Open reduction; plate fixation

1. General considerations

Introduction

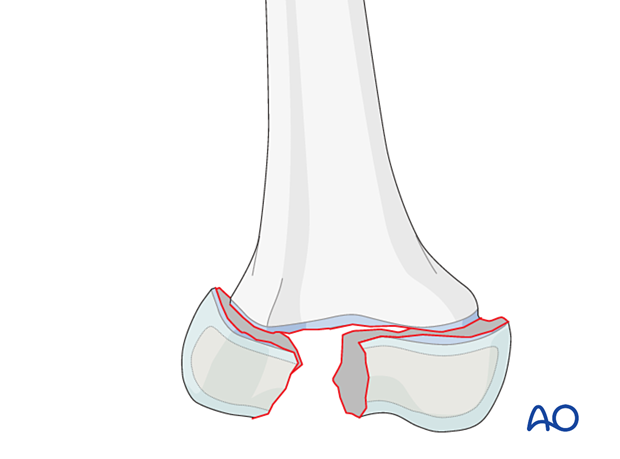

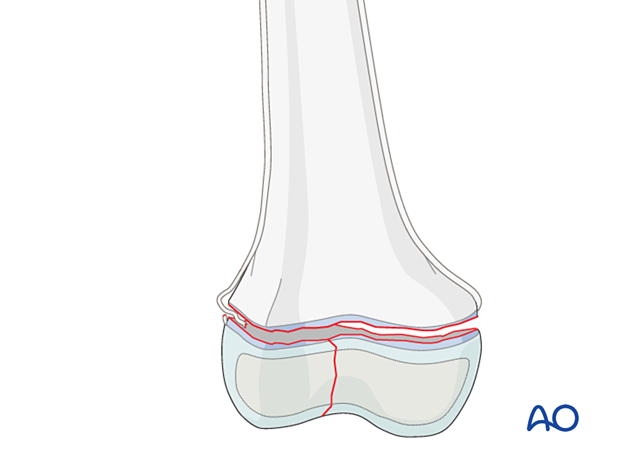

A multifragmentary SH III fracture may require a combined approach using a screw to achieve anatomical reconstruction of the joint and plating for stabilization of the epiphysis to the metaphysis.

This technique crosses the distal femoral physis and will sacrifice remaining growth and therefore is only recommended if there is minimal growth remaining or if there is severe comminution of the growth plate.

Treatment goals for SH III fractures

The main goals of treatment of these fractures are:

- Restore joint congruity

- Uncomplicated healing

- No secondary displacement

- Minimize injury to the growth plate

Distal femoral physeal fractures are associated with a high rate (30–50%) of growth arrest.

Open reduction

These fractures are often displaced and require open reduction to restore the articular surface. Reduction can be approached through a medial or lateral parapatellar incision, depending on the fracture anatomy.

A plate is usually placed laterally but a medial approach may be more suitable for articular fracture on the medial aspect of the epiphysis.

If there is instability across the growth plate, the epiphysis may be stabilized to the metaphysis with either K-wires or plate fixation in older children.

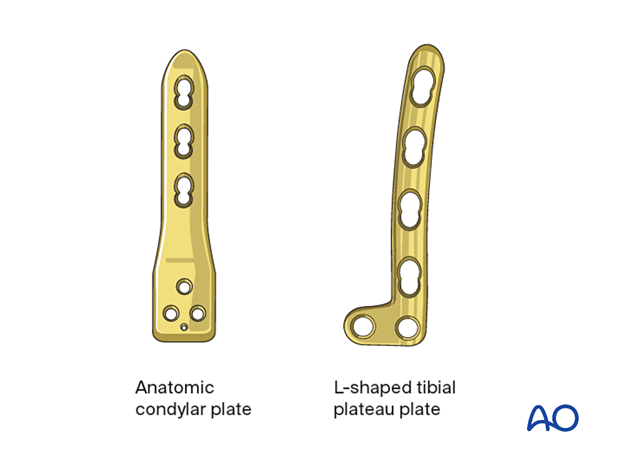

Size and type of implant

The size and type of implant are determined by the size and age of the patient as well as by the fracture pattern. The range of plate sizes in pediatric femur fractures is between 2.7 and 5.0 mm.

Pediatric anatomic condylar plates are available and adult anatomic plates may be appropriate for older patients. This is particularly relevant to patients with a closing growth plate or, in rare cases, where a stable fracture fixation requires sacrificing and bridging of the growth plate. The L-shaped tibial plateau plate fits very well on the contralateral distal femur and allows at least two screws in the distal fragment.

2. Patient preparation and approach

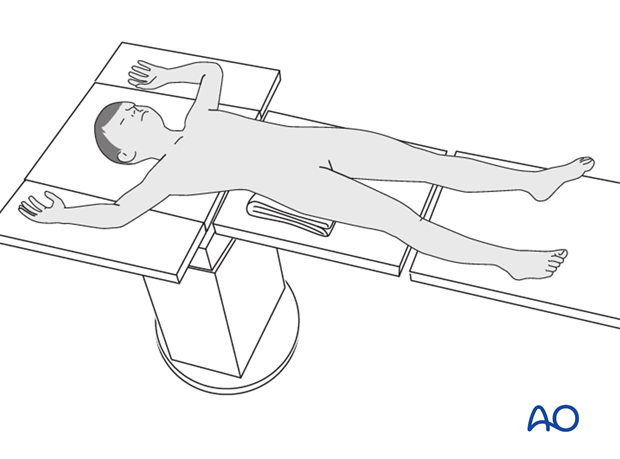

Patient positioning

Place the patient supine on a radiolucent table with a C-arm.

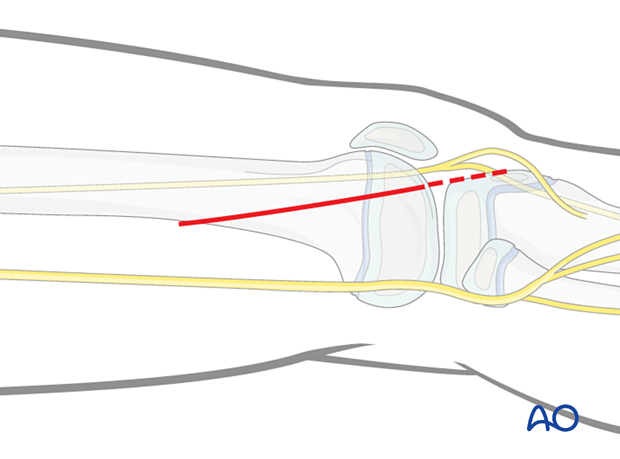

Approach

The majority of the fractures are approached using the distal component of a direct lateral approach (or medial approach if necessary).

3. Reduction and temporary fixation of the articular fracture

Removal of impediments

It may be necessary to remove interposed soft-tissue and periosteum prior to reduction of the fracture under direct vision.

Reduction

Reduce and hold the epiphyseal fracture with forceps. Insert a K-wire in the epiphysis parallel to the growth plate to temporarily stabilize the fracture. Application of forceps or K-wire may require a separate stab incision.

Confirm anatomical reduction by direct visualization or image intensification.

4. Option: screw fixation of articular fracture

Planning for additional screw

The epiphyseal fracture may be stabilized with an additional screw, especially if a straight plate is selected. Interfragmentary compression can be achieved with a bone clamp, a partially threaded cancellous screw or a lag screw.

This screw should be placed to not interfere with the planned plate placement.

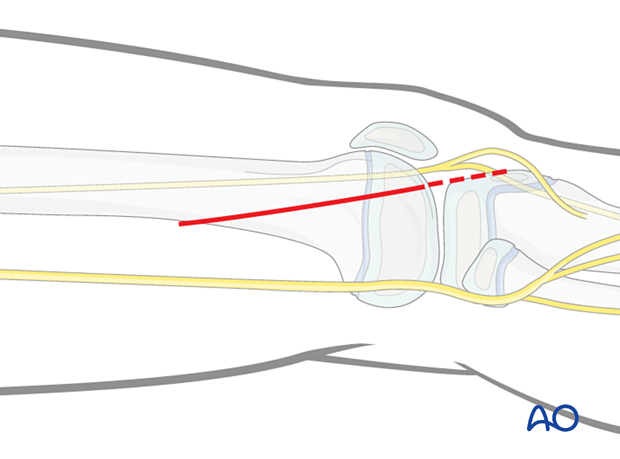

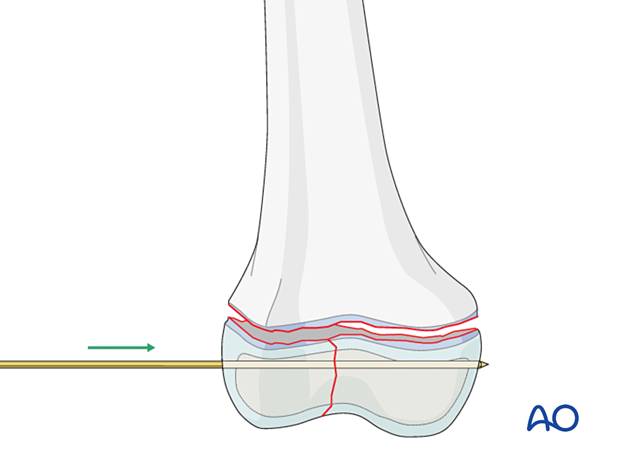

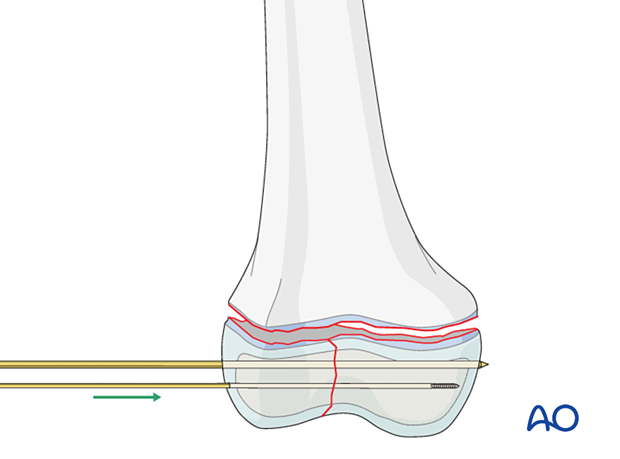

Insertion of guide wire

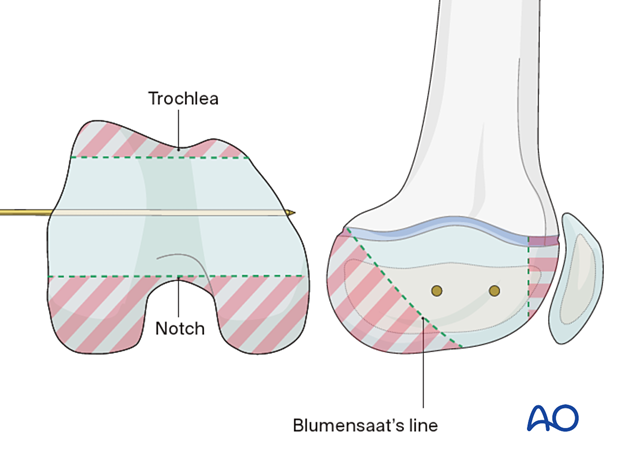

Insert a guide wire in the epiphysis parallel to and away from the growth plate.

If the K-wire for temporary fixation is in an ideal position for the screw this can be used instead.

Epiphyseal screw insertion

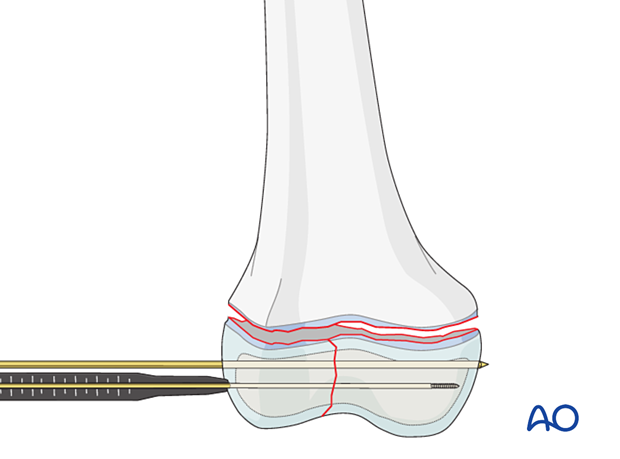

Determine the appropriate screw length.

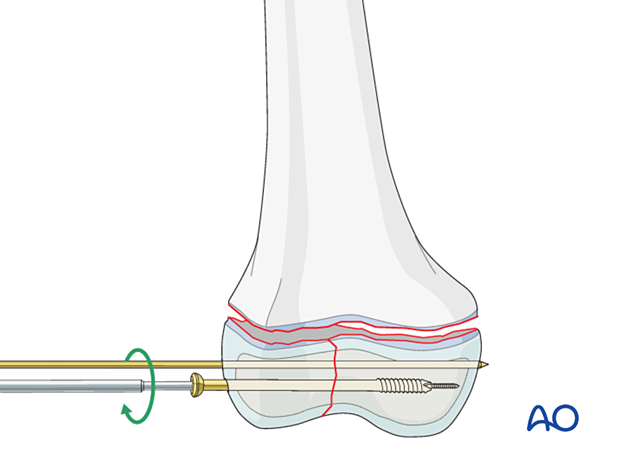

Choose a partially threaded screw ensuring that the thread will not cross the fracture.

Insert the screw and compress the fracture.

Confirm anatomical reduction and fixation of the articular surface with image intensification.

Remove the temporary K-wire.

5. Reduction and temporary fixation of growth plate

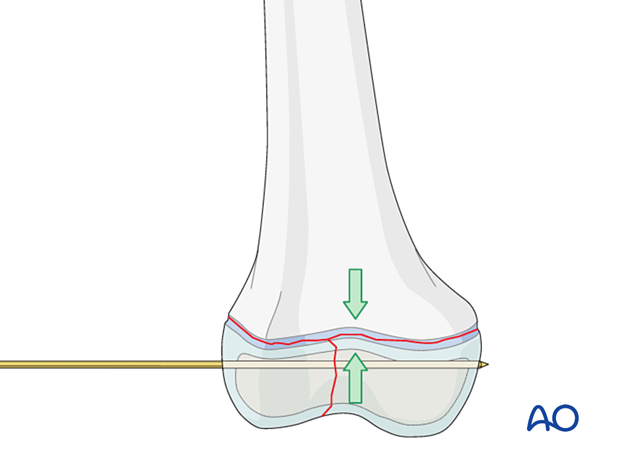

Reduction

Reduce the growth plate under direct vision.

Extend the incision if there is a block to reduction (eg periosteum).

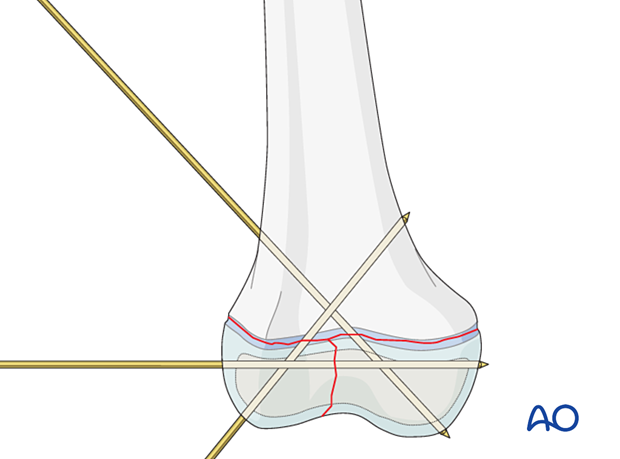

Temporary fixation with K-wires

Once the epiphysis is anatomically reduced on to the metaphysis, insert two K-wires through the fracture for temporary fixation.

The K-wires should be placed so they do not interfere with later plate application.

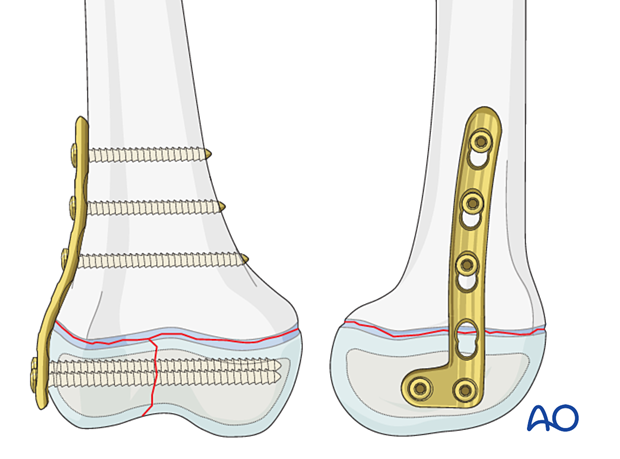

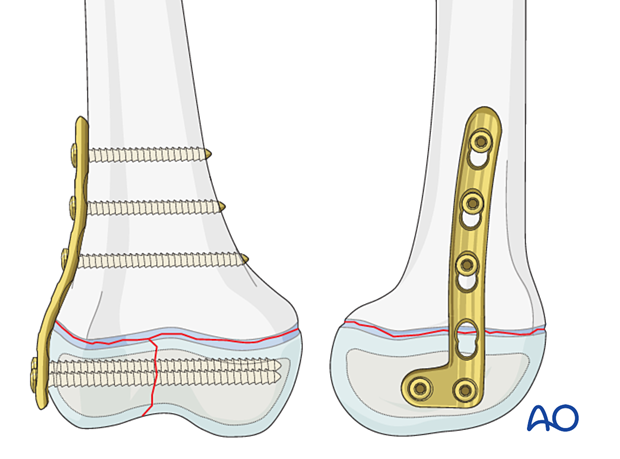

6. Plate fixation

Plate placement and screw insertion

Plate contouring is often required to match the anatomy of the femur.

Interfragmentary compression of the articular fracture can be achieved with a bone clamp, a partially threaded cancellous screw or a lag screw.

Prior to screw insertion check the femoral alignment with image intensification and make sure that both ends of the plate are well aligned and have good contact with the bone.

Start with insertion of a screw on both ends of the plate and then insert further screws.

Insert one or two screws through the plate distal to the growth plate.

Insert two or three screws through the plate proximal to the fracture zone.

7. Final assessment

Check implant position and fracture reduction with image intensification.

Use clinical examination to check lower extremity alignment.

8. Aftercare

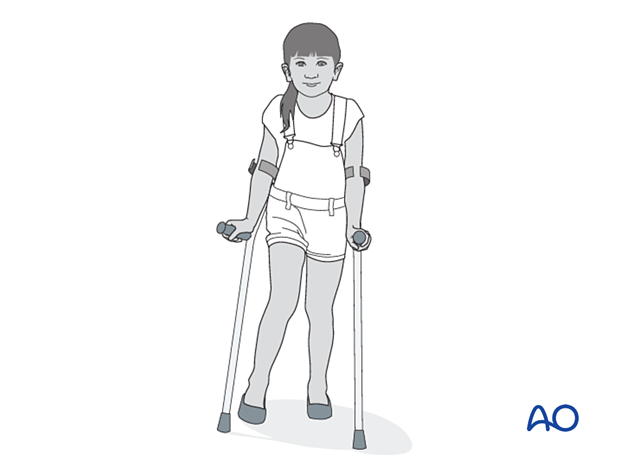

Immediate postoperative care

The patient should get out of bed and begin ambulation with crutches on the first postoperative day.

In most cases the postoperative protocol will be touch-weight bearing for the first 4 weeks.

Analgesia

Routine pain medication is prescribed for 3–5 days postoperatively.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently to exclude neurovascular compromise, particularly following displaced, high-energy fractures, when deterioration may be delayed.

Compartment syndrome, although rare, should be considered in the presence of severe swelling, increasing pain, and changes to neurovascular signs.

Discharge care

Discharge from hospital follows local practice and is usually possible after 1–3 days.

Mobilization

The patient should continue ambulation with crutches.

After ORIF, fractures are sufficiently stable for the knee to be immobilized in a removable brace and range-of-motion exercises can begin early in the postoperative phase.

For the more unstable or comminuted fractures, range-of-motion exercises will begin at a slower rate.

Follow-up

Clinical and radiological follow-up is usually undertaken 2 weeks postoperatively.

Follow-up for leg-length discrepancy

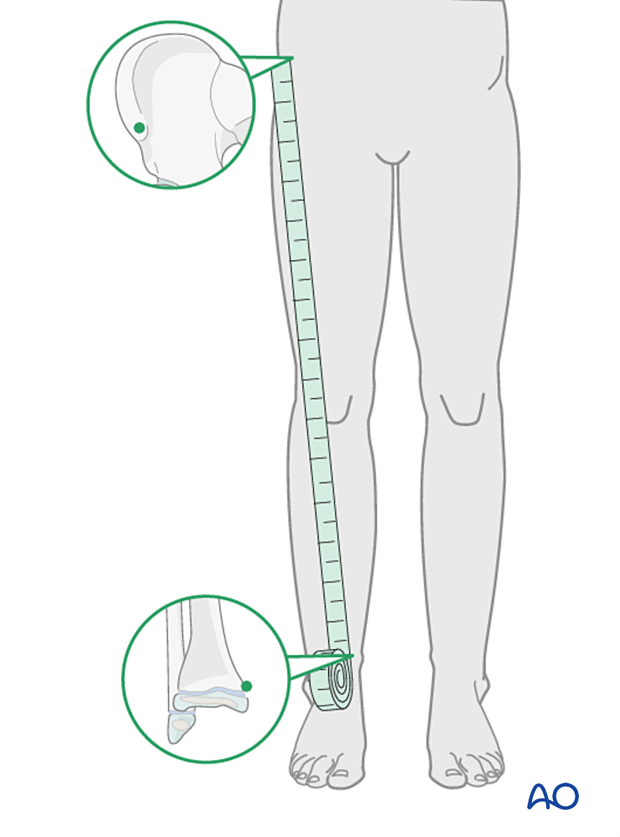

Clinical assessment of leg length and alignment is recommended yearly until skeletal maturity.

Clinical assessment of leg length uses a tape measure from the ASIS to the medial malleolus.

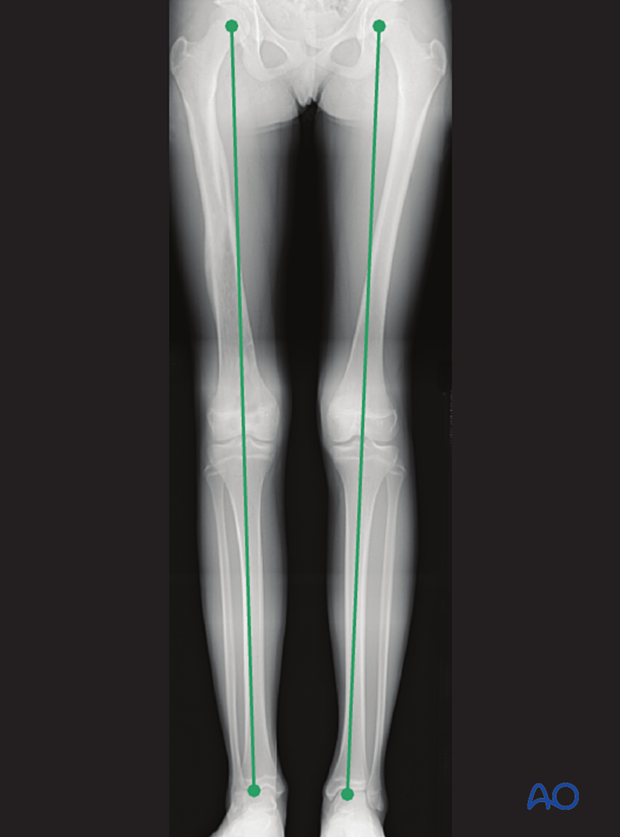

If there is any concern about leg length discrepancy or malalignment, long leg x-rays are recommended.

Leg length is measured from the femoral head to the ankle joint.

If the expected leg length discrepancy if greater then 2 cm additional surgery to correct the leg length may be necessary.

Implant removal

If symptoms develop, plate and screws can be removed once the fracture is completely healed, usually 6–12 months postoperatively.

If K-wires are used, they are typically removed after 4–6 weeks.