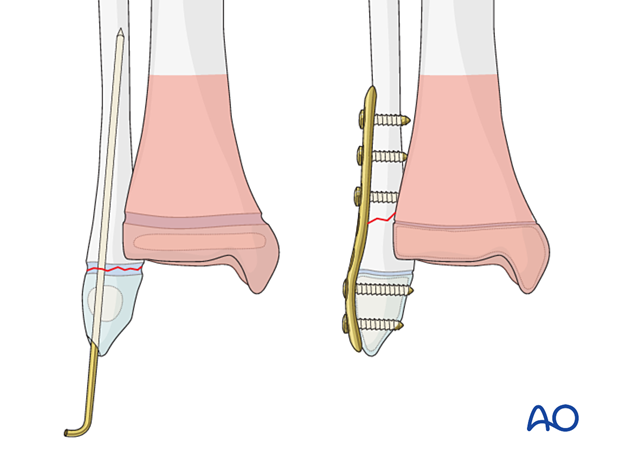

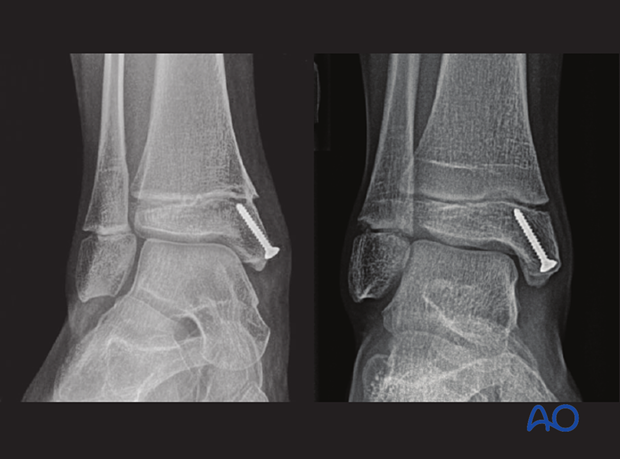

Open reduction; screw fixation

1. General considerations

Introduction

Displaced articular fractures require an open approach with anatomical reduction to restore the articular surface and align the physis.

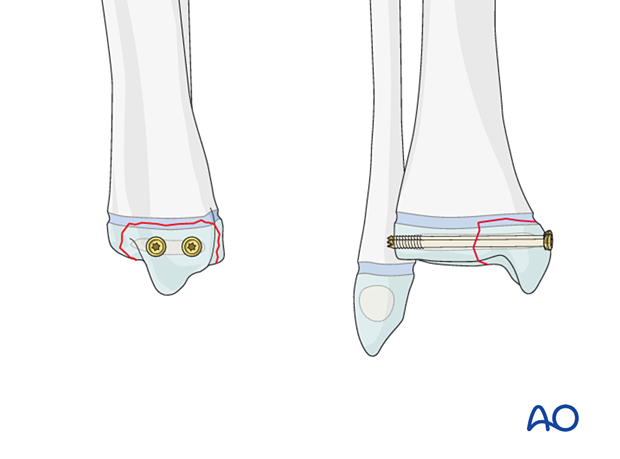

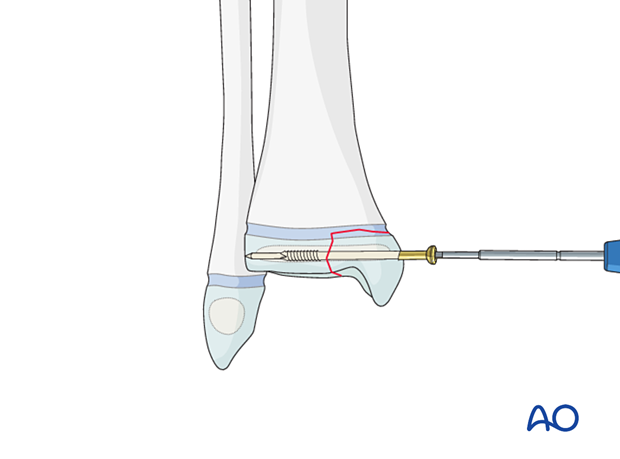

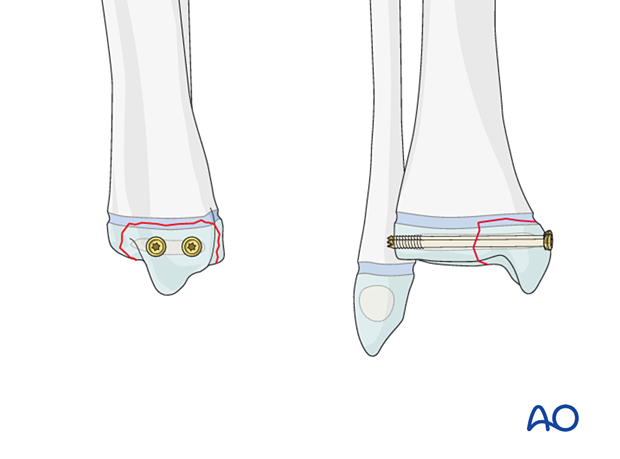

The screw trajectory is typically medial-to-lateral, within the epiphysis and parallel to the physis.

If the fragment is sufficiently large, two screws can be used.

Associated fibular fracture

A fibular fracture often reduces with reduction and fixation of the tibial fracture and does not require separate consideration.

If the alignment and stability of the fibular fracture are unsatisfactory after fixation of the tibial fracture, surgical treatment of the fibular fracture is also required.

If the distal tibial fracture is highly comminuted, fixation of the fibular fracture may add to overall stability.

Associated syndesmotic injury

Proximal tenderness and swelling may indicate an associated syndesmotic injury, which affects ankle joint stability.

After fixation of the primary tibial fracture, assessment of stability is performed by stressing the fibula under image intensification.

If the syndesmosis remains unstable, transfixation is usually required.

Treatment goals

The goal is to maintain anatomical reduction and stability until healing, without additional damage to the physis.

This type of physeal fracture has a high risk of growth disturbance, nonunion, and subsequent osteoarthritis. Anatomical restoration of these fractures reduces these risks.

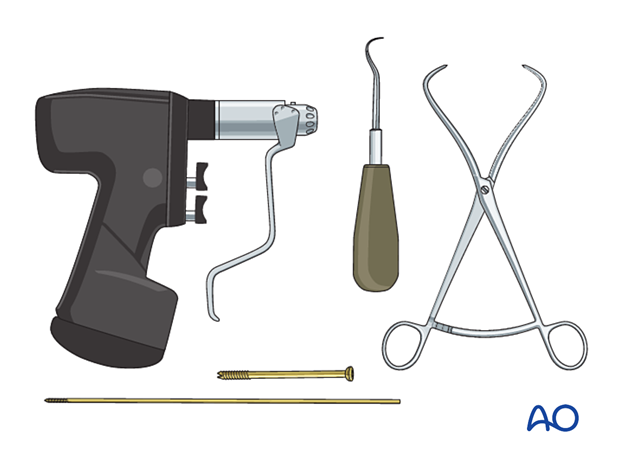

2. Instruments and implants

Appropriately sized cannulated or noncannulated lag screws (2.7, 3.5, or 4.0 mm) can be used.

The following equipment is used:

- Cannulated screw set with guide wire

- Drill

- Image intensifier

- Reduction forceps

- Dental pick or hook

3. Patient preparation and approach

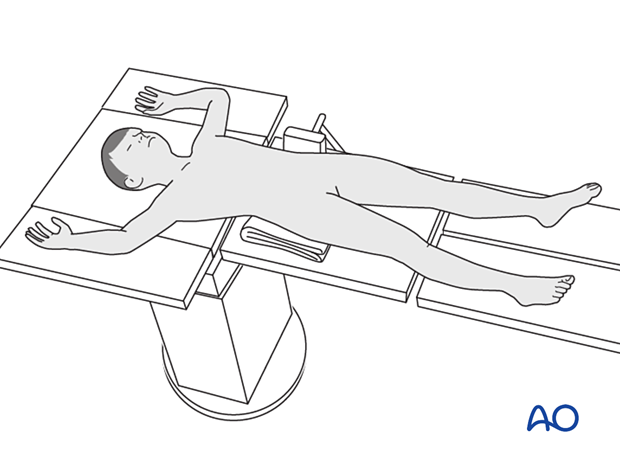

Patient positioning

Place the patient in a supine position on a radiolucent table.

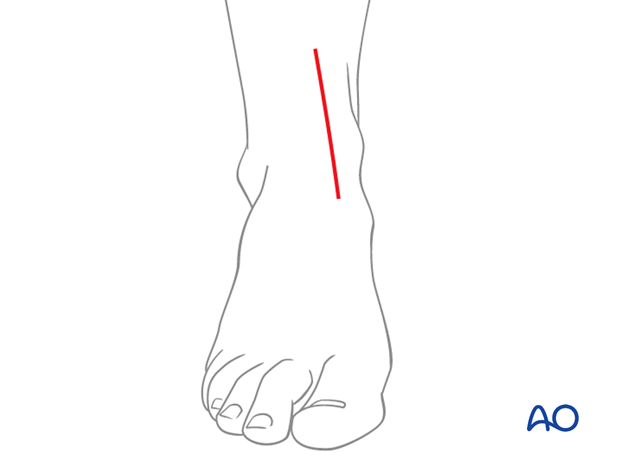

Approach

These fractures are typically treated through an anteromedial approach to remove any block to reduction and stabilize the fracture.

4. Reduction

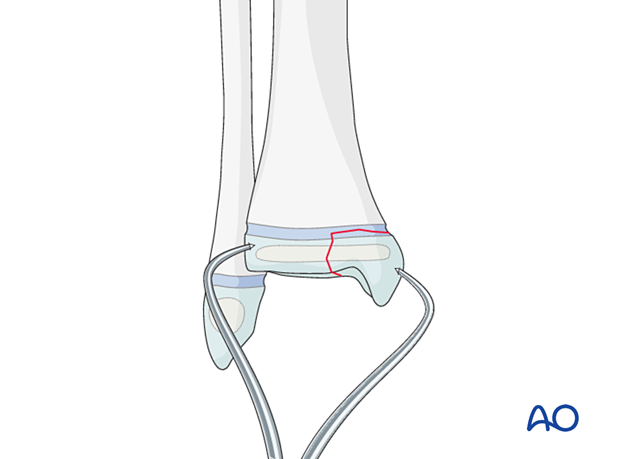

Remove blood clots, loose fragments, soft callus, and entrapped periosteum.

Reduce the fracture with gentle manipulation, a dental pick, or K-wire.

Hold the reduction with reduction forceps.

Confirm anatomical reduction of the articular surface under direct vision.

5. Fixation

Insert a lag screw parallel to the physis in a standard manner.

The reduction is performed through the anteromedial incision. The guide wires and screws, however, may be inserted percutaneously.

If the fragment is sufficiently large, two screws can be used.

6. Fibular fracture management

Most fibular fractures do not require treatment. Indications for fixation include:

- Augmentation of the stability of tibial fracture fixation

- Significant displacement of the fibular fracture

The type of fracture pattern dictates the method of fixation of the fibular fracture.

In a younger child, these fractures may be fixed with K-wires in a standard manner. Multiple passes of the K-wire through the physis should be avoided.

In an older patient with a closing physis, these fractures may require plate fixation.

If screws are inserted on both sides of the physis, compression should be avoided and the periosteum and perichondral ring not be disturbed. To protect the perichondral ring, a dissector or elevator may be used to offset the plate during screw insertion. The plate should be removed soon after the fracture has healed.

7. Assessment of the syndesmotic complex

After appropriately stabilizing the tibial fracture, check the stability and reduction of the syndesmotic complex.

Assess AP and lateral translation of the fibula by stressing the ankle joint with a combination of lateral translation and external rotation with an image intensifier. If there is evidence of instability, stabilization of the syndesmosis may be necessary.

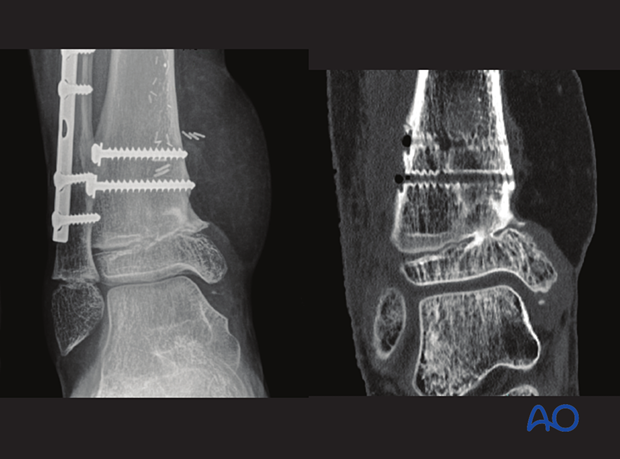

8. Final assessment

Recheck the fracture alignment and implant position clinically and with an image intensifier before anesthesia is reversed.

Confirm stability of the fixation by moving the ankle through a range of dorsi/plantar flexion.

9. Immobilization

A molded below-knee cast or fixed ankle boot is recommended for a period of 2–6 weeks as the strength of fixation may not provide sufficient stability for unrestricted weight bearing.

10. Aftercare

General considerations

Weight-bearing status for these fractures is based on local protocol and should consider the severity of soft-tissue injury and stability of fixation.

Pain control

Patients tend to be more comfortable if the limb is splinted.

Routine pain medication is prescribed for 3–5 days after surgery.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently to exclude neurovascular compromise or evolving compartment syndrome.

Discharge care

Discharge follows local practice and is usually possible within 48 hours.

Follow-up

The first clinical and radiological follow-up is usually undertaken 5–7 days after surgery to check the wound and confirm that reduction has been maintained.

Cast removal

A cast or boot can be removed 2–6 weeks after injury.

Mobilization

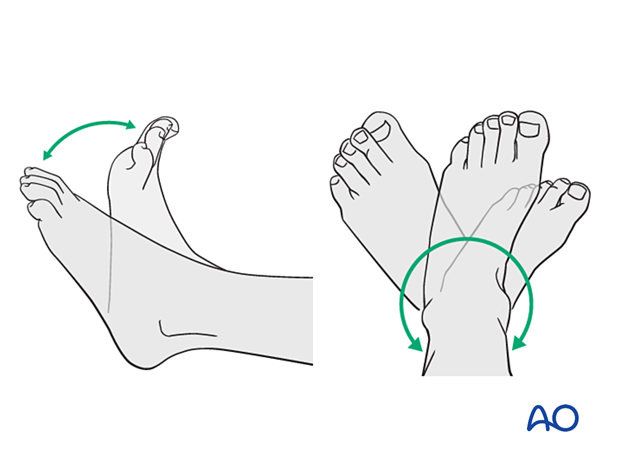

After cast removal, graduated weight-bearing is usually possible.

Patients are encouraged to start range-of-motion exercises. Physiotherapy supervision may be required in some cases but is not mandatory.

Sports and activities that involve running and jumping are not recommended until full recovery of local symptoms.

Implant removal

Implant removal is not mandatory and requires a risk-benefit discussion with patient and carers.

Follow-up for growth disturbance

All patients with distal tibial physeal fractures should have continued clinical and radiological follow-up to identify signs of growth disturbance.

Compare alignment and length clinically with the uninjured leg.

A Harris growth arrest line, parallel to the physis, is radiological evidence of continuation of normal growth.

Recommended reading:

- Nguyen JC, Markhardt BK, Merrow AC, et al. Imaging of Pediatric Growth Plate Disturbances. Radiographics. 2017 Oct;37(6):1791–1812.

Parallel Harris growth arrest line in the distal tibia of a 10-year-old patient, 6 months after injury (right image) excluding a physeal injury

Growth disturbance (convergent Harris growth arrest lines) of an open Salter-Harris II fracture of the distal tibia in a 10-year-old patient, 6 months after injury