fragment. The proximal end of the plate is now ready to be attached to the proximal tibial fragment.

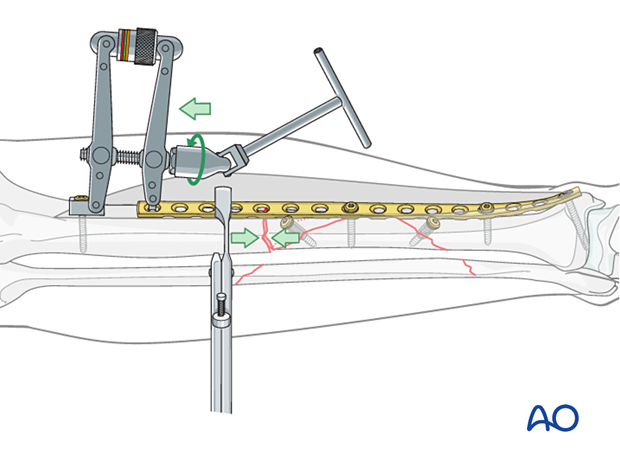

Articulated tension device (ATD)

A lag screw is not suitable for a transverse fracture. In the illustration, an articulated tension device (ATD) is used to compress the transverse fracture before screws are placed through the plate.

Note that the distal end of the wedge fragment has been fixed with a lag screw before axial compression is applied. A bicortical screw should be attached through the plate into the intermediate fragment for additional stability before compressing the proximal fracture, as shown in this illustration.

Push-pull screw

Alternatively, a Verbrugge clamp in combination with a push-pull screw can be used to compress across the transverse fracture.

4. Plate selection and preparation

Choice of plate

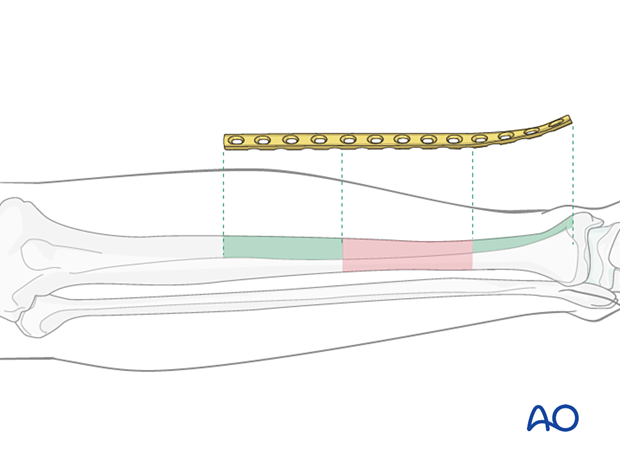

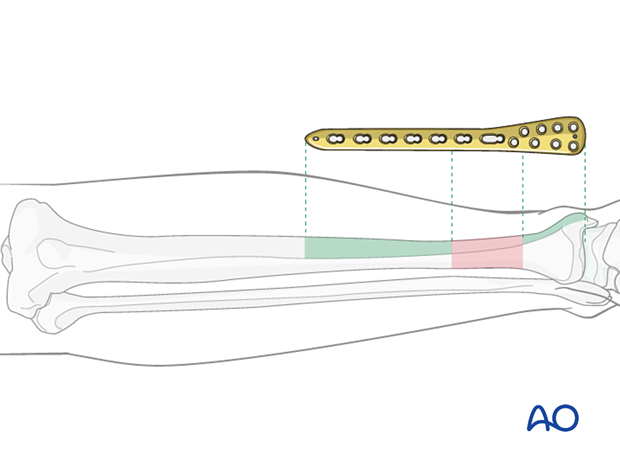

Plate length is based upon symmetry above and below the fracture zone. In the case of a segmental fracture, the fracture zone includes all fracture lines. In C-type fractures, at least 3–4 screw holes on either side of the fracture zone are necessary. Another guideline, when fracture location permits, is that the plate should be roughly three times the length of the fracture zone.

When the fracture zone is very distal or proximal, there may not be enough room for symmetric plate length in the segment nearest the articular surface. In this situation, a plate with multiple hole options in the metaphysis is chosen to improve fixation in the short periarticular segment.

A locking plate may be indicated if the bone quality is poor or when the fracture extends into softer metaphyseal bone.

Traditionally a 4.5 mm plate has been advised for the tibial shaft. Advantages include increased plate thickness and larger screw size for added strength. These plates are difficult to contour and may be too prominent.

A 3.5 mm plate offers improved contourability and multiple screw options in metaphyseal (end-segment) zones. As these plates are thinner, they are less stiff than the large fragment plates.

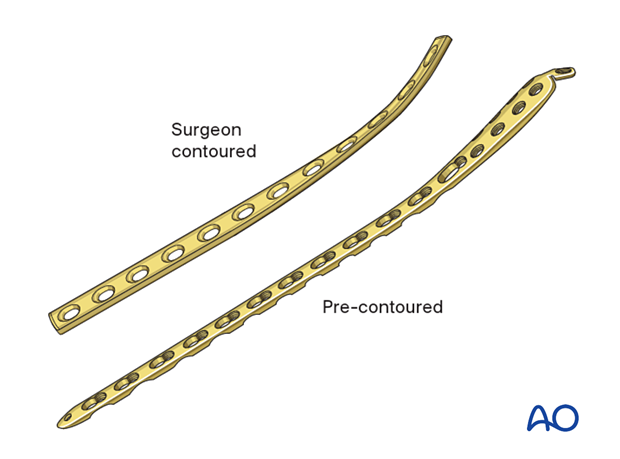

Another consideration is the choice between an anatomically precontoured plate or one which the surgeon contours. For plates that need to be contoured, the following steps must be employed.

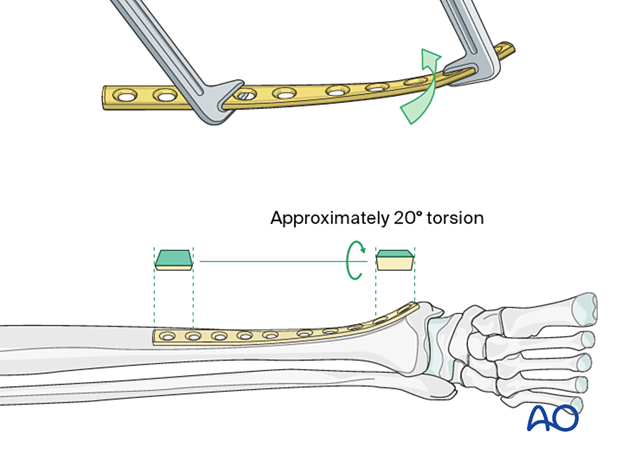

Twisting the plate

The anteromedial surface of the tibial shaft twists internally approximately 20° as it approaches the medial malleolus.

The first step of plate contouring is to twist the plate so it matches the tibial surface upon which it will lie.

If the plate is bent before it is twisted, the process of twisting will alter the bend that has been created.

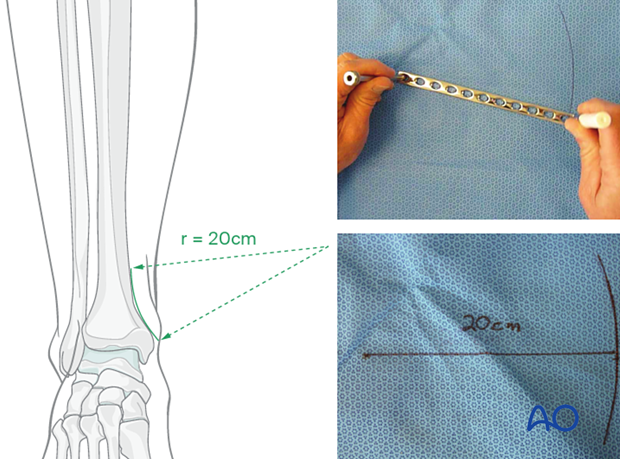

Matching the curvature

Depending upon the plate location, more or less bending of the plate will be required to match the contour of the intact (or reduced) bone. Much of the medial tibial shaft is quite straight so little bending is required. The distal medial surface has a significant concavity, with a typical radius of curvature of 20 cm, as illustrated.

A 20 cm radius can be drawn on a sterile drape and used as a template for plates to be used in this location.

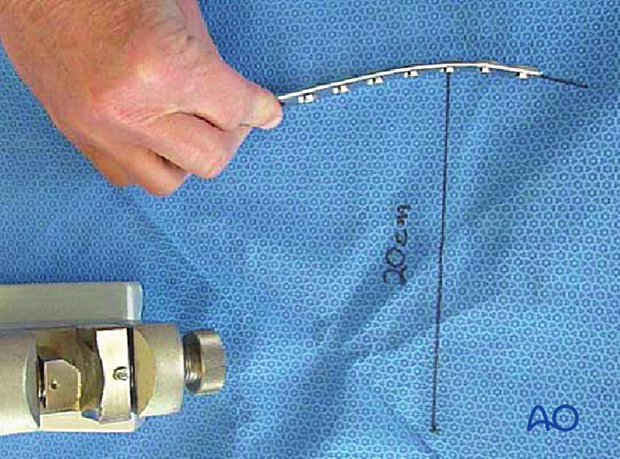

Bending the plate

The plate can be bent with bending irons alone, but bending with a bending press is preferable because it gives more control.

In either case, the bending is done in small steps to produce a smooth contour. Contouring only takes place over the distal 10–12 cm of the plate. When finished, the plate should match the 20 cm radius of curvature.

5. Plate application

Lag screw insertion

Once the fracture is reduced, a lag screw can be used to secure the final reduction.

This allows removal of provisional fixation, making it easier to apply the plate for definitive fixation.

Lag screws should not be allowed to interfere with the plate. If possible, place them outside the plate’s footprint.

If screws must be underneath the plate, they should be countersunk so they are flush with the bone surface. This is easier if smaller diameter screws are used.

Alternatively, the plate can be applied before interfragmentary lag screws are placed through it, and across a sufficiently oblique fracture plane. Remember that axial compression by loading the plate, usually with an ATD or a push-pull screw, is necessary to achieve absolute stability for more transverse fracture planes. A plate that simply bridges such a fracture, without some form of interfragmentary compression, produces a high-strain environment that interferes with direct bone healing.

Axial compression with eccentric screw

Now, with the fracture reduced and the plate properly positioned, drill eccentrically for the first screw in the proximal segment. Insert the eccentrically positioned screw fully to compress the transverse fracture site.

For oblique fractures, remember to use plate compression “into the axilla” of plate and bone. Only using an eccentric compression screw may not produce sufficient compression, unless a nearly perfect reduction is present before the screw is tightened. Many surgeons therefore prefer to use a device external to the plate (such as an ATD) to compress more complex fractures like the illustrated C2 pattern.

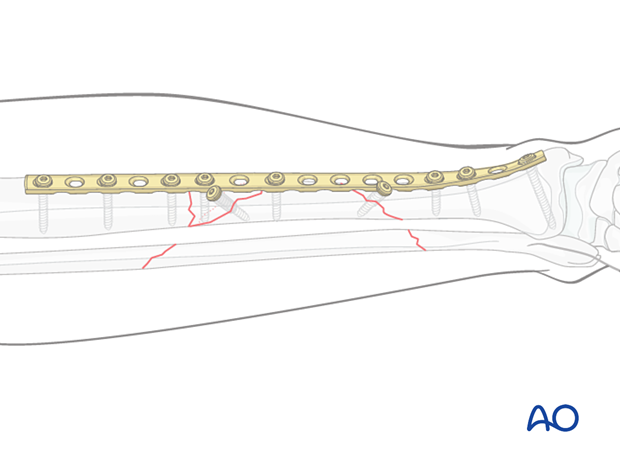

Insertion of remaining screws

The remaining screws are placed through the plate.

Remember that it is not necessary to fill every hole in the plate, particularly in the diaphysis.

6. Aftercare

Perioperative antibiotics may be discontinued before 24 hours.

Attention is given to:

- Pain control

- Mobilization without early weight bearing

- Leg elevation in the presence of swelling

- Thromboembolic prophylaxis

- Early recognition of complications

Soft-tissue protection

A brief period of splintage may be beneficial for protection of the soft tissues but should last no longer than 1–2 weeks. Thereafter, mobilization of the ankle and subtalar joints should be encouraged.

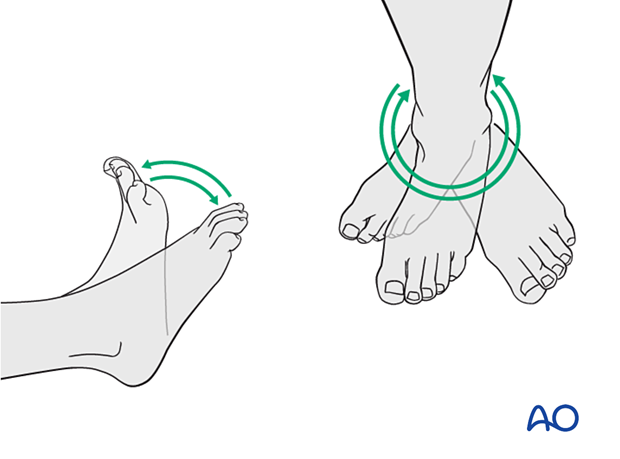

Mobilization

Active, active assisted, and passive motion of all joints (hip, knee, ankle, toes) may begin as soon as the patient is comfortable. Attempt to preserve passive dorsiflexion range of motion.

Weight bearing

For fractures treated with plating techniques, limited weight bearing (15 kg maximum), with crutches, may begin as tolerated, but full weight bearing should be avoided until fracture healing is more advanced (8–12 weeks).

For fractures treated with intramedullary nailing, weight bearing as tolerated, with crutches, may begin immediately.

Follow-up

Follow-up is recommended after 2, 6, and 12 weeks and every 6–12 weeks thereafter until radiographic healing and function are established. Weight bearing can be progressed after 6–8 weeks when x-rays have indicated that the fracture has shown signs of progressive healing.

Implant removal

Implant removal may be necessary in cases of soft-tissue irritation caused by the implants. The best time for implant removal is after complete bone remodeling, usually at least 12 months after surgery. This is to reduce the risk of refracture.