ORIF - Pubic ramus screw

1. Introduction

Operative treatment of pubic rami fractures

Fractures of the pubic rami are nearly always associated with further pelvic ring injuries.

The treatment of these fractures is guided by the displacement and other associated pelvic ring injuries.

In many cases, a strong periosteum, the inguinal ligament and the pectineal ligament will provide adequate stability and no additional treatment is required.

With more complex, unstable pelvic ring injuries, ramus fractures may require fixation to restore stability and promote healing.

The decision for operative vs. nonoperative is best made by evaluating the entire pelvic ring and its stability instead of focussing only on the ramus fracture.

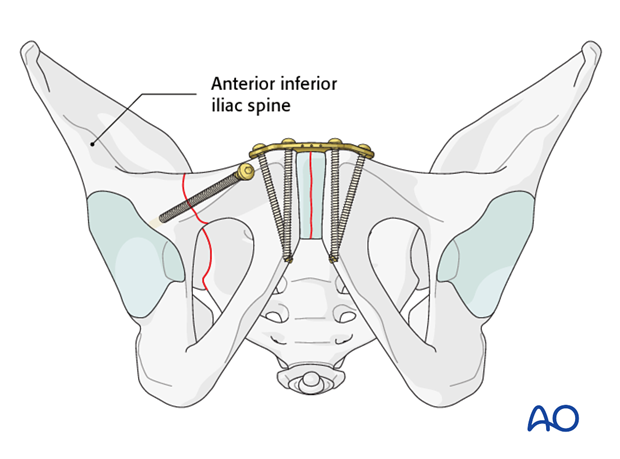

For more complex injuries, posterior reduction and fixation must precede fixation of the ramus fractures. In these cases, the anterior fixation supplements and stabilizes the posterior fixation.

Options for fixation

Stabilization of ramus fractures can be performed by a variety of techniques:

- Internal fixation with an intramedullary screw

- Internal fixation with a plate

- Indirect stabilization with external fixation

Intramedullary screw fixation of ramus fractures is a form of anterior fixation that provides stability and can be inserted using either open or percutaneous techniques.

The decision to use this technique is based on the pelvic injury pattern, soft tissue, and the surgeons comfort with the anatomy and imaging.

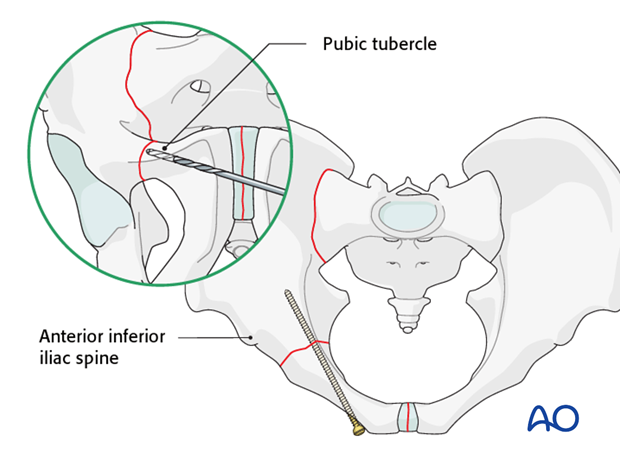

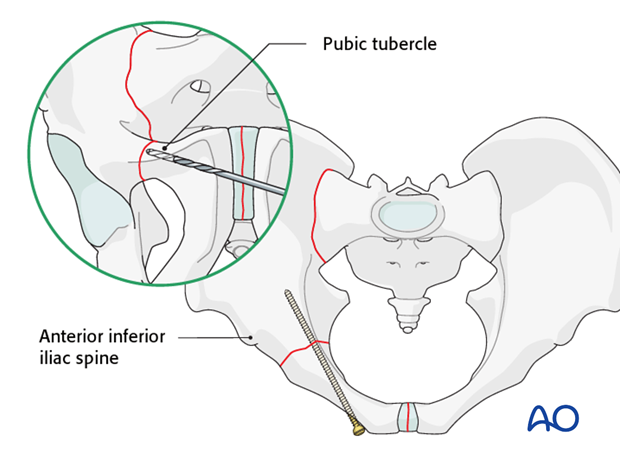

Percutaneous screws insertion sites

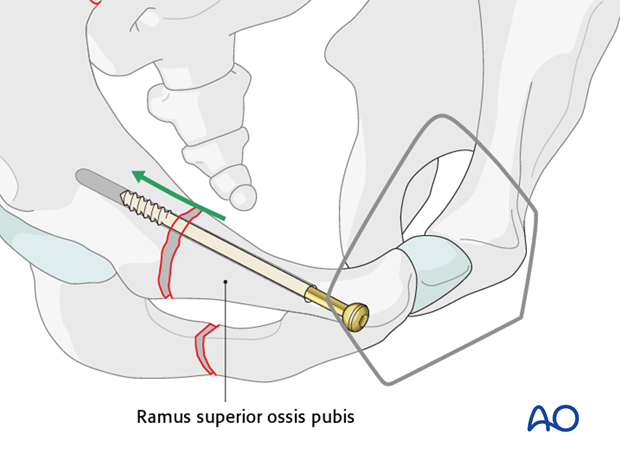

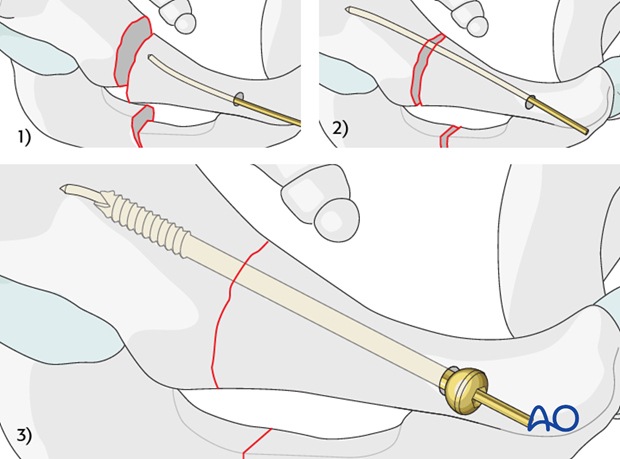

Intramedullary pubic ramus screws can be placed retrograde or antegrade through percutaneous stab wounds.

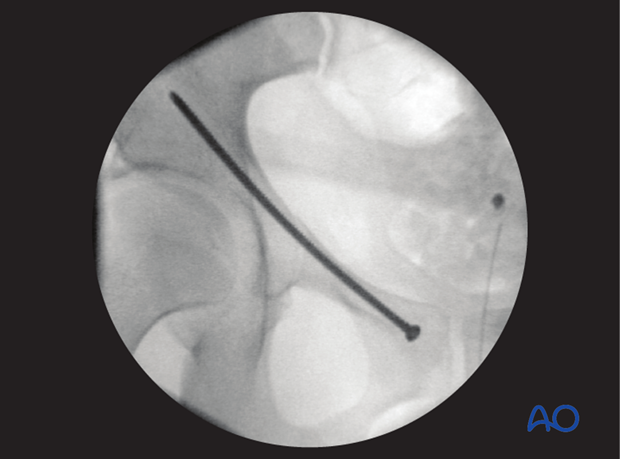

Retrograde screws, from the pubis laterally, are inserted through an incision made over the contralateral pubic tubercle. C-arm fluoroscopy is essential to define the starting point and passage of drill bit and screw within the superior pubic ramus, across the fracture, and cephalad to the acetabulum. The inlet and obturator outlet views are essential for confirming proper screw placement.

For more lateral fractures, an antegrade screw may be inserted from a stab wound cephalad to the hip joint along the same trajectory as the retrograde screw, but in the opposite direction.

2. Patient preparation

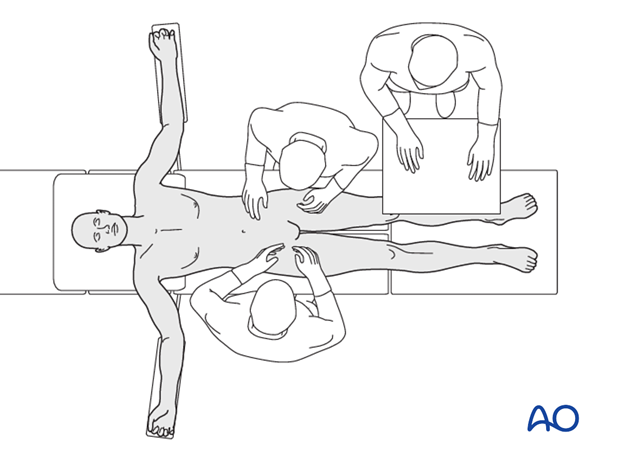

This procedure is performed with the patient in a supine position.

3. Reduction

Reduction of the pelvic ring must be achieved prior to insertion of the intramedullary screw. It is important to understand that the screw functions simply to hold the reduction but in most cases does not achieve the reduction.

Reduction can be achieved by either closed or open methods.

Closed reduction

Closed reduction of ramus fractures typically requires reduction of the overall pelvic ring. In cases with displaced posterior ring injuries, reduction of the posterior ring may help to indirectly reduce the ramus fractures.

Other methods of closed reduction include percutaneous manipulation of the pelvic ring using Schanz screws. After reduction is achieved (verified by X-ray), the reduction may be held by an adjacent K-wire or external fixator during screw insertion.

A fracture gap in the ramus may be reduced by inserting a partially threaded lag screw. As the screw is tightened, the gap is closed.

Small amounts of displacement may be able to be reduced using cannulated screws. In these cases, a gently curved guide wire is used to traverse the mildly displaced fracture. Once the screw is inserted over the guide wire the fracture is indirectly reduced by screw insertion.

The K-wire should be removed once the screw is sufficiently past the fracture line.

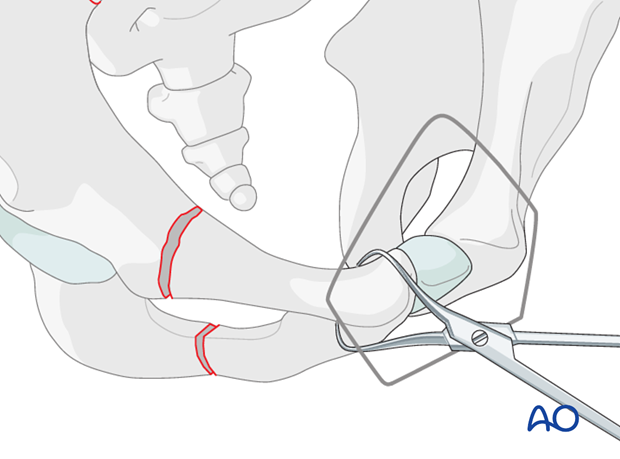

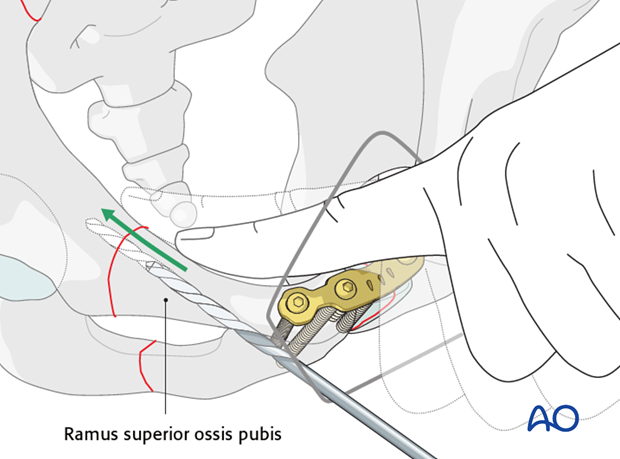

Open reduction

The medial aspects of the superior pubic rami are exposed using an extended Pfannenstiel approach.

After exposure, the fracture may be directly manipulated with bone holding forceps.

Note

Be alert for rotational malalignment of the fracture. This can be corrected by derotation by bone holding forceps.

4. Screw insertion

Determine the type of screw

The type of screw that is chosen for fixation depends on the fracture pattern, location, patient's size and anatomy, and surgeon's preference.

Screws that are commonly used are:

- 3.5 mm cortical screws

- 4.5 mm cortical screws

- 6.5 or 7.3 mm cancellous screws

Cannulated screws as described above are also advantageous.

Screw entry point

Intramedullary screws for fixation of ramus fractures may be inserted in an antegrade or retrograde fashion.

The choice of the direction of insertion depends on the location of the fracture and surgeon's preference. Ramus fractures that are located closer to the pubic symphysis are often easier to reduce and control using a retrograde screw. In contrast more proximal ramus fractures are better stabilized with an antegrade screw.

Retrograde screw

Choose the entry point caudal to the pubic tubercle as lateral as possible to optimize the screw direction in respect to the fracture line.

The screw is directed proximal and superior to avoid the acetabulum.

Check the orientation

The direction of the screw is determined using X-ray guidance. If an open technique is used for a retrograde screw, then check the orientation with the index finger along the inner side of the pubic ramus, as illustrated.

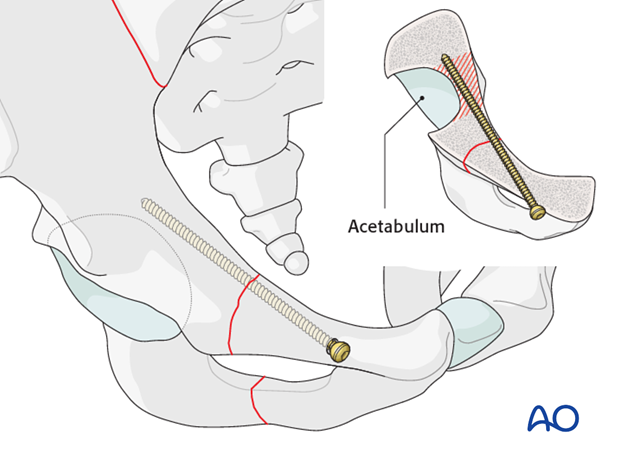

Proximity to the hip joint

Whether inserting a retrograde or an antegrade screw, great care must be taken to prevent the screws from penetrating the hip joint.

The cross section of the anatomic model shows the correct screw position in the anterior column across the fracture side.

It displays the close relationship of the implant to the joint.

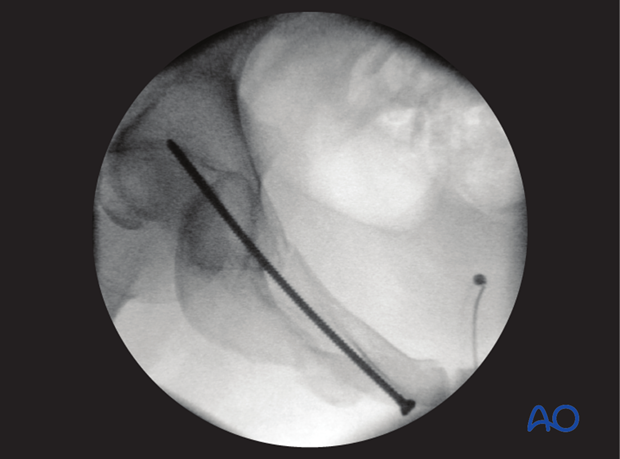

Drilling and length measurement

The type of drill used will depend on the diameter of screw chosen. The drill is observed using X-ray guidance as it is carefully advanced. Unless the bone is very hard, only the near cortex needs to be drilled, as the screw will advance through the cancellous bone by itself.

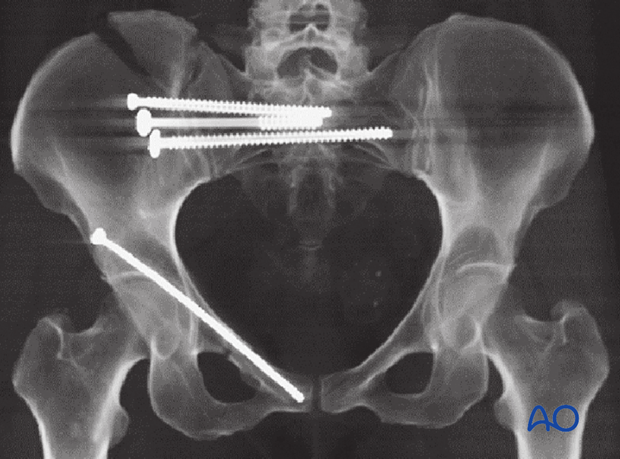

Multiple X-ray views are obtained intraoperatively to ensure that the screw does not penetrate the acetabulum and remains safely within the bone (inlet view, obturator oblique view).

The inlet view is used to ensure that the drill and later the screw do not penetrate the inner cortex of the ramus.

The obturator oblique view is used to ensure that the drill and later the screw do not penetrate the acetabulum.

A depth gauge could be used to measure the length of the screw.

When cannulated screws are used, the guide wire is used to determine the length and the position of the screw.

5. Post-operative X-rays

At the completion of fixation, it is necessary to obtain AP, inlet, and outlet X-ray views of the pelvic ring, and obturator and iliac oblique views to ensure the acetabulum is not penetrated by the screw.

6. Aftercare following open reduction and fixation

Postoperative blood test

After pelvic surgery, routine hemoglobin and electrolyte check out should be performed the first day after surgery and corrected if necessary.

Bowel function and food

After extensile approaches in the anterior pelvis, the bowel function may be temporarily compromised. This temporary paralytic ileus generally does not need specific treatment beyond withholding food and drink until bowel function recovers.

Analgesics

Adequate analgesia is important. Non pharmacologic pain management should be considered as well (eg. local cooling and psychological support).

Anticoagulation

Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus is routine unless contraindicated. The optimal duration of DVT prophylaxis in this setting remains unproven, but in general it should be continued until the patient can actively walk (typically 4-6 weeks).

Drains

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Wound dressing

Dressings should be removed and wounds checked after 48h, with wound care according to surgeon's preference.

Physiotherapy

The following guidelines regarding physiotherapy must be adapted to the individual patient and injury.

It is important that the surgeon decide how much mechanical loading is appropriate for each patient's pelvic ring fixation. This must be communicated to physical therapy and nursing staff.

For all patients, proper respiratory physiotherapy can help to prevent pulmonary complications and is highly recommended.

Upper extremity and bed mobility exercises should begin as soon as possible, with protection against pelvic loading as necessary.

Mobilization can usually begin the day after surgery unless significant instability is present.

Generally, the patient can start to sit the first day after surgery and begin passive and active assisted exercises.

For unilateral injuries, gait training with a walking frame or crutches can begin as soon as the patient is able to stand with limited weight bearing on the unstable side.

In unstable unilateral pelvic injuries, weight bearing on the injured side should be limited to "touch down" (weight of leg). Assistance with leg lifting in transfers may be necessary.

Progressive weight bearing can begin according to anticipated healing. Significant weight bearing is usually possible by 6 week but use of crutches may need to be continued for three months. It should remembered that pelvic fractures usually heal within 6-8 weeks, but that primarily ligamentous injuries may need longer protection (3-4 months).

Fracture healing and pelvic alignment are monitored by regular X-rays every 4-6 weeks until healing is complete.

Bilateral unstable pelvic fractures

Extra precautions are necessary for patients with bilaterally unstable pelvic fractures. Physiotherapy of the torso and upper extremity should begin as soon as possible. This enables these patients to become independent in transfer from bed to chair. For the first few weeks, wheelchair ambulation may be necessary. After 3-4 weeks walking exercises in a swimming pool are started.

After 6 weeks, if pain allows, the patient can start walking with a three point gait, with less weight bearing on the more unstable side.

Full weight bearing is possible after complete healing of the bony or ligamentous legions, typically not before 12 weeks.