Traction

1. General considerations

Distal femur fractures should only be considered for nonoperative fracture treatment if there are neither facilities, nor skills, for surgical treatment.

Nonoperative treatment means that the patient will be in some form of traction for at least 6-8 weeks, often 10-12 weeks.

Treatment by traction appears simpler than surgery. However, it requires great skill of application and constant monitoring throughout the whole treatment period.

The initial treatment is usually skin traction, later converted to skeletal traction.

Disadvantages of prolonged skin traction are:

- Loosening

- Constriction

- Friction

- Allergy

If skin traction is likely to be used for more than 24 hours, greater patient comfort and better control of the femoral fracture can be achieved by using Hamilton-Russell skin traction.

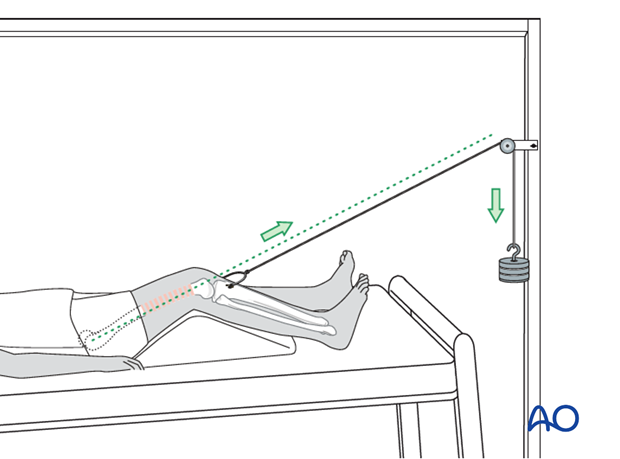

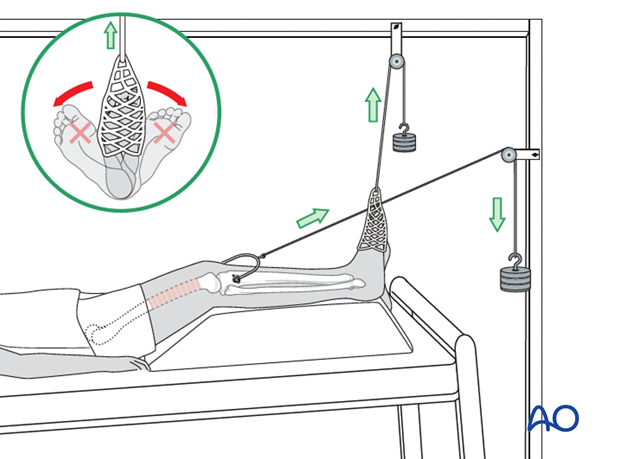

A padded sling is placed behind the slightly flexed knee and skin traction applied to the lower leg. The traction cord and pulley system are as illustrated.

The principle of the parallelogram of forces determines that the upward pull of the sling and the longitudinal pull of the skin traction create a resolution of force in the line of the femur, as illustrated.

This configuration of traction also allows control of rotation, by side-to-side adjustment of the pulley above the knee.

Complications of skeletal traction

Surgeons have moved away from skeletal traction because of multiple serious complications. These include:

- Pin tract infections

- Muscle wasting

- Prolonged bed immobilization with resultant bed sores

- Increased resource utilization (nursing care)

- Less than adequate fracture reduction

Pin tract infection - In case of pin loosening or pin tract infection, the following steps need to be taken:

- Remove all involved pins and place new pins in a healthy location.

- Debride the pin sites in the operating theater, using curettage and irrigation.

- Take specimens for a microbiological study to guide appropriate antibiotic treatment if necessary.

Muscle wasting - A patient in traction is immobilized and a patient must be educated with physiotherapy resources to consistently perform bed exercises for all muscle groups.

Prevention of bedsores - Nursing care is the hallmark of the prevention of bedsores, including regular skin checks and careful movement and attention to the posterior side of the body that is dependent.

Prolonged bed immobilization - A patient kept in bed for 12 weeks is a time consuming and expensive use of hospital resources and should only be used when there is no other option.

Poor fracture reduction - Traction provides length, but alignment and rotation are difficult to achieve accurately, often resulting in some malreduction of the femur. Late osteotomies may be needed to correct significant shortening, malalignment, or malrotation.

2. First aid

The ABC of primary care for the injured always takes precedence over the fracture treatment. Once the safety of the patient is established, attend to the femoral fracture.

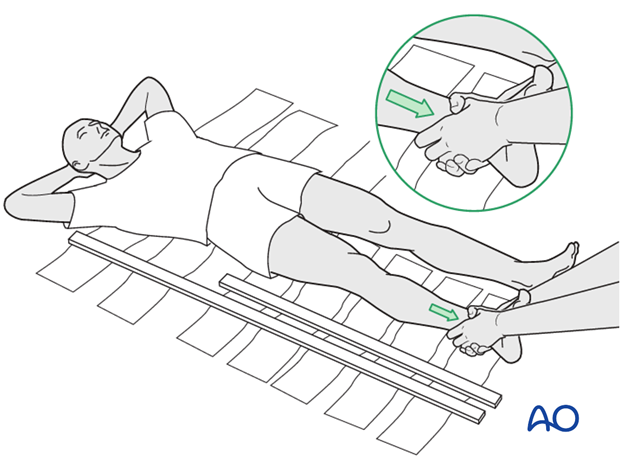

It is important in treating a femoral shaft fracture to splint the whole leg as soon as possible, and certainly before transporting the patient.

For that purpose, you need two firm boards or splints along the leg, suitably padded, one on the inner aspect of the leg and one along the leg and the body on the outer aspect.

Any soft material such as clothing, blankets, etc. can be used as emergency padding.

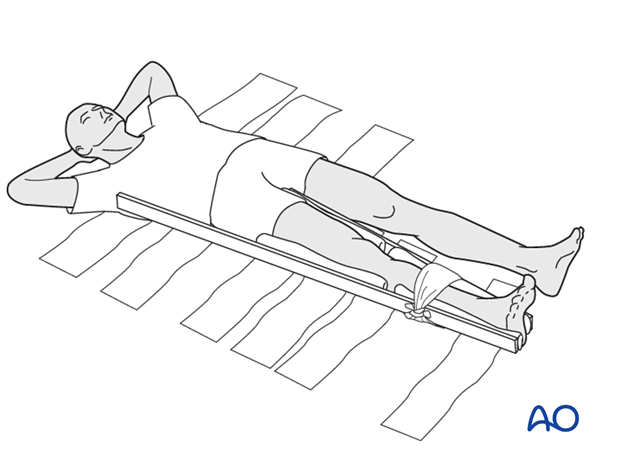

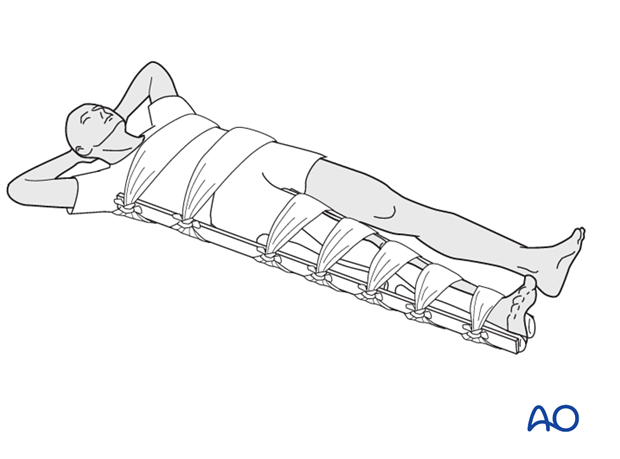

The splints should then be kept in place by bandages around both splints and ...

...the leg as well as the body.

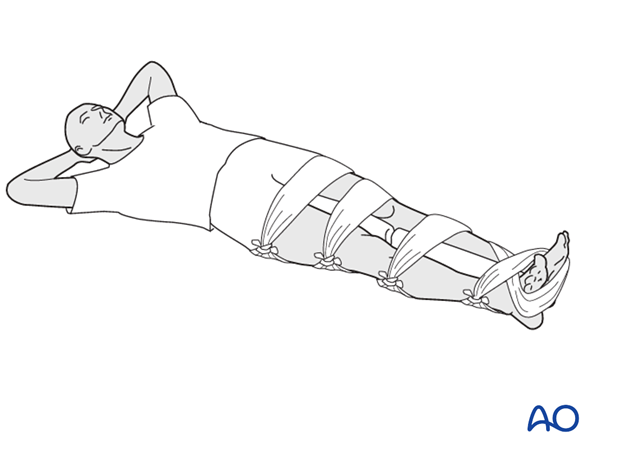

If no boards are available, some stabilization can be achieved by splinting the fractured leg to the uninjured leg, with padding in between.

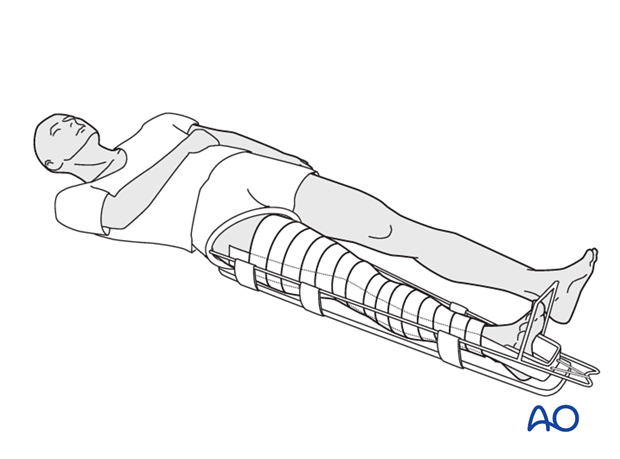

Many ambulance services these days work with technically advanced light-weight traction splints.

Another way of splinting is the use of skin traction in combination with a Thomas splint.

The Thomas splint affords excellent immobilization for transporting the patient. Unfortunately, the availability of the Thomas splint is somewhat limited.

Great care must be taken to avoid excessive pressure of the ring of the splint against the perineum, using suitable padding as necessary.

3. Skin traction

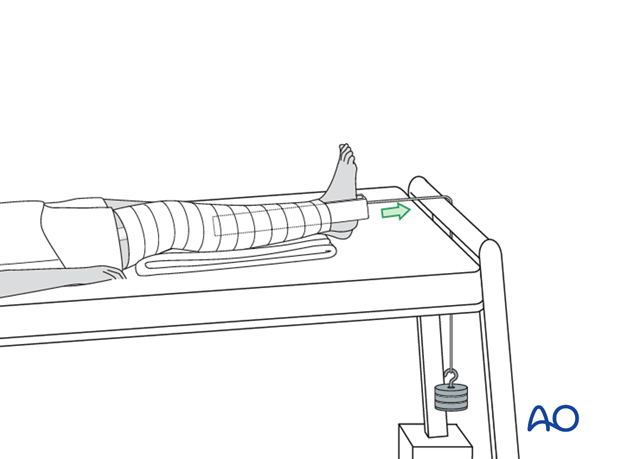

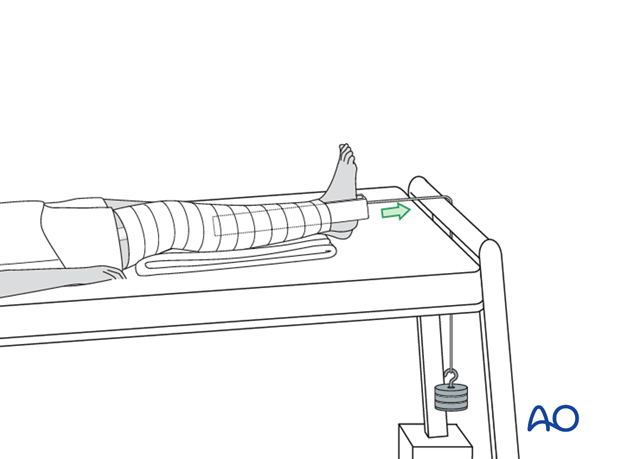

In the event that there is no Thomas splint available, skin traction over the end of the bed with 7 kg will be the initial treatment of a femoral fracture.

With the tilted bed the weight of the patient acts as counter traction.

This photograph shows a commercially available skin traction kit.

Before the application of the adhesive traction strip, the skin is painted with friar’s balsam.

The strip is then applied below the level of the fracture on the medial and lateral aspects of the leg as shown, carefully avoiding any creases.

To prevent the development of blisters, the skin traction needs to be applied without folds or creases in the adhesive material and the covering bandage should be non-elastic.

Should a crease be inevitable, due to the contour of the limb, the creased area should be lifted, partially slit transversally and the edges overlap.

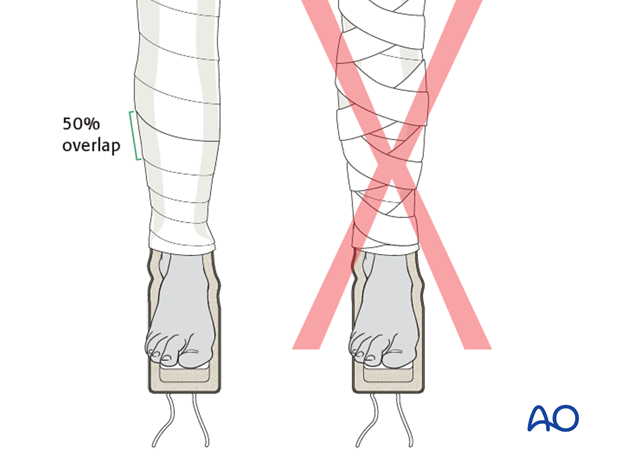

Once the adhesive strip is satisfactorily in place, ensuring that the padded lower section overlies the malleoli, a spiral inelastic bandage is carefully wrapped around the limb from just above the malleoli to the top of the strip.

Apply the overlying bandages spirally overlapping by half.

The traction strip should be applied to the level of the fracture only, but not above.

4. Skeletal traction

Skeletal traction via tibial pin (Perkin’s traction)

As soon as the decision is made that traction will be the definitive treatment, conversion to skeletal traction should be done.

Preparation

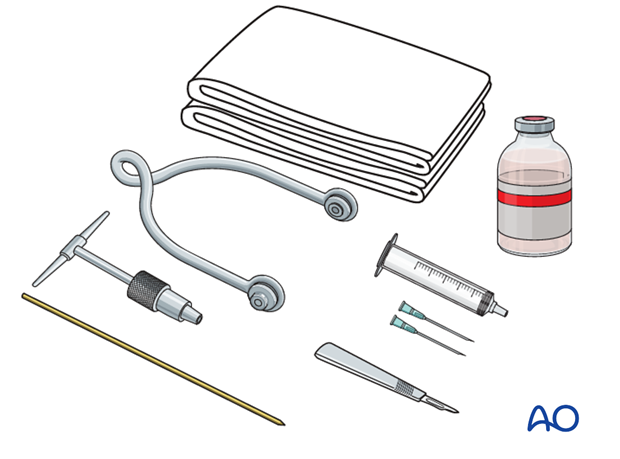

Pack with:

- Sterile towels

- Disinfectant

- Syringe

- Needles

- Local anaesthetic

- Scalpel with pointed blade

- Sharp pointed Steinmann pin, or Denham pin

- Jacobs chuck with T-handle

- Stirrup

Anesthesia

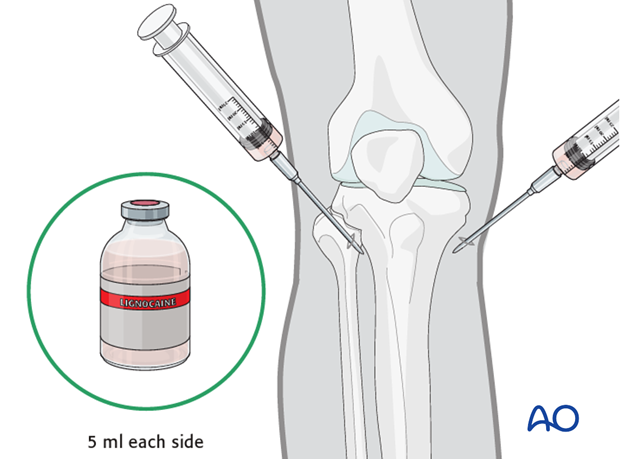

After painting the skin with antiseptic and draping with sterile towels, inject a bolus of local anaesthesia (5 ml of 2% lignocaine) on each side of the tibial tuberosity, into the lateral skin at the proposed site of pin insertion and medially at the anticipated exit point, infiltrating down to the periosteum.

Pin insertion

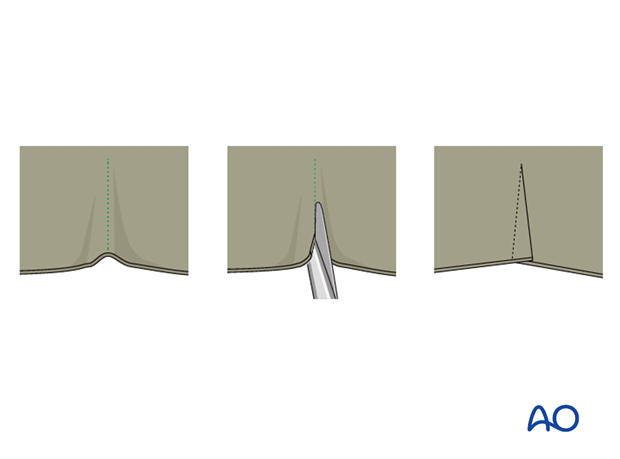

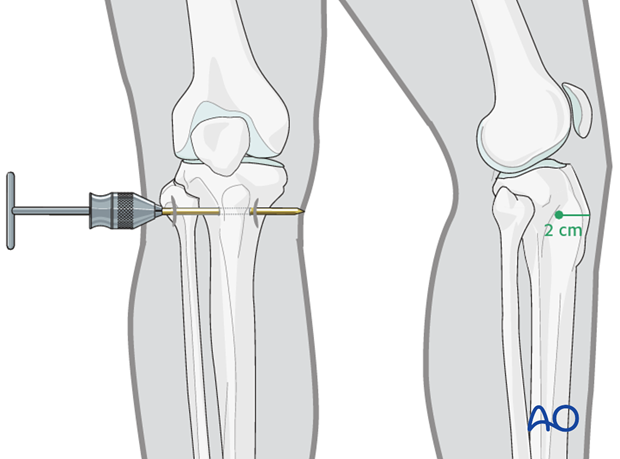

At the entry point, a stab incision is made through the skin with a pointed scalpel.

A Steinmann, or preferably a Denham pin, mounted in the T-handle, is inserted manually at a point about 2 cm dorsal to the tibial tuberosity.

As the pin is felt to penetrate the far cortex, check that the exit will coincide with the area of local anaesthetic infiltration. If not, inject additional local anaesthetic. Once the point of the pin clearly declares its exit site, make a small stab incision in the overlying skin.

Once the pin is in place, ensure that there is no tension on the skin at the entry and exit points. If there is, then a small relieving incision may be necessary.

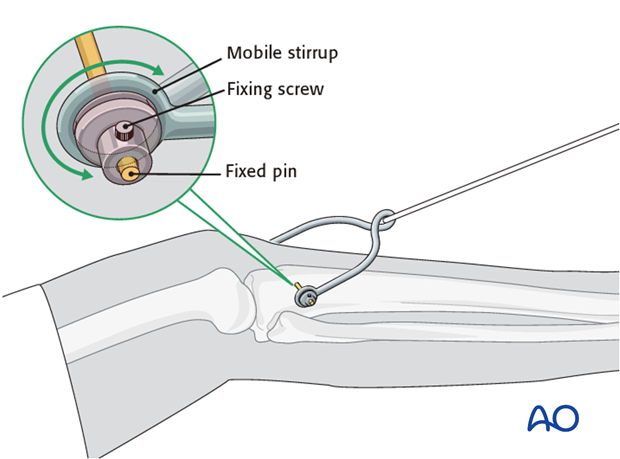

It is important that the stirrup be freely mobile around the traction pin, to prevent rotation of the pin within the bone. Rotating pins loosen quickly and significantly increase the risk of pin track infection.

Pin site care

Various aftercare protocols to prevent pin tract infection have been established by experts worldwide. Therefore, no standard protocol for pin-site care can be stated here. Nevertheless, the following points are recommended:

- The aftercare should follow the same protocol until removal of the traction.

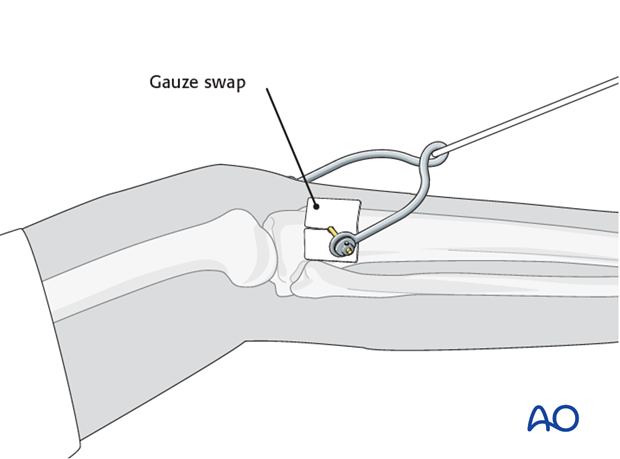

- The pin-insertion sites should be kept clean. Any crusts or exudates should be removed. The pins may be cleaned with saline and/or disinfectant solution/alcohol. The frequency of cleaning depends on the circumstances and varies from daily to weekly but should be done in moderation.

- No ointments or antibiotic solutions are recommended for routine pin-site care.

- Dressings are not usually necessary once wound drainage has ceased.

- Pin-insertion sites need not be protected for showering or bathing with clean water.

- The patient or the carer should learn and apply the cleaning routine.

Reduction

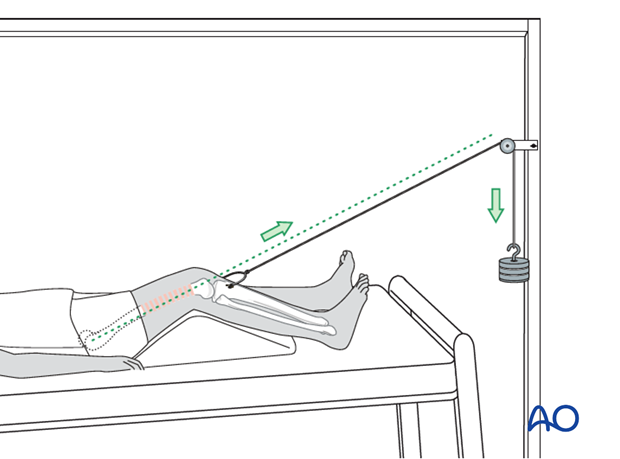

The pull on the femur (weight at the end of the traction) should be enough to correct length and to reduce the fracture.

For maintenance traction 10% of the patient’s body weight is usually enough.

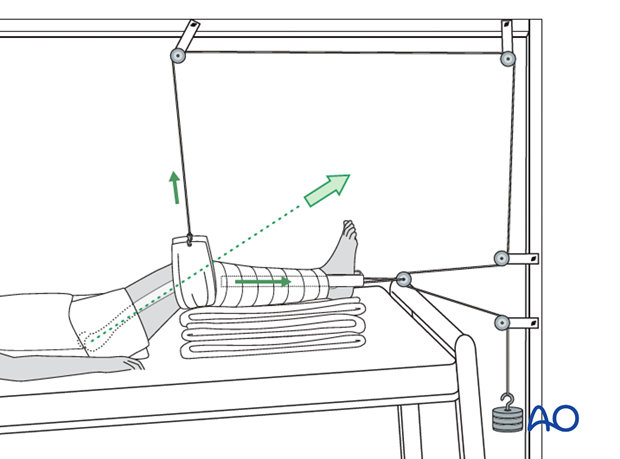

The pull should always be in line with the femur. For that purpose, the height of the pulley on the Balkan beam must be adjustable.

The thigh needs to be supported on a firm triangular foam wedge, or by folded pillows, in order to prevent posterior sag at the fracture site.

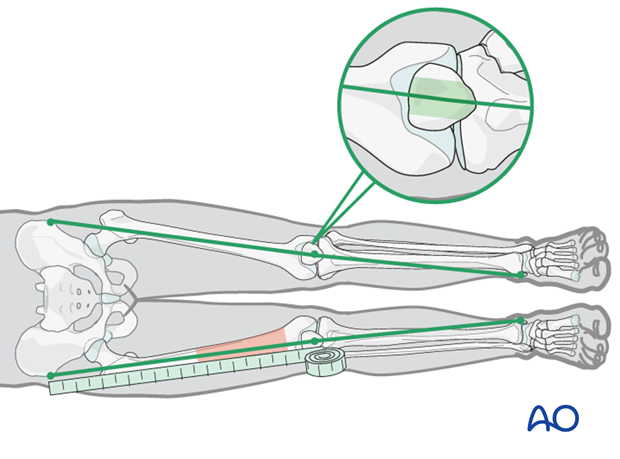

Control of length and rotation

Length and rotation need to be checked daily.

Length is measured by comparison to the uninjured leg. Both legs are brought into comparable positions and the distances from the anterior superior iliac spines, over the knee, to the medial malleoli, are measured and compared.

Adjustment, if required, is done by increasing, or decreasing, the traction weight. Control x-rays need to be taken weekly, if possible, for at least the first 4 weeks.

If the medial/lateral angulation at the fracture site is anatomical, this line will pass over the central third of the patella.

Rotation and maintenance of dorsiflexion in the ankle can be achieved by applying an adhesive sock to the forefoot with a cord over a pulley on the Balkan beam. This pulley should be adjustable from side to side to control rotation.

Distal femur fractures

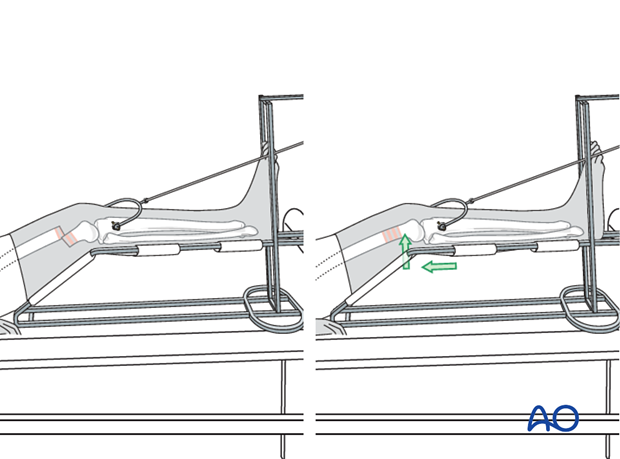

Fractures in the distal third of the femur can be controlled more easily by using a Braun frame.

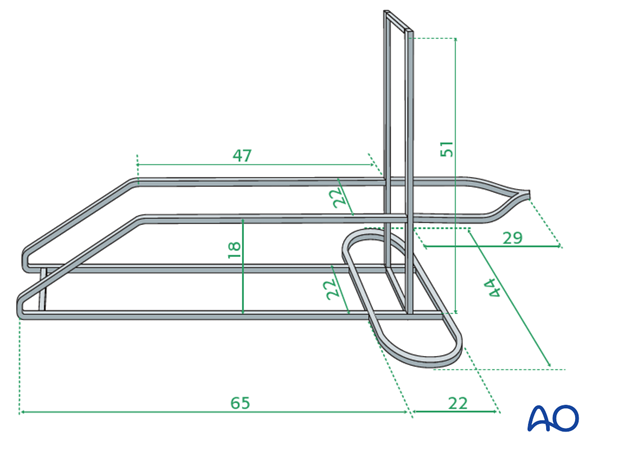

This illustration shows the construction of a Braun-type frame, using metal bars (5 mm x 20 mm).

In order to prevent posterior displacement of the distal fragment, the angle of the padded frame is pushed proximally to support the distal fragment, with appropriate padding.

As soon as the resolution of the pain allows, exercises should be started.

Control x-rays for fracture position need to be taken weekly, if possible, for the first 4 weeks. Thereafter X-rays are only necessary at 4-week intervals to monitor bone healing.

5. Mobilization

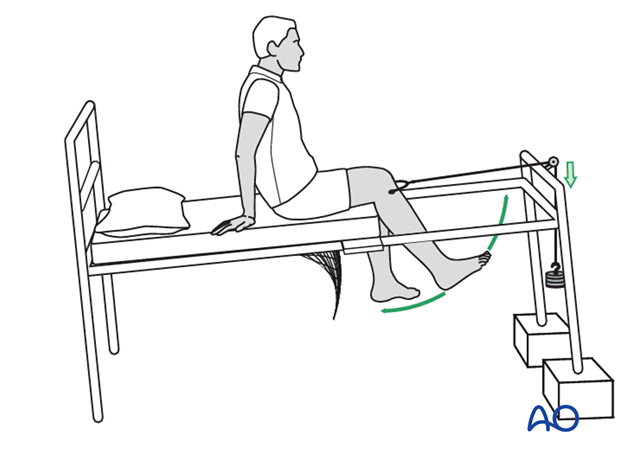

Modification of the bed, as illustrated, will allow early mobilization of the knee as soon as resolution of the pain allows.

A split mattress is used so that the lower half of the bed base can be removed.

With the lower half of the bed base removed and the femoral shaft fully supported by the remaining mattress, the patient starts active knee mobilization after the acute phase (7-10 days).

This comprises active extension exercises and active gravity-assisted flexion exercises, under the supervision of a physical therapist.

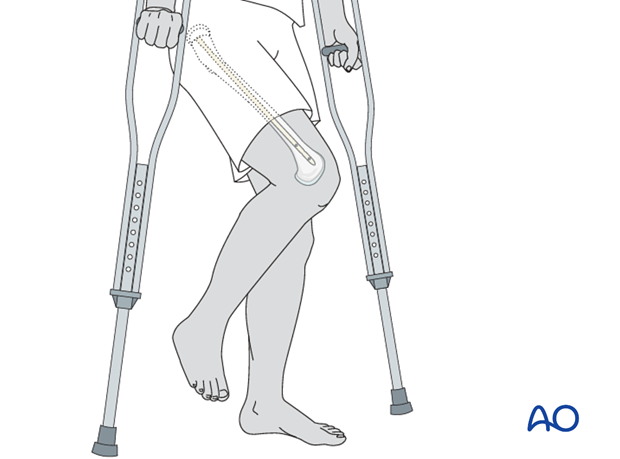

Once the patient can flex the knee from 0 to 90° painlessly and freely, and can actively straight-leg raise with the weights relieved, non-weight bearing mobilization on two crutches can be considered, sometimes as early as 6 weeks after the injury.

From 8 weeks onward, progressive partial weight-bearing should be started and increased to full weight-bearing at +/- 12 weeks.

6. Aftercare

Skeletal traction is usually a temporary device for stabilization of the polytraumatized patient, if a spanning external fixator is for some reason not possible. In general, it would be left on for several days, up to 2 weeks. After this time, definitive surgical stabilization of the distal femoral fracture would be performed.

If the patient is treated definitively with skeletal traction, then a complete nursing care program should be provided that will deal with nutrition, mobilization, physiotherapy, DVT prophylaxis and skin ulcer prevention.

The traction pin sites require regular dressing. If pin site infection occurs this will need to be treated with pin removal, replacement with another pin and appropriate antibiotics and topical antiseptic application.

Inherent in this temporary stabilization are the problems of immobility, pain control, bed sores and heel ulcers. These issues must be carefully addressed during the period of skeletal traction.

Thrombo-prophylaxis should be given according to local treatment guidelines.