External fixation and traction

1. Introduction

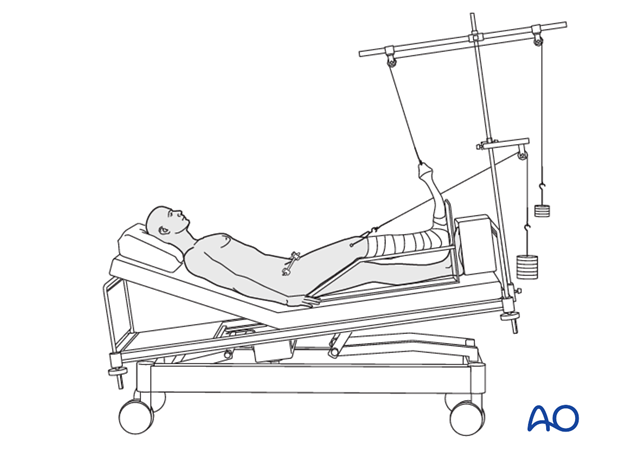

In extensive vertical displacement, longitudinal traction is advisable as initial treatment. If a definite treatment is not available, it may also be used as a definite treatment.

In this case appropriate nursing is essential to prevent pressure wounds and good respiratory and musculo-skeletal physiotherapy to avoid pulmonary complications.

It is clear that immediate pelvic splinting is beneficial, by its ability to reduce bleeding from the unstable pelvis. But, a pelvic binder cannot maintain pelvic alignment until healing is advanced. Until bony stability is obtained with external fixation, a pelvic binder or wrap is advisable to minimize ongoing bleeding.

The long term outcome of significant pelvic ring injuries is often poor. Deformity, failure to heal satisfactorily and related disability are best avoided by anatomic reduction and stable fixation. Additional advantages of stable fixation are relief of pain and early mobilization. When the necessary resources are available, this is achievable for most pelvic ring injuries.

Optimal treatment requires detailed diagnostic imaging, an advanced surgical suite and specialized instruments and implants. When these are not available, the surgeon is still faced with the challenge of obtaining and maintaining the best reduction possible. Instead of accepting deformity, pelvic external fixation with traction is suggested as the most appropriate alternative.

In most resource limited settings, the possibility of placing a pelvic external fixator is, or can be made, available. This may provide adequate control of pelvic alignment during bed rest.

Unfortunately, an external fixator, applied anteriorly, does not control posterior instability in C-type pelvic ring injuries, with complete posterior arch disruption. However, additional skeletal traction can supplement an anterior fixator and improve maintenance of overall pelvic alignment. This is why external fixation should be supplemented for treating unstable pelvic ring injuries.

Choice of external fixation

We recommend the use of an iliac crest based external fixator for this technique.

External fixator pins can be placed securely in the iliac crest with limited open exposure, but supra acetabular pins require C-arm fluoroscopy satisfactory pin placement.

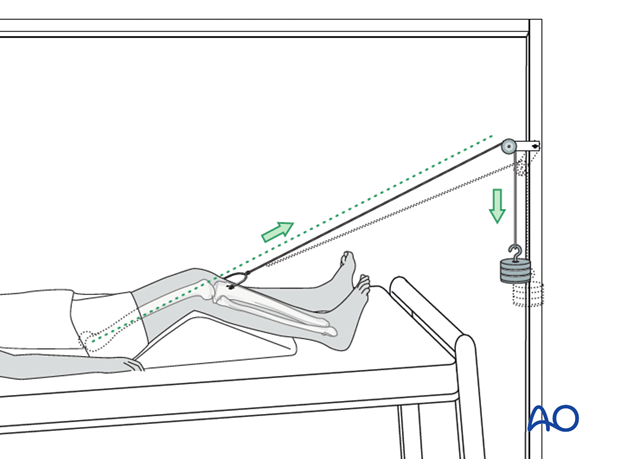

Choice of traction

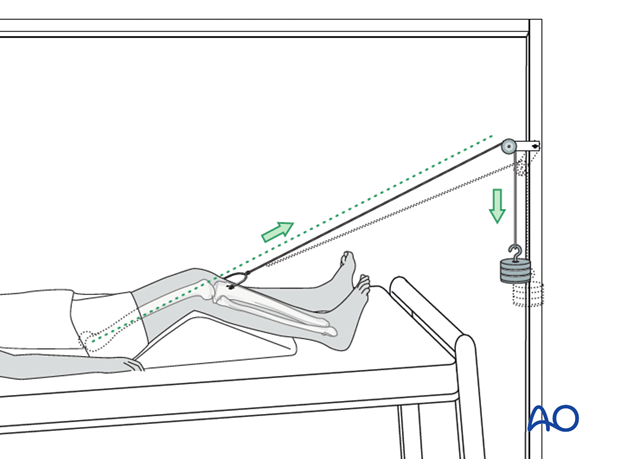

Counteract the deforming forces produced by even limited activities of a bed-bound patient, requires weights of 7 – 12 kg, depending of patient size and pelvic deformity. This above the tolerable limit for skin traction. Skeletal traction can be applied to the lower extremities through a pin in the distal femur, or tibial tubercle (as illustrated), as long there is no significant knee joint injury.

Distal displacement of an unstable hemipelvis is unusual, but if it is present, skeletal traction should not be applied as this will increase the deformity.

2. Traction

Preparation

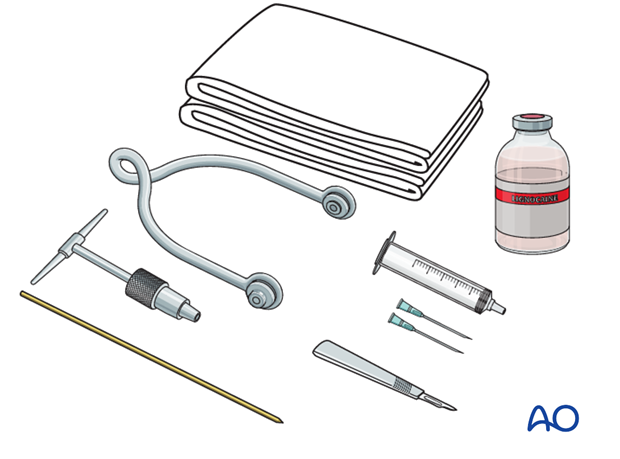

Pack with:

- Sterile towels

- Disinfectant

- Syringe

- Needles

- Local anaesthetic

- Scalpel with pointed blade

- Sharp pointed Steinmann pin, or Denham pin

- Jacobs chuck with T-handle

- Stirrup

Anesthesia

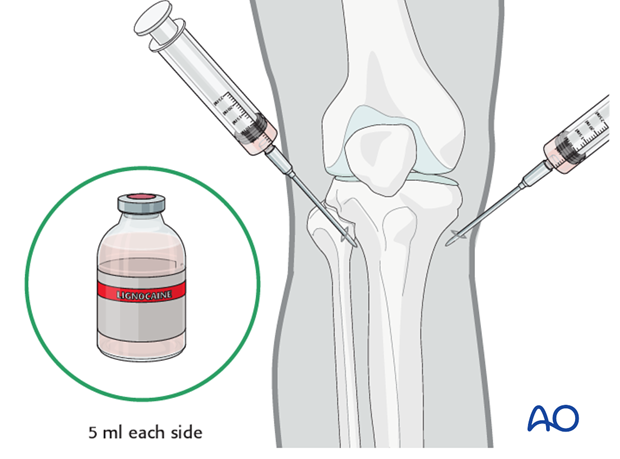

After painting the skin with antiseptic and draping with sterile towels, inject a bolus of local anaesthesia (5 ml of 2% lignocaine) on each side of the tibial tuberosity, into the lateral skin at the proposed site of pin insertion and medially at the anticipated exit point, infiltrating down to the periosteum.

Pin insertion

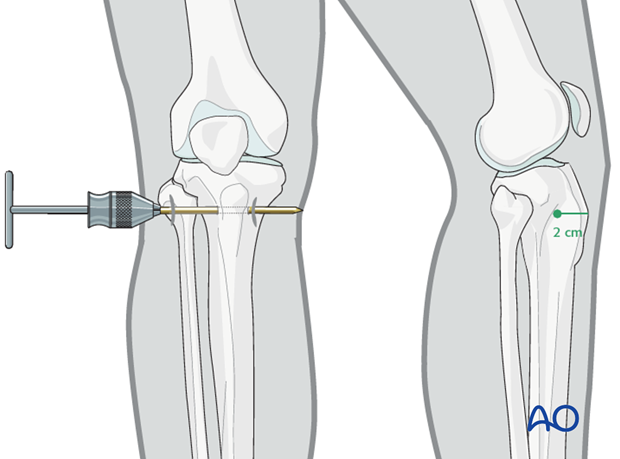

At the entry point, a stab incision is made through the skin with a pointed scalpel.

A Steinmann, or preferably a Denham pin, mounted in the T-handle, is inserted manually at a point about 2 cm dorsal to the tibial tuberosity.

As the pin is felt to penetrate the far cortex, check that the exit will coincide with the area of local anaesthetic infiltration. If not, inject additional local anaesthetic. Once the point of the pin clearly declares its exit site, make a small stab incision in the overlying skin.

Once the pin is in place, ensure that there is no tension on the skin at the entry and exit points. If there is, then a small relieving incision may be necessary.

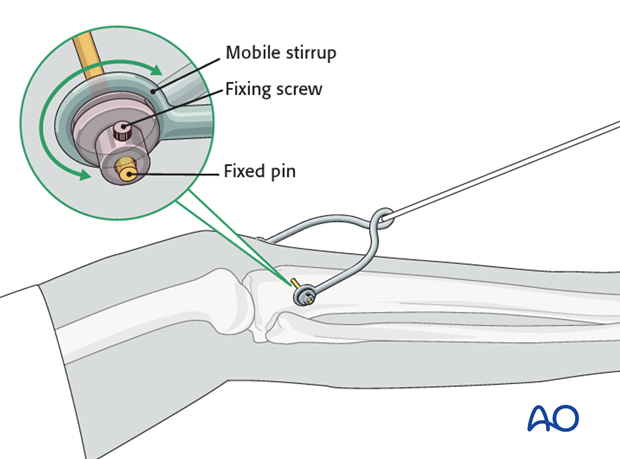

It is important that the stirrup be freely mobile around the traction pin, to prevent rotation of the pin within the bone. Rotating pins loosen quickly and significantly increase the risk of pin track infection.

Pin care

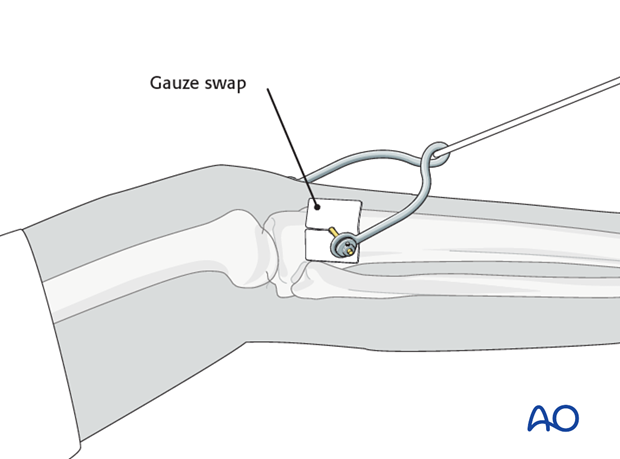

In order to prevent pin track infection, apply a slit gauze swab around the pin and do not remove the crust that develops around the pin on the skin. The gauze swab should only be changed infrequently.

Reduction

It is important that the surgeon apply external fixation with the best possible closed reduction as soon as possible after the patient's injury and initial stabilization. Pelvic alignment should be assessed with X-rays of the full pelvis while the patient is in bed, in traction. In addition to an AP X-ray, inlet and outlet oblique views are necessary to assess degree of displacement.

Typically unstable pelvic ring injuries result in displacement of the unstable hemipelvis posteriorly and cranially. External rotation, through disruption of the anterior pelvic arch can usually be reduced by external fixation. Manipulation using the external fixator pins can often improve posterior pelvic alignment as well.

3. Postoperative care

During the first 2-3 weeks, pelvic instability is greatest, loss of an initially satisfactory reduction may occur.

Frequent follow up X-rays allow this to be recognized and corrected.

Bony pelvic injuries are usually fairly well consolidated by 6 weeks.

Purely ligamentous injuries such as sacroiliac joint or pubic symphysis may require 8-12 weeks before late progression of deformity becomes likely.

Once the pelvis has consolidated, and the patient is more comfortable with callus visible on X-rays, progressive mobilization may begin. Weight bearing should initially be limited on the unstable side if possible.