ORIF - Screw fixation

1. Principles

Indication

If the fracture plane is oblique and long enough, they may often be fixed satisfactorily with lag screws after reduction. Screws must have adequate purchase in the lateral cortex to provide stable fixation.

Disimpaction

Disimpaction is the key to successful reduction.

Proper reduction

After reduction, alignment should be correct in both sagittal and coronal planes. Rotational alignment must also be correct.

2. Patient preparation and approaches

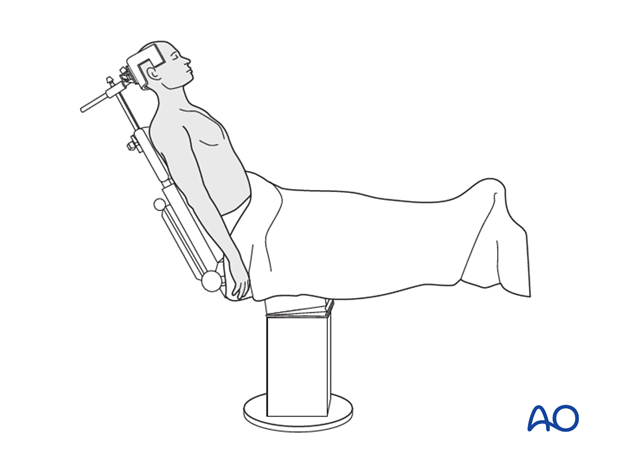

Patient preparation

It is recommended to perform this procedure with the patient in a beach chair position (with the supine position as alternative).

Approaches

Choose whichever approach is best suited for anticipated reduction maneuvers:

The deltopectoral approach, while more extensile, is more invasive.

3. Reduction and preliminary fixation

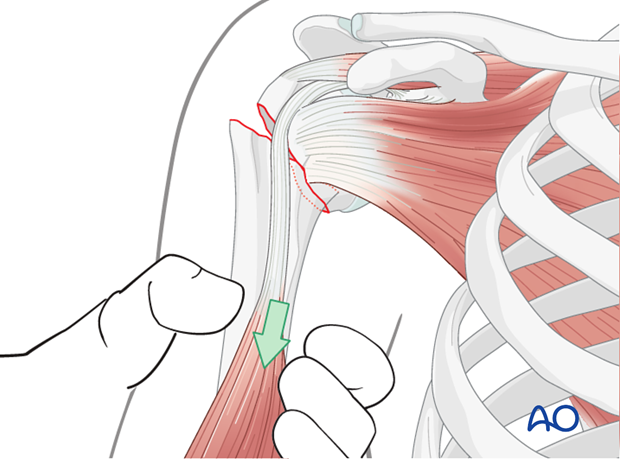

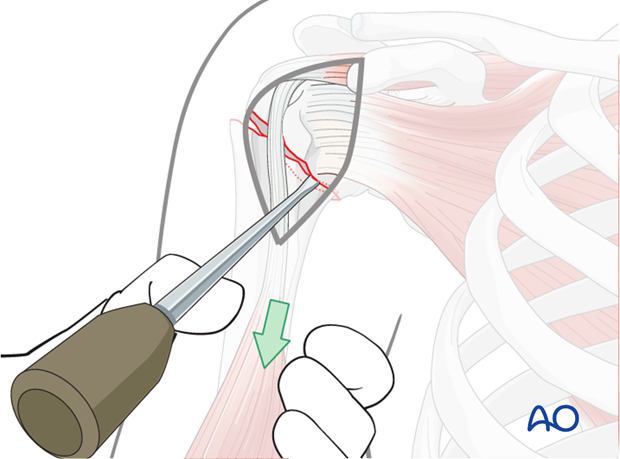

Reduction

Since these fractures involve an impaction, pure traction alone may not be effective to reduce the fracture.

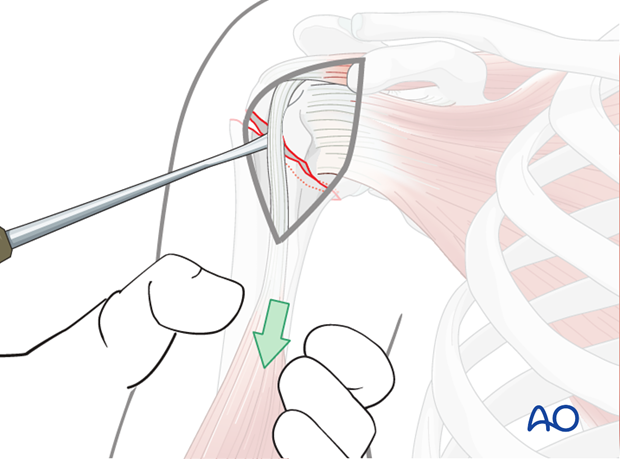

While longitudinal traction is applied to the limb, insert a periosteal elevator into the fracture gap to disimpact the fracture. The elevator should be inserted from the front and pointed medially and superiorly.

Due to the overlap, the periosteal elevator might not be inserted easily from anterior. If so, insert it into the gap between the fracture fragments. The periosteal elevator might then be used as a lever to disimpact the fragments.

Confirm proper rotational alignment

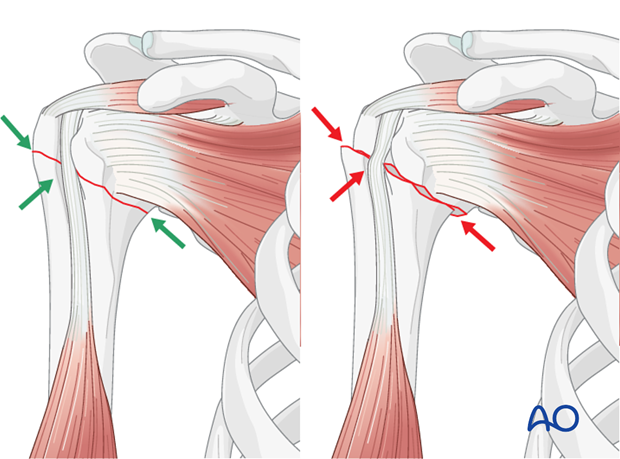

Correct rotational alignment must be confirmed. This can be done by matching the fracture configurations on both sides of the fracture. This would be useful in the more transverse fracture configuration as shown in the illustration.

Pearl: check retroversion

The bicipital groove might be a good indicator for correct rotation. In case of correct rotation, no gap/angulation is visible at the level of the fracture.

In these fractures the combined forces of the tendons are normally neutral, therefore, the humeral head is in neutral version. Remember that the humeral head is normally retroverted, facing approximately 25° posteriorly (mean range: 18°-30°) relative to the distal humeral epicondylar axis. This axis is perpendicular to the forearm with the elbow flexed to 90°.

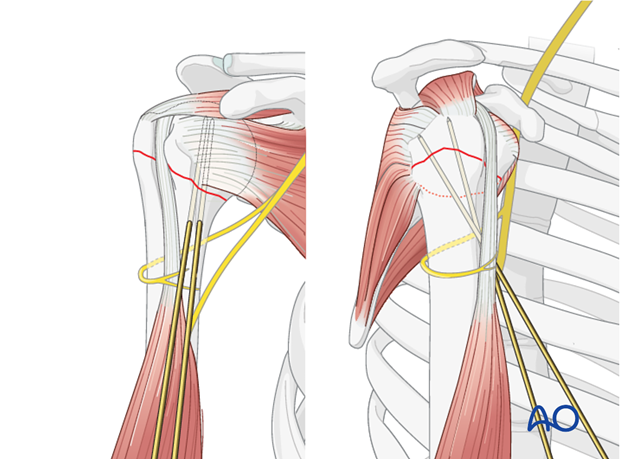

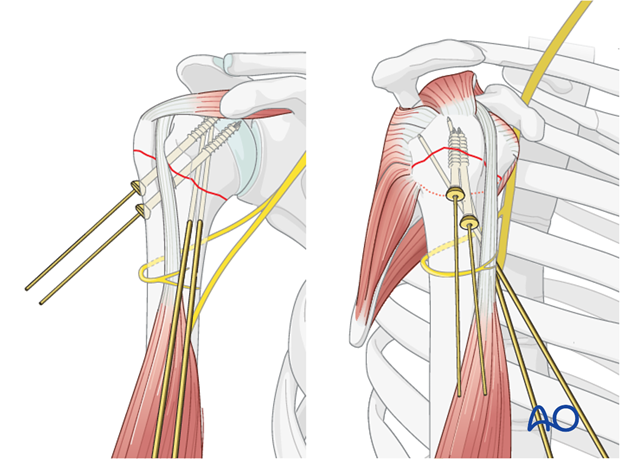

Preliminary fixation

Holding the reduction manually or with a pointed reduction forceps, temporarily secure it with 2 K-wires. Place them outside the foreseen screw position. The illustration shows two such K-wires placed from distal to proximal. Alternatively, they might be inserted from proximal to distal.

Avoid the path of the axillary nerve.

Confirm reduction

The correct reduction must be confirmed in both AP and lateral views by image intensification.

4. Fixation

Cannulated or non-cannulated screws can be used according to the surgeon’s preference. We illustrate the use of 3.5 mm cannulated screws. A larger diameter screw may be preferred for larger bone fragments, particularly in the surgical neck region. Since interfragmentary compression is desired, use a lag screw technique, with partially threaded screws inserted so screw threads do not cross the fracture line.

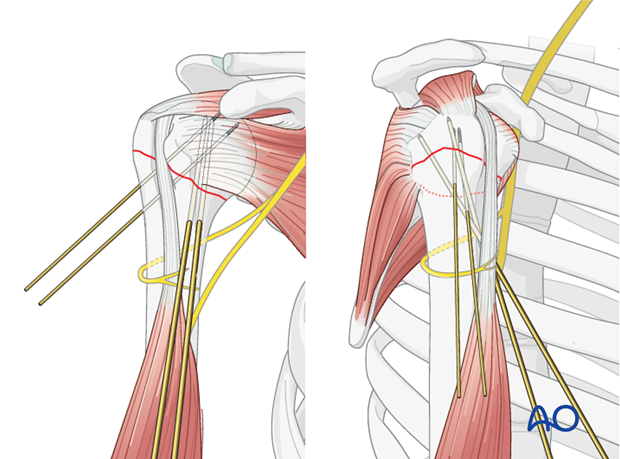

Guide wire insertion

At least two screws should be inserted to fix the fracture. Therefore, insert guide wires at the foreseen cannulated screw positions. Check the position of the guide wires by image intensification.

Note: beware the axillary nerve and the bicipital tendon.

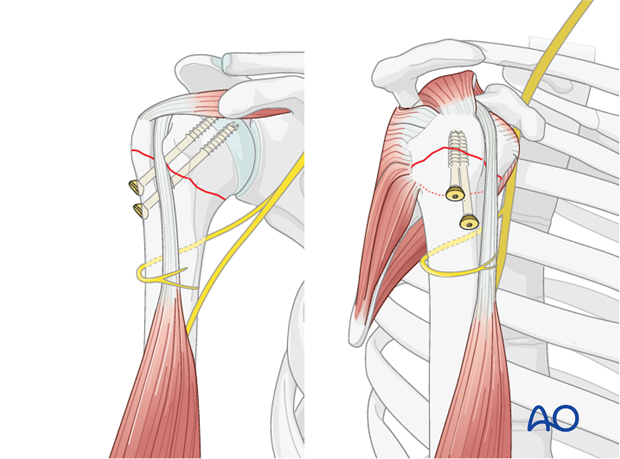

Cannulated screw insertion

Insert 3.5 mm cannulated screws of correct length over the guide wires. The screw must not perforate the articular cartilage. Use washers only in osteoporotic bone.

Remove K-wires

Remove any remaining guide and K-wires. Close wounds as needed.

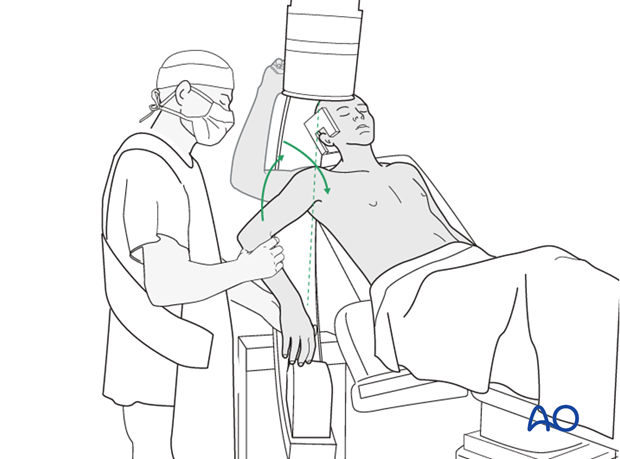

5. Final check of osteosynthesis

Using image intensification, carefully check for correct reduction and fixation (including proper implant position and length) at various arm positions. Ensure that screw tips are not intraarticular.

6. Overview of rehabilitation

The shoulder is perhaps the most challenging joint to rehabilitate both postoperatively and after conservative treatment. Early passive motion according to pain tolerance can usually be started after the first postoperative day - even following major reconstruction or prosthetic replacement. The program of rehabilitation has to be adjusted to the ability and expectations of the patient and the quality and stability of the repair. Poor purchase of screws in osteoporotic bone, concern about soft-tissue healing (eg tendons or ligaments) or other special conditions (eg percutaneous cannulated screw fixation without tension-absorbing sutures) may enforce delay in beginning passive motion, often performed by a physiotherapist.

The full exercise program progresses to protected active and then self-assisted exercises. The stretching and strengthening phases follow. The ultimate goal is to regain strength and full function.

Postoperative physiotherapy must be carefully supervised. Some surgeons choose to manage their patient’s rehabilitation without a separate therapist, but still recognize the importance of carefully instructing and monitoring their patient’s recovery.

Activities of daily living can generally be resumed while avoiding certain stresses on the shoulder. Mild pain and some restriction of movement should not interfere with this. The more severe the initial displacement of a fracture, and the older the patient, the greater will be the likelihood of some residual loss of motion.

Progress of physiotherapy and callus formation should be monitored regularly. If weakness is greater than expected or fails to improve, the possibility of a nerve injury or a rotator cuff tear must be considered.

With regard to loss of motion, closed manipulation of the joint under anesthesia, may be indicated, once healing is sufficiently advanced. However, the danger of fixation loosening, or of a new fracture, especially in elderly patients, should be kept in mind. Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions or even open release and manipulation may be considered under certain circumstances, especially in younger individuals.

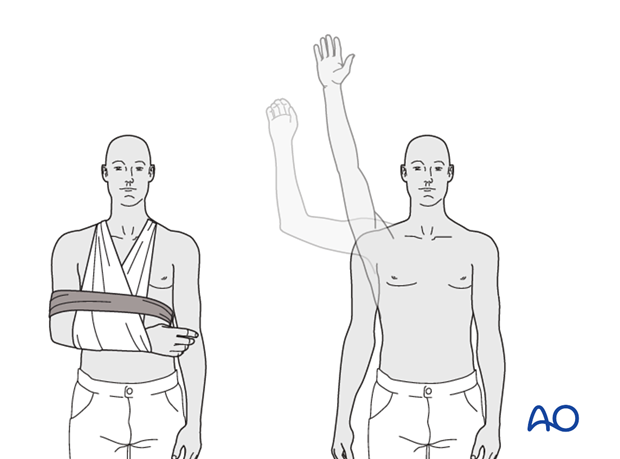

Progressive exercises

Mechanical support should be provided until the patient is sufficiently comfortable to begin shoulder use, and/or the fracture is sufficiently consolidated that displacement is unlikely.

Once these goals have been achieved, rehabilitative exercises can begin to restore range of motion, strength, and function.

The three phases of nonoperative treatment are thus:

- Immobilization

- Passive/assisted range of motion

- Progressive resistance exercises

Immobilization should be maintained as short as possible and as long as necessary. Usually, immobilization is recommended for 2-3 weeks, followed by gentle range of motion exercises. Resistance exercises can generally be started at 6 weeks. Isometric exercises may begin earlier, depending upon the injury and its repair. If greater or lesser tuberosity fractures have been repaired, it is important not to stress the rotator cuff muscles until the tendon insertions are securely healed.

Special considerations

Glenohumeral dislocation: Use of a sling or sling-and-swath device, at least intermittently, is more comfortable for patients who have had an associated glenohumeral dislocation. Particularly during sleep, this may help avoid a redislocation.

Weight bearing: Neither weight bearing nor heavy lifting are recommended for the injured limb until healing is secure.

Implant removal: Implant removal is generally not necessary unless loosening or impingement occurs. Implant removal can be combined with a shoulder arthrolysis, if necessary.

Shoulder rehabilitation protocol

Generally, shoulder rehabilitation protocols can be divided into three phases. Gentle range of motion can often begin early without stressing fixation or soft-tissue repair. Gentle assisted motion can frequently begin within a few weeks, the exact time and restriction depends on the injury and the patient. Resistance exercises to build strength and endurance should be delayed until bone and soft-tissue healing is secure. The schedule may need to be adjusted for each patient.

Phase 1 (approximately first 3 weeks)

- Immobilization and/or support for 2-3 weeks

- Pendulum exercises

- Gently assisted motion

- Avoid external rotation for first 6 weeks

Phase 2 (approximately weeks 3-9)

If there is clinical evidence of healing and fragments move as a unit, and no displacement is visible on the x-ray, then:

- Active-assisted forward flexion and abduction

- Gentle functional use week 3-6 (no abduction against resistance)

- Gradually reduce assistance during motion from week 6 on

Phase 3 (approximately after week 9)

- Add isotonic, concentric, and eccentric strengthening exercises

- If there is bone healing but joint stiffness, then add passive stretching by physiotherapist