Reverse arthroplasty

1. Principles

General remarks

Fixation of proximal humeral fractures is frequently associated with problems related to the healing of the tuberosities and/or the humeral head fragment. If the tuberosities heal in a grossly displaced position the clinical outcome is poor and may require further surgery. For this reason, reverse shoulder arthroplasty is an attractive option in elderly patients. Since this kind of shoulder replacement does not rely on the function of the rotator cuff, it provides predictable results in terms of pain relief and shoulder function in one operation.

Indications

The indications for reverse shoulder arthroplasty in proximal humeral fractures are still not clear. Recent published clinical results suggest a growing spectrum of indications. The classic indication was a displaced four-part fracture in an elderly patient, especially if the tuberosities are comminuted or very small avulsion fractures. More recently, under such conditions, even three- and two-part fractures may be considered.

Keys to successful reverse shoulder arthroplasties

- Correct determination of the surgical landmarks

- Extensive soft tissue release

- Proper determination of prosthesis size and version

- Proper height of the prosthesis with correct soft-tissue tensions

- Stable fixation of the tuberosities to promote their union to the proximal humerus

2. Patient preparation and approaches

Patient preparation

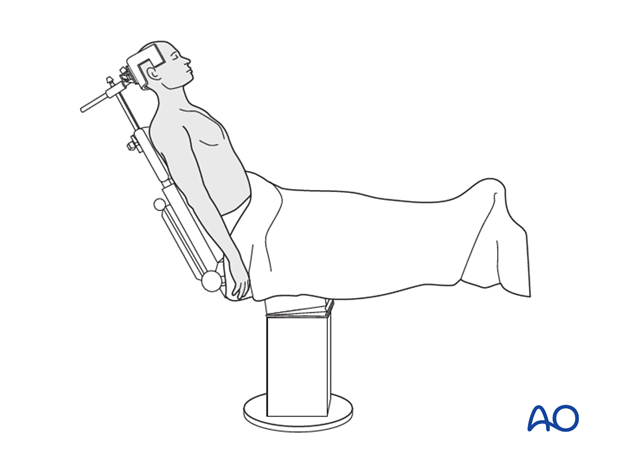

It is recommended to perform this procedure with the patient in a beach chair position.

Alternatively the patient may be positioned supine if the procedure is converted from ORIF.

Recommended approach

The deltopectoral approach is recommended.

The anterolateral and transdeltoid lateral approach can be used but are not recommended because of:

- Risk of axillary nerve injury

- Risk of deltoid muscle injury

3. Evaluation of the fracture

It is crucial to evaluate the fracture. Identify the fracture lines, the long head of the biceps and the condition of the rotator cuff.

4. Tenotomy of the long head of the biceps

The biceps tendon may be attached to the superior border of the pectoralis major with a simple suture. Perform a tenotomy of the long head of the biceps close to the rotator interval.

Pearl: Move the stump of the biceps tendon out of the surgical field.

5. Surgical technique for two- or three-part fracture

Principles

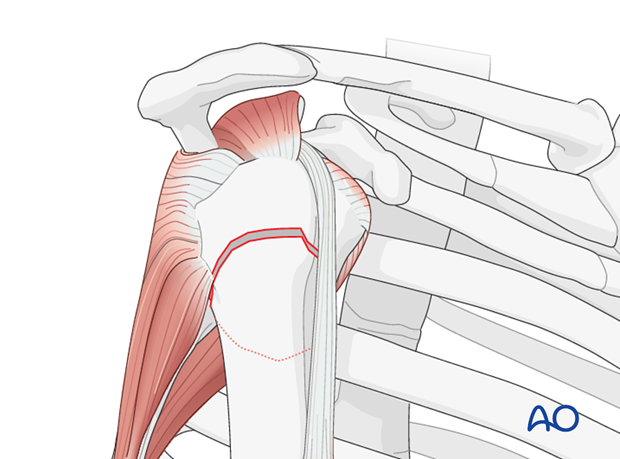

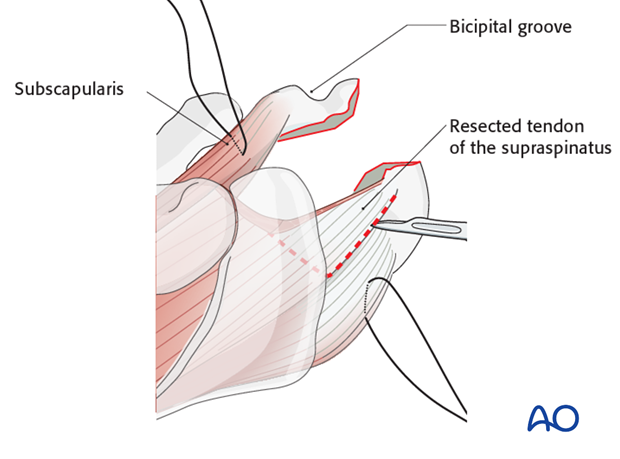

The greater and lesser tuberosities must be isolated and free of cartilage. The subscapularis tendon and the infraspinatus tendon should be mobilized and secured with a stay suture. The supraspinatus tendon should be excised.

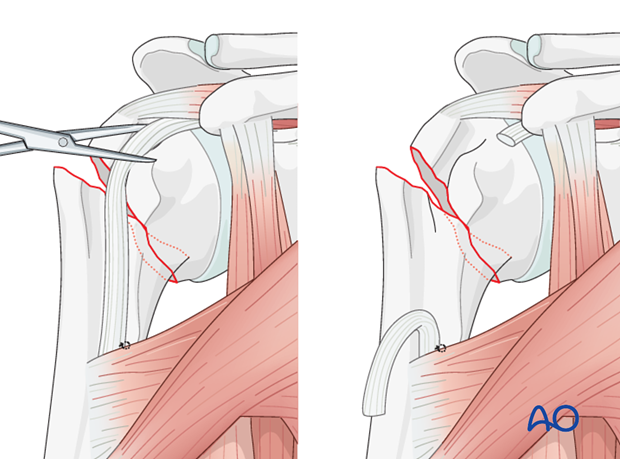

Osteotomy of the lesser tuberosity

If the lesser tuberosity is still attached it must be detached.

Incise the rotator interval with scissors.

Perform an osteotomy of the lesser tuberosity; start at the deepest point of the bicipital groove. Crack the lesser tuberosity off with a gentle twist of the osteotome. Incise the remaining anterior capsule and release the lesser tuberosity. Remove any remaining cartilage if present.

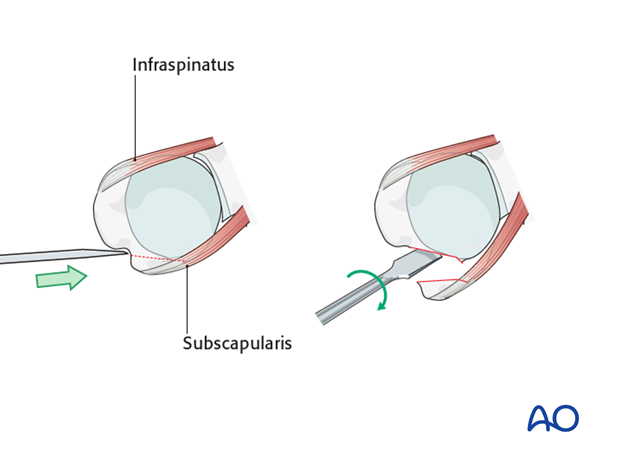

Osteotomy of the greater tuberosity

If the greater tuberosity is still attached it must be detached.

Perform an osteotomy of the greater tuberosity. Again, start at the deepest point of the bicipital groove and tilt the osteotome posteriorly parallel to the greater tuberosity. Crack the greater tuberosity off with a gentle twist of the osteotome. Incise the remaining posterior capsule and release the greater tuberosity. Remove any remaining cartilage if present.

6. Preparation of the joint for placement of prosthesis

Retrieve the humeral head

Any remaining medial capsular attachment to the head should be carefully released, paying special attention not to damage the axillary nerve medial to the proximal humerus.

Be sure that all loose small fragments are removed.

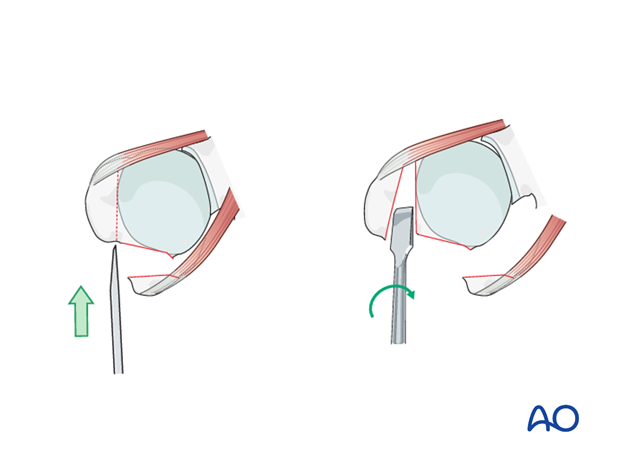

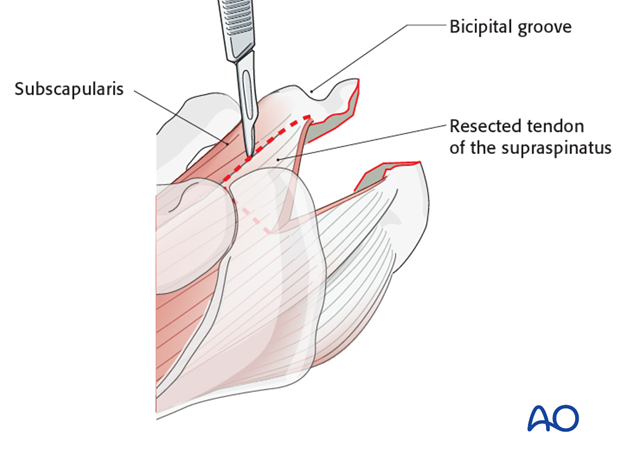

Mobilization and preparation of the lesser tuberosity

Resect the anterior part of the supraspinatus tendon and the rotator interval up to the superior border of the subscapularis tendon. Remove all scar tissue around the subscapularis tendon. Remove adjacent cartilage if remaining. Secure the subscapularis tendon with a stay suture.

Mobilization and preparation of the greater tuberosity

Resect the posterior part of the supraspinatus tendon up to the superior border of the infraspinatus tendon. Mobilize the infraspinatus tendon and secure it with a stay suture. Remove adjacent cartilage of the greater tuberosity if remaining.

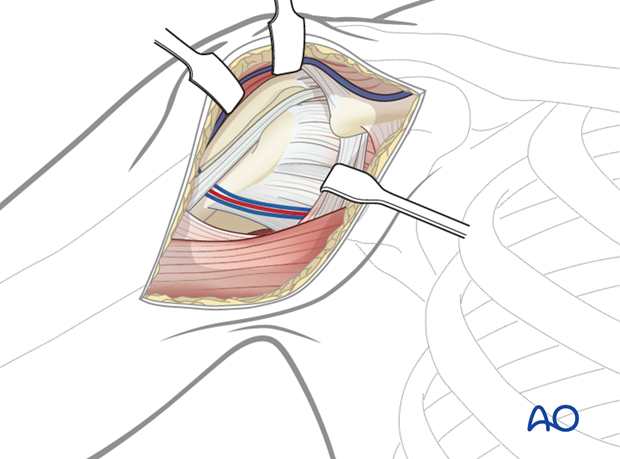

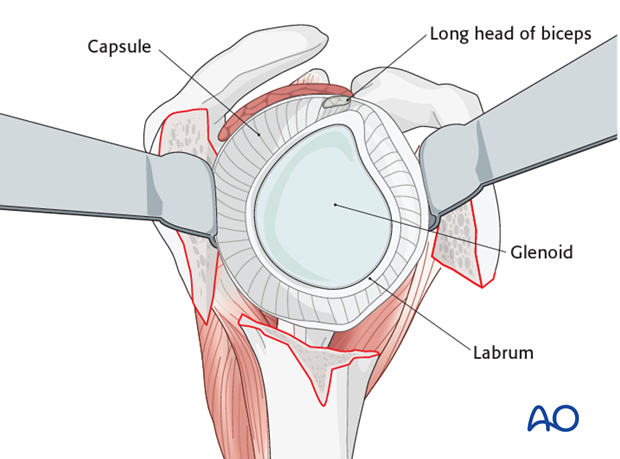

Exposure of the glenoid

Expose the glenoid between retractors which are placed at the anterior and posterior rim of the glenoid.

Glenoid-sided soft-tissue release

Perform a complete soft-tissue release around the glenoid. Start with the resection of the anterosuperior labrum including the remnants of the biceps. Continue with an anterior, inferior and later posterior release. Place retractors at the anterior, inferior and posterior rim of the glenoid.

Inspect the glenoid fossa in order to rule out any additional injury.

If there is a glenoid fracture, osteosynthesis should be performed now.

Remove any bony fragments.

7. Glenoid surgical steps

General remarks

For reverse shoulder arthroplasty, various prosthetic systems are available.

The principles of the procedure are shown here on a representative example of one system. For detailed information, refer to the manufacturer’s manual.

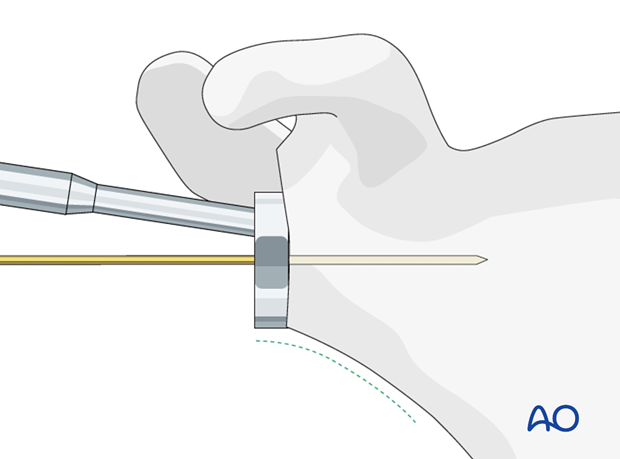

Glenoidal preparation

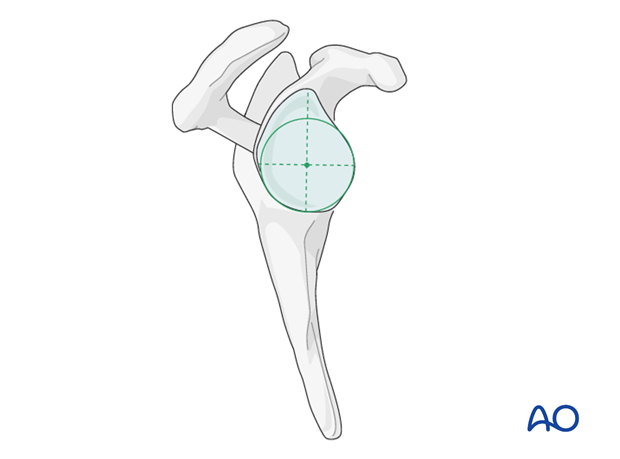

Place the guide plate on to the glenoid surface so that it is flush with the circle of the lower glenoid (green line). Fix the guide plate with a central K-wire.

The K-wire (and therefore later the central peg) should be positioned in the center of the inferior circle of the glenoid.

Control the position of the K-wire with preoperative planning including radiographic and CT images.

Use a cannulated glenoid resurfacing reamer to remove the cartilage and to create a smooth surface of the glenoid to provide full contact with the base plate.

Extend the glenoidal preparation superiorly with an additional cannulated surface reamer to assure later pressfit fixation of the glenosphere to the base plate without any bony or soft-tissue impingement.

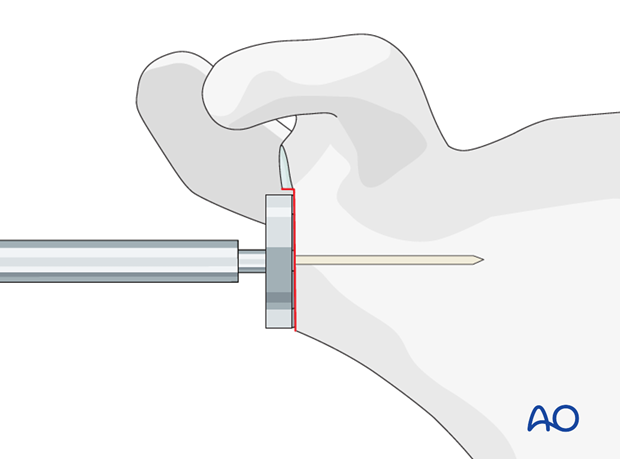

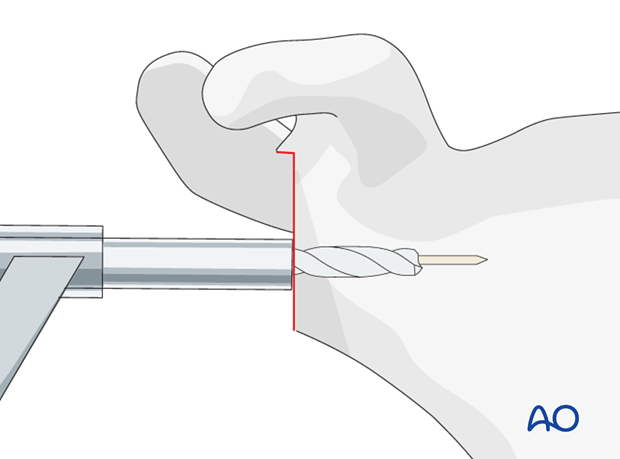

Drill the hole for the central peg using a cannulated drill.

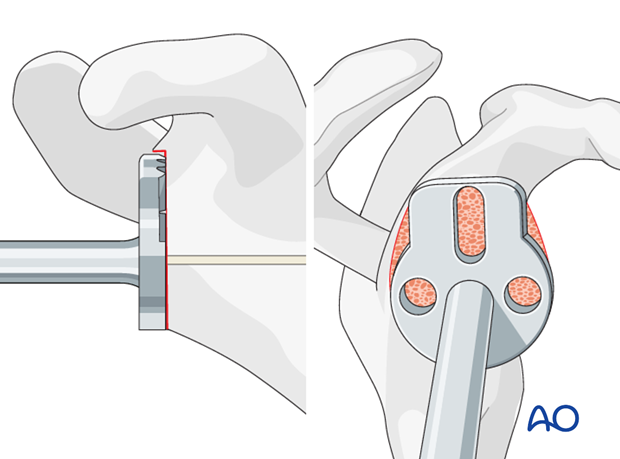

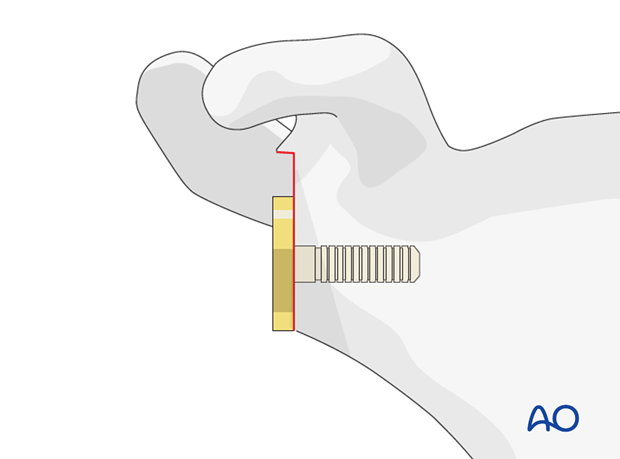

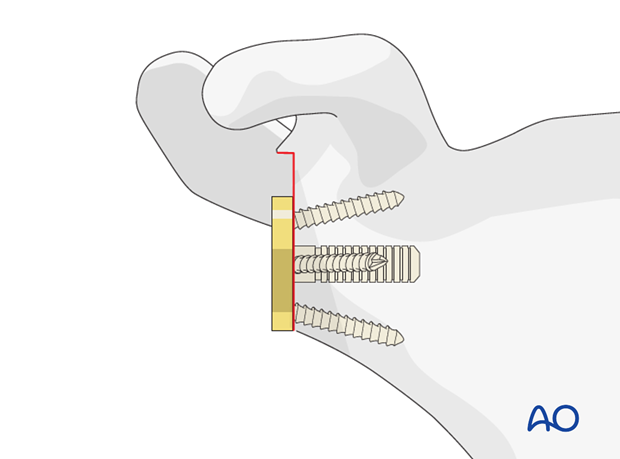

Align the base plate and implant it with gentle taps of a mallet.

Fix the base plate with screws according to the manufacturer’s manual.

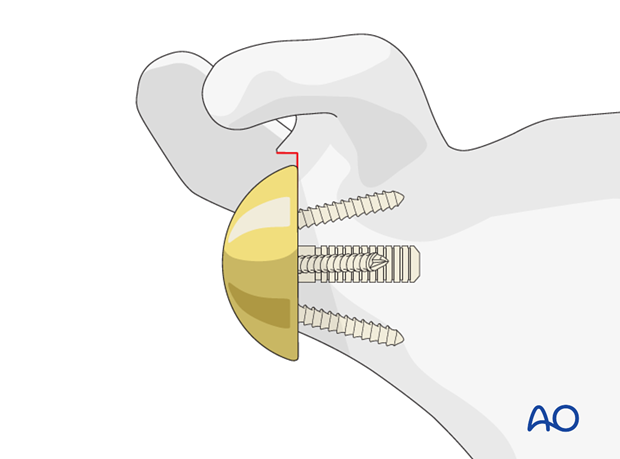

Glenosphere implantation

Implant the glenosphere. A trial glenosphere may be used instead of the definitive one.

Note: The size of the glenosphere should be bigger than the AP diameter of the glenoid in order to prevent impingement. The glenosphere should also have a slight inferior overhang in order to minimize the risk of inferior notching.

8. Humerus surgical steps

Exposure of the proximal humerus

Expose the proximal humerus with retroflexion and adduction of the humerus so that the fracture plane lies in front of the glenosphere. Additional upwards pushing is helpful. Anterior and posterior retractors placed behind the proximal humerus may improve the exposure.

Preparation of the intramedullary canal

Prepare the intramedullary canal with reamers of increasing diameters until the cortical bone of the humerus is reached. Take care to be gentle in osteoporotic bone in order to prevent iatrogenic fractures.

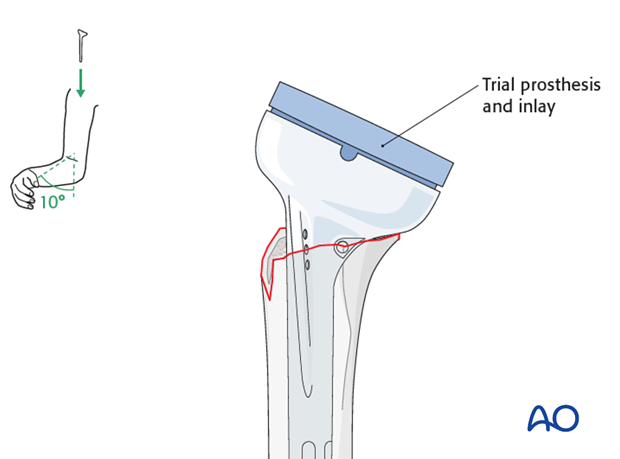

Placement of a humeral trial prosthesis

Insert the humeral trial prosthesis determined by the size of the last reamer.

Mount a standard trial inlay according to the size of the glenosphere. There is some debate about the ideal retrotorsion of the prosthesis. We recommend a retrotorsion of 10°.

Reduction and assessment of joint tensioning and stability

Reduce the prosthesis and confirm proper joint tension and stability. Do not overtension the deltoid muscle. Check if there is any unwanted impingement.

If necessary repeat this step with different inlays.

Mark the position of the trial implant in relation to the humerus.

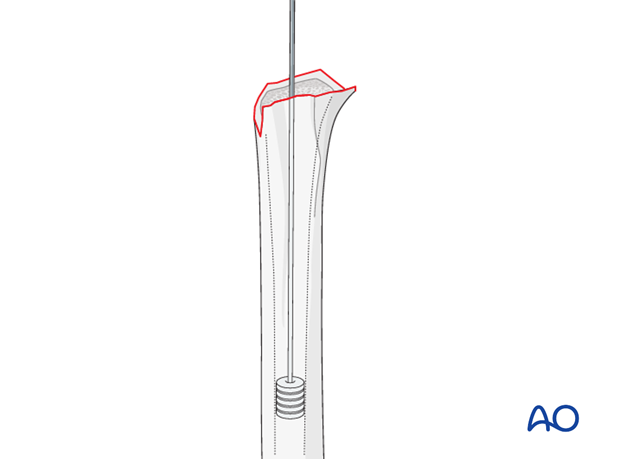

Preparation of the humerus for cementing

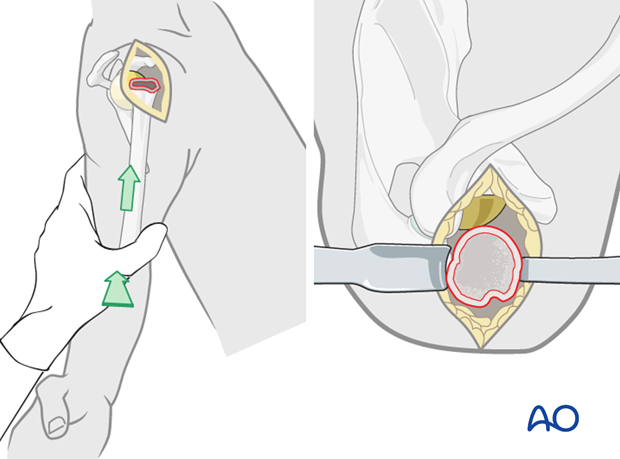

Expose the proximal humerus again and prepare the intramedullary cavity with pulsed lavage and a medullary canal stopper.

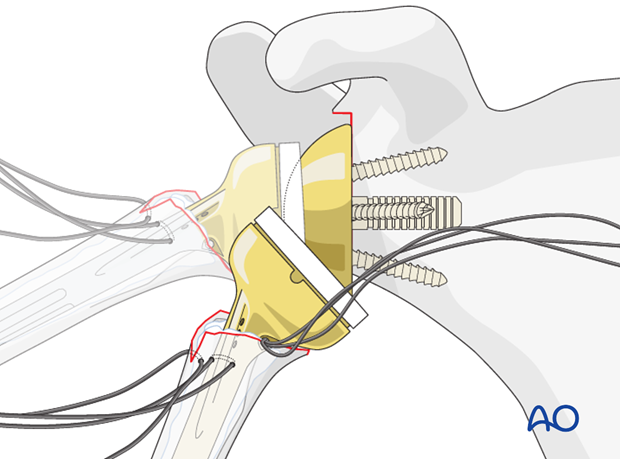

Drill two 2.0 mm holes through the humeral shaft on each side of the bicipital groove and pass a heavy, non-resorbable suture through each side.

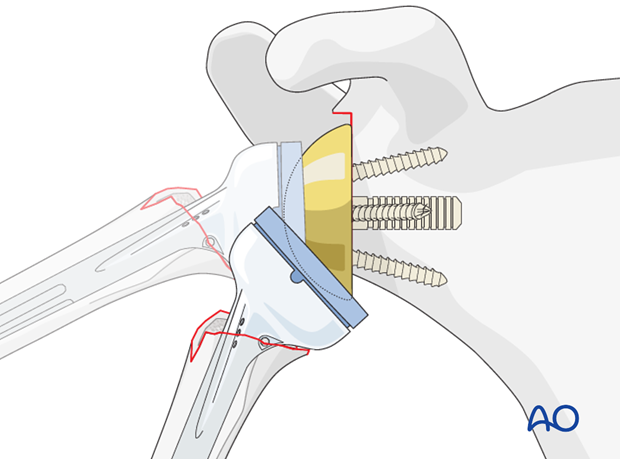

Pass three heavy, non-resorbable sutures through the infraspinatus tendon, the medial suture hole of the definitive prosthesis and the subscapularis tendon. These sutures will help to fix the tuberosities to the prosthesis later.

Implantation of the definitive prosthesis

Typically, a cemented fixation of the definitive prosthesis is necessary.

Cement the prosthesis in the previously chosen position in respect to the prosthesis height and retrotorsion.

After hardening of the cement, insert the chosen inlay and reduce the prosthesis.

Confirm correct soft-tissue tension and stability.

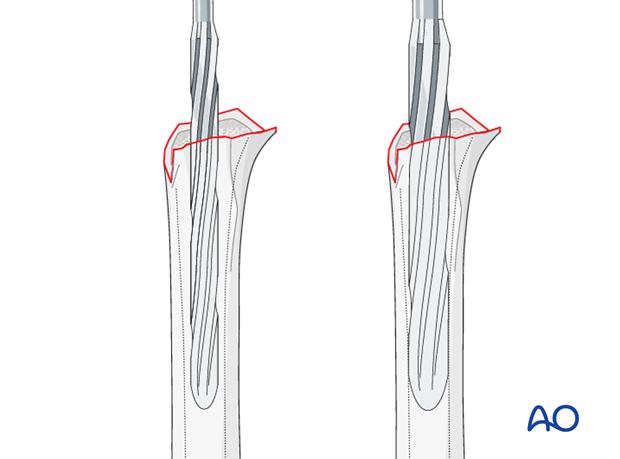

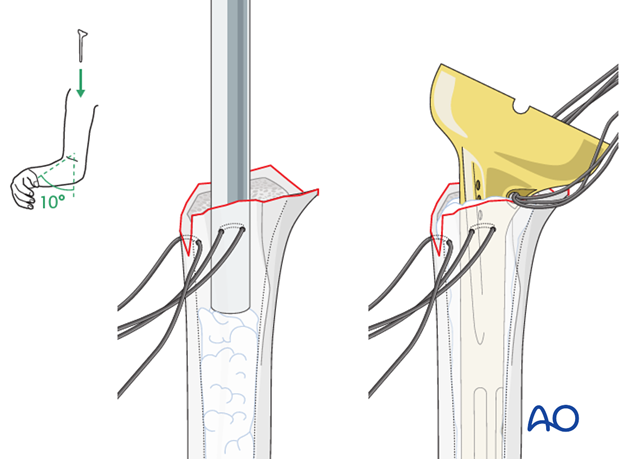

9. Fixation of the tuberosities

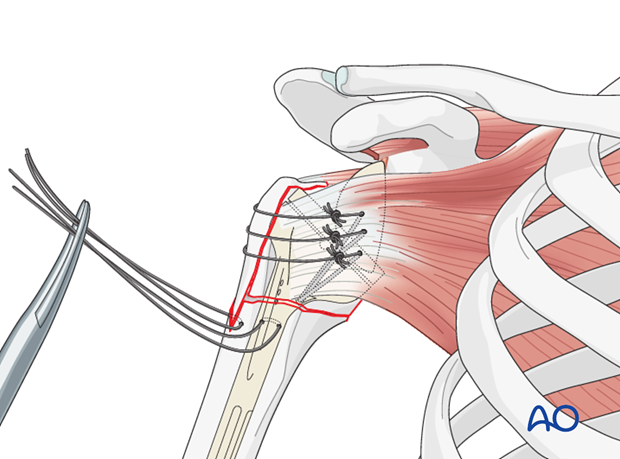

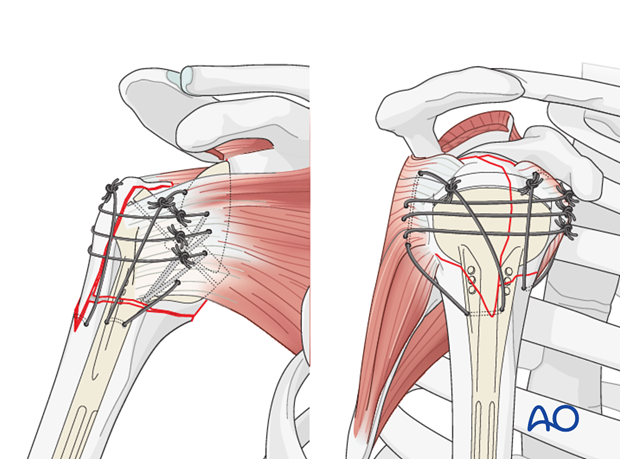

Reduce the tuberosities so that they have contact with the humeral shaft. A slight overlap ensures better bony healing of the tuberosities.

Start with tying the three horizontal sutures embracing the tuberosities around the prosthesis.

Pass the prepared sutures from the humeral shaft through the infraspinatus and the subscapularis tendon and tie the sutures, in order to prevent a superior dislocation of the tuberosities.

Confirm the final position of the tuberosities and the position of the implants with an image intensifier. Take care to obtain a true AP projection to judge the glenoid.

10. Rehabilitation

Overview of rehabilitation

The shoulder is perhaps the most challenging joint to rehabilitate both postoperatively and after conservative treatment. Early passive motion according to pain tolerance can usually be started after the first postoperative day - even following major reconstruction or prosthetic replacement. The program of rehabilitation has to be adjusted to the ability and expectations of the patient and the quality and stability of the repair. Poor purchase of screws in osteoporotic bone, concern about soft-tissue healing (eg tendons or ligaments) or other special conditions (eg percutaneous cannulated screw fixation without tension-absorbing sutures) may enforce delay in beginning passive motion, often performed by a physiotherapist.

The full exercise program progresses to protected active and then self-assisted exercises. The stretching and strengthening phases follow. The ultimate goal is to regain strength and full function.

Postoperative physiotherapy must be carefully supervised. Some surgeons choose to manage their patient’s rehabilitation without a separate therapist, but still recognize the importance of carefully instructing and monitoring their patient’s recovery.

Activities of daily living (ADL) can generally be resumed while avoiding certain stresses on the shoulder. Mild pain and some restriction of movement should not interfere with this. The more severe the initial displacement of a fracture, and the older the patient, the greater will be the likelihood of some residual loss of motion.

Progress of physiotherapy and callus formation should be monitored regularly. If weakness is greater than expected or fails to improve, the possibility of a nerve injury or a rotator cuff tear must be considered.

With regard to loss of motion, closed manipulation of the joint under anesthesia, may be indicated, once healing is sufficiently advanced. However, the danger of fixation loosening, or of a new fracture, especially in elderly patients, should be kept in mind. Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions or even open release and manipulation may be considered under certain circumstances, especially in younger individuals.

Special considerations for humeral head replacement

Following osteosynthesis of the tuberosities in combination with a hemiarthroplasty or a reverse shoulder arthroplasty rehabilitation must take into account the suture fixation of the tuberosities. It is recommended to place the arm in a neutral position on an abduction pillow for 6 weeks to ensure uneventful healing of the tuberosities. During this time, active assisted motion and therapy on a continuous passive motion (CPM) chair is helpful to prevent shoulder stiffness.

After removal of the abduction pillow, active motion over the horizontal plane is allowed and trained.

Shoulder rehabilitation protocol

Generally, shoulder rehabilitation protocols can be divided into three phases. Gentle range of motion can often begin early without stressing fixation or soft-tissue repair. Gentle assisted motion can frequently begin within a few weeks, the exact time and restriction depends on the injury and the patient. Resistance exercises to build strength and endurance should be delayed until bone and soft-tissue healing is secure. The schedule may need to be adjusted for each patient.

An example of a dedicated rehabilitation program for fractures in combination with reverse shoulder arthroplasty is shown below. This protocol addresses the fixed tuberosities which have to be protected for uneventful healing. This protocol can be modified according to the individual needs and expectations.

Phase 1 (approximately first 6 weeks)

Bandage

- Immobilization on a shoulder abduction pillow in neutral position of rotation

Range of motion

- Passive motion within the pain free interval for abduction, adduction and flexion

- No internal or external rotation

- No retroflexion

- Glenohumeral motion up to 90°

- ADL for eating and writing allowed

Physiotherapy

- Passive motion up to 90°

- Preservation and training of scapula mobility (manual therapy and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching)

- Relaxation/stretching of neck muscles

- Training of elbow and hand functions

- Specific stabilization therapy for the glenohumeral joint

- Isometric exercises in all directions

- Treatment of scars after proper wound healing

- CPM up to 90° of abduction

Massage

- Neck

- Shoulder girdle

- Thoracic spine

Lymph drainage

- During hospitalization

Ice/warmth

- Ice/cold air for pain reduction

Training therapy

- Training of the contralateral arm (overflow cardiovascular training)

Phase 2 (approximately week 7-11)

Bandage

- No longer required

Range of motion

- Assisted/active motion within the pain free interval, also beyond 90°

- Careful rotation

Physiotherapy

- Free motion of shoulder girdle (scapula, clavicle, cervicothoracic junction, cervical and thoracic spine) with specific mobilization and decontraction techniques (manual therapy)

- Strengthening exercises especially for ADL

- Eccentric muscle activity

Massage

- As required

Lymph drainage

- As required

Ice/warmth

- As required

Training therapy

- Mobilization bath, wound permitting

- Training of hand and forearm muscles

- Set for shoulder therapy

- 3D movement pattern with pulling device

Phase 3 (after week 11)

Range of motion

- No restrictions on glenohumeral movement

- Muscle growth for shoulder girdle and all arm muscles

Physiotherapy

- All physiotherapeutic techniques allowed, active and against resistance

- Increasing eccentric muscle activity

Training therapy

- Handcycling

- Training for specific ADL and sports

- Machine training

- Free weight training