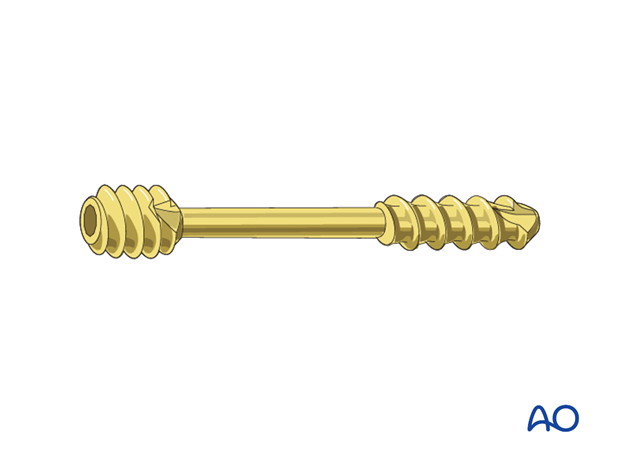

Lag screw

1. General considerations

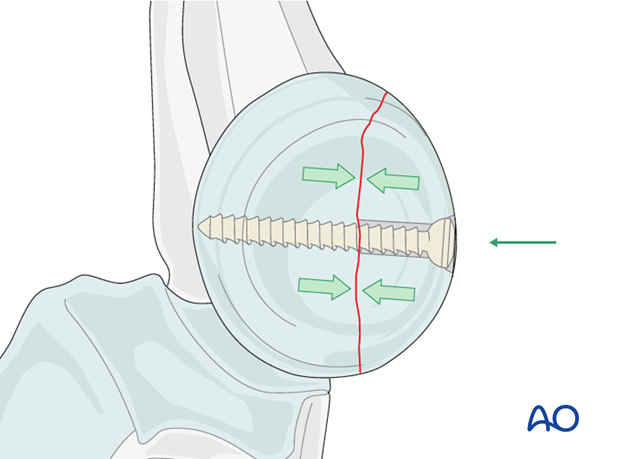

Lag screw principles for the radial head

In two-part partial articular fractures of the radial head, fixation can be achieved by lag screws.

The thread pulls the opposite bone fragment towards the head of the screw placing the fracture ends under compression. The portion of the thread in the gliding hole does not purchase in the surrounding bone.

Because the radial head is completely covered by articular cartilage the screw heads must be countersunk just below the level of the articular cartilage. The screw tip must not protrude medially, as it will contact the ulna and interfere with supination/pronation.

2. Screw positioning

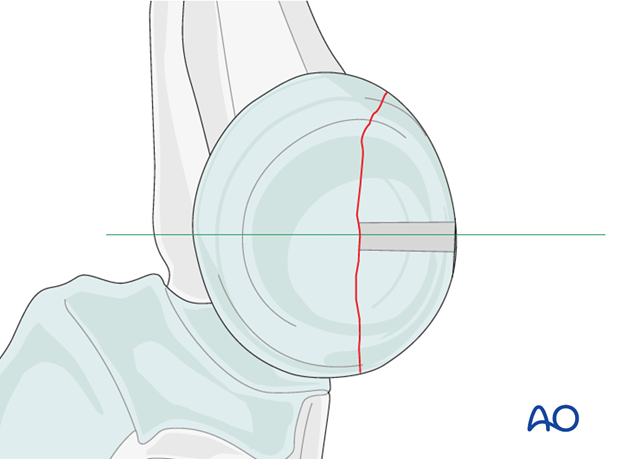

For the insertion of the screws, choose a location in the radial head that causes the least compromise of full pronation and supination. Insert the lag screw(s) as perpendicularly to the fracture plane as possible.

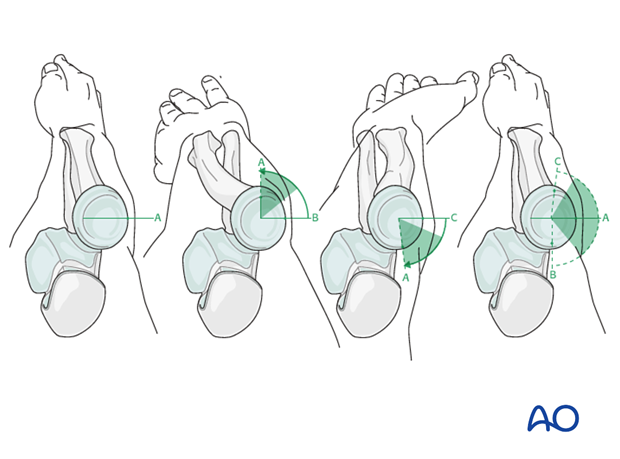

Safe zone for screw insertion

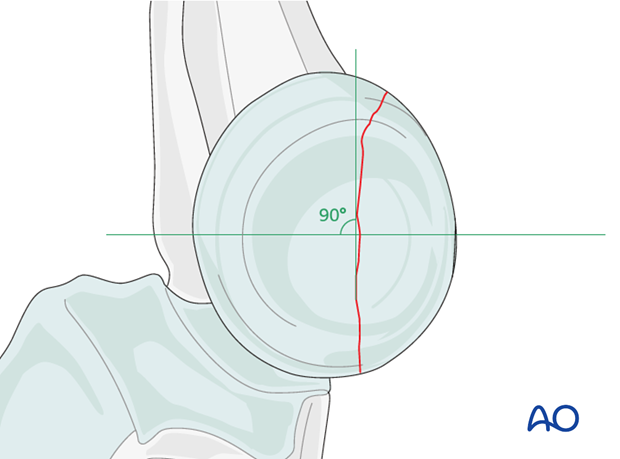

To determine the location of the “safe zone”, reference marks are made along the radial head and neck, to mark the midpoint of the visible bone surface. Three such marks are made with the forearm in neutral rotation, full pronation, and full supination as shown in the illustration. The posterior limit of the safe zone lies halfway between the reference marks made with the forearm in neutral rotation and full pronation. The anterior limit lays nearly two thirds of the distance between the neutral mark and the mark made in full supination.

Note: The nonarticulating portion of the safe zone for the application of implants to the radial head (or safe zone for prominent fixation) consistently encompasses a 90 degrees angle localized by palpation of the radial styloid and Lister’s tubercle.

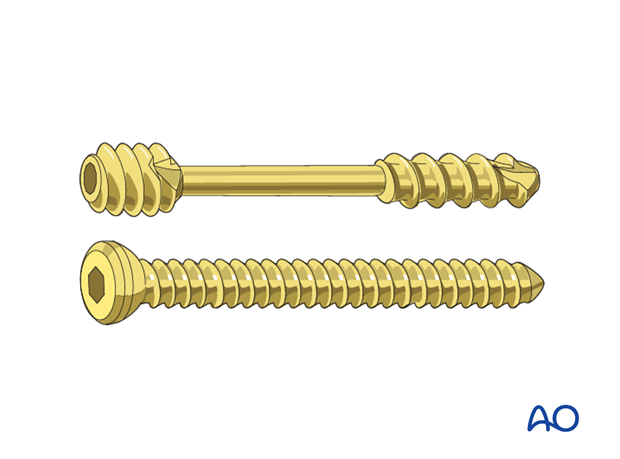

3. Choice of implant

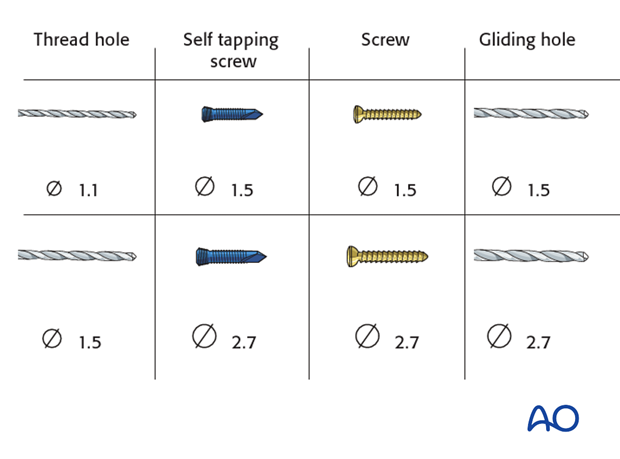

1.5 mm or 2.0 mm screws, or headless compression screws (Herbert or similar screws) are used.

4. Positioning and approach

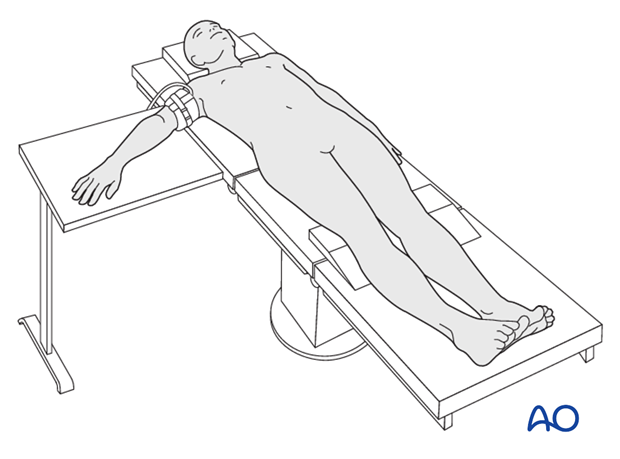

Positioning

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position for lateral access.

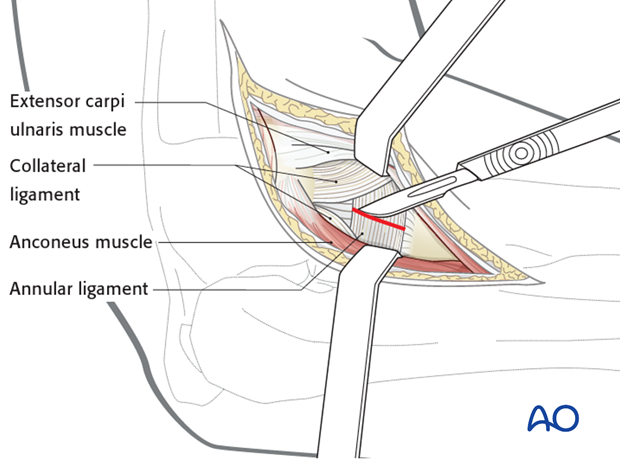

Approach

For this procedure a lateral approach is normally used.

5. Reduction and preliminary fixation

Reduction of stable fractures

In minimally displaced and stable fractures, there is no need to open the fracture site. The deformity can be corrected using a tamp.

Reduction of unstable fractures

In unstable fractures, the fracture can be opened to clear out soft tissue, hematoma and interposed fragments.

Expose the fracture ends with minimal soft tissue dissection.

If the radial head has been dislocated posteriorly, confirm that it is satisfactorily reduced to the capitellum.

Reduction is achieved directly.

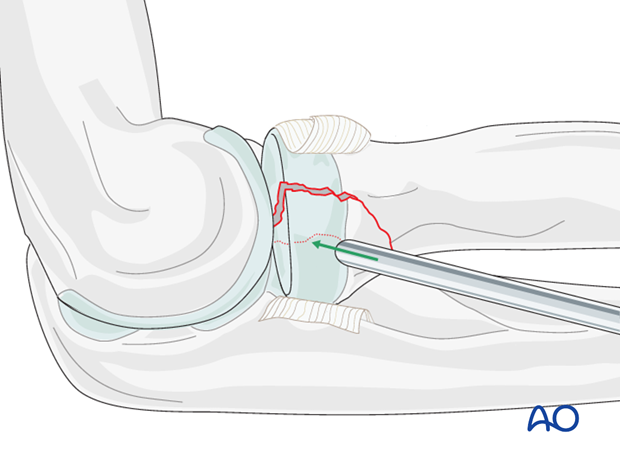

If the annular ligament is still intact, cut and retract it to achieve better access to the fracture site.

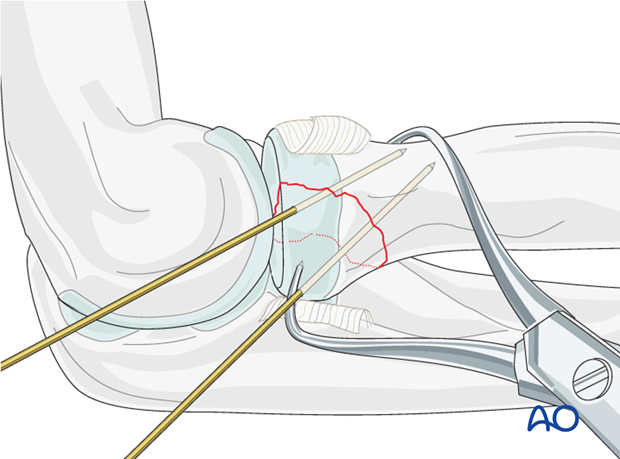

Reduce and provisionally fix the fracture with the help of small pointed reduction forceps and one or two K-wires.

Anticipate the final screw position prior to temporary K-wire placement.

6. Screw positioning

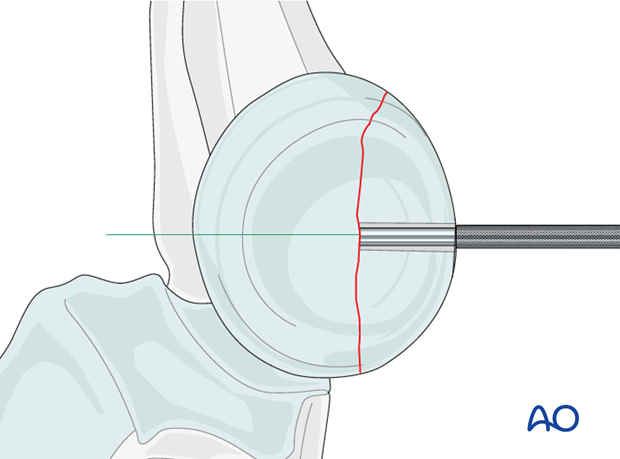

Drilling

Plan the number and location of screws.

The lag screw is ideally directed perpendicularly to the fracture plane.

Drill a gliding hole into the free fragment, sized according to screw size.

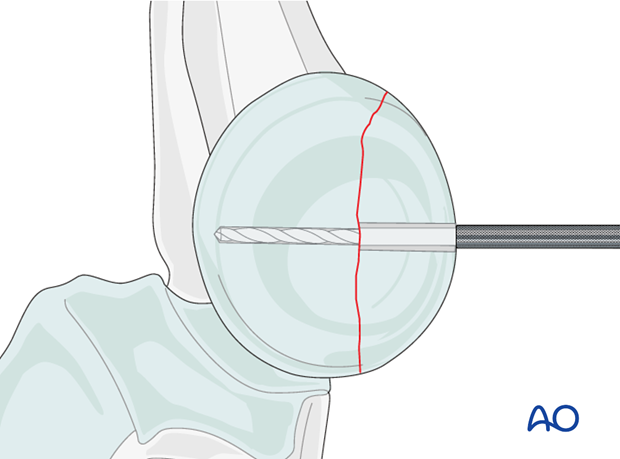

Insert the appropriate drill sleeve into the gliding hole until it reaches the fracture.

Now drill the epiphysis of the intact radial head with the appropriate drill bit.

Countersinking and measuring

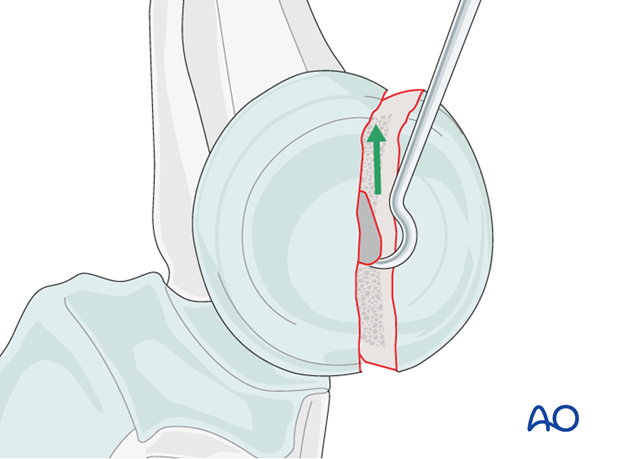

Countersink the cartilage covering the free fragment to prevent protrusion of the screw head.

Measure the depth of the hole and place the screw. If self-tapping screws are not available, tap the far epiphysis with the appropriate cortical tap and protection sleeve.

Note: Always measure after countersinking to prevent penetration of the screw tip into the joint.

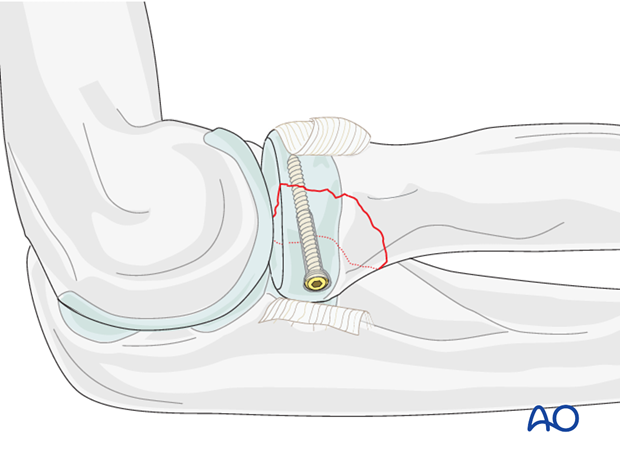

Lag screw insertion

Closely observe the compression effect on the fracture line while tightening the lag screw.

Any K-wire(s) should be removed just before the final tightening of the screw.

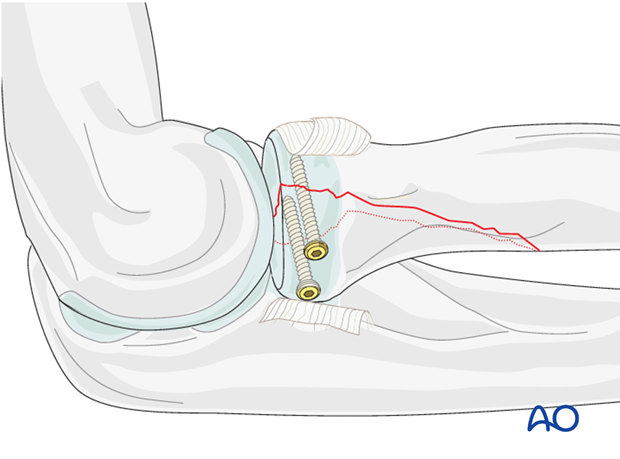

Second lag screw

If fragment size permits, a second lag screw will improve strength of fixation. It can be inserted now using the same technique as described above.

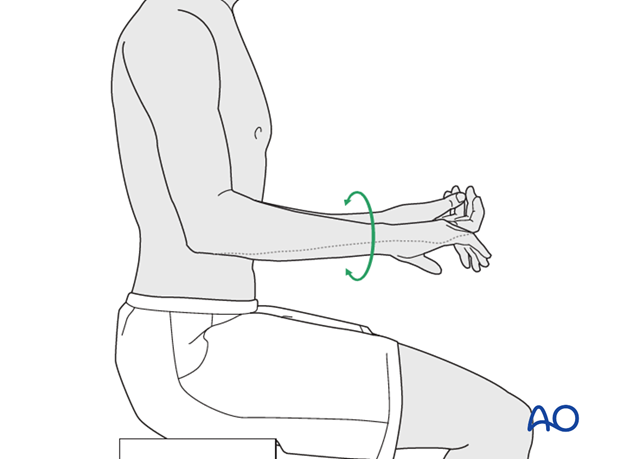

Note: Check reduction and screw length with supination/pronation exam. Screws should not obstruct rotation.

Alternative fixation - headless compression screws

When headless compression screws (eg, Herbert or HCS) are used, there is no need for countersinking as the screw head engages inside the bone.

After reduction, provisionally fix the fracture inserting one or two K-wires in the previously planned screw position. Over the K-wire, insert the cannulated screw.

Preparation for screw insertion should be performed according to the surgical technique of the specific screw.

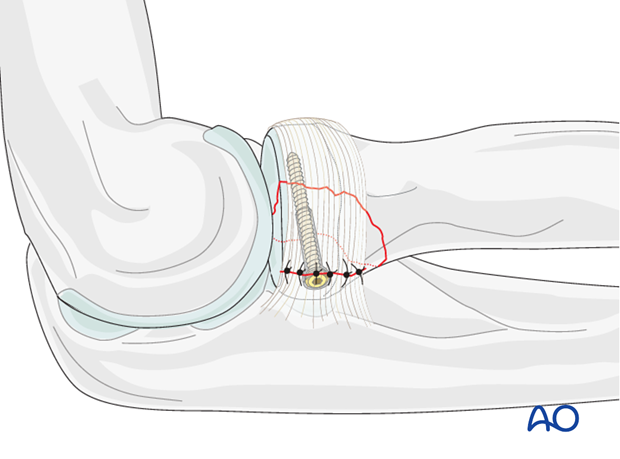

7. Ligament repair

Repair the annular ligament using non-absorbable sutures.

8. Final assessment

Also check supination and pronation. Fixation should be stable. Crepitus or restricted motion should be absent.

Check fractures and fixation with image intensifier or x-ray.

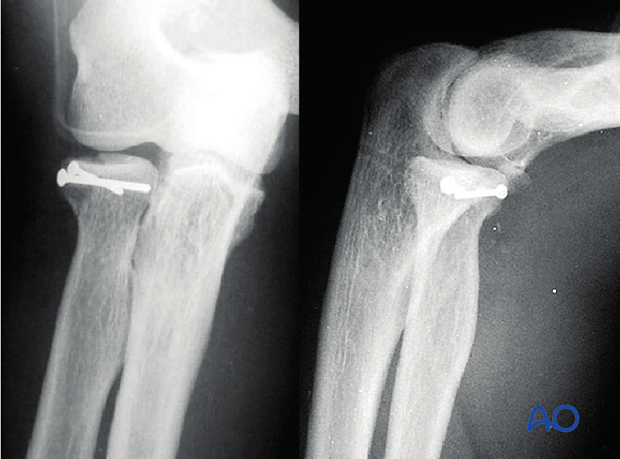

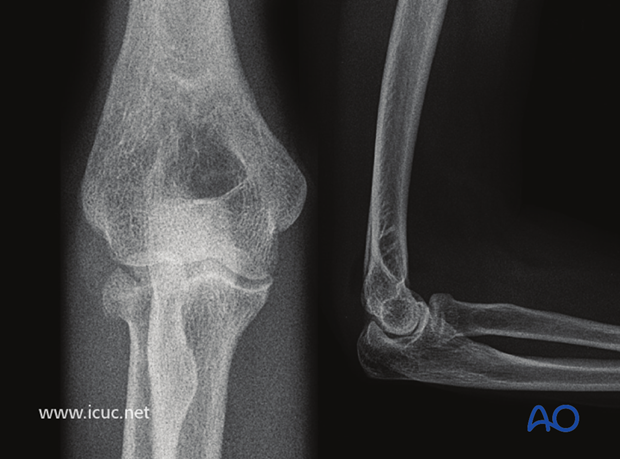

9. Case

AP and lateral images showing a partial articular radial head fracture with displacement.

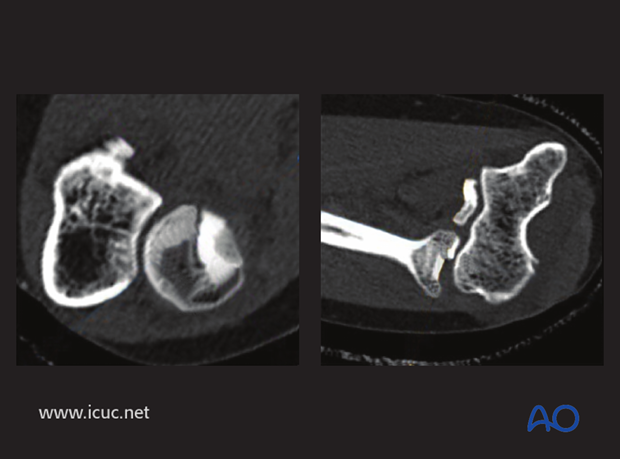

Two images with CT showing partial articular radial head fracture.

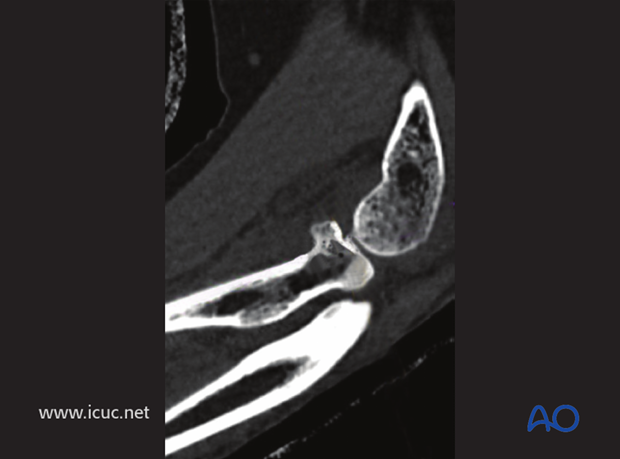

Sagittal cut with anterior radial head articular displacement

3D-CT image showing anterior radial head displacement.

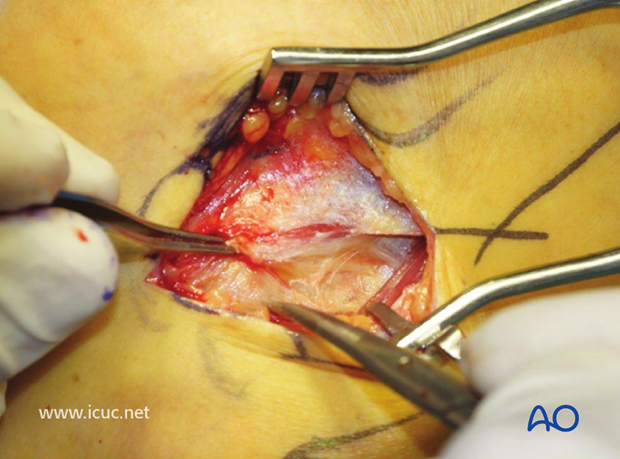

Anatomic landmarks for incision drawn on the patient's right elbow.

An incision is made in the fascia between the anconeus and extensor digitorum communis.

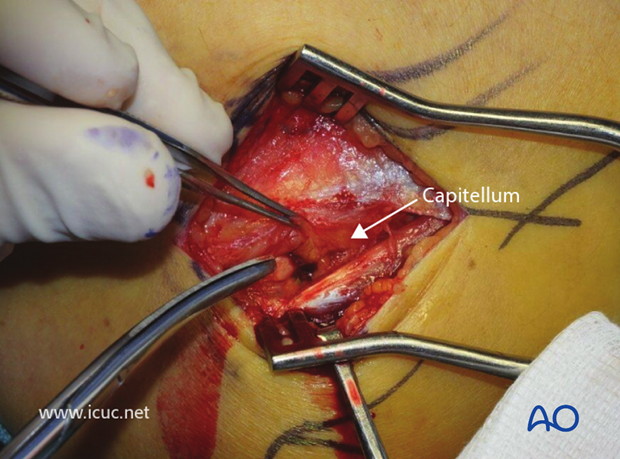

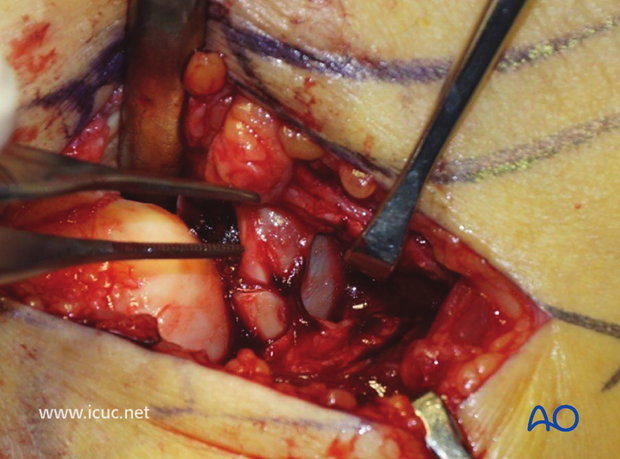

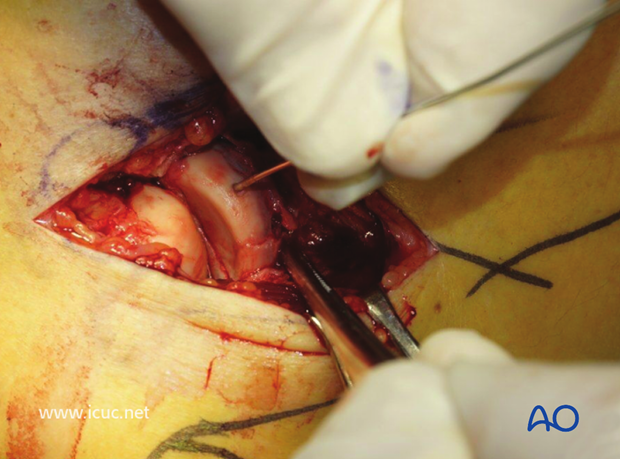

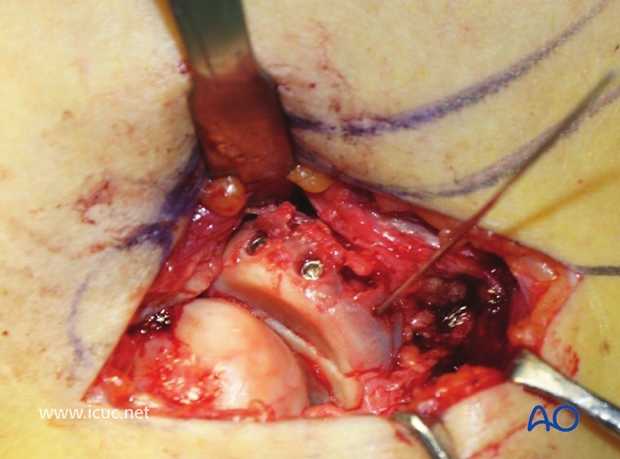

This image shows the joint capsule open and the arrow pointing at the capitellum.

By carefully dissecting distally, the radial head and its fracture can be seen. The dissection distally must not go beyond the radial neck for fear of injuring the posterior interosseous nerve.

The step in the joint can be seen and the articular injury assessed.

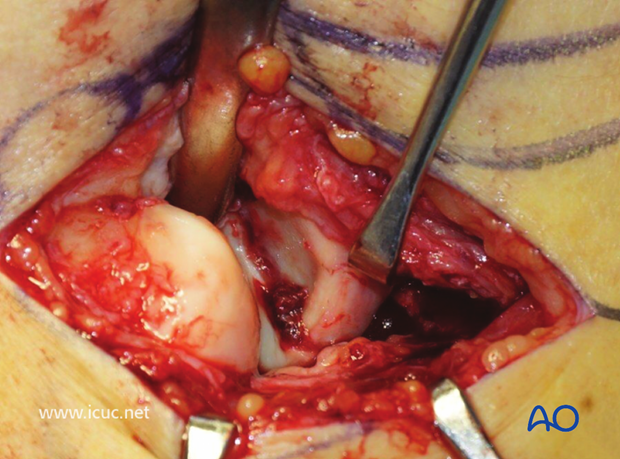

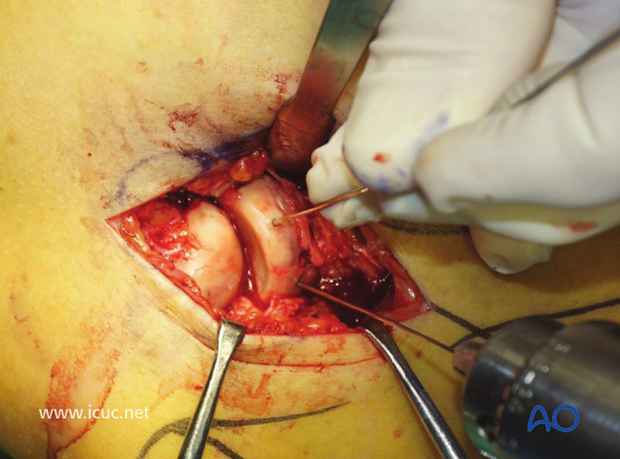

The fracture has been cleaned and is ready for reduction.

A joystick is placed in the anterior radial head. A chisel is used as a lever in the fracture site to gently reduce the displaced fracture.

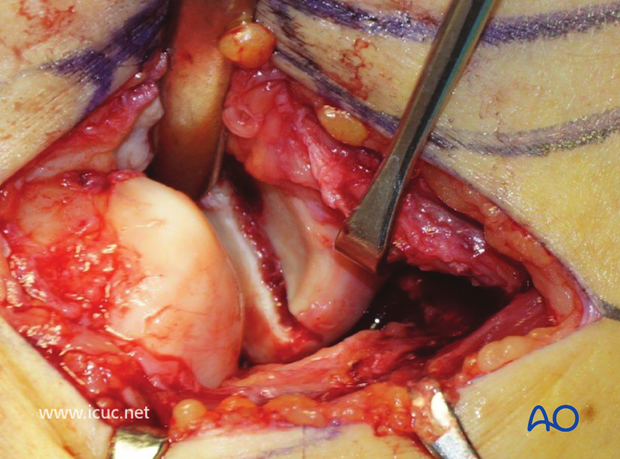

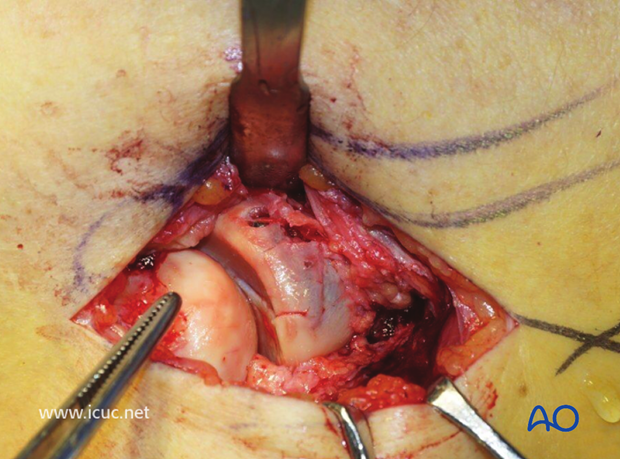

The fracture is near perfectly reduced in this image and the K-wire can be advanced.

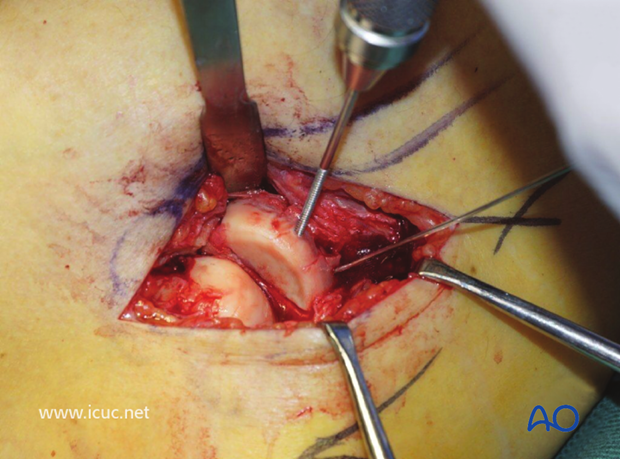

A second K-wire is used to secure the reduction in two planes.

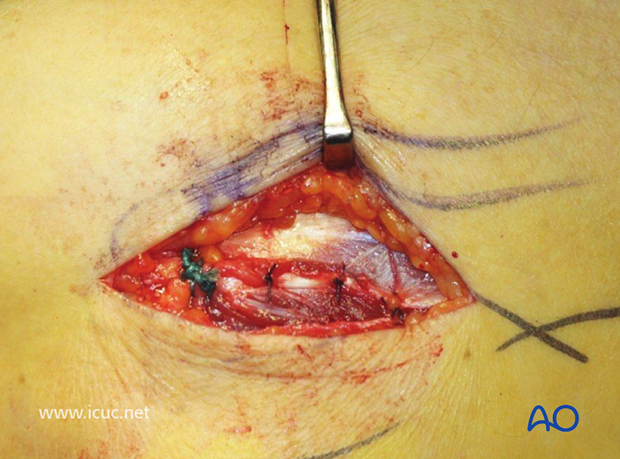

A small lag screw is applied. It must be long enough to ensure purchase in the intact part of the radial head, whilst remaining subchondral and not entering the joint.

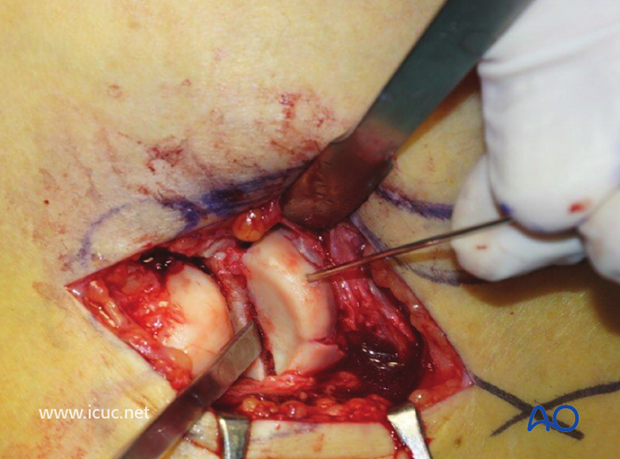

As this surface is articular, screw heads must not protrude, so the drill hole is countersunk. This image shows the first hole has been drilled and tapped and the tap left in place to help stabilize the fragment while the second hole was drilled, tapped, and countersunk.

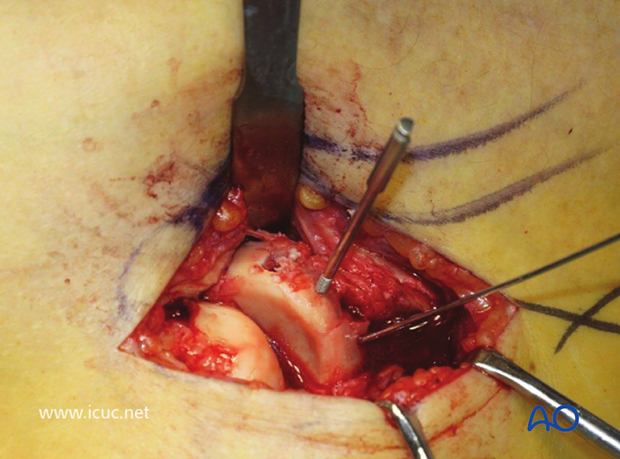

Both screws have been inserted.

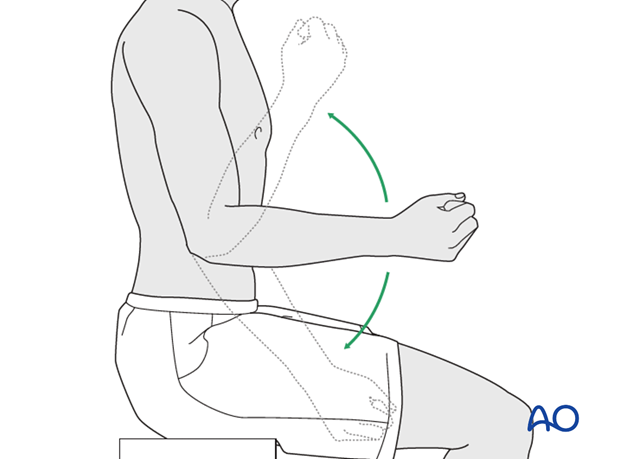

Once fixation is finalized, the forearm needs to be taken through a full range of pronation and supination to ensure that there is no block to rotation.

The interval has been closed with the deep fascia

Skin closure

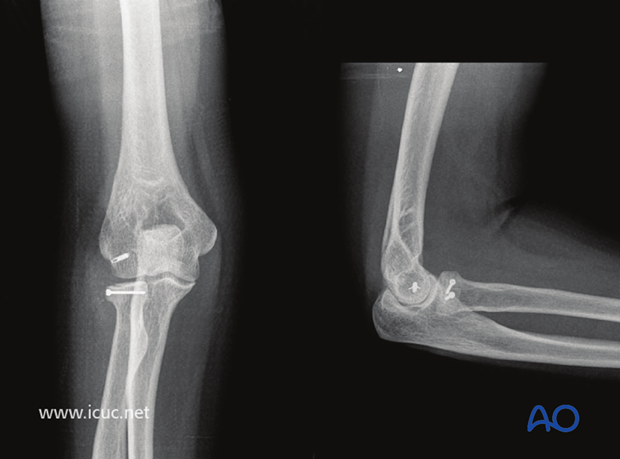

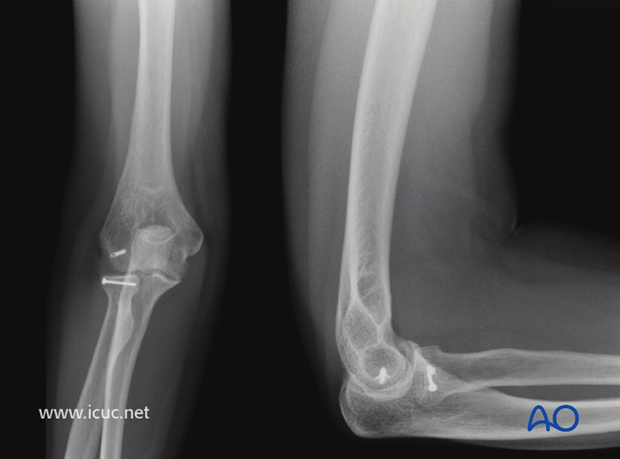

Four week X-ray images showing nice reduction and suture anchor left in the lateral epciondyle

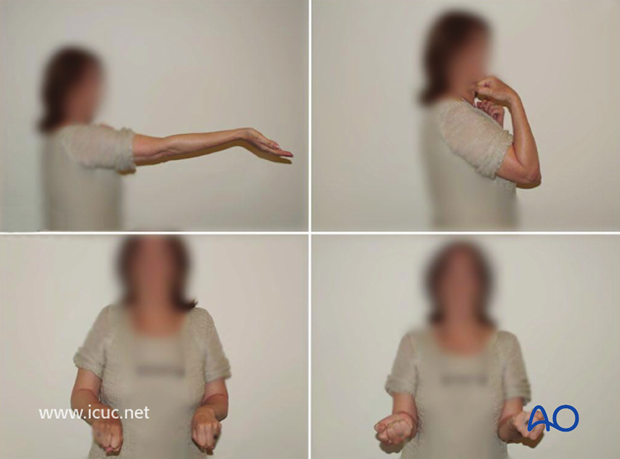

8 week clinical outcome.

4 year X-ray images.

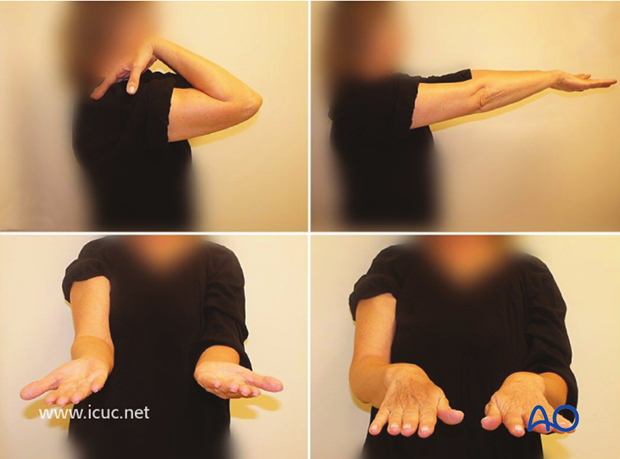

Four year final clinical images

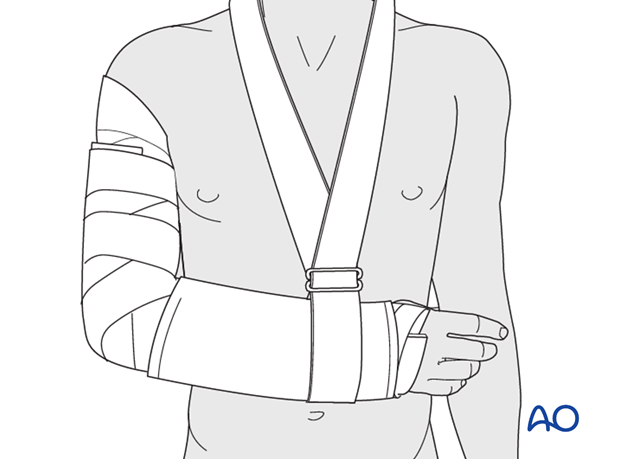

10. Postoperative treatment following ORIF

Postoperatively, the elbow may be placed for a few days in a posterior splint for pain relief and to allow early soft tissue healing, but this is not essential. To help avoid a flexion contracture, some surgeons prefer to splint the elbow in extension.

If drains are used, they are removed after 12–24 hours.

Mobilization

Active assisted motion is encouraged within the first few days including gravity-assisted elbow flexion and extension. Encourage the patient to move the elbow actively in flexion, extension, pronation and supination as soon as possible. Delay exercises against resistance until healing is secure.

Use of the elbow for low intensity activities is encouraged, but should not be painful.

Range of motion must be monitored to prevent soft tissue contracture.

Prevent loading of the elbow for 6–8 weeks.

Monitor the patient to assess and encourage range of motion, and return of strength, endurance, and function, once healing is secure.

Follow up

The patient is seen at regular intervals (every 10–20 days at first) until the fracture has healed and rehabilitation is complete.

Implant removal

As the proximal ulna is subcutaneous, bulky plates and other hardware may cause discomfort and irritation. If so, they may be removed once the bone is well healed, 12–18 months after surgery, but this is not essential.