External fixation

1. General considerations

Principles of modular external fixation

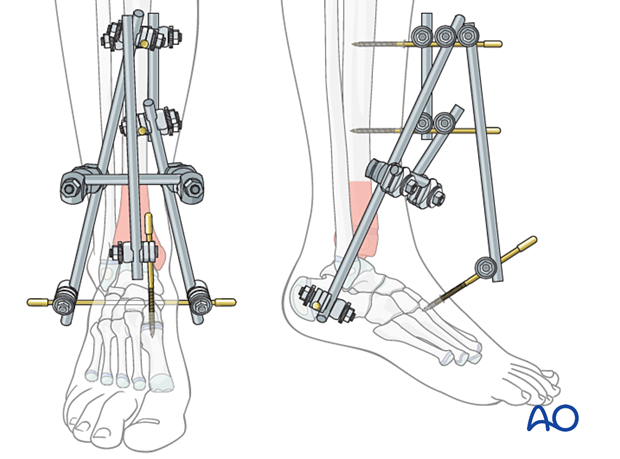

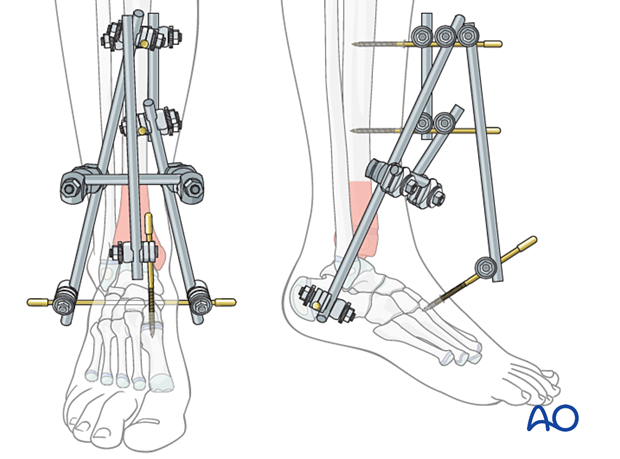

A joint-spanning external fixator may be necessary for distal tibial fractures with severe soft-tissue injury.

It is applied to the tibia and the foot, avoiding the zone of injury. The construct should not impede soft-tissue care and planned implant placement.

A triangular construct provides more stability than a simple monolateral fixator. A circular construct may provide additional stability in heavier or older patients. This may also be an option for definitive treatment.

Details of external fixation in children are described in:

Specific considerations for the distal tibia are given below.

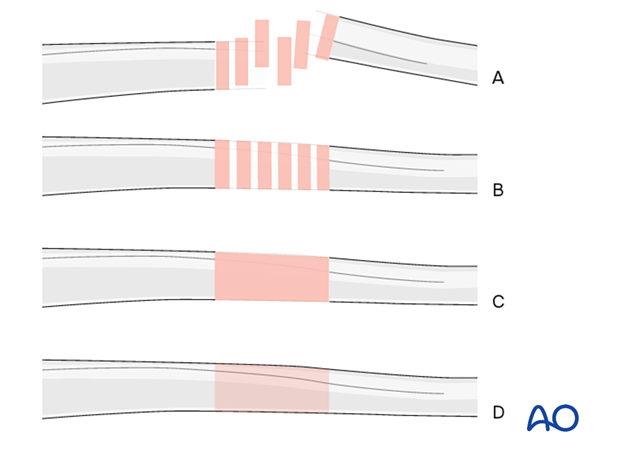

Throughout this section, generic fracture patterns are illustrated as:

- Unreduced

- Reduced

- Reduced and provisionally stabilized

- Definitively stabilized

Pin size in tibial fractures

External fixation is suitable for all ages, but the pin diameter must be appropriate to the size of the bone.

Pins with a 3.0–5.0 mm thread diameter are suitable for tibial fractures and should typically be between ¼ and ⅓ of the external bone diameter.

2. Patient preparation

Place the patient in a supine position on a radiolucent table with a block under the heel.

3. Pin insertion

Safe pin placement

Use safe zones for pin placement.

Avoid inserting pins into a physis.

Pin placement in the tibia

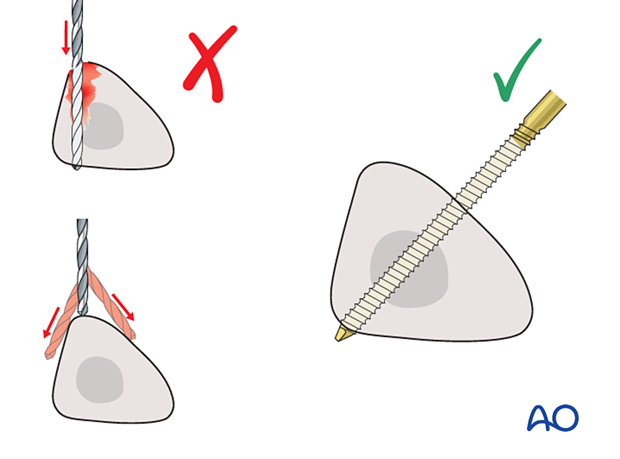

Drilling a hole in the thick tibial crest may be associated with excessive heat generation.

There is also a risk that the drill bit may slip medially or laterally, damaging the soft tissues.

As the anteromedial tibial surface provides adequate thickness for placement of pins, this trajectory is preferable.

A trajectory 20°–60° relative to the sagittal plane for the proximal tibial shaft and 30°–90° for the distal tibial shaft is recommended.

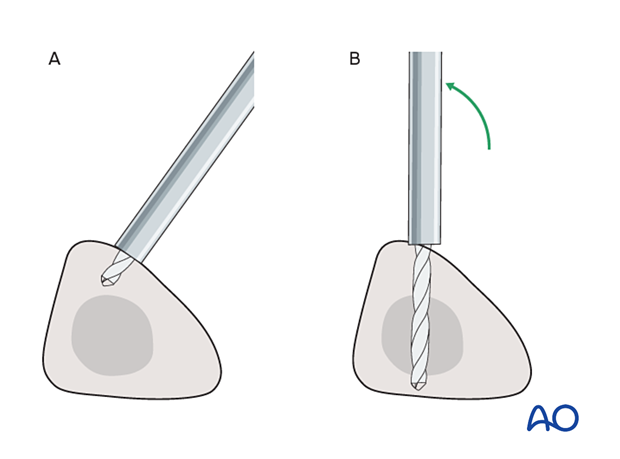

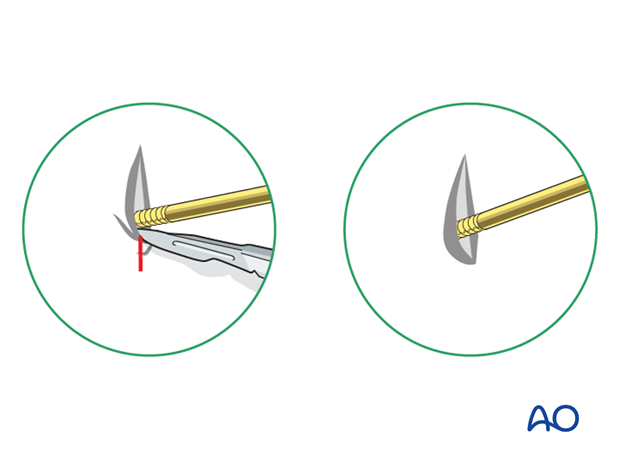

To avoid the fixator catching on the opposite leg, the pins may be placed more anteriorly. The drill bit is initially positioned with the tip just medial to the anterior crest and with the drill bit perpendicular to the anteromedial surface (A).

As the drill bit starts to penetrate the surface, the drill is gradually moved more anteriorly until the drill bit is in the desired plane (B).

This should prevent the tip from sliding down the medial or lateral surface.

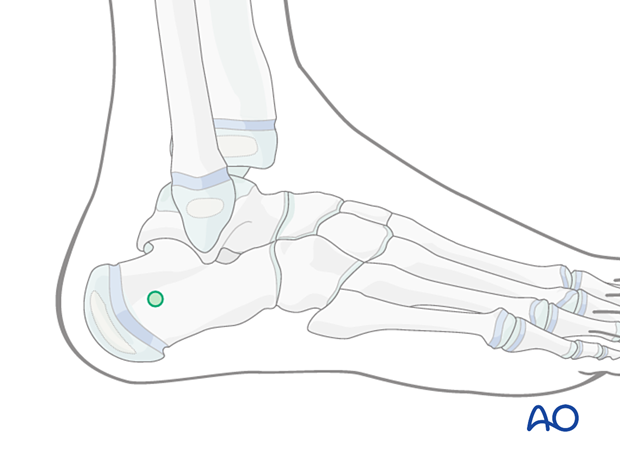

Pin placement in the ankle and/or foot

For the construction of the foot frame, a pin is placed in the calcaneus (green circle).

Use an image intensifier to avoid the calcaneal apophysis.

In larger children, the base of the fifth metatarsal may be used to place an additional pin.

4. Frame construction for triangular external fixation

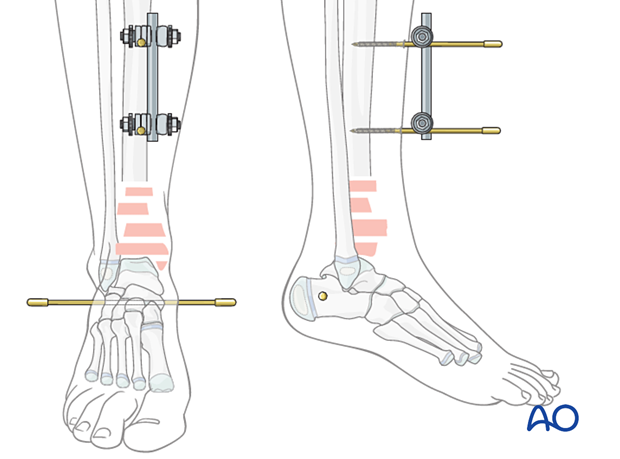

Construction of tibial frame and insertion of Steinmann pin

Insert two anterior pins slightly medial to the tibial crest, outside the zone of injury. Place the pins far enough apart to ensure adequate stability.

Connect the pins with a short rod and tighten the rod-to-pin clamps. More proximal placement facilitates later definitive open fixation and avoids damaged soft tissue in the fracture zone.

Insert a Steinmann or threaded pin from medial to lateral through the calcaneus. Avoid damage to the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle and the posterior calcaneal apophysis.

Tibiocalcaneal connection

Connect each end of the calcaneal pin to one of the tibial pins with a rod using rod-to-pin clamps. These are initially applied loosely to facilitate fracture reduction.

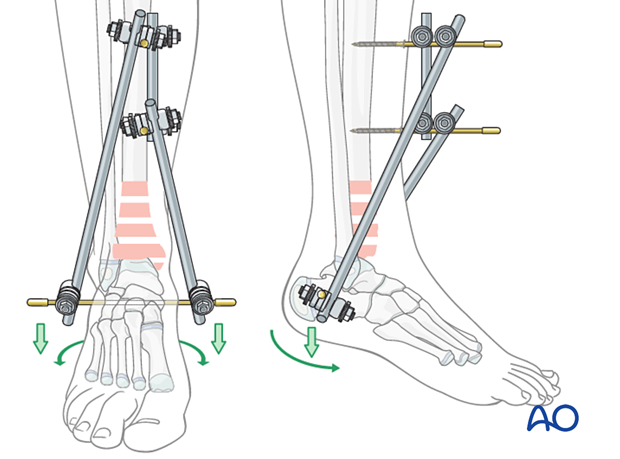

5. Reduction and fixation

Reduction

Reduce the fracture using the external fixator as a reduction device. Confirm reduction with an image intensifier, and tighten all clamps.

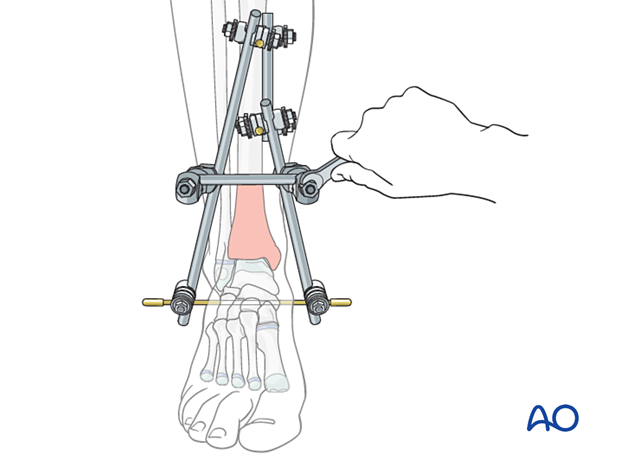

Connecting the rods

The two tibiocalcaneal rods may be connected with a short rod using rod-to-rod clamps to stabilize the construct.

Tibiotarsal transfixation

Insert one or two small pins to keep the midfoot in a neutral position in the:

- First metatarsal

- First and fifth metatarsal

They are connected to the tibial frame, avoiding the physis.

6. Pin sites

Release tethered skin around the pins by extending the incision.

Dress the pin sites to prevent skin motion and therefore reduce the risk of infection.

7. Final assessment

Check pin placement and fracture alignment with an image intensifier before anesthesia is reversed.

Use clinical examination to check lower extremity alignment and rotation.

8. Aftercare

Pin-site care

Pin-care protocolThere is no universally agreed protocol for pin-site care.

The following points are, however, recommended:

- Pin-site care should continue until removal of the external fixator.

- The pin sites should be kept clean.

- Crusts or exudates should be removed.

- The pins may be cleaned with water, saline, a disinfectant solution, or alcohol. The frequency of cleaning varies from daily to weekly.

- Ointments or antibiotic solutions are not recommended for routine pin-site care.

- Pin sites do not need to be protected while showering or bathing with clean water but should be dried immediately.

Initial management is with oral anti-staphylococcal antibiotics.

In case of pin loosening or unresponsive pin site infection, the following steps should be taken:

- Remove all involved pins and place new pins in a healthy location.

- Debride the pin sites in the operating theater, using curettage and irrigation.

- Take specimens for microbiological culture to guide appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Internal fixation following an infected external fixator pin has a higher risk of infection and should be avoided unless no reasonable alternative is available.

Pain control

Routine pain medication is prescribed for 3–5 days after injury if necessary.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently to exclude neurovascular compromise or evolving compartment syndrome.

Discharge care

Discharge follows local practice and is usually possible within 48 hours.

Mobilization

The patient should be encouraged to move the hip and ankle within the limits of comfort.

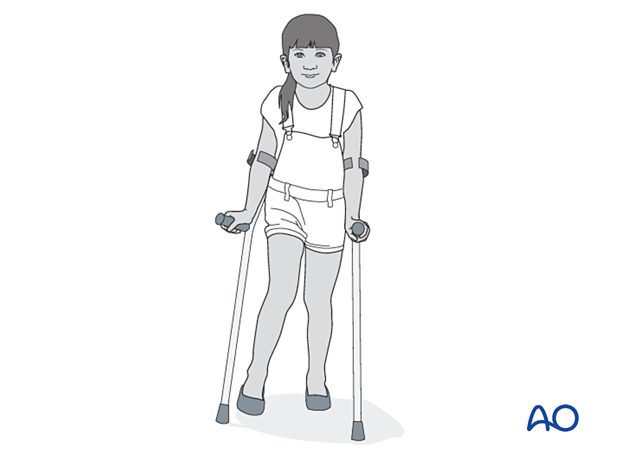

In most cases, the fixator is not sufficiently stable to allow initial weight-bearing. Partial weight-bearing can begin when callus is visible, typically at 4 weeks.

Follow-up

The patient should be seen 5–7 days after surgery to check the pin sites.

X-rays are taken to check stability and alignment.

Fixator removal

Fixator removal is determined by the age of the child and the healing rate.

Look for mature callus bridging 3 or 4 cortices of the tibia before removing the fixator.

Refracture is a common complication, and many surgeons recommend partial weight-bearing with crutches after fixator removal to allow further strengthening of the callus.

Follow-up for growth disturbance

All patients with distal tibial physeal fractures should have continued clinical and radiological follow-up to identify signs of growth disturbance.

Compare alignment and length clinically with the uninjured leg.

A Harris growth arrest line, parallel to the physis, is radiological evidence of continuation of normal growth.

Recommended reading:

- Nguyen JC, Markhardt BK, Merrow AC, et al. Imaging of Pediatric Growth Plate Disturbances. Radiographics. 2017 Oct;37(6):1791–1812.