ORIF - Lag screw fixation

1. Introduction

Coracoid fractures are typically associated with more complex fractures of the scapula, and/or clavicle, and may also involve the suspensory ligament complex.

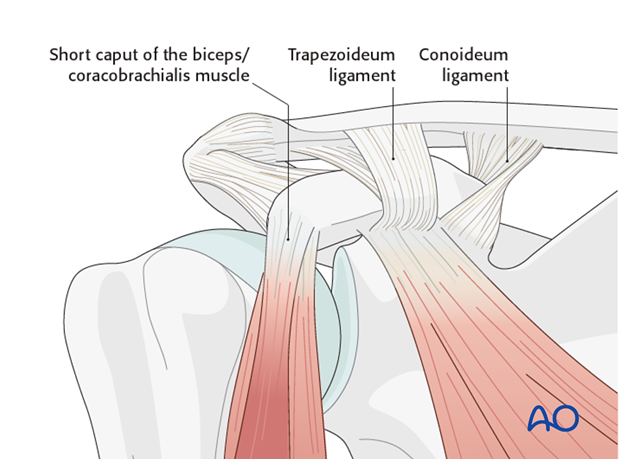

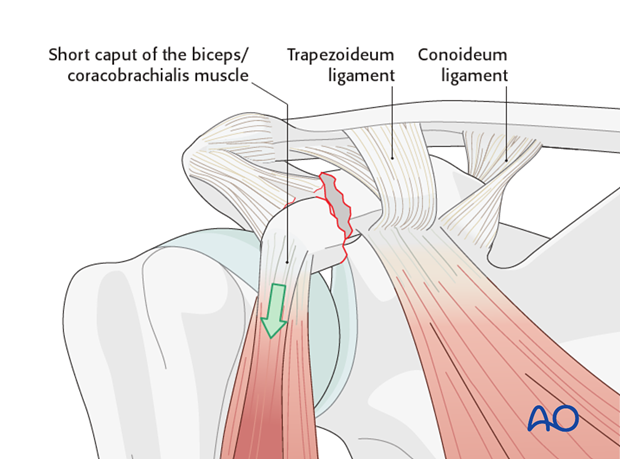

Coracoid base fractures should be differentiated from tip fractures as the surgeon needs to establish the exact location of the fracture line in relation to the coracoclavicular ligaments (coracoclavicular: trapezoideum, conoideum) and the inserted tendons (short caput of the biceps/coracobrachialis).

Any disrupted ligaments are treated as described in the section of LSSS.

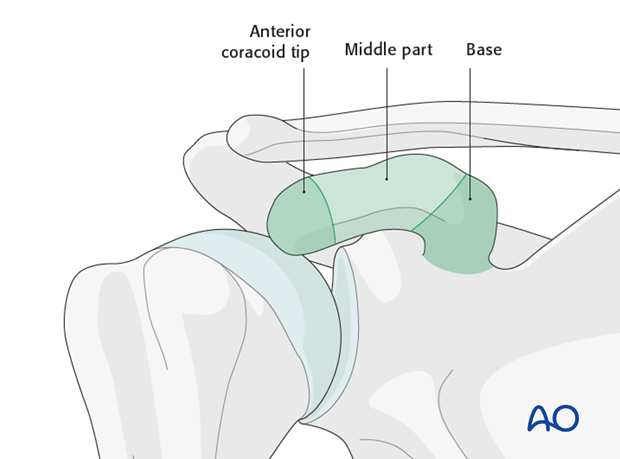

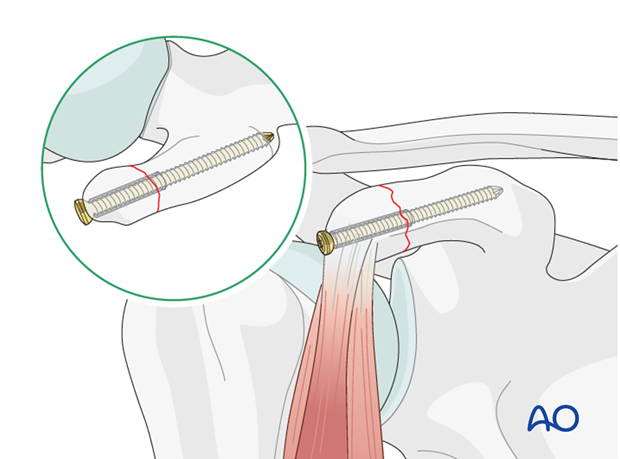

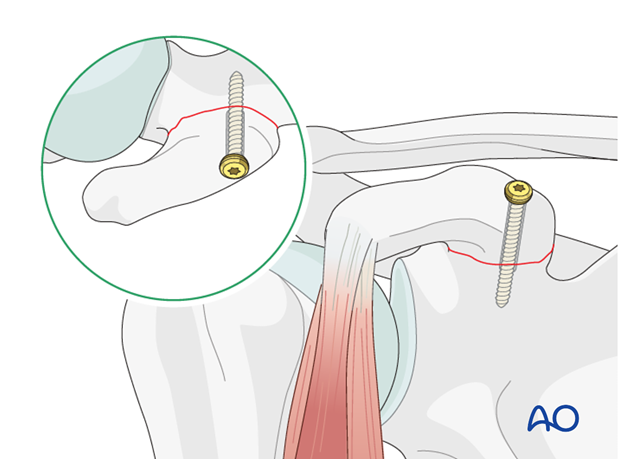

The coracoid projects anteriorly and inferiorly with a curved undersurface. The coracoid is divided into three parts, the middle part is flat, the anterior part bends forwards and downwards, and the posterior part runs to the base. This particular anatomical configuration must be kept in mind when screw fixation is used.

2. Patient preparation

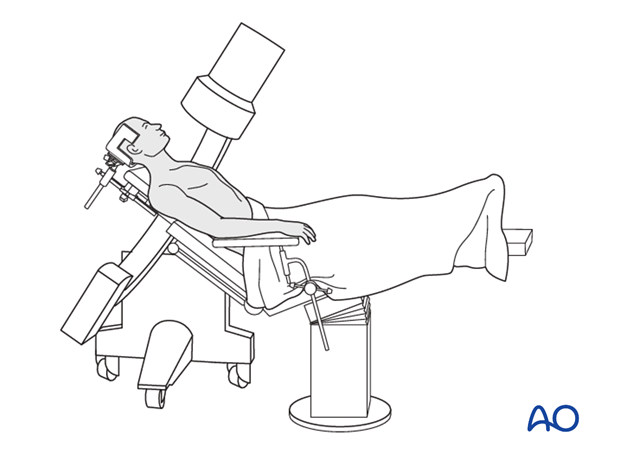

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a beach chair position.

3. Approach

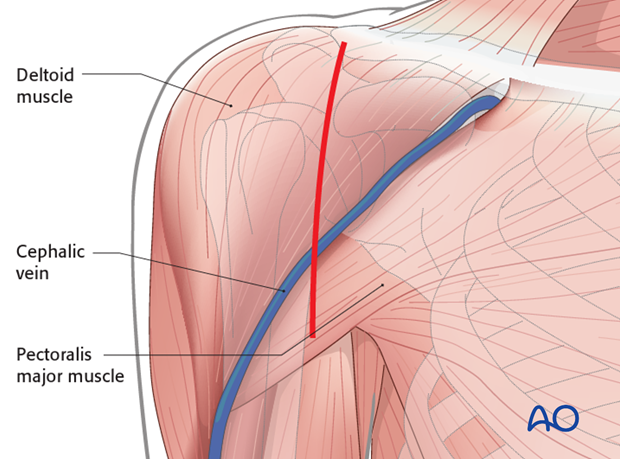

A superiorly extended deltopectoral approach may be used.

If the fracture line is lateral/distal to the coracoacromial ligaments, reduction may be made difficult by the pull of the short head of biceps tendon.

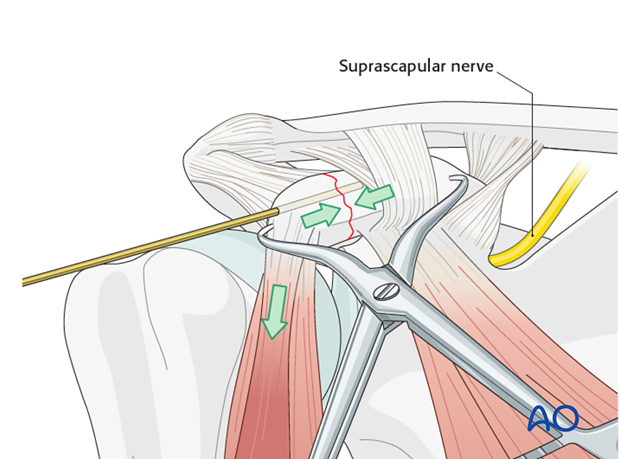

In this case the approach is extended superiorly to allow for the placement of a reduction clamp.

4. Reduction and fixation

Pearl: If the medial tip of the reduction clamp keeps slipping on the bone, drill a small 2.5 mm hole. This will give a grip for the medial tip of the reduction clamp

Once reduced a K-wire is inserted for temporary fixation.

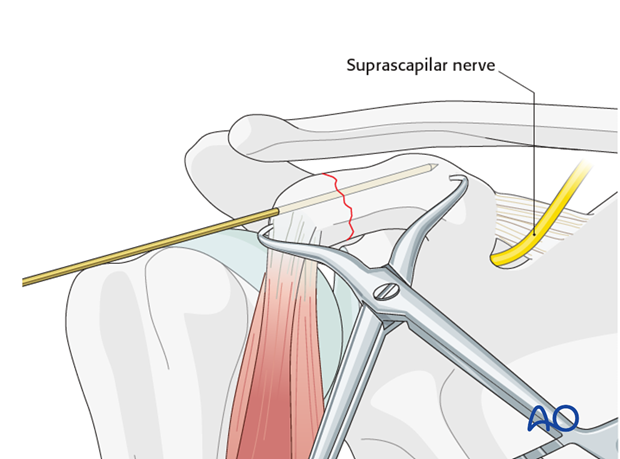

Care must be taken that the K-wire (and screw) do not enter the scapular notch as this may compromise the suprascapular nerve (controlling the supra- and infraspinatus muscle).

Check the reduction and temporary fixation with an image intensifier.

Insert your lag screw over the K-wire and then remove the K-wire and clamp.

Base fractures are fixed in a similar fashion as a tip fracture, however the screw is more posterior and almost vertical.

5. Aftercare

The aftercare can be divided into 4 phases:

- Inflammatory phase (week 1–3)

- Early repair phase (week 4–6)

- Late repair and early tissue remodeling phase (week 7–12)

- Remodeling and reintegration phase (week 13 onwards)

Full details on each phase can be found here.