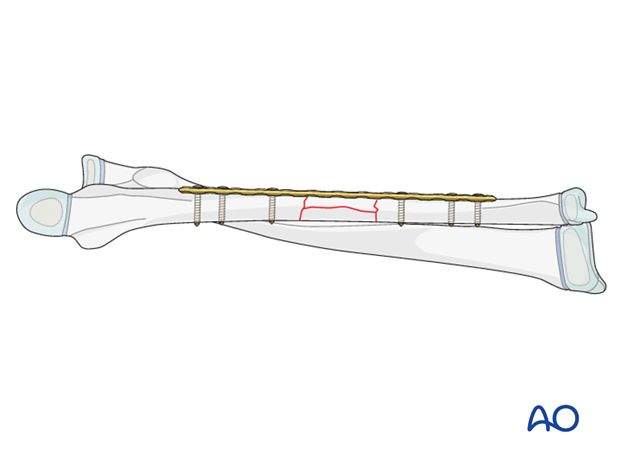

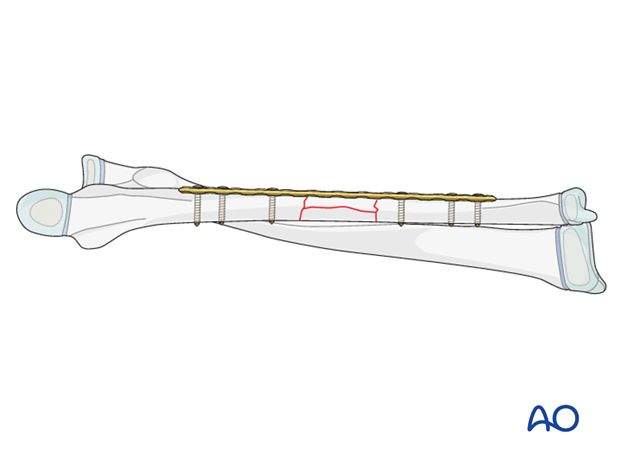

Monteggia lesion, multifragmentary fracture of ulna: open reduction, bridge plating

1. Introduction

General considerations

Plating is the standard technique for treating forearm fractures in adults and is therefore best considered for skeletally mature or nearly mature children.

Children with open physes have thick active periosteum favoring stability and rapid healing with the ESIN method. Where such techniques are unavailable plating may be used in younger children.

If technically possible, ESIN is biologically favored. If plating is used, soft-tissue and periosteal stripping of the bone should be minimized.

Plating of multifragmentary forearm shaft fractures

Plating of pediatric forearm shaft fractures follows the technique for plate fixation in adults.

For multifragmentary forearm shaft fractures, bridge plating may be applied. This results in relative fracture stability.

2. Principles

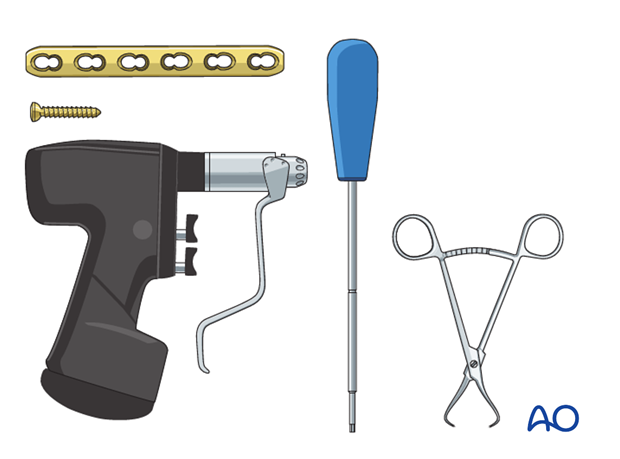

Instruments and implants

A small fragment set consists of:

- 2.7 or 3.5 mm plates and screws

- Power driver

- 2.7 or 3.5 mm insertion set

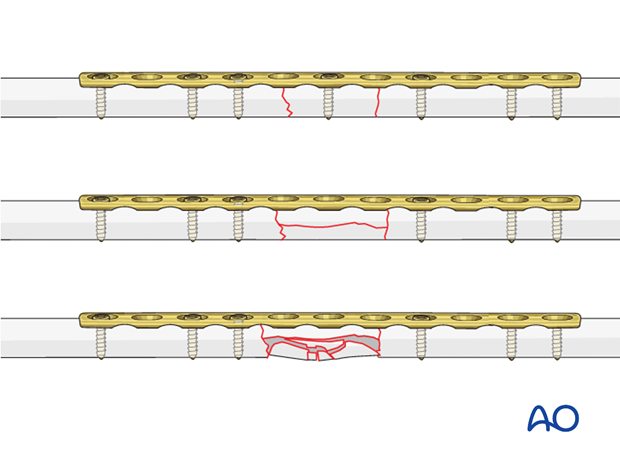

Choice of implant

The requirements for internal fixation of complex multifragmentary forearm fractures include:

- The plate should span any comminuted zone and provide at least a three-hole segment over each main fragment, with at least two bicortical screws in each main fragment.

- Well-spaced screws to distribute the stresses on the bone-implant composite for each main fragment

Plate position

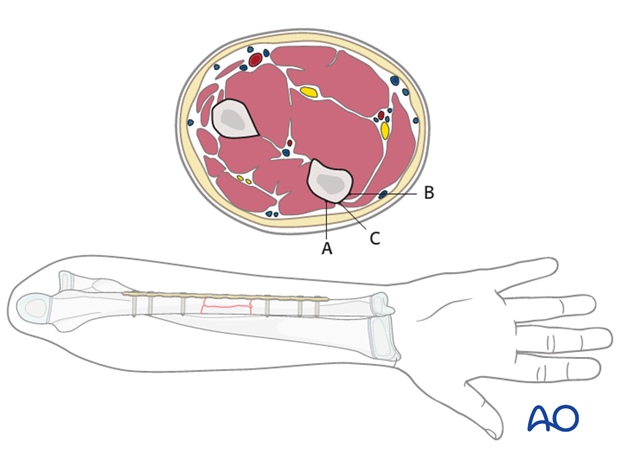

The ulnar plate can be positioned under the extensor carpi ulnaris (A), under the flexor carpi ulnaris (B), or in the interval between extensor and flexor carpi ulnaris (C).

With a more proximal fracture it can be more difficult to place the plate underneath the extensor muscle.

With more distal fractures, plates should be placed in the interval between the extensor and flexor carpi ulnaris (C).

Plating the tensile (subcutaneous) aspect of the ulna (C) is biomechanically preferable, but plate prominence can be a cause irritation.

Plates in positions A or B are covered by the muscle compartment and avoids this complication.

In the following procedure, the plate positioned on the subcutaneous border of the ulna (C) is illustrated.

Approach

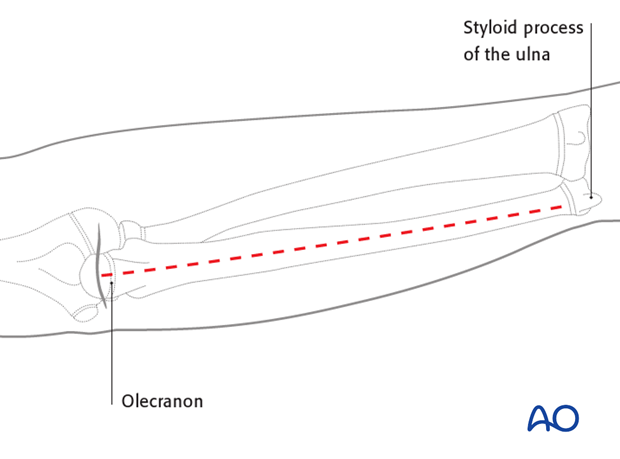

The ulna is exposed by the direct approach between the flexor and extensor muscle compartments.

3. Reduction

Reduction and fracture stability in children

Children’s periosteum is thick, tough tissue and is often intact on the concave (compression) side of a fracture.

Reduction maneuvers should be gentle to take advantage of stability of an intact periosteum.

Exaggeration of the fracture deformity may be required to loosen the periosteum and allow for gentle reduction.

In pediatric fractures there is often a combination of patterns of bone failure. Residual plastic deformity may prevent anatomical reduction of some of the fracture edges. Provided the alignment of the bone is anatomical and overall reduction is stable it is not necessary to perfectly reduce the entire fracture.

Open reduction

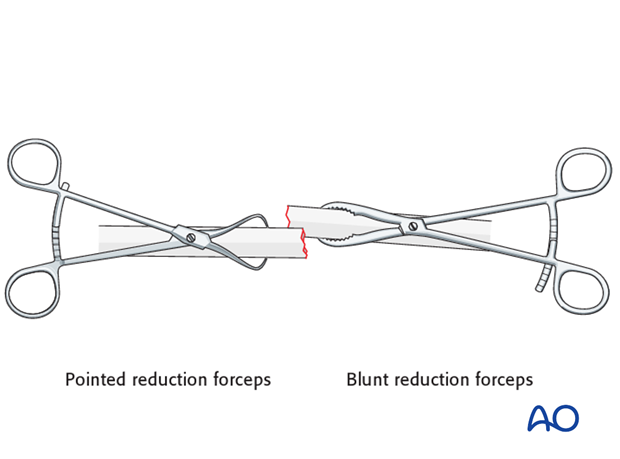

Reduce the fracture without extensive dissection of the fracture zone, using a reduction forceps on each main fragment.

The use of blunt, as opposed to pointed, reduction forceps can be helpful, particularly if greater forces are required.

Fix the plate to one fragment and then reduce the other main fragment onto the plate maintaining length, alignment and rotation.

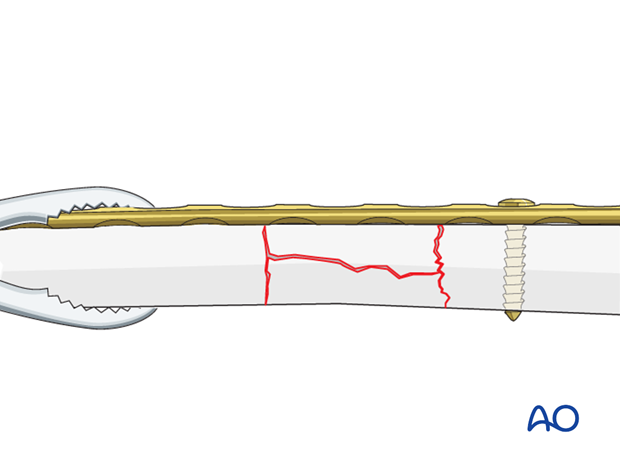

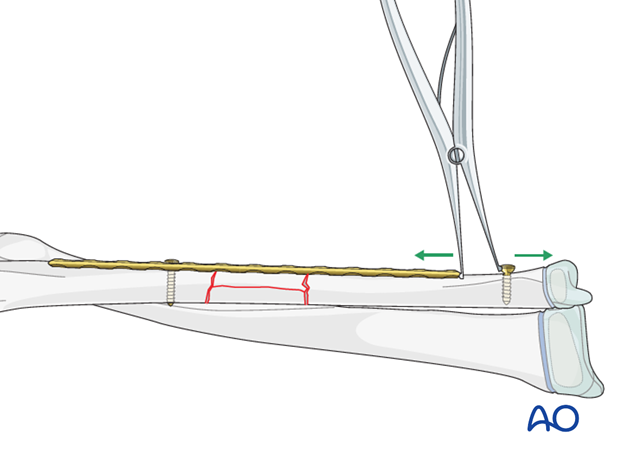

Plate assisted reduction and distraction using a laminar spreader and a screw (push-pull technique)

The plate is fixed to the proximal main fragment using a standard screw though the end hole.

Check that the rotational alignment is correct.

An independent screw is inserted into the distal main fragment a short distance (1-1.5 cm) beyond the distal end of the plate.

Use a laminar spreader between the independent screw and the end of the plate to distract the fracture, restoring length and axial alignment.

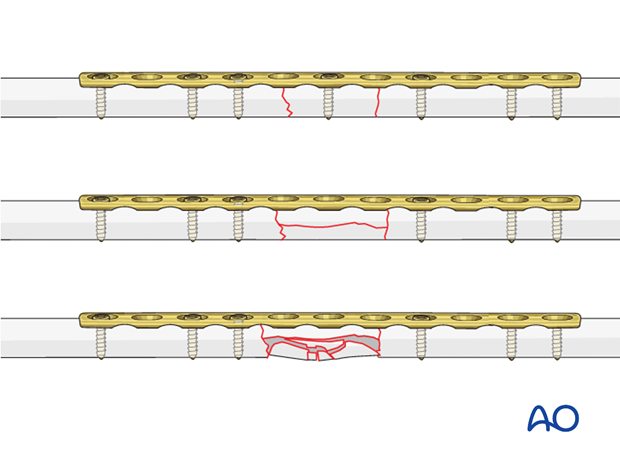

4. Plate length and number of screws

Three bicortical screws are suggested in each main fracture fragment due to the high torsional stresses.

Depending on its size, the intermediate fragment(s) may be fixed with bicortical screws or spanned by the plate, remembering that bridge plating is to achieve relative stability.

5. Fixation

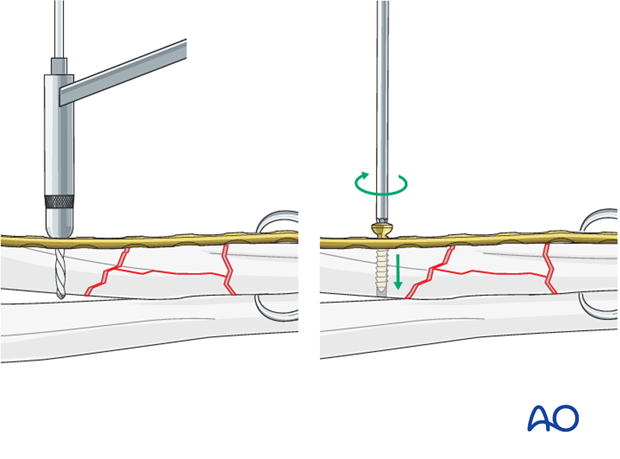

Insertion of 1st screw

Align a suitable plate to the bone, keeping in mind the shape of the yet unreduced fracture fragment.

Insert a neutral screw through the plate into one of the main fragments near the fracture line.

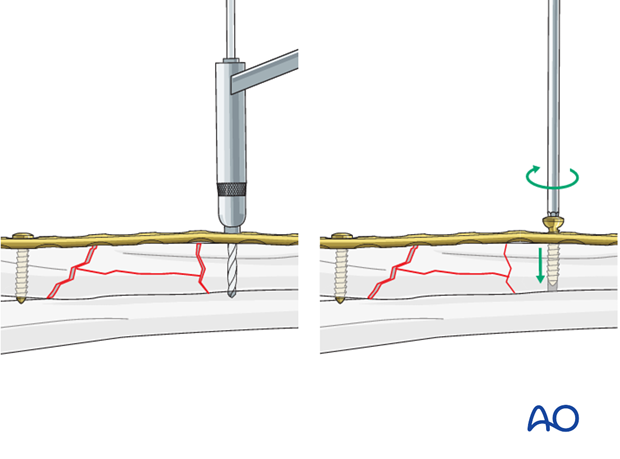

Insertion of 2nd screw

Insert a screw through the plate onto the other main fragment.

Optional: Fixation of intermediate fragment(s)

Secure the intermediate fragment(s) to the plate with a screw(s) if appropriate.

Completed osteosynthesis

Before inserting additional screws check reduction of the fracture and rotation of the forearm.

Insert the remaining screws.