Deltopectoral approach to the proximal humerus

1. Indication

The (anterior) deltopectoral approach can be used for almost any proximal humeral fracture treatment and is often the preferred approach.

This approach is also highly recommended for revision surgery.

2. Anatomy

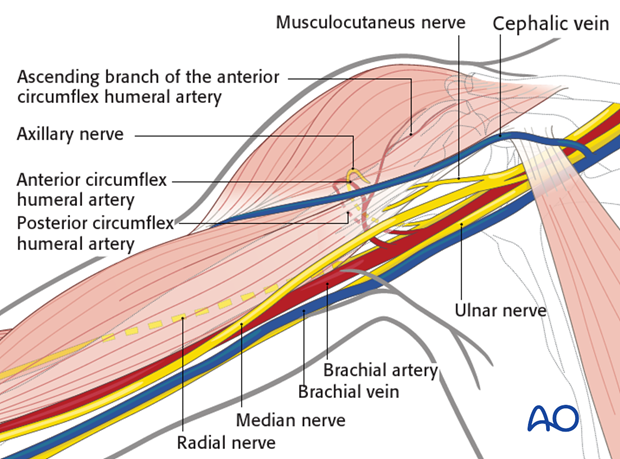

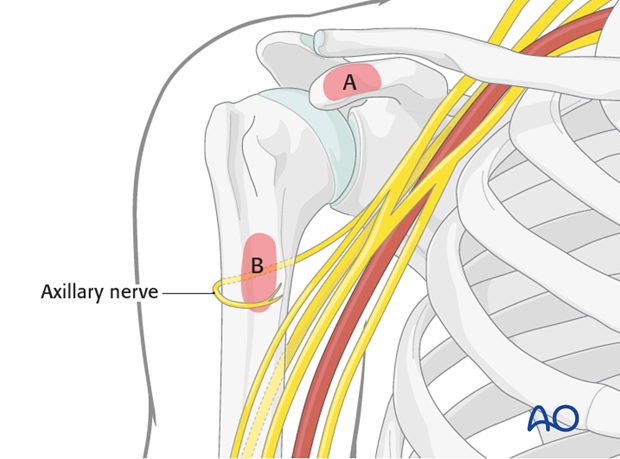

The course of the following neurovascular structures should be kept in mind:

- Cephalic vein

- Anterior circumflex humeral artery

- Ascending branch of the anterior circumflex humeral artery

- Posterior circumflex humeral artery

- Musculocutaneus nerve

- Axillary nerve

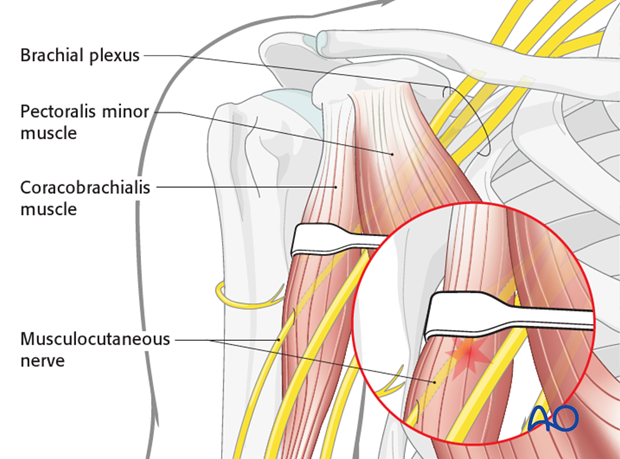

Further neurovascular structures, eg the brachial plexus, are only at risk if there is a rigorous retraction.

Anatomical landmarks for the anterior deltopectoral approach are:

- Coracoid process (A)

- Proximal humeral shaft (on the level of the axilla; B)

Both landmarks can easily be palpated.

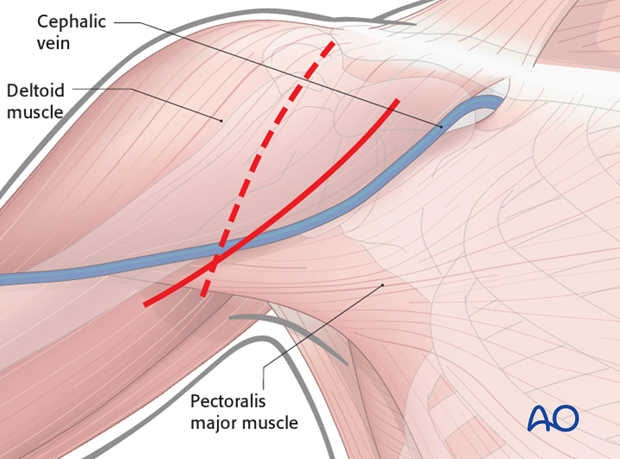

3. Skin incision

Make a 12–14 cm long skin incision between the coracoid process and the proximal humeral shaft. The shape of the skin incision can be straight or curved depending on surgeon’s preference.

For an arthroplasty for degenerative diseases, a rather vertical incision may be preferred (dashed line).

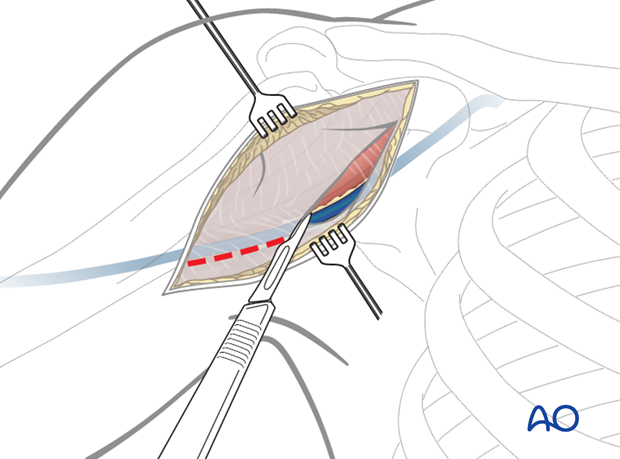

4. Exposure of the superficial fascia

Expose the deltopectoral groove with the cephalic vein. These structures can be identified by:

- The course of the muscle fibers

- The cephalic vein itself

- Fat tissue surrounding the vein

If in doubt, look for the deltopectoral groove at the proximal and/or distal end of the skin incision. (The sulcus is slightly more pronounced and in cases of revision surgery less scarred.)

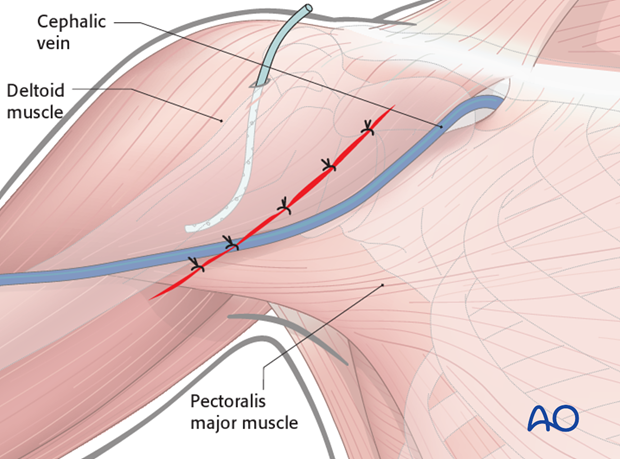

5. Dissection down to the deltopectoral groove

Retract the cephalic vein laterally or medially, and open along the groove. If retracted laterally, the anatomical drainage of blood from the deltoid muscle is respected but it is at risk of damage by retractors during surgery. In any case, the cephalic vein should be preserved to reduce the surgical edema of the limb.

Failure to find the deltopectoral groove can lead to difficulty in dissection of the deltoid and possibly to denervation of the anterior portion of the deltoid.

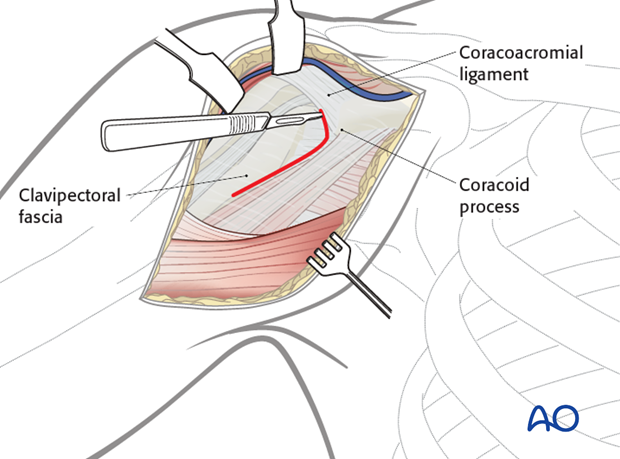

Bluntly dissect between and under the deltoid and pectoralis muscles down to expose the clavipectoral fascia.

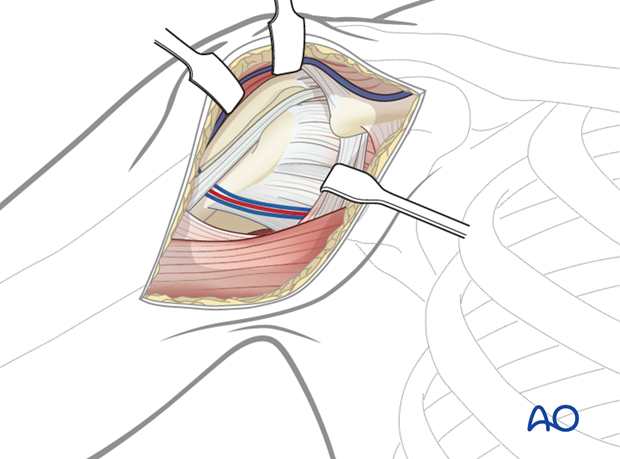

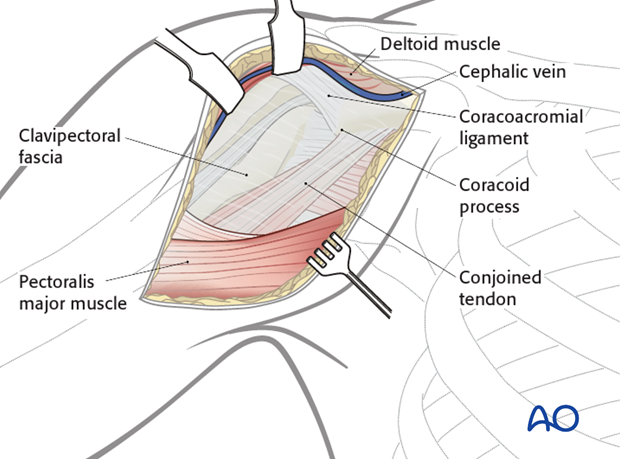

6. Exposure of the deep layers

Identify the coracoid process and the conjoined tendon.

Incise the clavipectoral fascia lateral to the conjoined tendon and inferior the coracoacromial ligament.

Retract the deltoid muscle laterally using a delta (modified Hohmann) retractor and the conjoined tendon medially using a Langenbeck retractor.

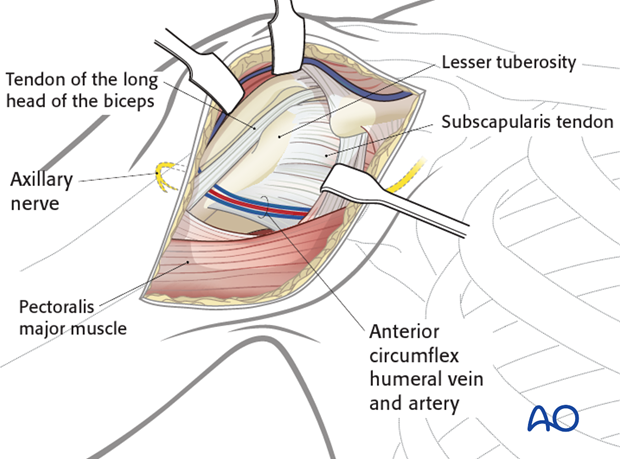

Expose the proximal humerus and confirm the anatomical landmarks (subscapularis tendon, lesser tuberosity, bicipital groove with the biceps tendon and the greater tuberosity). Evaluate the fracture morphology. Hemorrhagic bursa tissue has to be resected if needed.

Distally, expose the pectoralis major.

Pitfall: Be aware of retractor positioning (Roux or Hohmann retractor) to prevent iatrogenic damage of the axillary nerve.

Pitfall: The musculocutaneous nerve enters the coracobrachialis muscle as close as 2.5 cm distal to the tip of the coracoid. Retractors placed under the conjoined tendon can cause neurapraxia; therefore, vigorous retraction must be avoided.

Pearls:

- Using an additional delta retractor might be helpful to increase exposure of the proximal humerus.

- Exposure may be increased additionally by partially releasing the insertions of deltoid and/or pectoralis major.

- Shoulder abduction decreases tension on the deltoid, and makes it easier to retract laterally.

7. Intraarticular exposure

There are several ways to expose the intraarticular aspect of the glenohumeral joint:

- Incision of the rotator interval

- Opening through the fracture (dislocation of the lesser tuberosity fragment)

- Tenotomy of the subscapularis tendon

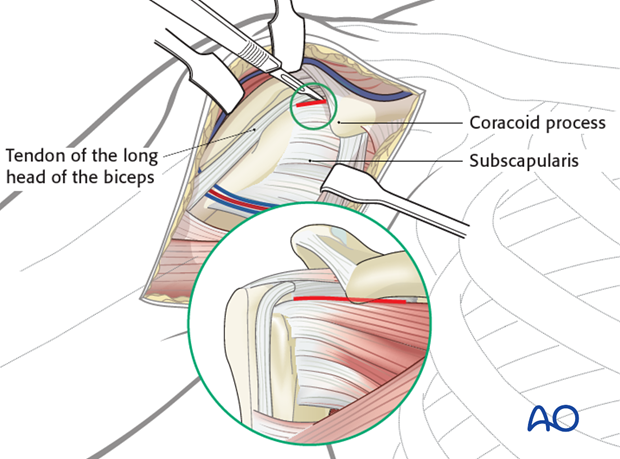

8. Incision of the rotator interval

Identify the course of the long head of the biceps and the upper border of the subscapularis tendon. Incise the rotator interval just at the upper border of the subscapularis tendon towards the coracoid process. It might be helpful to perform a tenotomy of the long head of the biceps close to the labrum and to remove the intraarticular portion of the biceps. This window creates a nice view to the anterosuperior parts of the humerus. It does not violate the function of the rotator cuff.

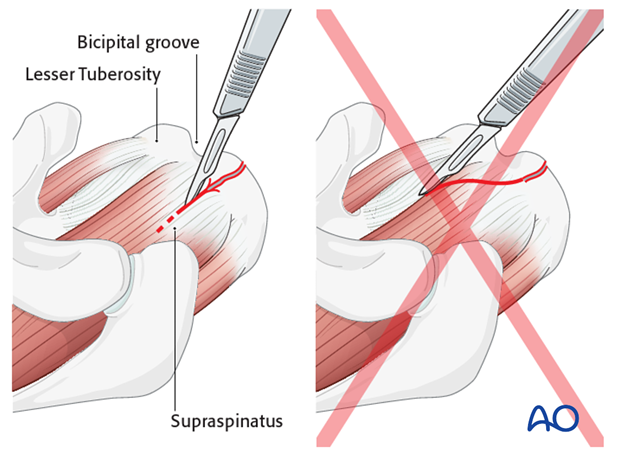

Pitfall: In fractures of the proximal humerus which consist of an anterior fragment one should take care to analyze the fracture pattern. If the anterior fragment consists of the lesser tuberosity, the bicipital groove and the anterior part of the greater tuberosity, it is strongly recommended to use a supraspinatus split in line of the fracture instead of the incision of the rotator interval.

9. Opening through the fracture

In fractures of the proximal humerus which consist of a lesser tuberosity fragment, it might be beneficial to open up the joint through the fracture between the greater and lesser tuberosity. Take care that the extension of the vertical fracture line between the tuberosities typically runs into the supraspinatus tendon and not into the rotator interval. Therefore, a split of the supraspinatus tendon is necessary to preserve the anterior insertion of the supraspinatus tendon.

10. Tenotomy of the subscapularis tendon

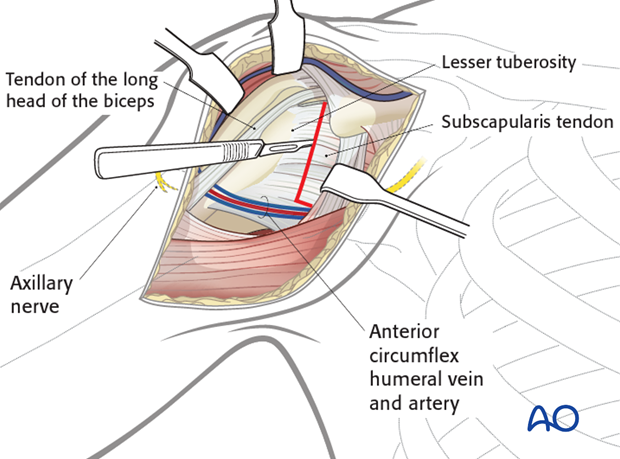

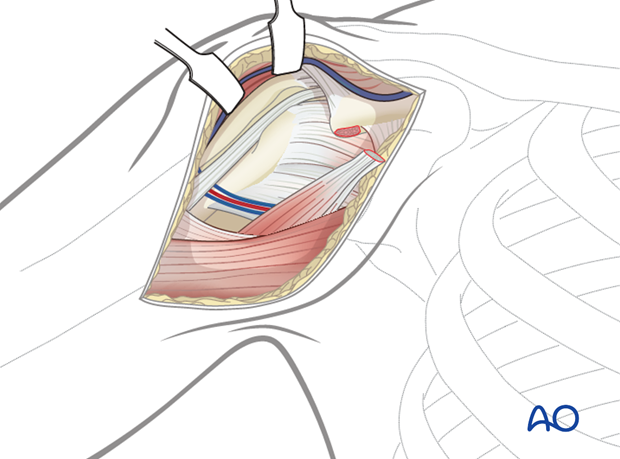

Satisfactory reduction of anatomical neck fractures may sometimes require an anterior shoulder arthrotomy.

The subscapularis tendon is identified and divided vertically lateral to the musculotendinous junction in line of the anatomical neck.

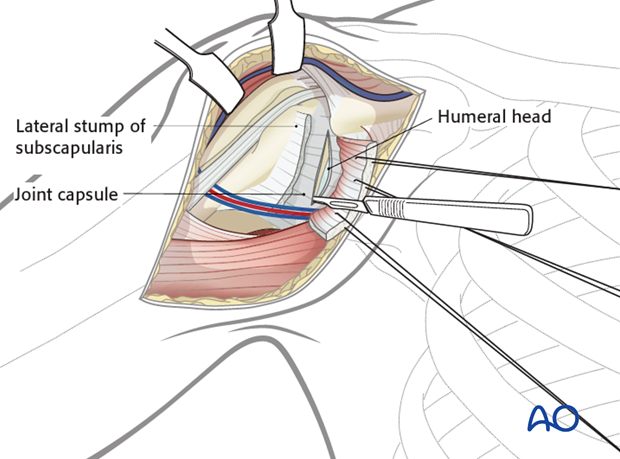

Reflect the subscapularis from the underlying joint capsule and enter the joint through a vertical capsulotomy, medial to the lateral stump of the subscapularis.

11. Tenotomy of the conjoined tendon/osteotomy of the tip of the coracoid process

If difficulty is encountered in trying to expose the axillary nerve, for example in a revision procedure following a previous attempt at fixation, it may be helpful to develop the course of the axillary nerve starting from unoperated tissues. This may be facilitated by reflecting the conjoined tendon from the tip of the coracoid, or with a small coracoid osteotomy.

12. Wound closure

Irrigate the wound. Placement of a drain underneath the deltoid muscle might be considered.

Close the deltopectoral groove, the subcutaneous tissues and the skin.