Open reduction - Screw fixation

1. General considerations

Introduction

Displaced avulsion fractures of the tibial spine require internal fixation to restore the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

This can be achieved with arthrotomy and screw fixation.

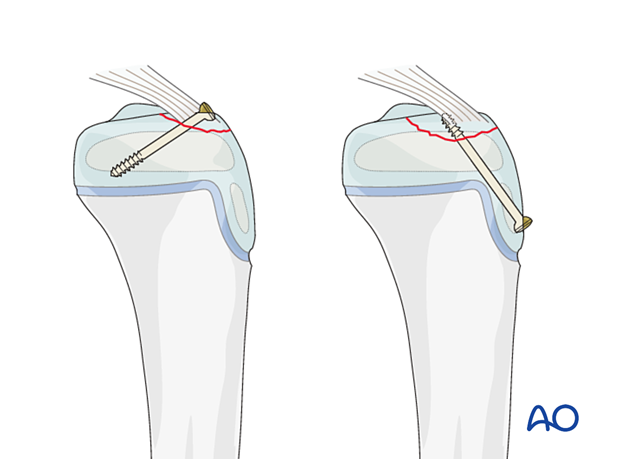

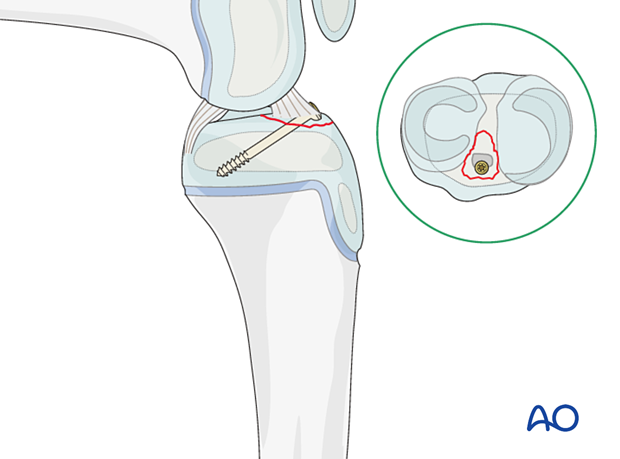

Antegrade screw fixation

A large tibial spine fragment may be stabilized using a screw.

The screw should not cross the physis.

Depending on the size of the fragment, one or two antegrade screws may be used.

Small or comminuted fragments should be stabilized with a suture.

Crossing the physis should be avoided but this may result in decreased stability.

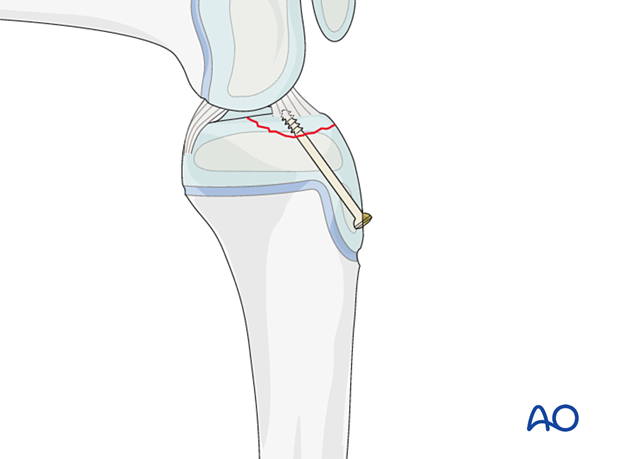

Retrograde screw fixation

The screw(s) may be inserted along the line of action of the ACL and this has the advantage of easier implant removal.

The thread of a retrograde partially cannulated screw may limit compression across the fracture and the correct ACL tension may, therefore, not be restored.

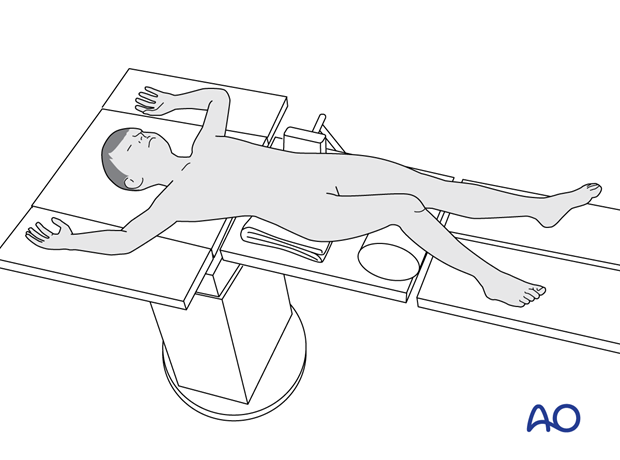

2. Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

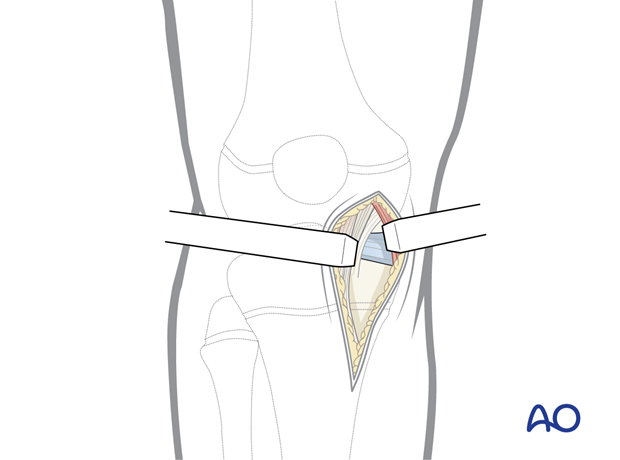

3. Approach

For open reduction, a medial parapatellar arthrotomy is used. The incision is enlarged as necessary for reduction and screw insertion.

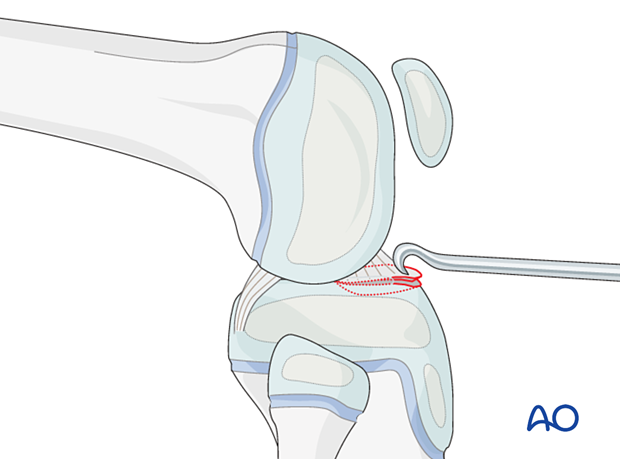

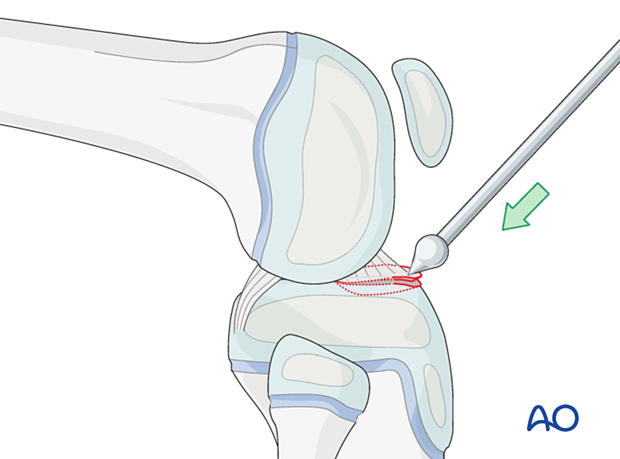

4. Reduction

Reduce the spine fragment with a hook …

… or a ball spike pusher.

Confirm the reduction under direct vision or with an image intensifier.

5. Fixation

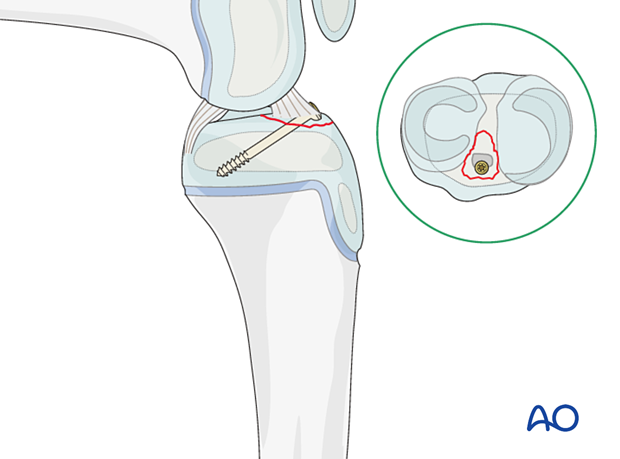

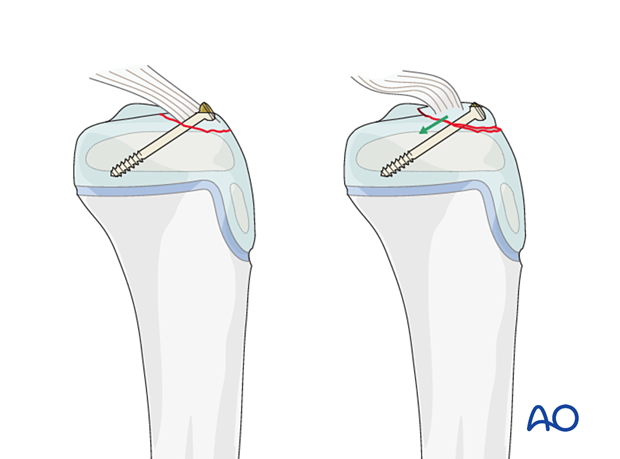

Antegrade lag-screw fixation

Flex the knee to 80°.

Insert a screw ensuring that it does not cross the physis, or compromise the articular cartilage or ligament insertion sites.

Cannulated small fragment screws are the implant of choice.

To avoid dorsal displacement, maintain the fracture reduction with a hook during screw insertion.

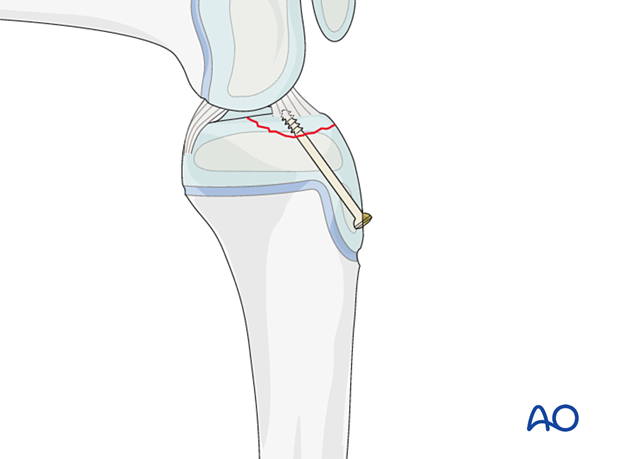

Alternative: retrograde lag screw fixation

Fixation of a solid avulsion fragment can be performed with a small cancellous screw.

The entry point should be proximal to avoid injury to the physis.

6. Final assessment

Confirm reduction of the fragment with arthroscopy and an image intensifier and tension of the ACL with clinical examination.

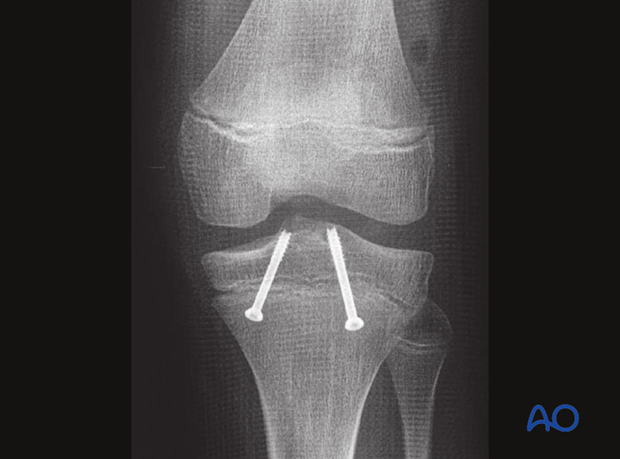

This lateral view x-ray shows the case of a tibial spine avulsion stabilized with two retrograde lag screws.

AP view x-ray of the same case

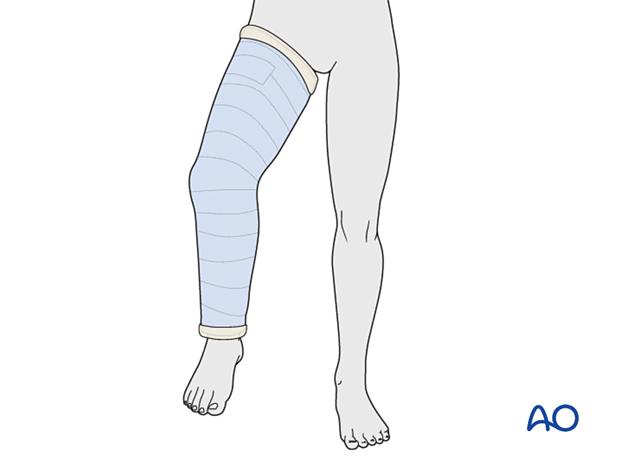

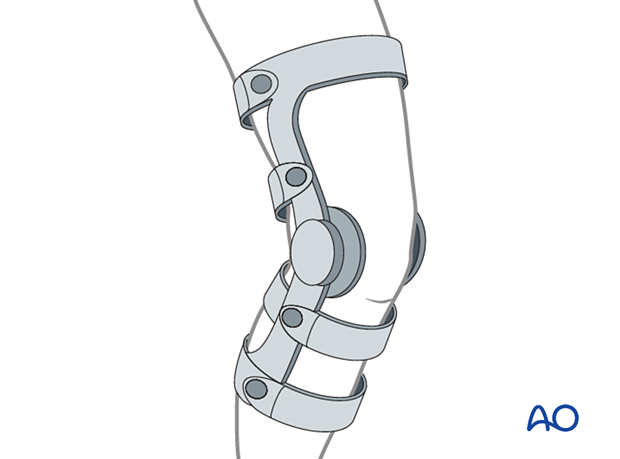

7. Immobilization

Depending on the stability of fixation, a cylinder cast with the knee flexed to 20°–30° may be applied for 4–6 weeks.

Alternatively, a hinged knee brace may be used with a gradually increasing range of motion over 6 weeks, with the patient instructed to remain touch-weight bearing.

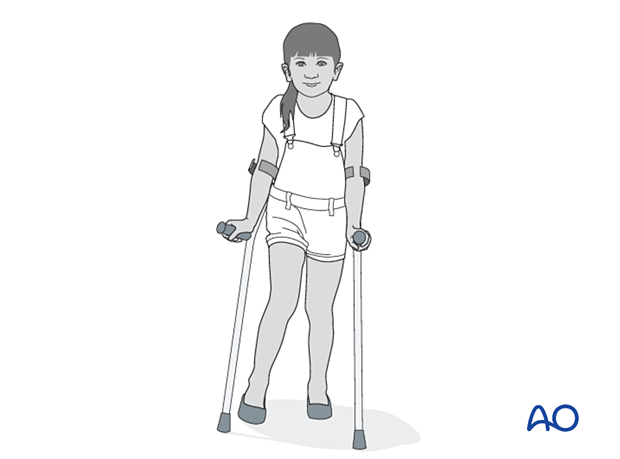

8. Aftercare

Immediate postoperative care

The patient is kept touch-weight bearing.

Older children may be able to use crutches or a walker.

Younger children may require a period of mobilization in a wheelchair.

Neurovascular examination

The patient should be examined frequently in the initial period following the injury, to exclude neurovascular compromise or evolving compartment syndrome.

High-energy fractures are associated with vascular injuries and require careful clinical assessment.

Follow-up

The first clinical and radiological follow-up is usually undertaken at 6 weeks.

Long-term follow up with clinical assessment of ligament stability is mandatory because of possible residual ACL insufficiency.

Growth disturbance is rare as the fracture usually does not involve the physis. Growth arrest of the tibial apophysis may result in recurvation malalignment. This should also be checked in a long-term follow-up (ca 2 years after trauma).

Implant removal

Implants are usually removed after 3–6 months.