ORIF through ilioinguinal approach

1. General considerations

Sequence of the treatment

For ORIF of anterior column/posterior hemitransverse fractures with ilioinguinal approach, the following surgical sequence is common:

- Joint distraction and removal of incarcerated fragments

- Reduction of femoral head dislocation if not achieved closed on admission

- Reduction of marginal impaction

- Reduction and fixation of the anterior fragment(s)

- Reduction and fixation of the posterior column

Planning/templating

Preoperative templating is essential for understanding the complexity of an acetabular fracture.

When using implants on the innominate bone, it is important to know the best starting points for obtaining optimal screw anchorage (see General stabilization principles and screw directions).

Patient positioning

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

2. Principles of reduction

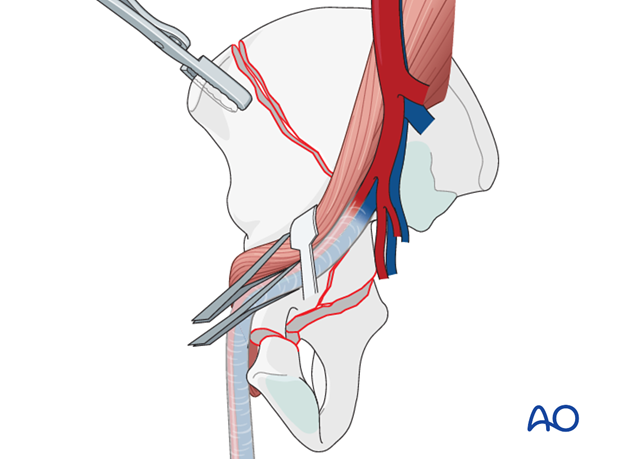

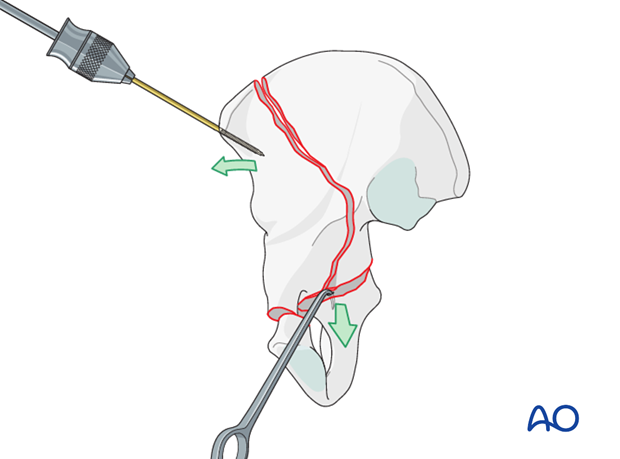

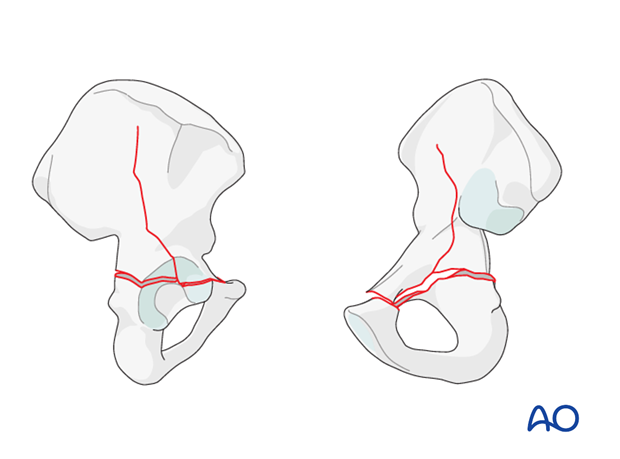

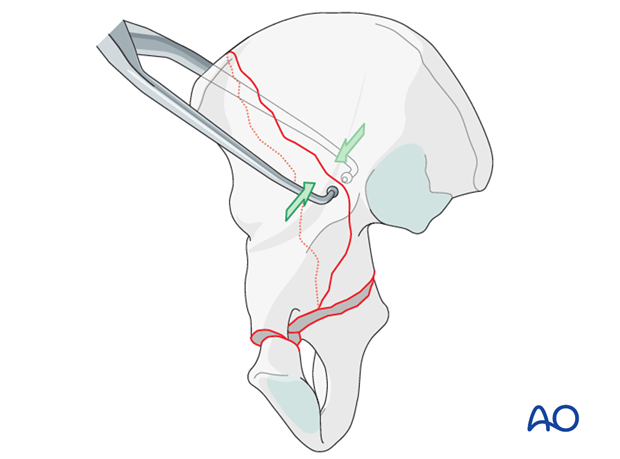

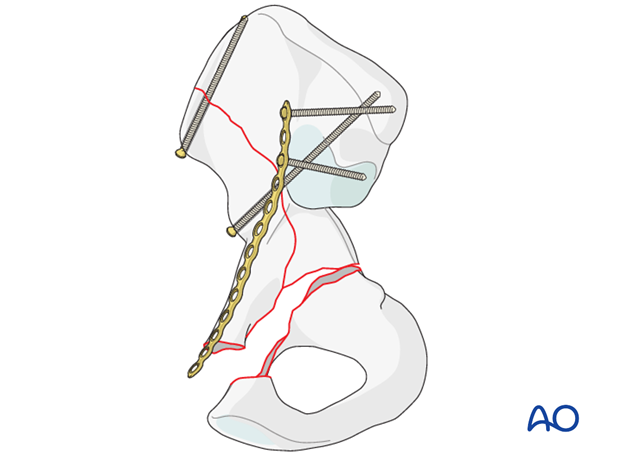

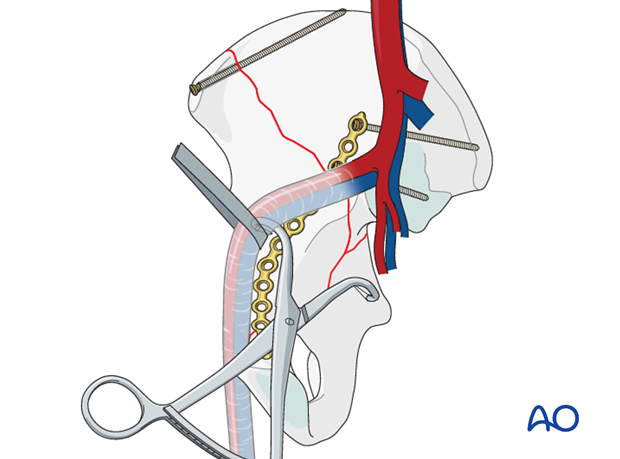

Protection of vessels

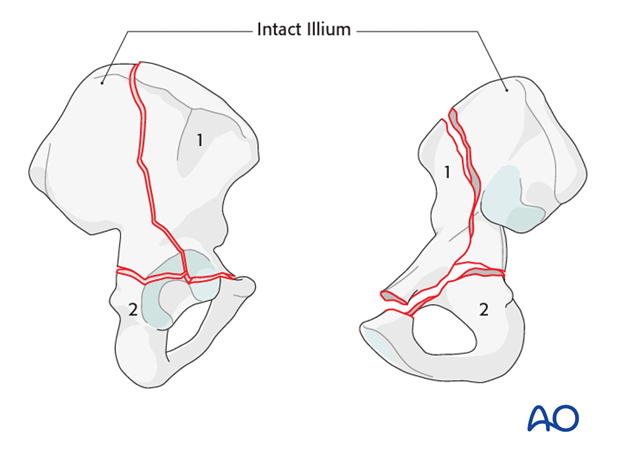

The fracture of the anterior portion is in close proximity to the external iliac artery and vein in the mid column region. The hemitransverse affects the posterior border of the bone near the superior gluteal vascular pedicle. As demonstrated in this illustration, fracture manipulation of both the anterior and posterior fragments threatens injury to these structures.

Great care must be taken throughout the operation to work around these structures, avoid undue tension to these structures, and prevent perforation of any vessels with sharp objects or fracture edges.

Fracture specific reduction and fixation

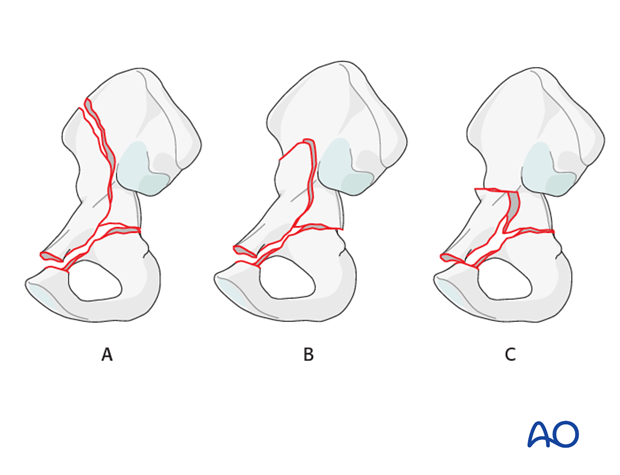

The dissection and fixation strategy is dependent on the height of the fracture.

High anterior column fractures (A) involve a large fragment of extraarticular iliac wing which is often easily manipulated via the lateral window of the ilioinguinal approach. These fractures have significant extraarticular ilium available for plate and screw fixation, such that distal exposure and fixation (ramus) may not be necessary.

Low fractures (C) include very little extraarticular bone. Reduction is difficult due to the small size of the fragment. Obtaining absolute stability is challenging due to the lack of bone stock associated with the small fragment. Interfragmentary screws risk articular penetration and torsional stability requires spanning fixation, both proximally and distally.

Open fracture reduction, from peripheral to central

The anterior fragment(s) (1) are reduced, starting with the proximal end of the fracture, and proceeding distally to the acetabular fossa. The peripheral reduction must be anatomical, since displacement there will aggravate malreduction at the acetabular fossa. However, this is surprisingly difficult to achieve and even very small amounts of malreduction at the iliac crest can prevent accurate reduction of the all-important joint.

Indirect visualization

Unusually for a significant joint, articular reduction of acetabular fractures is indirect. The articular surface of the hip joint is not seen directly. Reduction must be assessed by the appearance of the extraarticular fracture lines and intraoperative fluoroscopic assessment. Some fracture lines are palpated manually but not seen directly such as transverse fracture lines on the quadrilateral plate.

Quality of reduction

Posttraumatic arthrosis is directly related to the quality of reduction - the better the reduction, the greater the chance of a good or excellent result.

3. Joint distraction

Application of traction

It is important to ensure hip flexion to allow enhanced exposure of the iliac fossa and true pelvis.

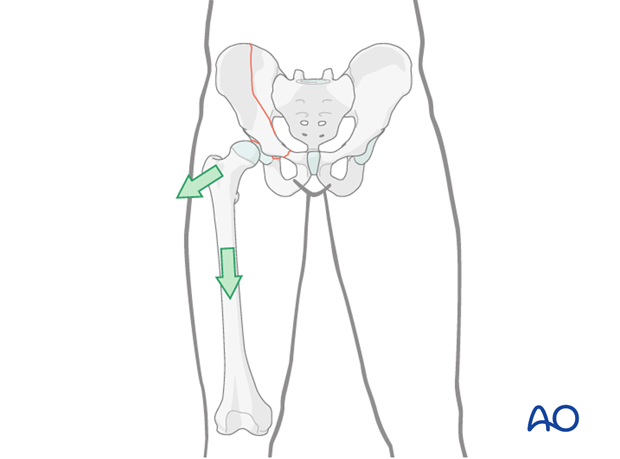

The anterior fragment is a result of displacement or dislocation of the femoral head at the time of injury. In order to allow manipulation of the anterior fragment, the femoral head must be distracted. This is typically accomplished with the application of lateral and/or distal traction.

In some surgeon’s experience, the use of a traction table post or other traction frame is helpful during this operation.

Center the femoral head under the radiological roof using a combination of lateral traction, distal/longitudinal traction, and limb positioning.

Verify the femoral head reduction with the image intensifier.

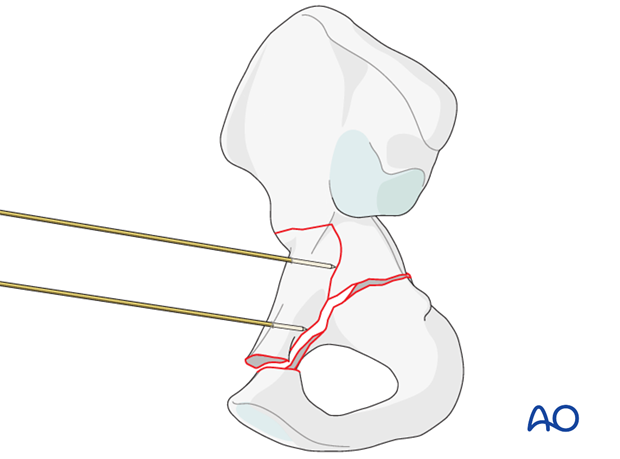

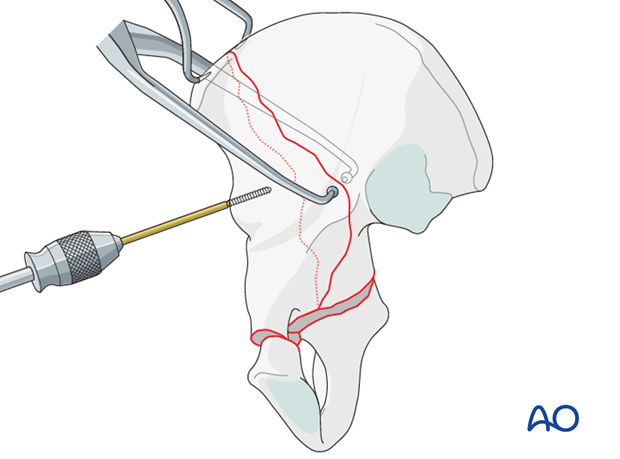

Lateral traction with a trochanter screw

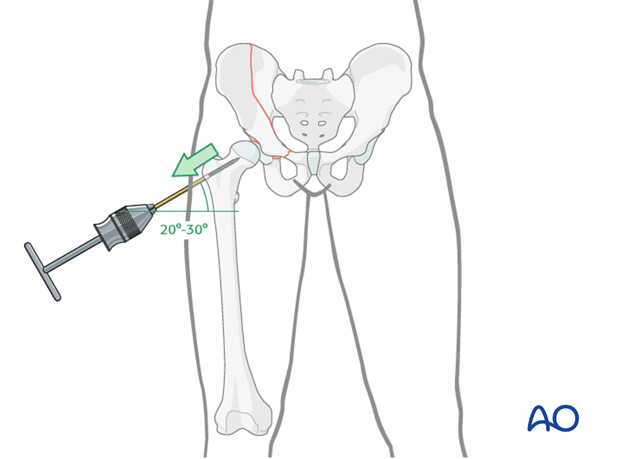

Traction may be applied through a Schanz screw in the greater trochanter, manually or attached to a fracture table.

Insert the screw along the axis of the femoral neck, through a short, separate incision over the greater trochanter.

Distal/longitudinal traction

Distal or longitudinal traction may be applied in the axis of the femur. This can be accomplished manually via a distal femoral traction pin or via a fracture table.

Alternatively, a large distractor may be applied using the following technique.

Insert the proximal 5 mm Schanz screw in the sciatic buttress placed from anterior to posterior. This screw must be cranial to the fracture and into an intact segment of the innominate bone. Based on the fracture through the ilium, this screw may not be possible in high anterior column fractures.

Place the distal Schanz screw into the femur at the level of the lesser trochanter from anterior to posterior. Attach the distractor as shown to these two screws.

Teaching video

AO teaching video: Use of the distractor on the pelvis

4. Cleaning of the fracture site

After exposure of the ilioinguinal, all fracture lines are identified. A periosteal elevator is used to remove periosteum, early callus and granulation tissue.

The fracture sites are cleaned and irrigated in preparation of the direct reduction.

The anterior column may need to be distracted to allow sufficient exposure of the hemitransverse. This may be done with the application of Schanz screws or clamps to manipulate the anterior column fracture.

The displaced posterior fragment is more difficult to manipulate. Once the anterior column has been displaced, a pointed hook can be used to open up the hemitransverse. Alternatively, traction maneuvers on the femoral head may allow sufficient mobilization to access the hemitransverse fracture.

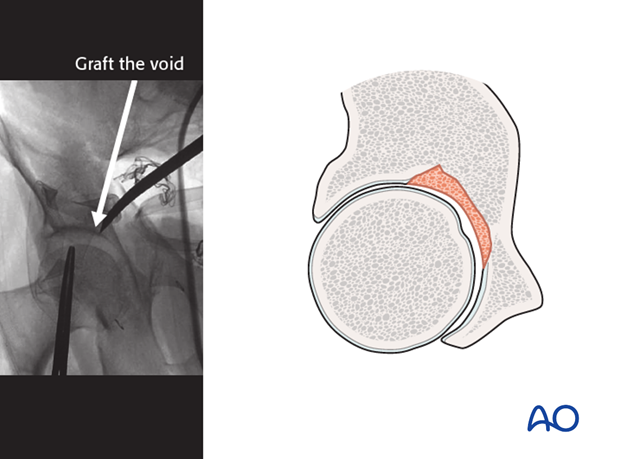

5. Reduction of marginal impaction

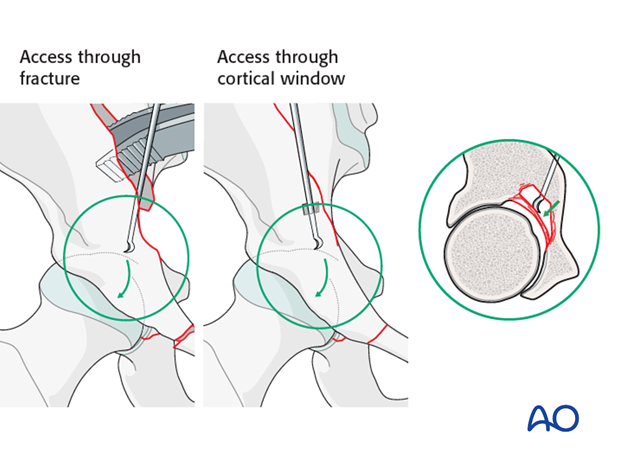

Marginal impaction of the acetabular roof articular cartilage is commonly associated with anterior column and posterior hemitransverse fractures in elderly patients. This marginal impaction must be anatomically reduced and stabilized.

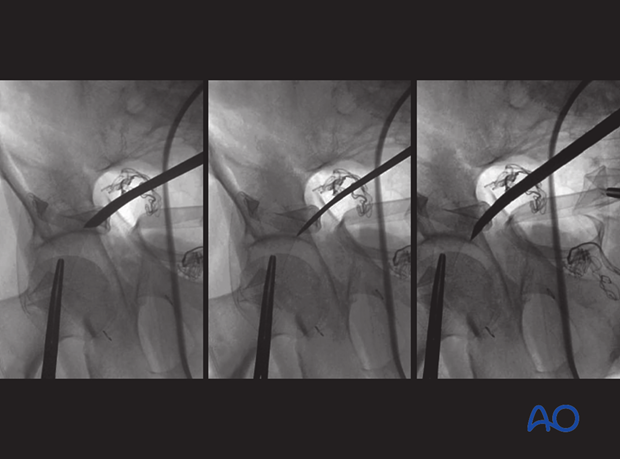

Unlike fractures of the posterior wall, these areas of impaction cannot be directly visualized. Instead, the reduction of these regions requires fluoroscopic guidance.

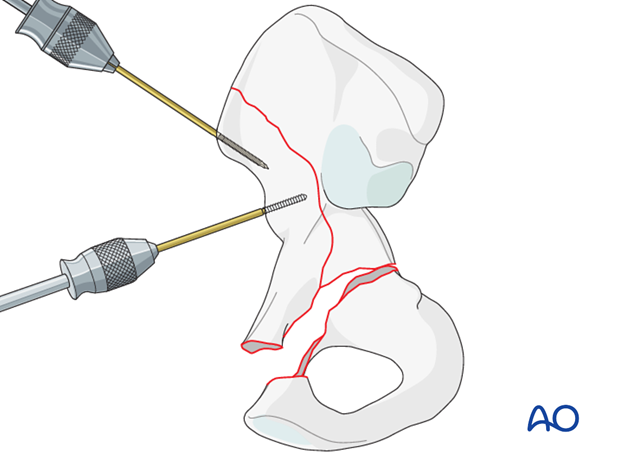

Reduction of this impaction is performed by working through the fracture, or alternatively, through a cortical window created in the ilium.

In either case, the fluoroscopy guides the manipulation and definitive reduction of the impacted segment.

In this example, the osteotome is placed through the fracture.

The area of impaction is mobilized and contoured utilizing the femoral head as a template.

Once the reduced articular surface is in its original position, the defect is filled with cancellous autograft or a bone substitute.

After articular impaction has been addressed, one can proceed with fracture reduction.

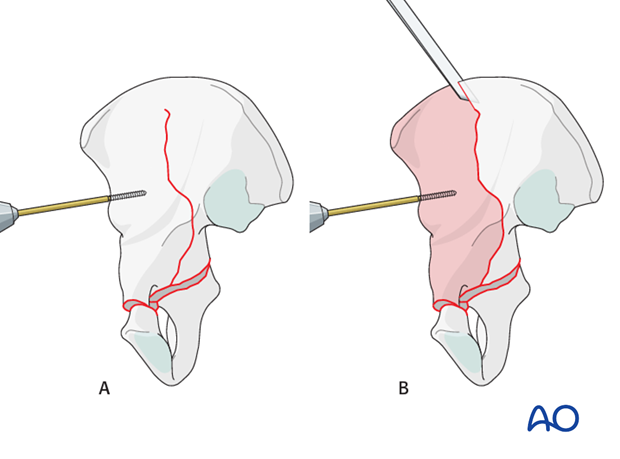

6. Anterior fragment: reduction

Principles

Reduction always starts with the anterior column or wall first. Like anterior column fractures, this reduction is simplified in high and intermediate fracture patterns in which there is sufficient iliac bone associated with the articular fragment to allow manipulation and fixation (A).

This becomes significantly more difficult in the low fractures and the anterior column and posterior hemitransverse in which the anterior fragment is an anterior wall fragment (B). In these cases, utilizing unicortical joysticks, hooks and the ball spike pusher may be the primary adjuncts.

In both cases, the reduction strategies utilized for reduction of the anterior fragments are similar to those described in the corresponding elementary anterior fracture sections of the Surgical Reference.

Osteotomy of incomplete fractures

In some cases, the anterior column fracture is incomplete at the crest and must be osteotomized in order to allow anterior column mobilization and facilitate the reduction.

A Schanz screw is placed in the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) for manipulation which will be possible after the fracture line has been completed with an osteotomy to the iliac crest.

An osteotomy is then created to complete the fracture.

Low and anterior wall fractures

In patterns where the anterior column fracture exits inferior to the crest, reduction strategies are more limited due to the lack of available ilium and the proximity of the articular surface to the fracture lines.

In these cases, lateral traction through the proximal femur is even more important. The effect of indirect reduction via the capsule and labrum is critical in these cases. Utilization of small joysticks (K-wires), ball spike pusher, and carefully applied clamps is critical.

Often these adjuncts must be unicortical to prevent injury to the underlying articular surface.

Reduction tools

If the anterior column fragment is large enough, it may be possible to use a Schanz screw, or two to manipulate the anterior column fragment.

In high fractures, a Schanz screw can be applied to the iliac crest through the first window, and a second Schanz screw placed into the AIIS. The AIIS screw may require percutaneous placement.

Alternatively, reduction and provisional fixation of the iliac crest can be obtained with pointed reduction forceps across the reduced fracture at the iliac crest.

Provisional intramedullary K-wires may be applied along the iliac crest and the iliac corridor as additional fixation.

A ball spike pusher is very helpful in restoring the concavity of the ilium. While the Farabeuf controls the superficial ilium, a ball spike pusher applied just above the pelvic brim with a lateralizing force allows the fragment to abduct and rotate.

The pelvic brim should be reduced to match the brim of the intact segment.

Commonly with these fractures, the internal fracture line will proceed slightly more posteriorly, while the external fracture line diverges anteriorly. This obliquity can be utilized in clamp application.

When the fracture obliquity permits, a tong clamp can be used which spans from the internal iliac fossa to the external ilium utilizing a limited external iliac exposure.

Reduction with a plate

Plate reduction techniques are extremely useful in this fracture pattern.

The plate is undercontoured to provide both a posterior push and an abduction force on the displaced mid-column region.

A pelvic brim plate is applied initially posteriorly, exerting a reduction force on the anterior column as the screws are tightened.

It is frequently necessary to use several of these reduction techniques in concert to achieve an anatomic reduction.

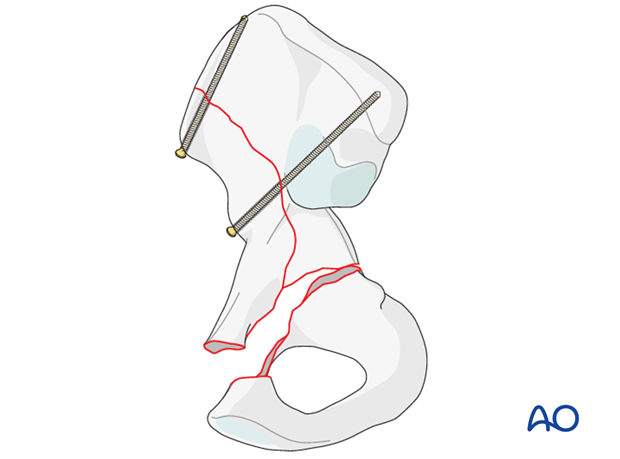

7. Anterior fragment: fixation

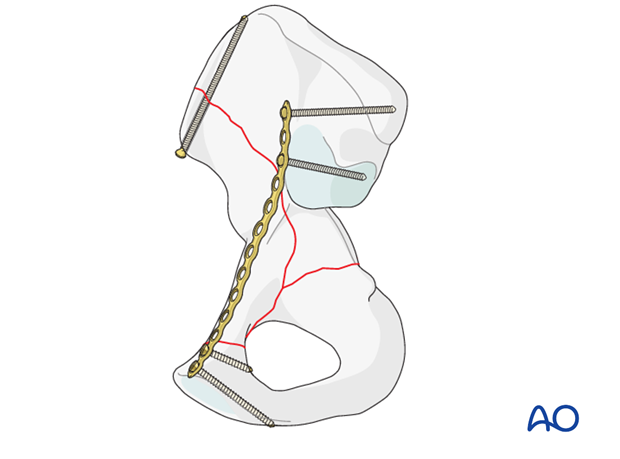

Plate and screw fixation

Stabilization of the anterior column or wall starts peripherally with the crest or ilium, and can be achieved with either screws or reconstruction plates.

Depending on the height of the fracture, screws utilizing the iliac corridor from the AIIS to the posterior sciatic buttress may be useful.

These screws can begin laterally at the AIIS even in low fractures. If the fracture permits, these iliac corridor screws may be placed in the internal fossa lateral to the pelvic brim.

In some cases of high anterior column fractures, with high bone quality, it may be possible to achieve stable fixation with interfragmentary screws alone.

Most commonly, however, screw fixation is augmented with a buttress plate placed along the pelvic brim extending from the area lateral to the SI joint to the superior pubic ramus.

Note that screws have not yet been placed into the mid-section of the plate. Reduction of the posterior fragment is required before screw placement into the posterior column.

8. Posterior column: reduction

Following reduction and provisional or definitive stabilization of the anterior column, the posterior column can then be addressed.

Preliminary correction of the posterior column displacement is achieved with lateral traction in most cases, but it usually must be adjusted to be truly anatomical.

A number of clamps are useful for this purpose, including the pointed reduction (Weber) clamp, the offset jaw clamps, or the large asymmetric pelvic reduction forceps.

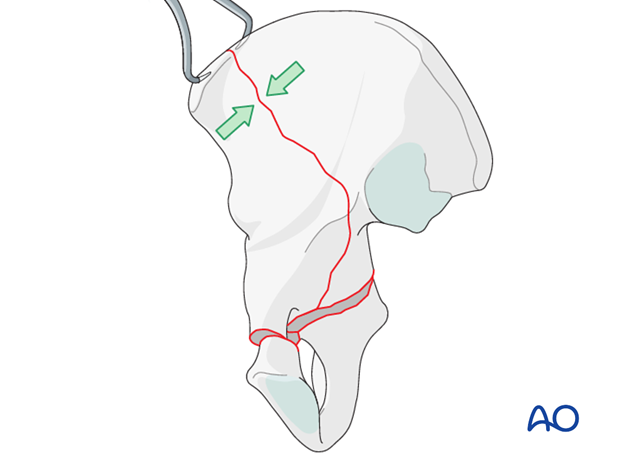

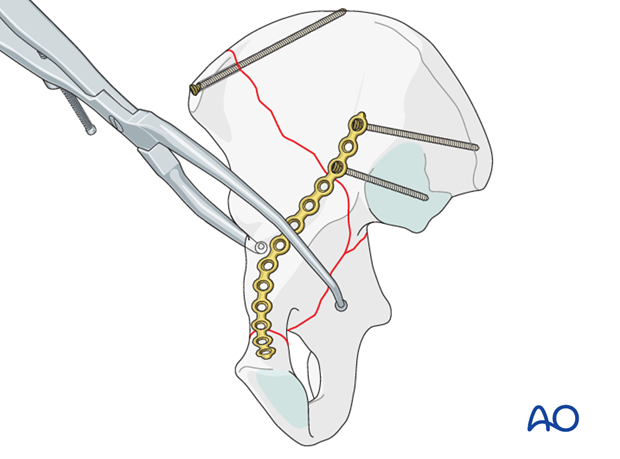

Use of asymmetric reduction forceps

The clamp demonstrated is a large asymmetric pelvic reduction forceps. This clamp straddles the iliac crest from the quadrilateral surface internally to the lateral aspect of the ilium, or the anterolateral surface of the iliopectineal eminence.

The internal point is placed through the first or second window, depending on the access afforded by the exposure. If sufficient hip flexion has been obtained, this clamp may be placed through the first window.

The external point requires a small submuscular dissection along the external surface of the iliac crest.

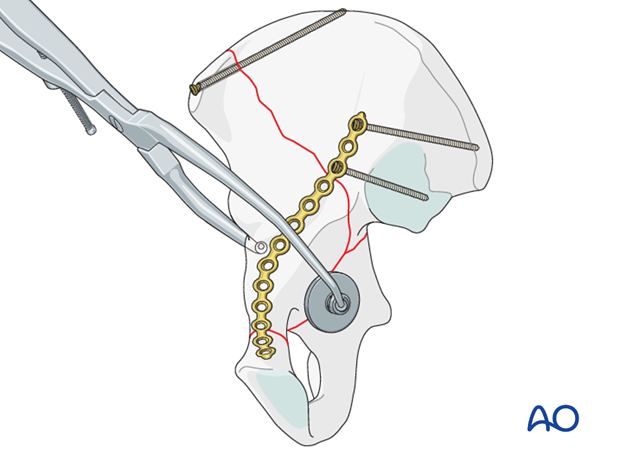

In cases of osteoporosis, or quadrilateral surface comminution, a disc applied to the ball points of these clamps may be used to avoid cortical perforation.

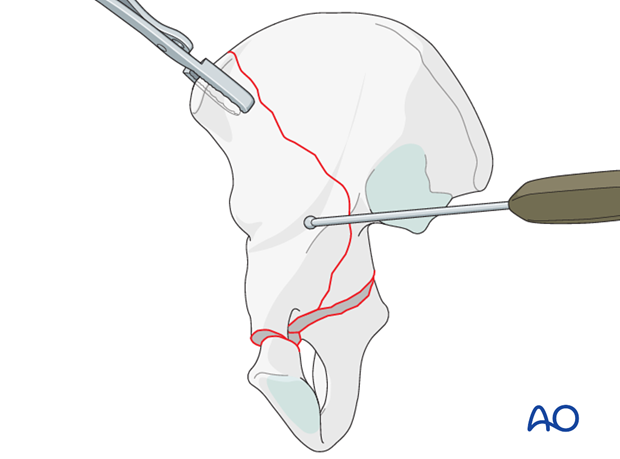

Offset quadrangular clamp

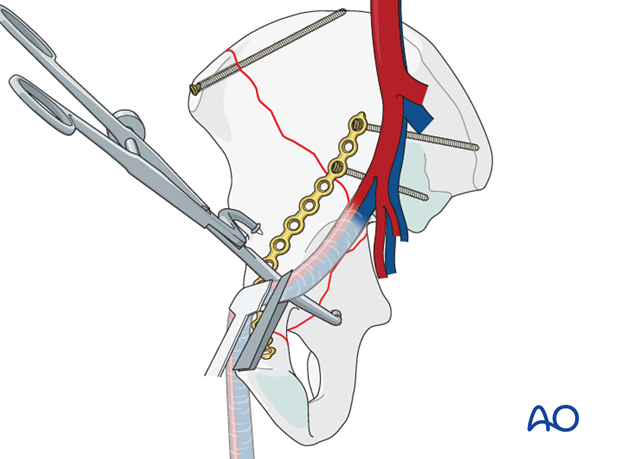

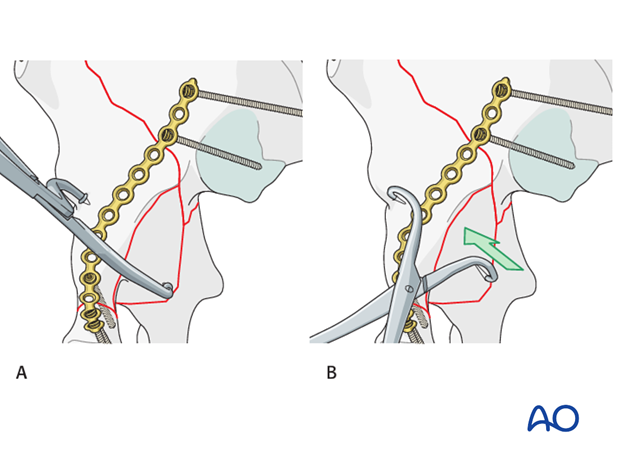

The offset jaw clamp was designed to reduce the posterior column to the anterior column through the second window of the Ilioinguinal approach.

The internal point is placed onto the displaced posterior column or quadrilateral surface. The superficial point is placed onto the anterior surface of the mid anterior column.

This clamp requires medial displacement of the external iliac vessels. Care must be taken to avoid excessive traction on the vascular structures with this clamp application.

Use of pointed reduction forceps

The pointed reduction forceps can be applied through the modified third window (modified Stoppa interval) to reduce the displaced posterior fragment to the anterior column.

In this case, the vessels will be elevated to allow the superficial point to be applied above the pelvic brim.

Completion of the anterior column plate

After reduction, the plate can be secured inferiorly to the pubic ramus and the body of the pubis. Distal fixation becomes increasingly important in lower fractures.

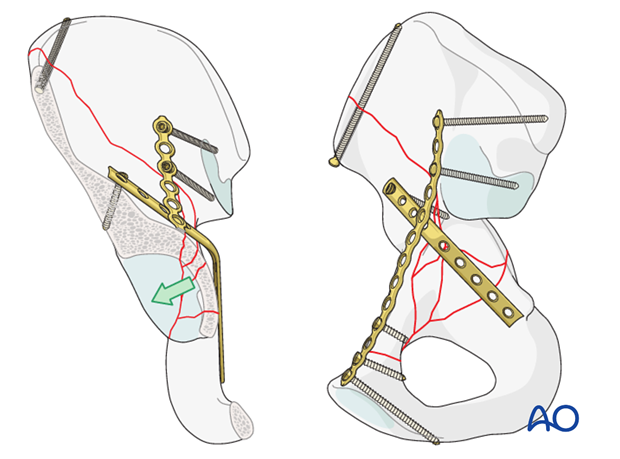

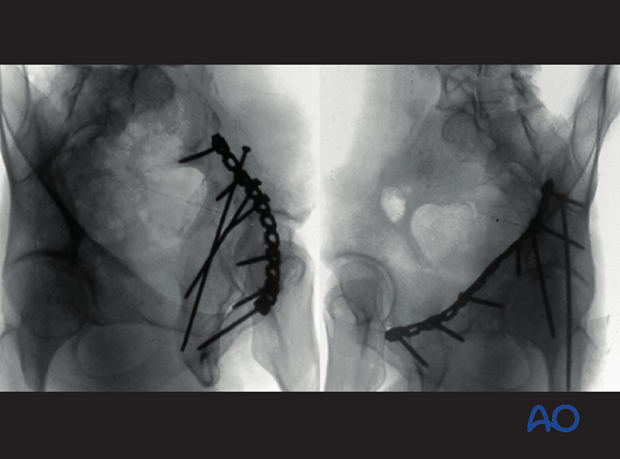

9. Posterior column: fixation

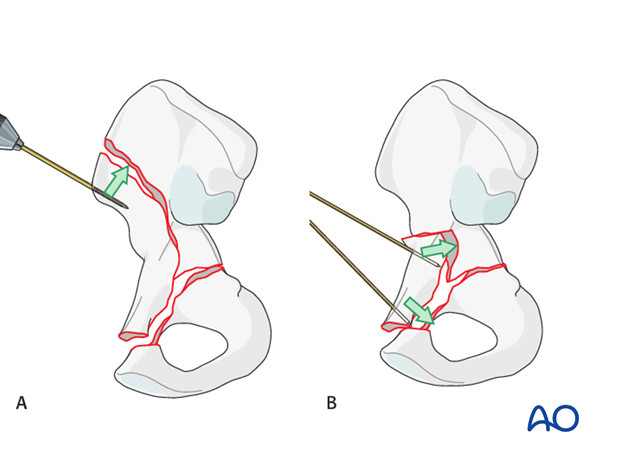

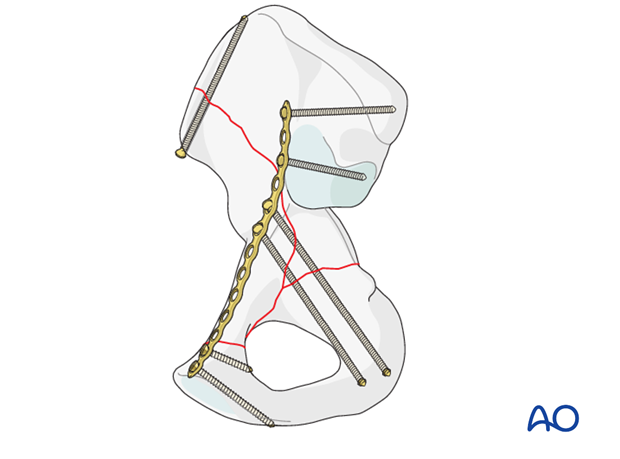

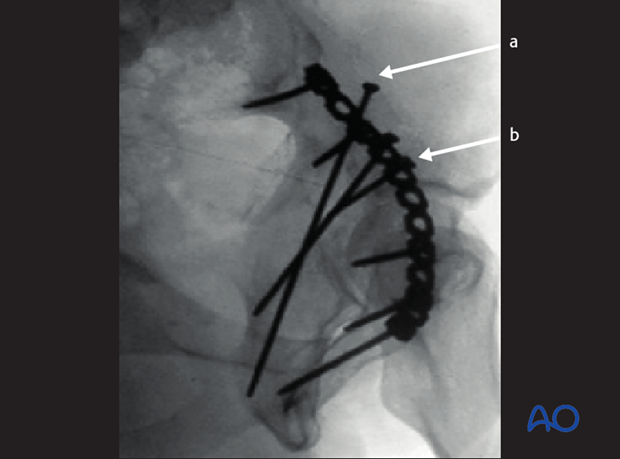

Anterior to posterior screw fixation

Once the posterior column has been reduced anatomically, various methods of fixation can be achieved.

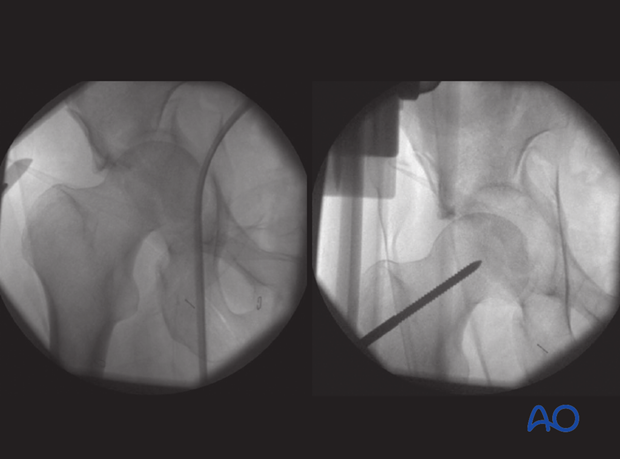

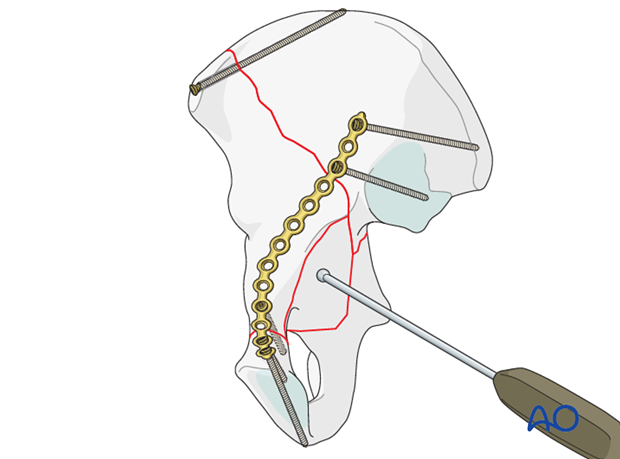

Fixation of the posterior column is commonly provided by anterior to posterior screws inserted from the pelvic brim into the posterior column.

These screws may be applied through the pelvic brim plate or outside of the plate. Use the corridor that extends from the cranial limit of the greater sciatic notch distally to the ischium.

The posterior column screws placed from the ilioinguinal are most commonly applied through the first window. In some cases, the entry point of these screws may be slightly more distal, requiring application through the second window.

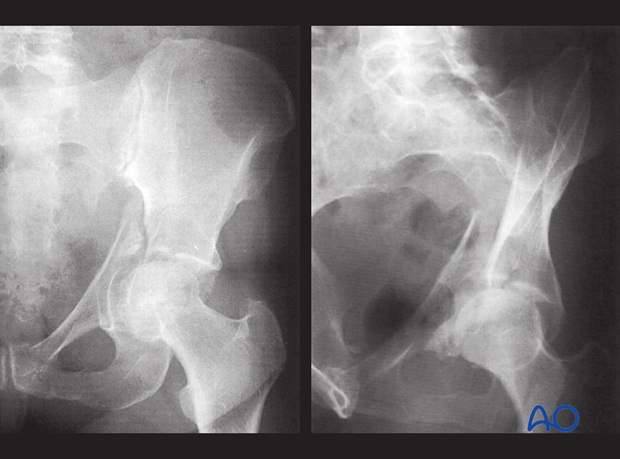

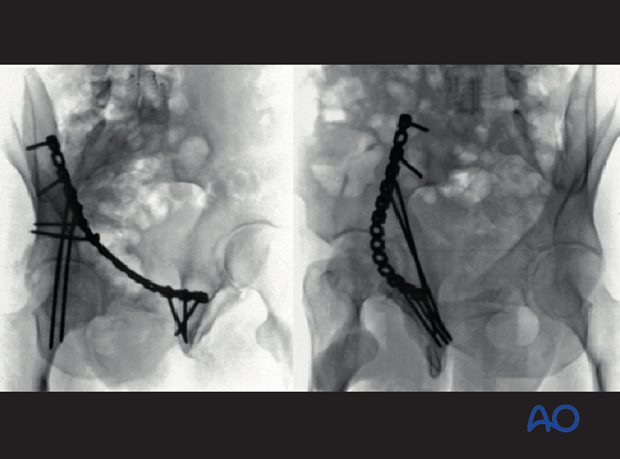

As seen in this x-ray, these screws may be applied independent from the pelvic brim plate (a) or through the plate (b).

This corridor is in close proximity to the acetabulum and intraarticular perforation must be avoided. Utilization of the iliac oblique fluoroscopic image to navigate placement of these screws is recommended.

The iliac oblique will demonstrate the posterior order of the innominate bone, the sciatic notch and the superior posterior acetabular margin. The image can be obtained to demonstrate the entire posterior column corridor.

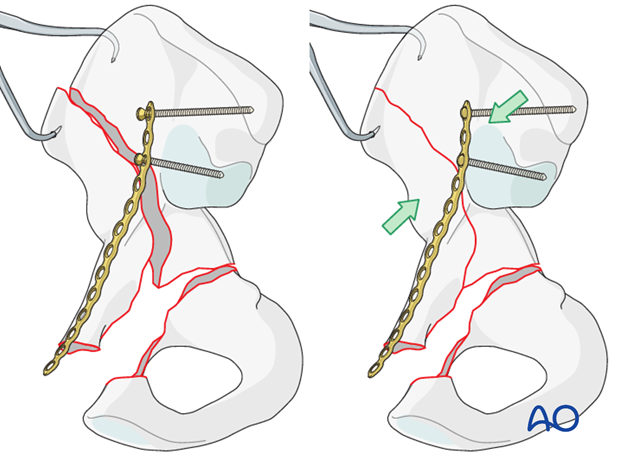

Screw directions

The location of an obliquity of the hemitransverse fracture line relative to the iliopectineal line will affect screw placement and direction. Ideally the screw trajectory is perpendicular to the fracture plane. Therefore, a shorter well-placed screw may be more powerful than a long screw transversing the entire posterior column (A).

In some cases, with fracture obliquity, it is best for the screws to actually perforate the quadrilateral surface, and be inserted percutaneously from the lateral aspect of the ilium (B).

Depending on the location of the fracture, these screws may be relatively short, or in the case of distal fractures, need to be very long.

10. Quadrilateral surface fragment: reduction and stabilization

Reduction

In anterior column/posterior hemitransverse fractures that involve a separate quadrilateral surface fragment, it may be necessary to reduce and stabilize this fragment.

The quadrilateral plate fragment may be reduced with the offset jaw clamp applied through the second window (A), or the pointed reduction forceps applied through the modified third window (B) (as described above for the posterior column reduction).

Care must be taken to avoid further fragmentation of this fragment, as the bone is typically very thin and severely osteoporotic.

Alternatively, the quadrilateral surface fragment may be addressed with a ball spike pusher (or other push device) applied via the modified third window (modified Stoppa interval).

Stabilization with anterior to posterior screws

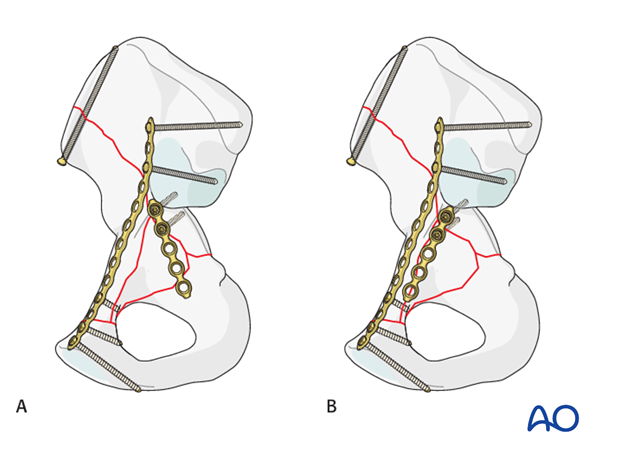

Three strategies have been described for stabilization of the quadrilateral surface and the posterior column.

Anterior to posterior screws can successfully stabilize the quadrilateral surface, if the fragment is sufficiently large and the bone quality good. These screws are placed starting lateral to the pelvic brim and are diverted towards the posterior column corridor as described above. They provide insufficient fixation in osteoporotic bone.

Stabilization with an infrapectineal buttress plate

A plate can be placed on the quadrilateral surface to buttress comminution or counteract posterior column medial displacement.

This plate is placed under direct visualization thought the third window of the ilioinguinal approach.

There are multiple plating options available for the quadrilateral surface. Utilizing 3.5 mm reconstructive or tubular plates undercontoured to provide a buttressing effect; these plates can be oriented either down the posterior column (A), or down the anterior column towards the pubic ramus (B).

This plate is typically fixed into the dense bone in the sciatic buttress just anterior to the SI joint. The obturator oblique radiograph can be useful in ensuring that these screws are extraarticular.

Stabilization with a spring plate

Alternatively, quadrilateral surface comminution can be stabilized with the use of a supplemental spring plate.

This plate is generally applied beneath a spanning pelvic brim plate, over the pelvic brim through the first window to avoid intrapelvic dissection.

11. Final radiographic assessment

Confirm fracture reduction with AP, iliac and obturator oblique fluoroscopic images. The position of all screws should be assessed, particularly those close to the acetabulum.

The obturator oblique will verify that the screws placed through the quadrilateral surface fixation are extraarticular. The iliac oblique will ensure that the posterior column reduction is anatomic, and that the posterior column screws are extraarticular.

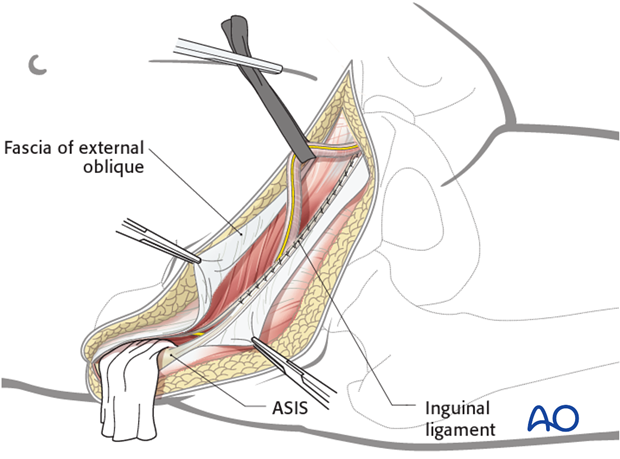

12. Wound closure

Before closure, one may place drains in the space of Retzius and anterior internal iliac fossa.

Layered closure then begins with repair of the conjoint tendon to the distal inguinal ligament. A careful fascial repair restores the floor of the inguinal canal.

The external oblique aponeurosis and the rectus sheath are then repaired, followed by secure reattachment of the abdominal wall origin to the iliac crest, in the lateral portion of the incision. A hernia-free repair, and avoidance of entrapment of the spermatic cord should be achieved.

Subcutaneous drains may be inserted.

Finally, perform an appropriate subcutaneous and skin closure.

13. Postoperative care

During the first 24-48 hours, antibiotics are administered intravenously, according to hospital prophylaxis protocol. In order to avoid heterotopic ossification in high-risk patients, the use of indomethacin or single low dose radiation should be considered. Every patient needs DVT treatment. There is no universal protocol, but 6 weeks of anticoagulation is a common strategy.

Wound drains are rarely used. Local protocols should be followed if used, aiming to remove the drain as soon as possible and balancing output with infection risk.

Specialized therapy input is essential.

Follow up

X-rays are taken for immediate postoperative control, and at 8 weeks prior to full weight bearing.

Postoperative CT scans are used routinely in some units, and only obtained if there are concerns regarding the quality of reduction or intraarticular hardware in others.

With satisfactory healing, sutures are removed around 10-14 days after surgery.

Mobilization

Early mobilization should be stressed and patients encouraged to sit up within the first 24-48 hours following surgery.

Mobilization touch weight bearing for 8 weeks is advised.

Weight bearing

The patient should remain on crutches touch weight bearing (up to 20 kg) for 8 weeks. This is preferable to complete non-weight bearing because forces across the hip joint are higher when the leg is held off the floor. Weight bearing can be progressively increased to full weight after 8 weeks.

With osteoporotic bone or comminuted fractures, delay until 12 weeks may be considered.

Implant removal

Generally, implants are left in situ indefinitely. For acute infections with stable fixation, implants should usually be retained until the fracture is healed. Typically, by then a treated acute infection has become quiescent. Should it recur, hardware removal may help prevent further recurrences. Remember that a recurrent infection may involve the hip joint, which must be assessed in such patients with arthrocentesis. For patients with a history of wound infection who become candidates for total hip replacement, a two-stage reconstruction may be appropriate.

Sciatic nerve palsy

Posterior hip dislocation associated with posterior wall, posterior column, transverse, and T-shaped fractures can be associated with sciatic nerve palsy. At the time of surgical exploration, it is very rare to find a completely disrupted nerve and there are no treatment options beyond fracture reduction, hip stabilization and hemostasis. Neurologic recovery may take up to 2 years. Peroneal division involvement is more common than tibial. Sensory recovery precedes motor recovery and it is not unusual to see clinical improvement in the setting of grossly abnormal electrodiagnostic findings.