Splint immobilization

1. General considerations

Introduction

Some undisplaced fractures may be treated nonoperatively with the limb supported in a sling with a splint. This particularly applies to low-demand patients.

Closed reduction and splinting is also indicated as a temporary treatment in displaced fractures where the skin or neurovascular structures are potentially compromised by interfragmentary movements.

This could be as a definitive treatment in appropriate patients or as a preliminary measure prior to internal fixation.

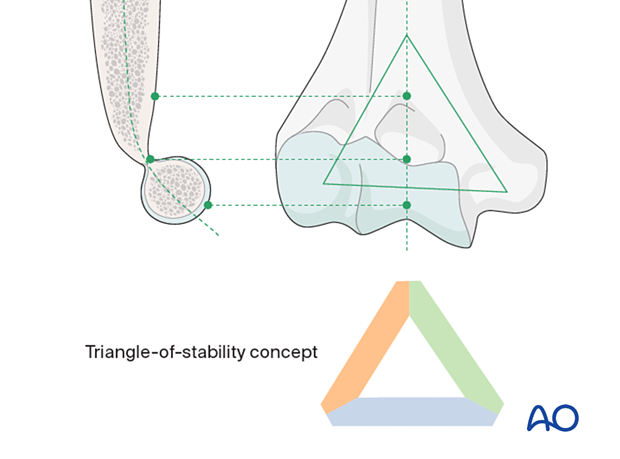

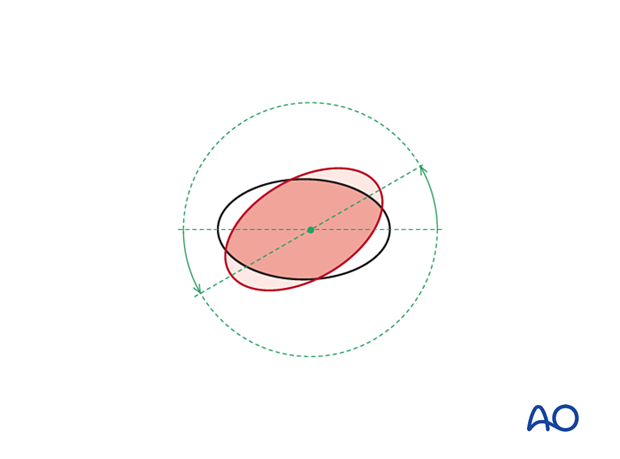

Triangle-of-stability concept

The mechanical properties of the distal humerus are based on a triangle of stability, comprising the medial and lateral columns and the articular block (see also the anatomical concepts).

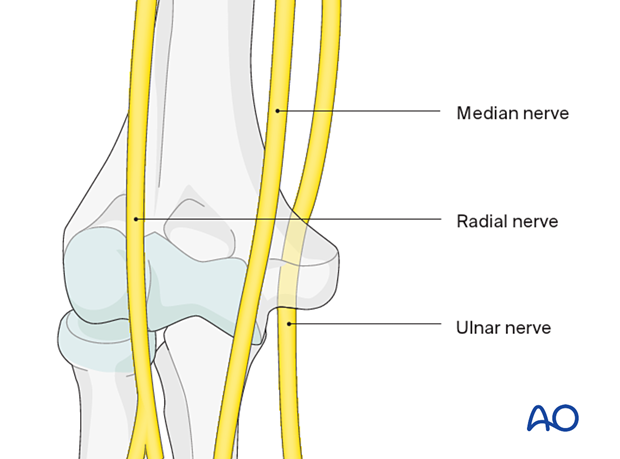

Nerves around the distal third of the humerus

Be aware that the patient may still develop neurologic problems even when treated nonoperatively. This is particularly relevant to the ulnar nerve.

See also the additional material on neurological protection and handling.

Complications

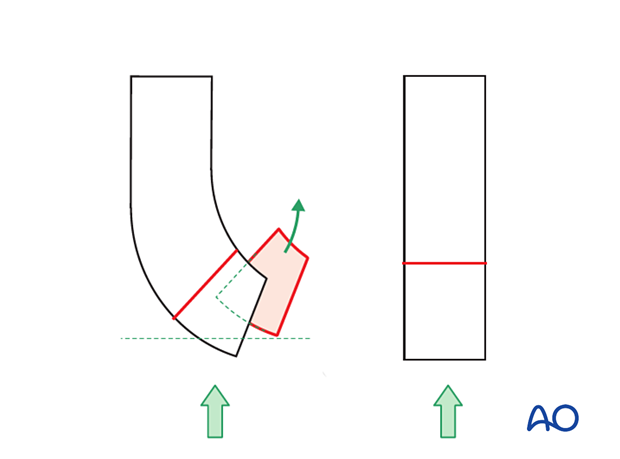

Tendency to malalignmentThere is a tendency for malalignment and secondary anterior displacement.

In oblique fractures, translation can occur in the coronal plane.

Similarly, there is the risk of rotation and rotational malposition of the fragments. Reduction is made more difficult by the weight of the forearm acting on the fracture site.

Healing with any deformity (angulation, malrotation, or shortening) may cause significant elbow dysfunction, but this may be well tolerated in low-demand patients.

Swelling will occur due to bruising and soft-tissue damage. Be mindful of neurovascular compromise or compartment syndrome.

2. Reduction

If a displaced fracture is to be treated nonoperatively, reduce the fracture in a timely manner.

Perform the reduction under general or regional anesthesia.

Reduction of articular fragments is usually not possible due to swelling. It should aim for overall alignment of the upper limb and restoration of length.

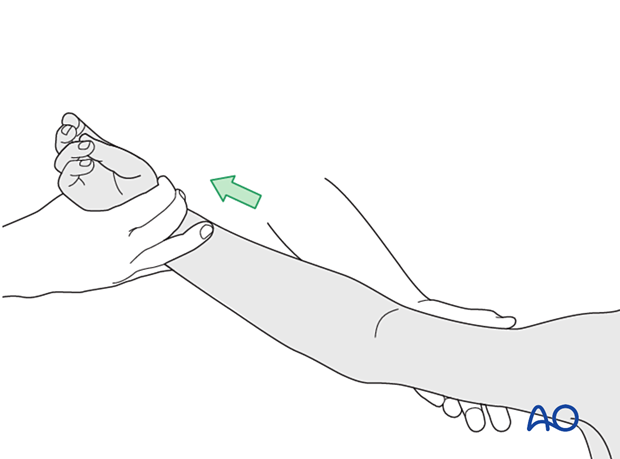

Apply gentle manual traction to the arm with one hand and palpate with the other hand the bony eminences of the distal humerus, ie, medial and lateral epicondyles.

Verify the length restoration of the fracture with image intensification.

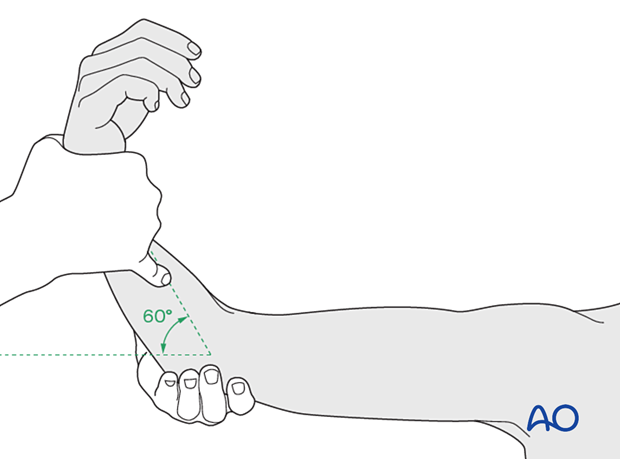

Flex the elbow up to 45°–60° while maintaining the distraction the whole time - as the elbow flexes, the reducing hand also applies distraction.

3. Splint application

Application of cast padding

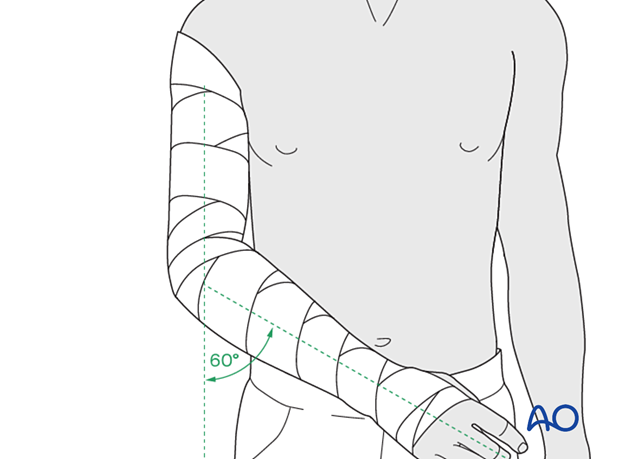

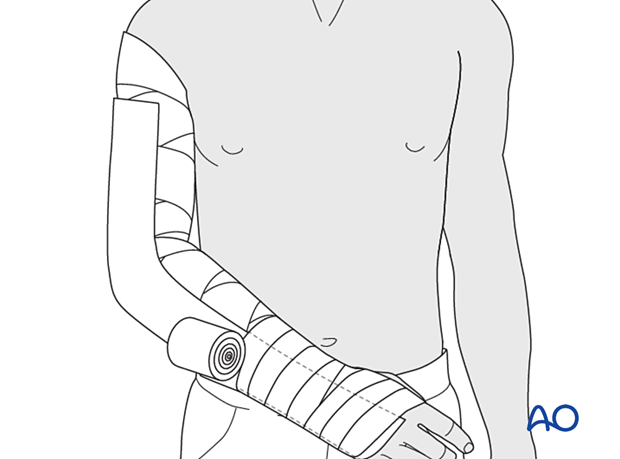

With the patient sitting, if possible, wrap cast padding around the upper arm, elbow, forearm, and hand, down as far as the transverse crease of the hand (leave the MCP joints free). Keep the elbow flexed and the forearm in neutral rotation. Make sure that the epicondyles of the humerus and the antecubital area are well padded.

Application of the splint

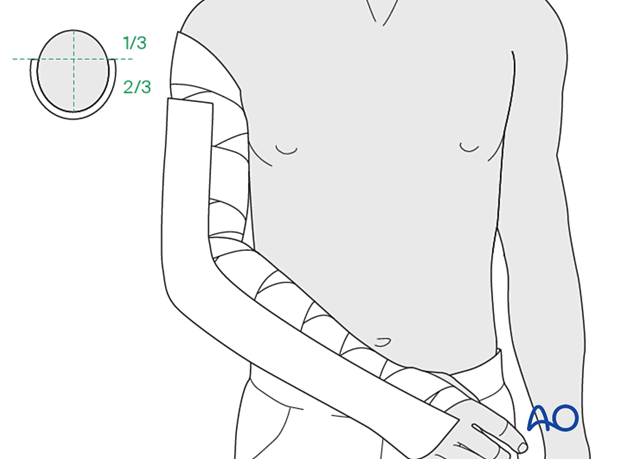

Apply a splint of fiberglass or plaster on the posterior aspect of the arm and forearm. It should be wide enough to cover more than half of the circumference of the arm and forearm.

Secure the splint with an elastic bandage that should not be too tight.

Sling support

The injured arm is supported in an appropriate sling.

4. Aftercare

Immediate aftercare

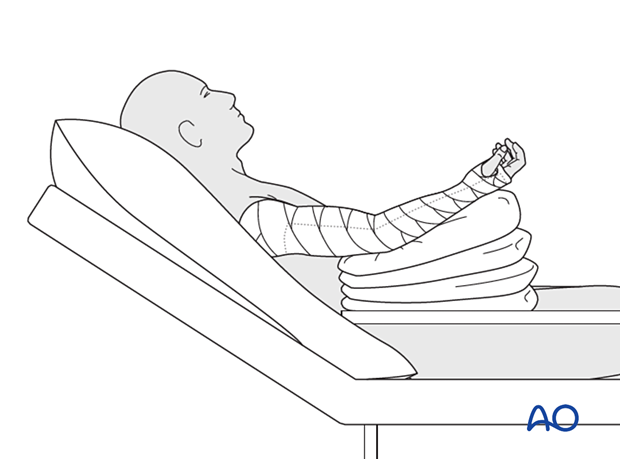

Analgesia may be necessary. The patient is usually more comfortable in a sitting or semireclining position, with the elbow elevated, preferably above the chest, on pillows at least for the first few weeks. Fragment motion and crepitus may well be perceived, and the patient should be reassured that this is normal, stimulates healing, and will gradually settle.

Observations of the perfusion and passive movement of the hand are made frequently, particularly if a nerve block has been used for pain relief, to regularly evaluate the potential risk of compartment syndrome.

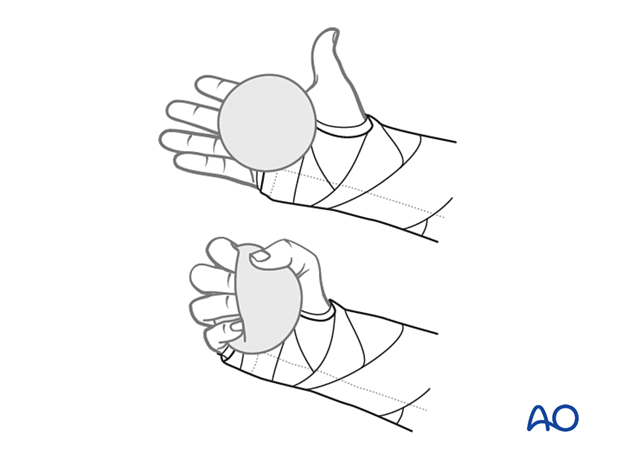

Hand pumping and finger motion exercises are started as soon as possible to reduce lymphedema and to improve venous return in the limb. This helps to reduce postoperative swelling.

Follow-up

According to fracture complexity and patient needs for follow-up examination and x-rays, the patient is seen in regular time intervals until union is secure and full functional range of motion and strength have returned.

Mobilization

Once there is sufficient fracture healing based on clinical and radiographic examination, mobilization may be initiated.

For exercises, the splint is removed.

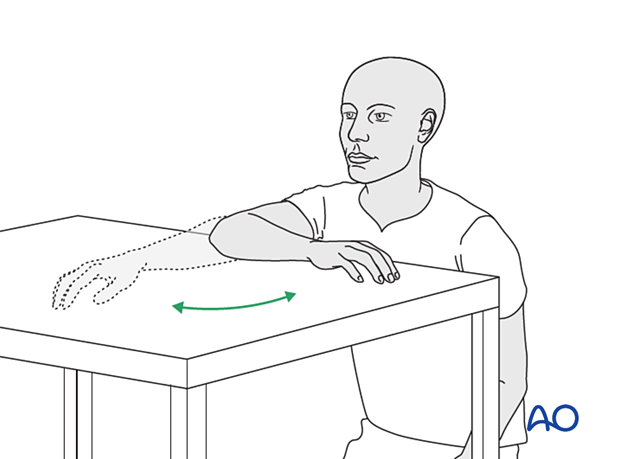

Gravity-eliminated active assisted exercises of the elbow are used, as the elbow is prone to stiffness:

- The arm is rested on a side table

- Flexion/extension of the arm at the elbow is encouraged in a gentle sweeping movement on the tabletop as far as comfort permits

- Maintain arm in the anatomical flexion-extension plane. Avoid the arm in the varus position

- Exercises are performed hourly in repetitions, the number of which is governed by comfort

- Between periods of exercise, the elbow is rested in the elevated position or replaced in the sling for comfort

A simple elastic noncompressive sleeve dressing can be helpful for edema reduction.

Gravity-eliminated active-assisted elbow motion exercises are continued.

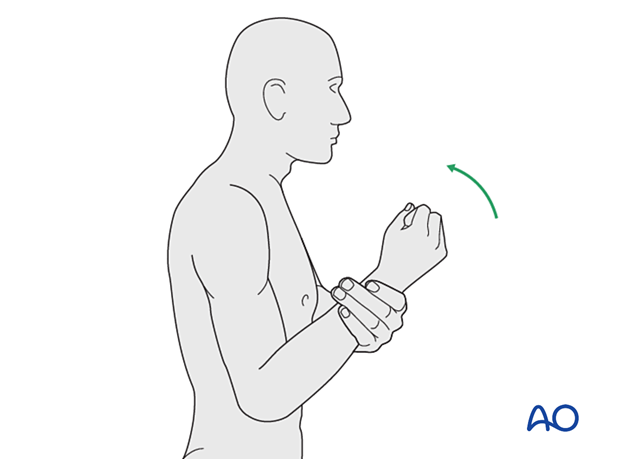

When there is radiological union, active-assisted exercises are performed by having the patient bend the elbow as much as possible using his/her muscles while simultaneously using the opposite arm to gently push the arm into further flexion. This effort should be sustained for several minutes; the longer, the better.

Next, a similar exercise is performed for extension.

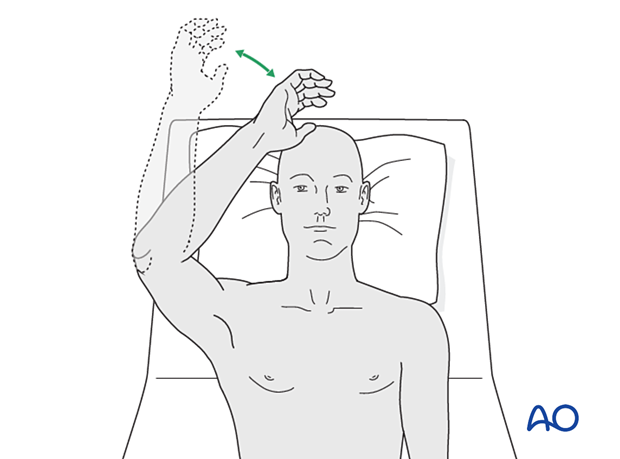

If the patient finds it difficult to accomplish these exercises when seated, then performing the same exercises when lying supine can be helpful.

Load-bearing

No load-bearing (ie, pushing, pulling, or carrying weights) or strengthening exercises are allowed until early fracture healing is established by x-ray and clinical examination.

This is usually a minimum of 8–12 weeks after injury. Weight-bearing on the arm should be avoided until bony union is assured.