Classifications of wound infection

1. Classifications of wound infection

Introduction

A variety of factors influence the prognosis of fracture wound infections. Unlike hematogenous osteomyelitis, a fracture wound begins with damaged soft tissue and bone, and thus locally reduced resistance to infection. There may also be necrotic bone, and perhaps foreign material, where bacteria are protected from host defenses and blood-borne antibiotics, often sheltering in biofilms.

Factors to consider in classifying infections are:

- Duration of infection

- Anatomical area of bony involvement

- Host resistance (systemic and/or local)

- Status of fixation

- Fracture healing status

- Bacteriology

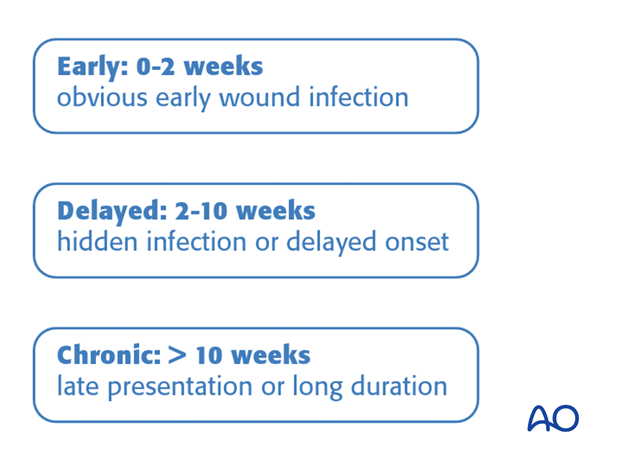

Classification according to chronology of onset of infection

Onset of fracture-site infection can be related to the time elapsed since the fracture occurred. However, the actual onset of infection may be delayed, beginning some time after the injury. This is relevant since progressive infection leads to additional tissue damage, and spread of infection outward from the original infected site. It is sometimes difficult to know exactly when an infection begins. When it is first diagnosed sometime after the original injury, a careful history from the patient and/or review of laboratory data may suggest a shorter duration of active infection.

Remembering the above, it may still be helpful to consider the major features of infection classified according to time after injury.

Early infection

Early infections generally occur less than 2 weeks after surgery. Their clinical signs are:

- increasing local pain

- redness

- swelling

- wound drainage

- disturbed wound healing

- fever

Typically, infecting organisms are highly virulent (staphylococcus aureus, Gram negative bacilli). Clostridial infections (gas gangrene, or tetanus) are other significant early infections.

Early infections need prompt surgical treatment for debridement as well as appropriate adjunctive antibiotics.

Such infections are not “superficial”, as the entire fracture wound is almost always involved. Only surgical exploration allows comprehensive assessment and care.

In addition, tissue samples taken at this time offer the chance to culture organisms hidden in biofilms.

Surgeon neglect allows the infection to progress to a point where relatively simple debridement may not succeed.

When symptoms have been present for less than 2 weeks, and internal fixation implants still provide absolute stability, it may be possible, after thorough debridement and with appropriate antibiotics, to retain them until the fracture is healed. Should the infection fail to resolve rapidly, repeated debridement, including implant removal with alternative fixation will be necessary.

Delayed presentation of infection

- Infection may not be seen until several weeks after surgery.

- More aggressive treatment is usually necessary.

Click here to read more about delayed presentation of infection.

Chronic infection

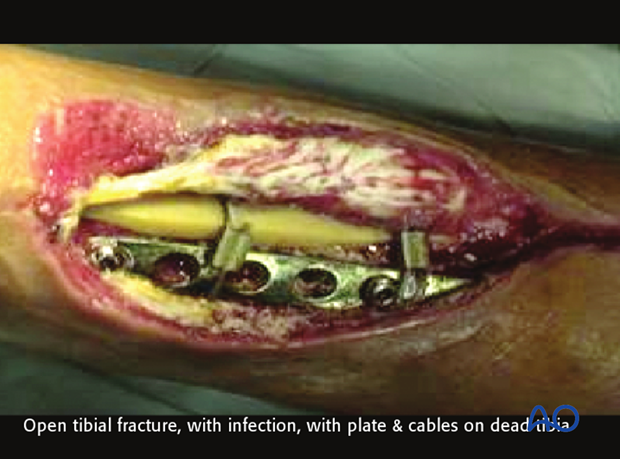

An infection which has been present in a fracture wound for more than several weeks is a serious and challenging problem. Typically, such wounds have failed previous treatment attempts, or have been neglected.

If internal fixation devices are present, they almost definitively have microorganisms within a layer of adherent slime. These chronic fracture site infections also include dead bone and soft tissue. The necrotic tissue may be localized, or diffuse. Without its complete removal, there is essentially no hope of controlling the infection. Furthermore, fracture healing will not occur until the infection is controlled and tissue viability restored.

Treatment requires radical debridement, often requiring several operations, and fracture stabilization, almost always with external fixation. Extensive bone removal may result in a segmental defect, or loss of an involved joint. So much tissue may have to be removed that reconstruction becomes less successful than amputation. Failure to control infection may also lead to loss of limb.

Recurrent osteomyelitis

- Posttraumatic osteomyelitis may recur, sometimes years after the original infection appears to have resolved.

- Treatment depends upon:

- fracture healing

- implants

- sequestra

Click here to read more about recurrent osteomyelitis.

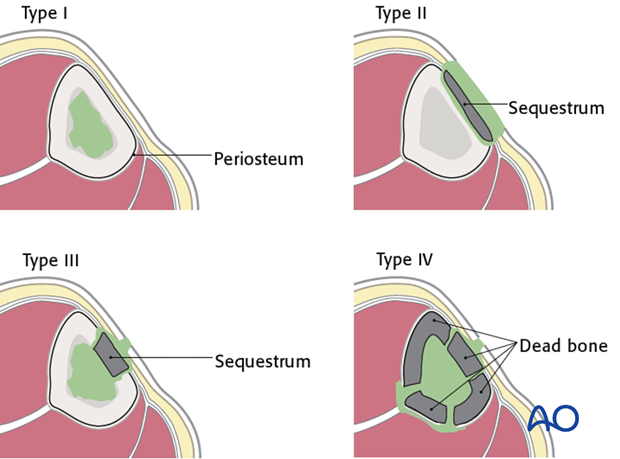

Cierny’s anatomical classification

The anatomical classification of osteomyelitis (see diagram) is important for understanding and localizing the infection.

- Type I (medullary osteomyelitis) diffusely involves the intramedullary cavity, essentially always after medullary nailing. The entire medullary canal is involved, and will require debridement (nail removal and reaming).

- Type II osteomyelitis is superficial, may be present under a plate, but is rarely, if ever, seen with fracture-site infection.

- Type III osteomyelitis (localized full-thickness cortical involvement), will require debridement of all necrotic bone. During debridement, the full extent of the necrotic area becomes evident. This may weaken the bone, or produce significant dead space. Soft-tissue coverage may be inadequate and require reconstruction. Fracture healing may be a problem that requires identification and treatment.

- Type IV osteomyelitis diffusely involves the entire circumference of at least a segment of the bone. Usually the entire bone segment must be removed to eliminate necrotic tissue and persistent bacteria.

Host resistance to infection – Introduction

Patients vary in their ability to resist infection. In some cases, a patient’s response to infection is so impaired that all efforts at treatment fail. To understand the problem of posttraumatic infection, it is important to assess each patient’s immunocompetence.

Local factors are limited to the site of infection and include focal arterial insuffiency, venous stasis, previous radiation therapy, etc.

Systemic factors that impair host resistance include tobacco smoking, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic steroid use, HIV/Aids, etc.

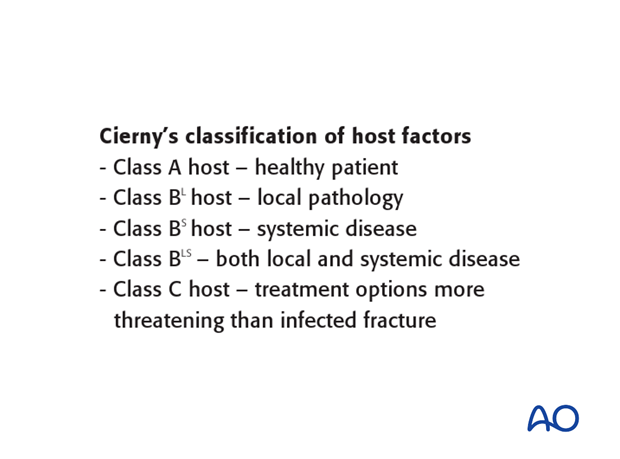

Cierny’s classification of host resistance to infection

Cierny has provided a classification scheme for host resistance in addition to that presented above for anatomical classification. Both local and systemic factors are involved. Cierny’s classification simplistically identifies the uncompromised patient as Class A. If significant compromise is identified, the patient is class B, either based on local factors (B L), systemic factors (B S), or both (B L,S).

Class C patients are either so compromised that the risks of treatment outweigh the benefits, or the symptoms of their infection are sufficiently limited that surgical treatment is not indicated.

Class A host

A class A host is a healthy patient. Their infection was not the result of impaired systemic host resistance. It must be remembered that a very severe injury can result in a focal defect of host resistance, because of locally impaired vascularity and tissue damage. An otherwise healthy patient with this degree of persisting local damage actually belongs in class B (B L).

Class A hosts are usually able to tolerate any appropriate surgical procedure. Tissue response to infection is strong, soft-tissue viability is excellent, and healthy tissue is available for transfer, if needed. With or without long-term antibiotics, the host is able to recover from a completely resected infection.

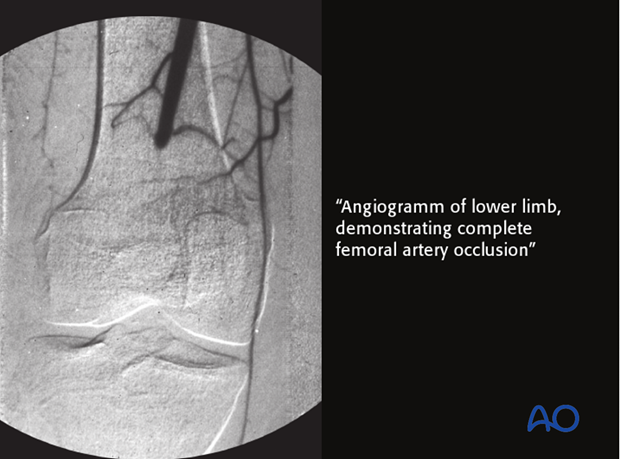

Class B L host – local disease

A class B L host has locally compromised soft tissue, or bone. The patient’s injury, or previous surgery, or both, may compromise tissue healing. For example, the patient may have had radiation, or previous injury to this region. Other potential local impairments are vascular disease or lymphedema, which impair wound healing and response to infection.

This particular patient’s localized ischemia may be correctable with arterial reconstruction, with improvement of his host resistance classification.

B S host – systemic disease

Many systemic diseases can affect a host, reducing ability to fight infection. Extremes of age, malnutrition and obesity are three very common causes of systemic host problems. Smoking, alcohol, steroids, etc. also compromise host resistance. Systemic diseases such as diabetes, renal or liver failure impair tissue response to infection.

With such patients, every effort must be made to identify and treat the systemic problems, but it is not always possible to restore normal host resistance. In practice, when dealing with an active infection, it is appropriate to begin treatment involving drainage, debridement and appropriate antibiotics, with minimally invasive fracture stabilization (external fixation). Preferably, impaired host resistance can be improved before definitive surgical reconstruction. If this is not possible, treatment failure, and/or amputation become likely.

Class C host – poor surgical candidate

Class C patients are either so compromised that the risks of treatment outweigh the benefits, or the symptoms of their infection are sufficiently limited that surgical treatment is not indicated.

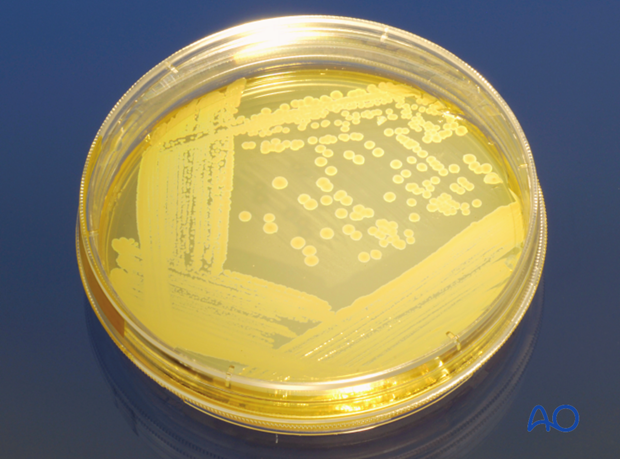

Bacteriology

Bacteriology of fracture wound infection

- One, or more, bacterial species may be present

- Source: patient’s skin, scene of injury, hospital contamination

- If signs of infection, get multiple surgical (deep wound) specimens for culture and sensitivity

Click here to read more about bacteriology.

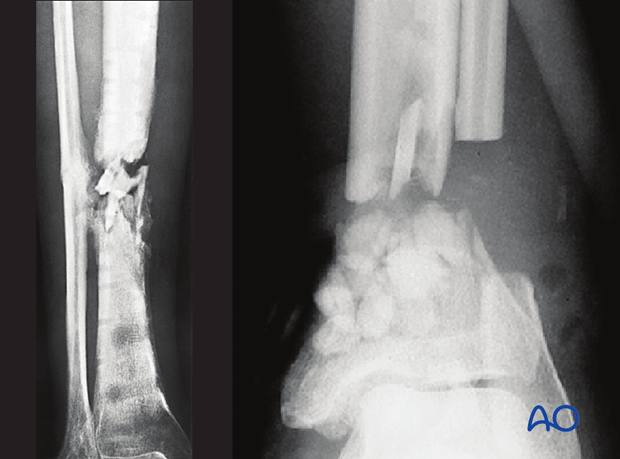

Fracture union and fixation devices

Fracture infections are influenced by factors involving the fracture and its prior treatment. Infections interfere with fracture healing. Infections are harder to eradicate from nonunited fractures. Treatment plans must address a nonunion, if it exists, with decision about bone resection, stabilization, bone grafting, etc.

Fracture fixation devices impair host resistance. If they provide absolute stability, this benefit may overcome their detrimental effects. Thus, in carefully selected cases (low-virulent organisms and healthy tissues), internal fixation may be retained, if stability is adequate.

If there is instability, or the infection fails to resolve promptly, plates, or intramedullary nails should be removed, and replaced with external fixation.