Open reduction; plate fixation

1. General considerations

Introduction

Open plating is less biologically favorable because soft-tissue and especially periosteal stripping will slow fracture healing. In addition, muscle dissection can contribute to discomfort and joint stiffness.

Soft-tissue dissection should be minimized during open plating.

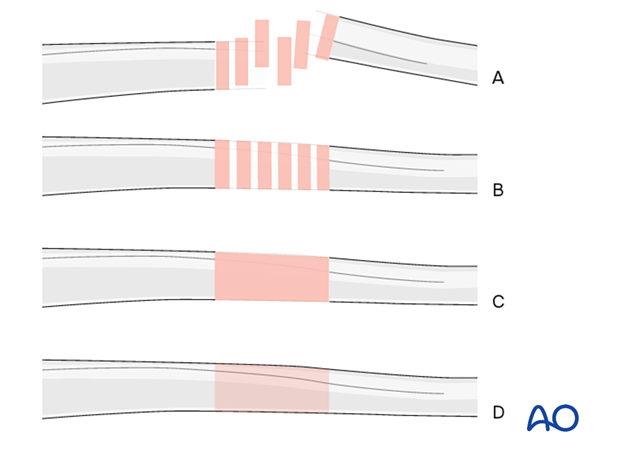

Throughout this section generic fracture patterns are illustrated as:

- Unreduced

- Reduced

- Reduced and provisionally stabilized

- Definitively stabilized

Compression vs bridge plating

Transverse and short oblique fractures can be made more stable by compressing using gliding holes in the plate.

Bridge plating relies on indirect fracture reduction.

Most children’s fractures heal readily and compression is not mandatory.

The approach that involves the least dissection of the fracture site to obtain stable fixation is preferred.

2. Selection of implants

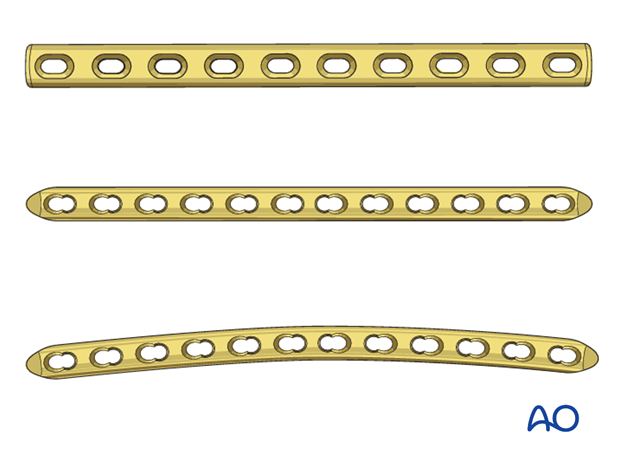

Plate size

For younger children a small fragment set can be used (3.5 mm). For older children and adolescents, a large fragment plate, typically a narrow 4.5 mm plate, can be used.

Plate length

Select a plate long enough to allow three bicortical screws in each main fragment.

If longer plates are used, a curved plate may provide a better fit and accommodate the sagittal anatomy of the femur.

An x-ray of the contralateral side is useful for templating.

3. Patient preparation and approach

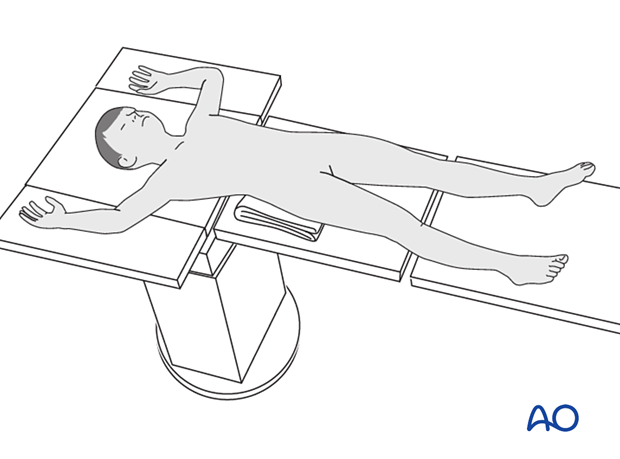

Patient positioning

Place the patient in a supine position on a traction table or a translucent table with a bump under the ipsilateral flank.

Approach

For this procedure a lateral approach is used.

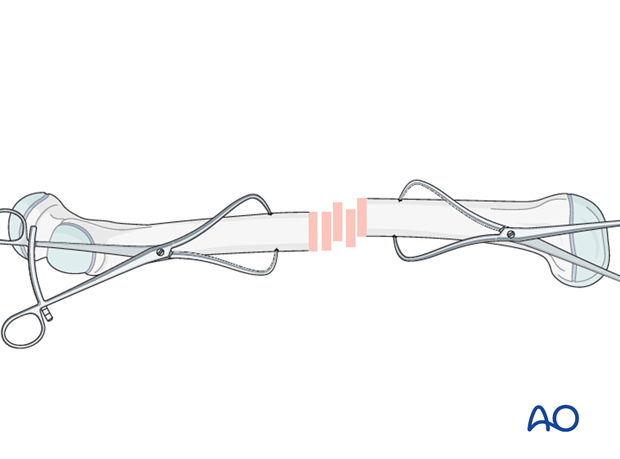

4. Reduction

After extraperiosteal exposure of the lateral aspect of the femur, perform direct reduction using manual traction/traction table, and/or bone reduction forceps.

Anatomical fracture reduction can be observed directly.

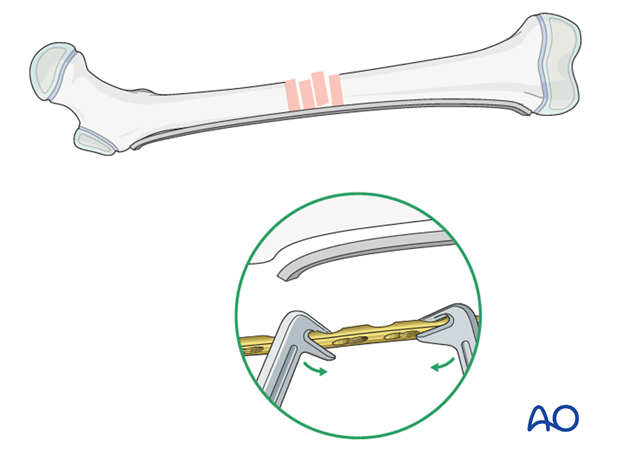

5. Plate contouring

Plate positioning

Position the plate on the lateral aspect of the femur.

Fitting the plate to the bone

Depending on the planned location, proximal and distal contouring of the plate may be necessary.

Contouring is aided by a stable provisional reduction and a malleable template that can be shaped along the bone surface.

The malleable template is then used as a guide for shaping the plate to the bone.

6. Fixation

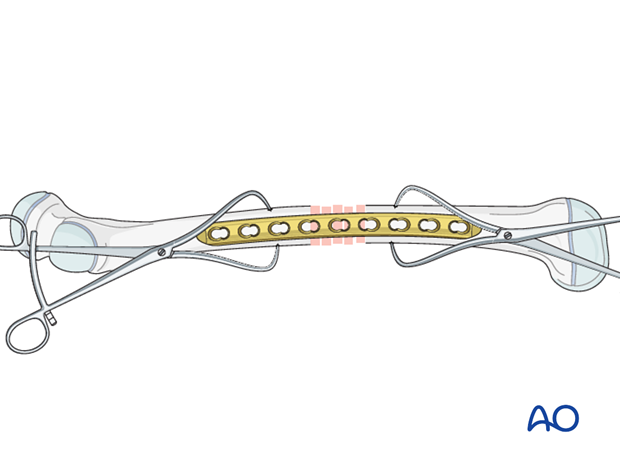

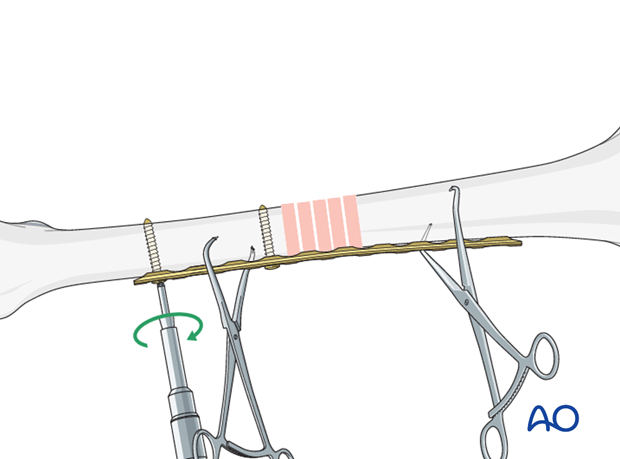

Application of the plate

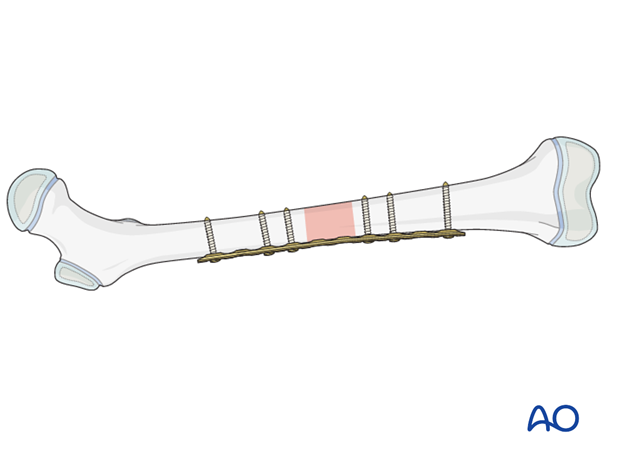

Avoid periosteal stripping when exposing the bone for plate fixation.

Position the plate over the fracture so that at least three holes are available in the proximal and distal fragments.

Screw insertion

Insert the first screw close to the fracture site.

Confirm plate position relative to the fragment before placing the second screw.

Insert the second screw through the plate in the same fragment and tighten both screws.

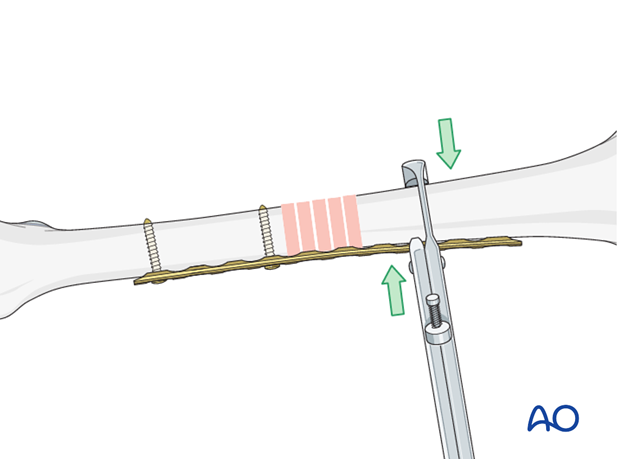

If unstable, fix the plate to one fragment and then reduce the other fragment onto the plate, using a bone holding forceps.

Assessment of rotational alignment

Confirm rotational alignment of the femur clinically and radiographically before fixing the second fragment. This can be done by:

- Direct visualization of fracture site

- Fluoroscopy of fracture site

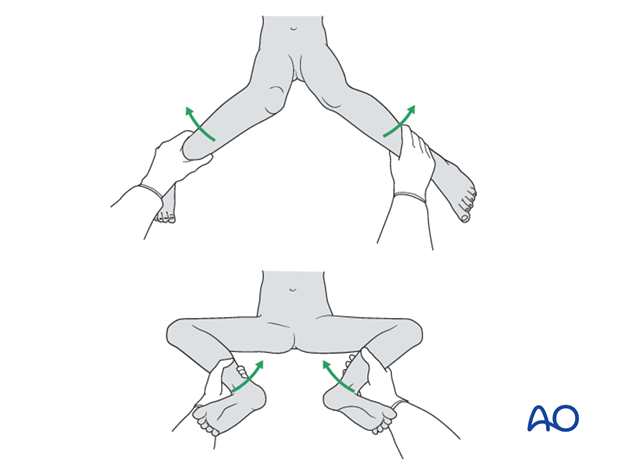

- Comparing internal and external rotation to the contralateral side

- Fluoroscopy of proximal femur (lesser trochanter profile)

For more detail see the additional material on assessment of rotation.

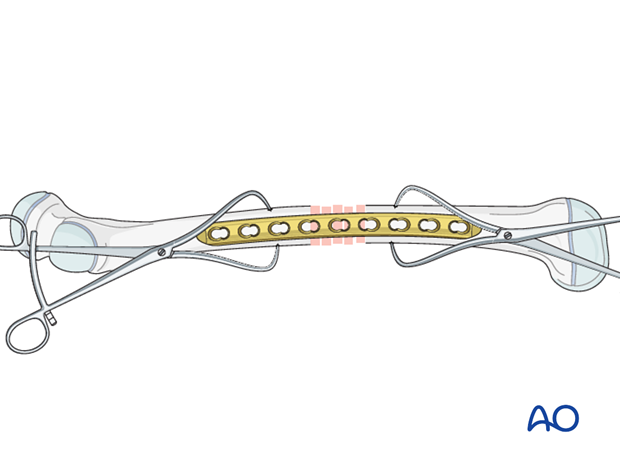

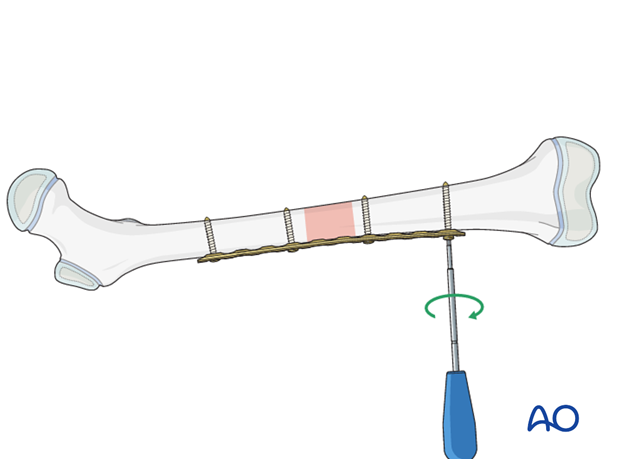

Insertion of screws in other main fragment

Insert the third and fourth screws in the other main fragment.

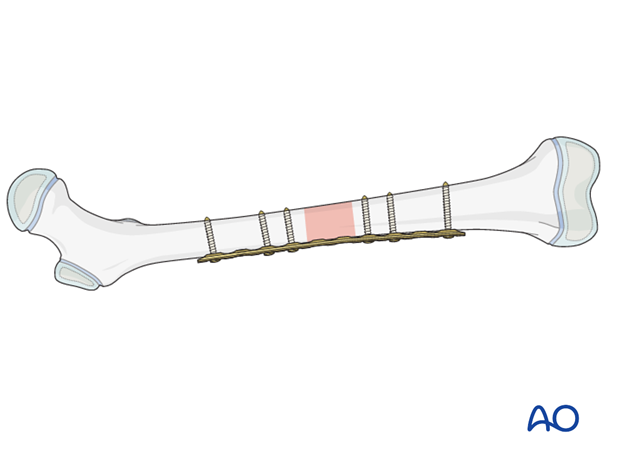

Finalizing plate fixation

Insert the remaining screws so there are three bicortical screws in each fragment.

7. Final assessment

Check the range of internal and external rotation of the leg and compare with the contralateral limb.

Obtain final AP and lateral fluoroscopic views.

8. Aftercare

Immediate postoperative care

The patient should get out of bed and begin ambulation with crutches on the first postoperative day.

In most cases partial weight bearing is permitted until preliminary callus is present at 4–6 weeks.

Analgesia

Routine pain medication is prescribed for 3–5 days postoperatively.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently, to exclude distal neurovascular compromise.

Compartment syndrome, although rare, should be considered in the presence of severe swelling, increasing pain, and changes to neurovascular signs.

Discharge care

Discharge from hospital follows local practice and is usually possible after 1–3 days.

Mobilization

The patient should ambulate with crutches and begin knee range-of-motion exercises.

Follow-up

The patient is usually reviewed 2 weeks after surgery for clinical and radiographic assessment, and wound check.

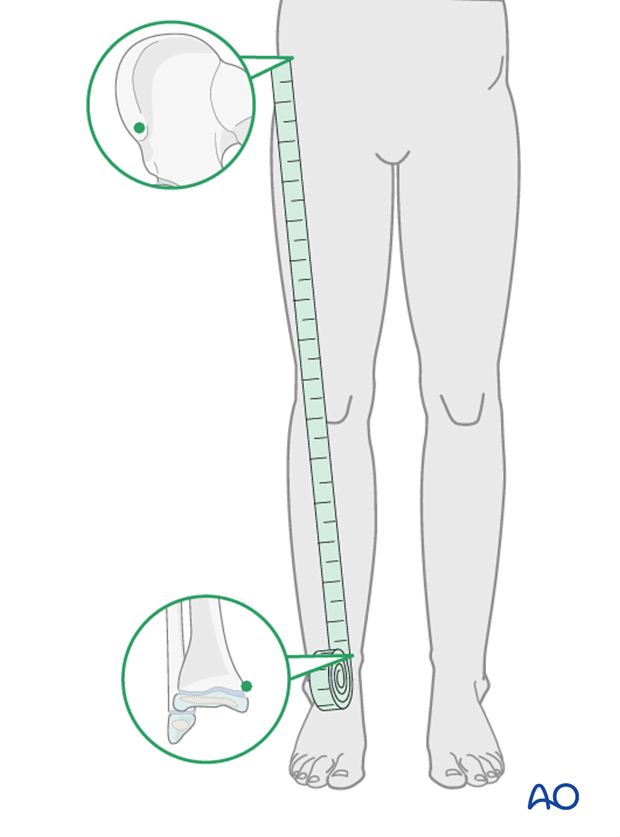

Clinical assessment of leg length and alignment is recommended at one-year.

Clinical assessment of leg length uses a tape measure from the ASIS to the medial malleolus.

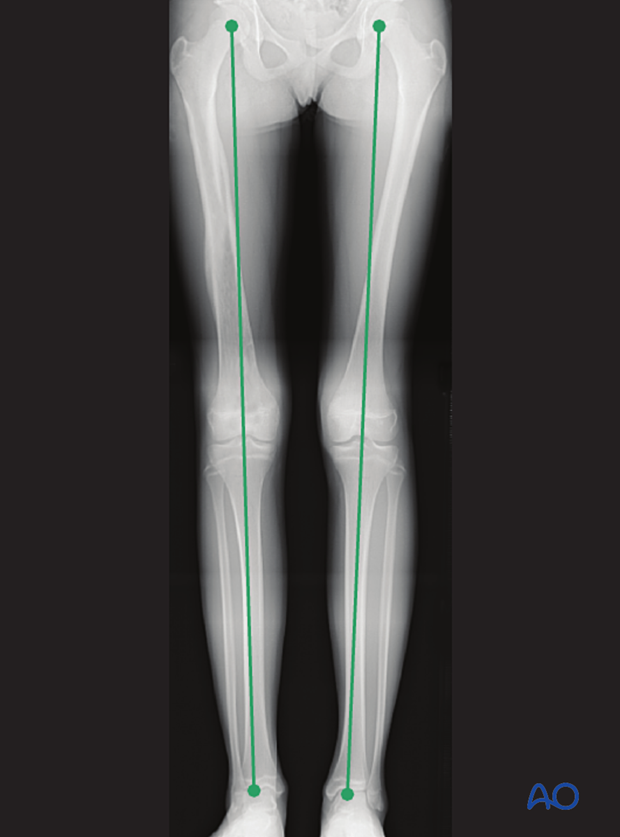

If there is any concern about leg length discrepancy or malalignment, long-leg x-rays are recommended.

Leg length is measured from the femoral head to the ankle joint.

Implant removal

If the patient develops symptoms related to the implant, it can be removed once the fracture is completely healed, usually 6–12 months following injury.