Prevention of infection

1. Introduction

All surgical procedures carry risks of infection. Thus, every operation must include all appropriate measures to reduce these risks.

The initial consideration is whether the benefits of surgery justify an open procedure instead of nonoperative treatment. Many closed fractures can be successfully treated without surgery, or with less extensive procedures.

As well as with standard aseptic surgical practices, several specific measures should be taken to reduce the risk of infection in fracture surgery:

- Perioperative antibiotics

- Nutritional support

- Temperature control

- Soft-tissue care: preservation of blood supply, hemostasis, debridement, tension-free wound closure

For more details see a synopsis of the following article:

Alexander JW, Solomkin JS, Edwards MJ. Updated recommendations for control of surgical site infections. Annals of Surgery. 2011 Jun;253(6):1082–93.

2. Closed fractures

If the anticipated outcome of nonoperative treatment for a given fracture is poor and the surgeon selects operative treatment, then appropriate preventive measures must be taken. For all fracture surgery involving internal fixation, as well as exposure of the fracture site, perioperative antibiotics should be administered prior to incision, as they are an accepted means of reducing the risk of infection.

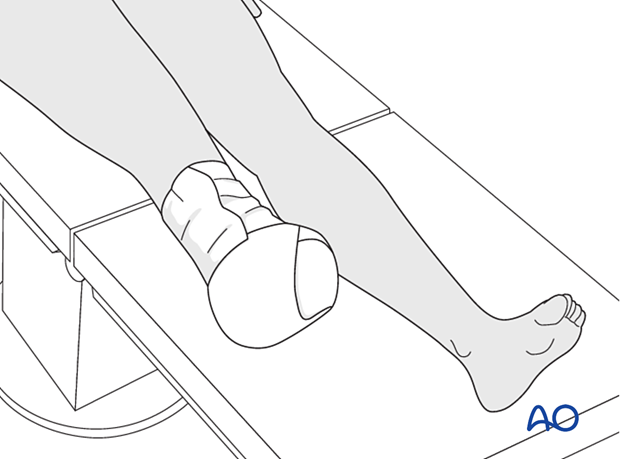

In some cases, surgery should be delayed, or modified, to address metabolic/physiologic abnormalities. In some cases, a less invasive initial treatment might be chosen. For example, temporary external fixation prior to performing open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of a tibial pilon fracture (eg, 43C) with significant soft tissue swelling is known to decrease the risk of infection compared to performing immediate open reduction and internal fixation.

Lengthy operations increase the risk of infection. Preoperative planning helps the surgeon estimate surgical time and identify ways of minimizing the duration of the procedure.

Intraoperative homeostasis (control of temperature and blood sugar, providing transfusion, if necessary, etc.) and postoperative support (eg, nutrition) are other valuable ways of reducing the incidence of infection.

3. Open fractures

Open fractures need the following:

- Prompt diagnosis

- Appropriate intravenous antibiotics

- Meticulous debridement

- Fracture stabilization

- Early wound closure after adequate debridement

Intravenous antibiotics for open fractures

Bacterial contamination is almost always present with open fractures. Bacterial count, and infection rate, can be significantly reduced by prompt administration of intravenous antibiotics. Most infecting bacteria, except in very dirty wounds, are typical skin flora. A first-generation cephalosporin (eg, cefazolin) 1–2 grams/8 hours) is often used, except for patients with a penicillin allergy. For more severe open fracture wounds, add an aminoglycoside (eg, gentamycin 80 mg/8–12 hours) to cover Gram negative bacteria. If significant contamination is present (such as with soil), antibiotics that cover facultative anaerobes, such as high-dose IV penicillin, is usually added (eg, 5–10 million units/24 hours).

Antibiotics for open fractures are an adjunct to debridement. They should begin as soon as the open fracture is diagnosed but need to be continued for only 2–3 days once definitive wound closure has occurred.

Debridement of open fractures

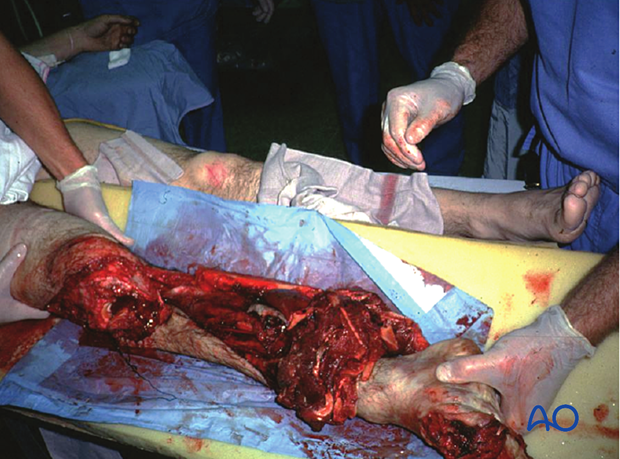

Debridement must be complete, thorough, and aggressive.

Surgical debridement is the most important part of treating an open fracture. During debridement, the surgical site should be thoroughly irrigated (using several liters of normal saline) to reduce the bacterial population.

In cases with significant amounts of dead, or possibly ischemic, tissue, reoperation within 24 to 48 hours for additional debridement may be necessary.

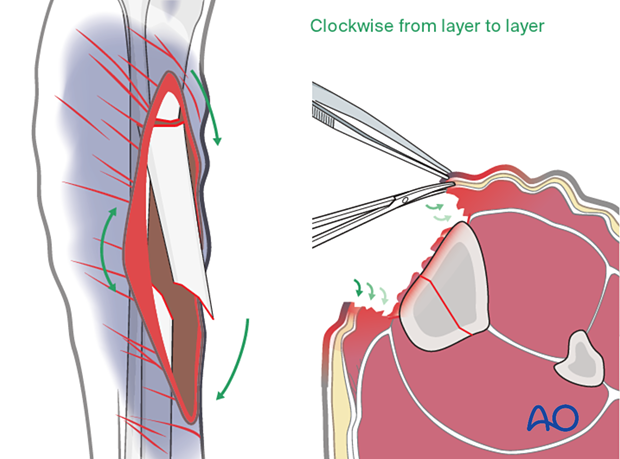

Debridement technique

Deciding what tissue to remove and what to retain is the essential challenge of debridement. This is best learned in the operating room from senior surgeons, and through practice. Typical errors are failure to remove enough compromised tissue or doing so in a way that injures what remains.

Take an organized approach that precedes in orderly steps through tissue levels. First, enlarge the wound for adequate exposure. Only non-viable wound margins need be excised. Define the depths of the wound and examine it thoroughly. Protect blood vessels and nerves, tendon sheaths, healthy periosteum, and soft tissue attached to bone.

Next, systematically excise all dead or significantly injured tissue from each tissue layer:

- Subcutaneous tissues

- Fascia

- Muscle

- Bone

At each level, leave only clearly viable tissue.

Bone fragments without blood supply should be removed. Contaminated or non-viable bone surfaces will also need excision.

Abundant irrigation helps to remove bacteria, pieces of dead tissue and blood clot, and improves the surgeon’s ability to examine the wound.

Fractures with open joint injuries

When an open fracture communicates with a joint, special surgical tactics are required. As always, all devitalized tissue must be removed. Joint surfaces should not be allowed to become dry. If possible, the soft-tissue envelope over the joint should be closed to minimize subsequent contamination. If this is not possible, the joint must be kept clean and moist (using a moisture-retaining dressing). Early definitive closure should be planned.

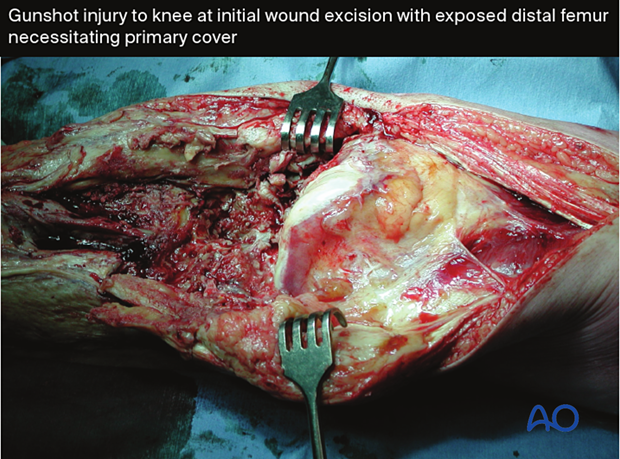

Fixation of open fractures

Open fractures need surgical fixation. Bone stability helps the open fracture wound recover by providing the best possible setting for soft-tissue healing and resistance to infection. Surgical fixation, with either external or internal means, is the best way to stabilize an open fracture. This is done after adequate debridement.

For lower-grade open fractures, use fixation that would be appropriate for similar closed injuries. For severe open fractures, or wounds that need repeated debridement, external fixation can be used. Definitive internal fixation can then be performed once all nonviable tissue has been debrided, and the soft-tissue envelope can be covered.

Intramedullary (IM) nailing may be the optimal fixation for femoral or tibial diaphyseal fractures. If this must be delayed (due to significant wound contamination, etc.), temporary external fixation can be used for initial stabilization.

Wound closure for open fractures

Wound closure should take place after debridement is complete. Delayed closure is safer for contaminated wounds. It is important to watch for infection and treat it promptly if it occurs.

After debridement has been satisfactorily completed, in one or more procedures, consideration must be given to choosing the best means of wound closure. Immediate wound closure can be considered for low-energy fractures and benign wounds.

Excessive skin tension interferes with wound healing. Furthermore, a contaminated wound is more likely to become infected after primary closure. Temporary open wound management with delayed primary closure is thus often the safest approach for significant open fractures.

If primary closure is chosen, the surgeon must watch carefully for signs of wound infection.

If closure is delayed, it should be completed as soon as possible to minimize the risk of nosocomial infection.

Open wound care

When caring for open wounds:

- Avoid contamination

- Avoid desiccation

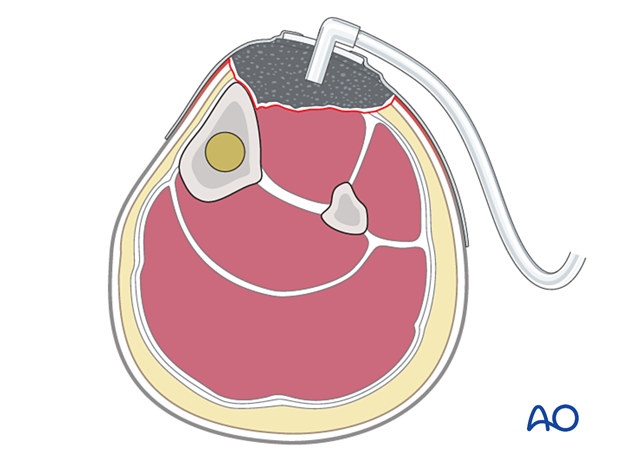

- Consider the use of a special dressing, eg, antibiotic bead pouch or vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device

- Close promptly

An open wound needs to be protected from contamination. A sealed dressing (eg, antibiotic bead pouch or VAC) can be used. A VAC can help to reduce the size of an open wound and promote the formation of granulation tissue. This device may permit early split-thickness skin grafting.

Closure with local or free flaps is typically appropriate for larger and more complicated wounds, as soon as staged debridement is complete.

It is important to close a complex wound promptly rather than leaving it open and risking superinfection.

Primary amputation for open fractures

Some extremity injuries are so severe that amputation is a better option than limb salvage. In fact, efforts at salvage may be doomed to failure, with risk of life-threatening complications, particularly infection.

Deciding whether to amputate or try to save a severely injured limb is one of the most controversial choices in the field of trauma care. It is essential to begin with awareness that a mangled extremity is a life-threatening injury. The patient’s ability to tolerate injury and extensive treatment must be considered. Limb salvage usually requires multiple operations, prolonged hospitalizations, and frequently results in serious complications. Awareness of the risks of limb salvage helps moderate the surgeon’s desire to save a limb at any cost. Appropriate primary amputation usually results in a wound which heals satisfactorily, effectively preventing infection.

Whenever possible, options and outcomes must be discussed with the patient and/or family at an early stage, before amputation, or before setting out on a complex, prolonged, and complicated path of reconstruction.

Since prostheses are generally more functional replacements for lower than upper extremities, additional risks may be worth considering to save a severely-injured upper extremity.

4. Modifiable risk factors

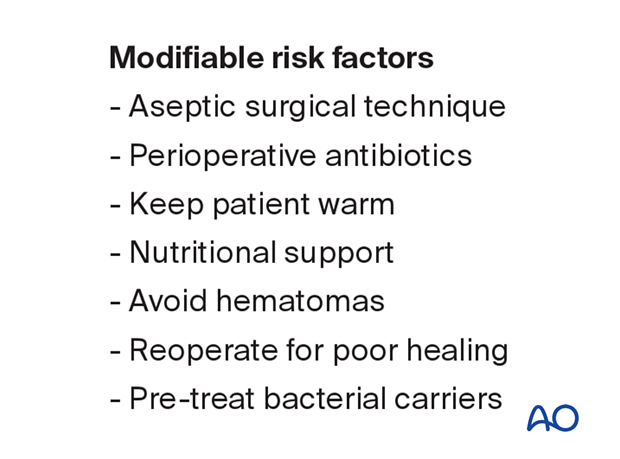

Aseptic surgical technique

A key principle of safe surgical treatment is to minimize the number of bacteria that might enter the surgical wound. Appropriate preoperative skin decontamination with washing and antibacterial agents is a mainstay for this. Similarly, use of sterile drapes, instruments and implants, and the maintenance of sterility throughout the procedure are also important. In the absence of optimal sterility, only the most limited emergency surgery should be carried out (eg, emergency debridement of an open fracture).

Perioperative antibiotics

Intravenous antibiotics, given within the hour before surgery, significantly reduce the incidence of operative wound infection. Typically, infections are due to skin flora entering the wound. Thus, the appropriate antibiotic is one that targets typical skin flora. In many countries, a first-generation cephalosporin is selected (eg, Cefazolin 1–2 grams, repeated during longer cases). Alternative agents may be selected to cover other bacteria, or in case of allergy.

Perioperative antibiotics should be given briefly, to avoid selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. A period of 24 hours, or less, is sufficient.

Keep patient warm

Should a patient’s core temperature fall below normal during surgery, the risk of infection becomes greater. For this reason, every effort must be made to minimize intraoperative heat loss, using appropriate covers and external warming devices.

Nutritional support

Nutritional supplements, vitamin supplements, and other forms of nutritional support should be considered prior to elective surgery and instituted as soon as possible after emergency surgery.

Malnourished patients have difficulty healing wounds and resisting infection. Simple screening tests, such as total lymphocyte count, or serum albumin level, with a careful dietary history and physical exam help to identify patients with inadequate nourishment. If possible, severe malnutrition should be corrected before elective fracture surgery.

Avoid hematomas

Continued bleeding with accumulated hematoma increases the risk of infection. This is particularly true of continued wound drainage, which may be bloody or serous. Thus, the surgeon should obtain hemostasis with care, consider suction drainage of selected wounds, and observe the patient carefully for persistent drainage. Should drainage continue, wound exploration and hematoma evacuation should be considered to stop the drainage and promote wound healing. This must be done in the operating room under sterile conditions. Cultures must always be obtained from the wound depths since bacterial colonization may have occurred and should be treated with specific antibiotics.

Reoperate for poor healing

If benign progressive wound healing does not occur, risk of infection steadily increases. Debridement of ischemic or necrotic skin edges and subcutaneous tissue should be done promptly, and healthy wound coverage achieved with suture closure, or flaps, as needed. Prompt closure of such a wound is the best means of avoiding infection.

Pre-treat bacterial carriers

Some patients have skin colonization of particularly virulent and antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). These are typically carried in the nares. Screening cultures permit identification of such carriers prior to elective surgery and treatment with antibacterial ointment, and skin cleansers can significantly reduce the risk of infection.

Alternatively, for patients at significant risk of MRSA colonization, consider use of vancomycin for perioperative prophylaxis.