Open reduction - Screw fixation

1. General considerations

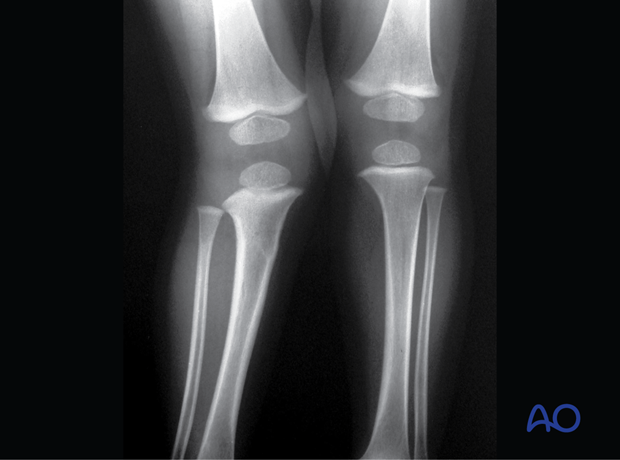

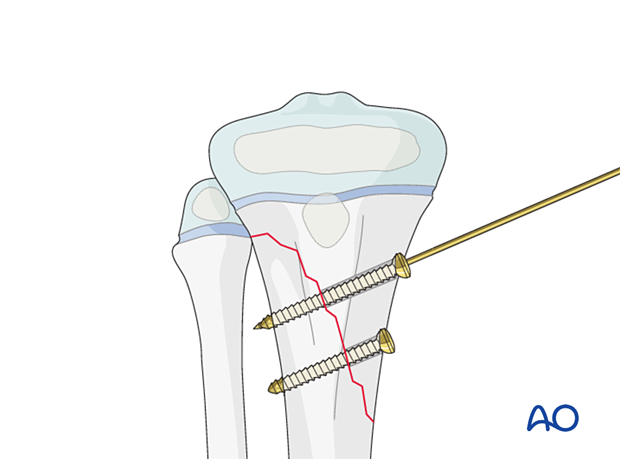

Screw fixation of oblique metaphyseal fractures is indicated in older children with unstable fractures, which cannot be sufficiently stabilized with a cast or K-wires.

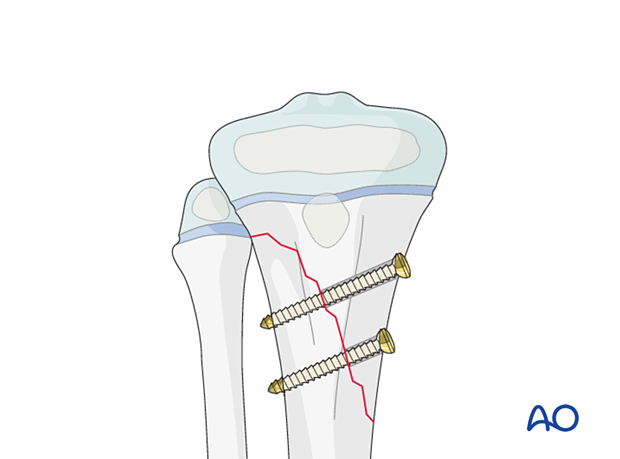

At least two screws should be used. They should be inserted perpendicular to the fracture plane.

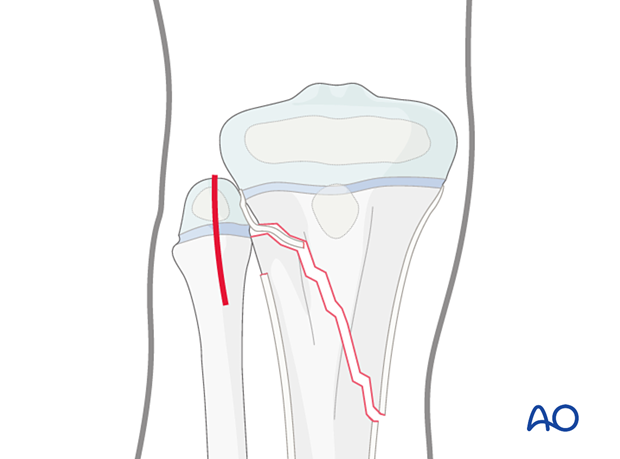

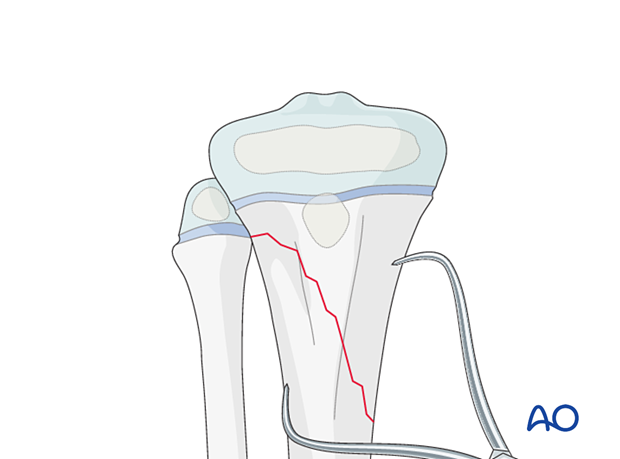

Closed vs open reduction

If initial closed reduction is unsuccessful, this is usually due to periosteum entrapped on the side that has failed in tension.

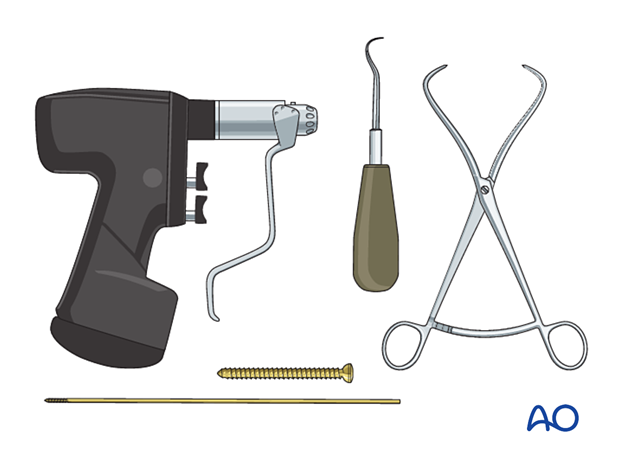

2. Instruments and implants

Appropriately sized cannulated or noncannulated lag screws (2.7, 3.5, or 4.0 mm) can be used.

The following equipment is used:

- Screw set or cannulated screw set

- Reduction forceps

- Dental pick

- Drill

- Image intensifier

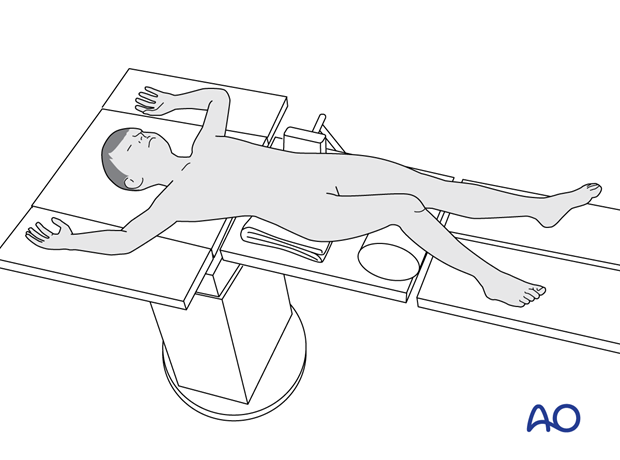

3. Patient preparation

Place the patient in a supine position on a radiolucent table, with a bolster under the ipsilateral flank.

Breaking the table to allow knee flexion may facilitate traction and reduction.

4. Approaches

The approach is dictated by the fracture pattern and location of the block to reduction (eg, periosteum). Screws may be inserted percutaneously.

5. Reduction

If acceptable closed reduction cannot be obtained, proceed to an open reduction.

Direct reduction should be possible after removal of entrapped soft tissue or bone fragments.

Correct rotation, angulation, and displacement.

The reduction may be performed and maintained with reduction forceps.

A temporary K-wire may be inserted.

In multifragmentary fractures, Small wedge fragments usually do not need reduction and fixation.

6. Fixation

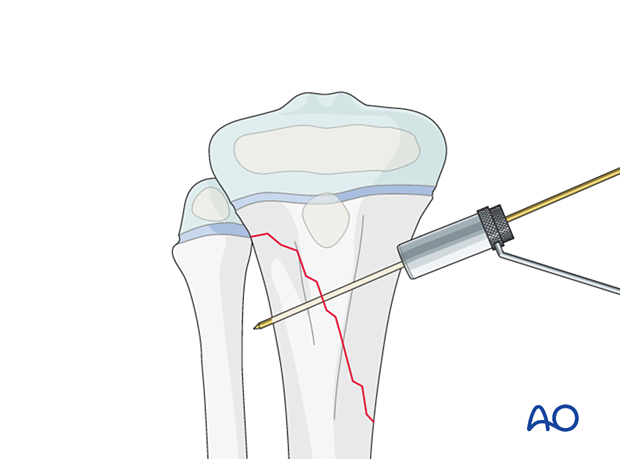

Incision

Perform a stab incision at the level of the planned screw insertion.

Spread the underlying soft tissues with blunt dissection and place a tissue protector down to the bone.

Insert the guide wire.

Screw insertion

Insert at least two lag screws in a standard manner.

Make sure the physis and perichondral ring are not compromised.

Confirm reduction, fracture stability, and screw placement with an image intensifier prior to removal of the guide wire.

7. Final assessment

Confirm fracture reduction and implant position with an image intensifier.

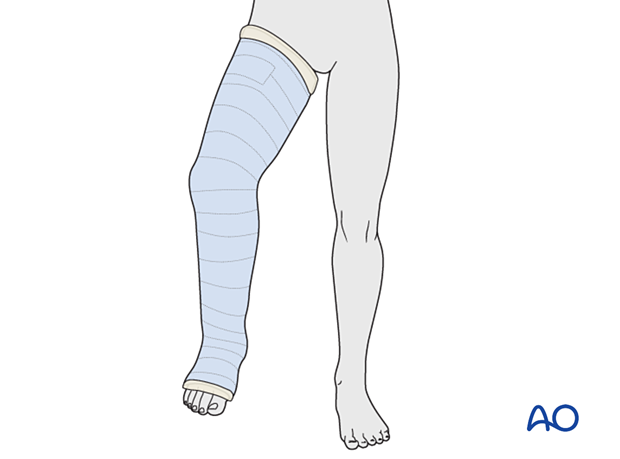

8. Application of a cast

The fixation should be protected with a long leg cast with the knee flexed 30°–45° for 3 weeks.

Alternatively, a knee orthosis may be used.

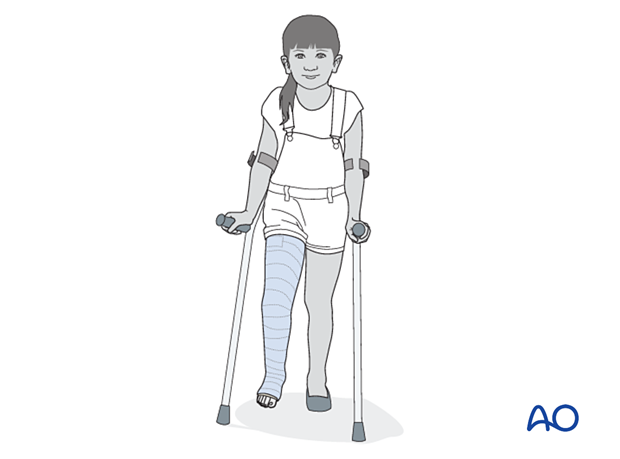

9. Aftercare

Immediate postoperative care

The patient is kept touch-weight bearing.

Older children may be able to use crutches or a walker.

Younger children may require a period of mobilization in a wheelchair.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently in the initial period following the injury, to exclude neurovascular compromise or evolving compartment syndrome.

High-energy fractures are associated with vascular injuries and require careful clinical assessment.

Follow-up

The first clinical and radiological follow-up is usually undertaken at 4–6 weeks.

Mobilization

Weight bearing can be started when clinical and radiological signs suggest a stable fracture, typically 3–4 weeks after injury.

Implant removal

Screw removal is optional and can be performed at least 3–4 months after injury.

Follow-up for growth disturbance and deformity

All patients with fractures of the proximal tibia should have clinical and radiological examination 8–12 weeks postoperatively to confirm healing and alignment.

Clinical examination should be repeated at intervals for at least one year to detect early signs of growth disturbance.

If there is a clinically relevant leg length discrepancy or malalignment, radiological assessment is required.

Check for valgus deformity which may develop over several months with greenstick fractures (Cozenʼs phenomenon). This occurs in younger patients and usually improves within 2 years of injury.