Compartment syndrome (lower limb)

1. Introduction

Definition

Muscles are arranged in groups, enveloped by fascia, which is particularly thick below the elbow and knee.

These groups are referred to as compartments and the fascia is inelastic and limits an increase in volume.

Bleeding and the associated soft tissue injury at a fracture site will therefore cause an increase in pressure within the compartment.

This causes ischemia of nerve and muscle tissue and leads to pain, altered sensation, paresthesia, and weakness or paralysis of the distal part of the limb.

This constellation of symptoms is referred to as compartment syndrome.

Suspected compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency.

Principles

Compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure within a closed myofascial compartment rises above a critical level.

This occurs following fracture, particularly after high-energy trauma with significant soft-tissue injury and can also occur in open fractures.

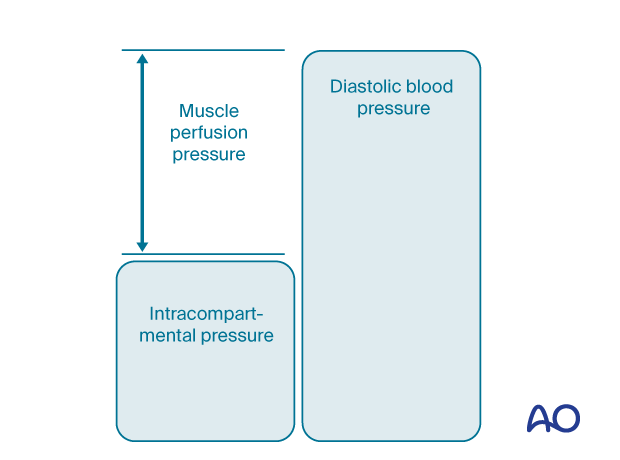

The capillary filling pressure is close to the diastolic arterial pressure and if the intramuscular tissue pressure approximates the diastolic pressure, capillary blood flow ceases leading to progressive ischemia and tissue death.

The critical factors are the rate of, and relative increase in, the intramuscular tissue pressure leading to extrinsic compression, which reduces capillary bed perfusion.

A number of studies have demonstrated that if the difference between diastolic arterial pressure and intracompartmental pressure is <30 mm Hg, capillary blood flow is significantly reduced and rapidly causes nerve and muscle ischemia.

See also:

- Gourgiotis S, Villias C, Germanos S, et al. Acute limb compartment syndrome: a review. J Surg Educ. 2007 May–Jun;64(3):178–186.

- Mabee JR. Compartment syndrome: a complication of acute extremity trauma. J Emerg Med. 1994 Sep–Oct;12(5):651–656.

The muscle perfusion pressure (MPP) is the difference between diastolic blood pressure (dBP) and intracompartmental pressure.

MPP reflects altered tissue perfusion more reliably than the absolute intramuscular pressure measured in isolation.

Low diastolic blood pressure in a shocked patient, in association with an increased local intracompartmental pressure, greatly reduces the MPP.

The longer the duration of hypoxia, the greater the likelihood of irreversible tissue damage.

Unmyelinated nerves are more sensitive to ischemia than myelinated nerves and sensory symptoms therefore develop before muscle weakness.

An arterial injury proximal to the compartment may lead to intracompartmental ischemia. When arterial flow is restored, capillary leakage increases the intracompartmental pressure.

This may contribute to muscle ischemia and is referred to as reperfusion injury.

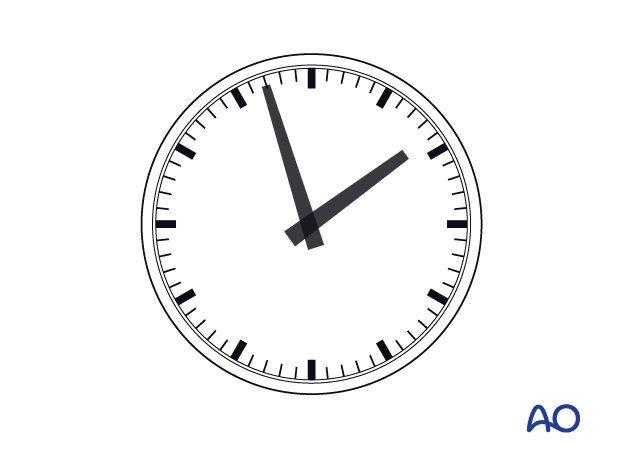

Timing

It is of paramount importance that fasciotomy is performed as soon as the diagnosis is made.

Fasciotomy later than 24 hours will expose necrotic tissue with a high risk of infection and will not improve long term limb function.

2. Compartmental anatomy of the lower leg

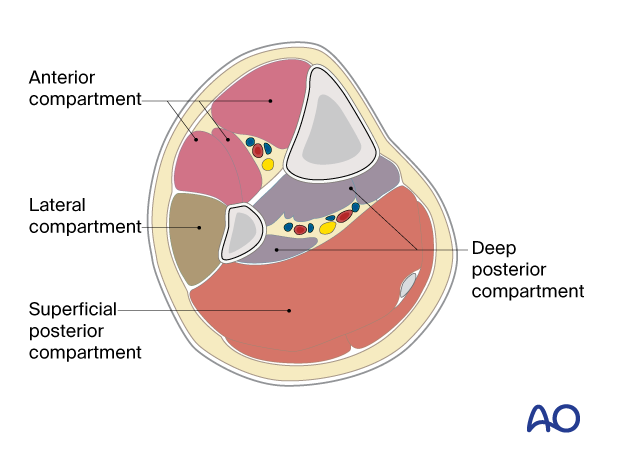

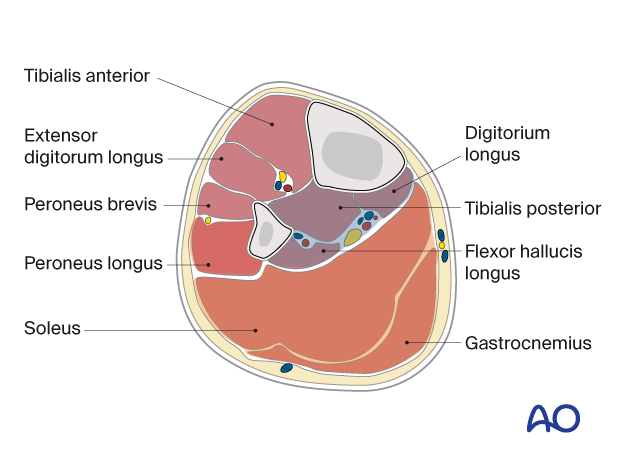

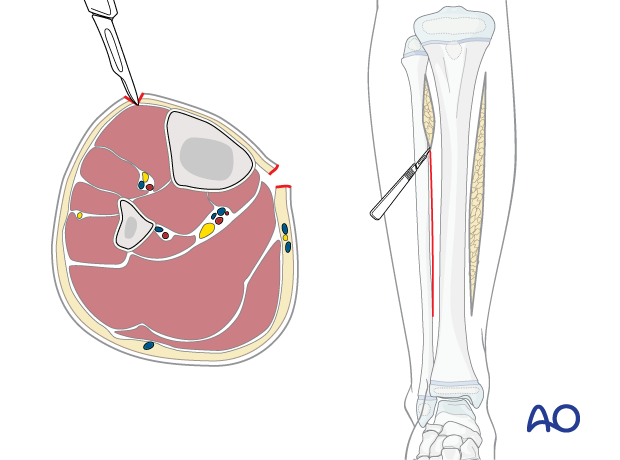

The lower leg has four compartments.

The anterior compartment contains:

- Tibialis anterior

- Extensor hallucis longus

- Extensor digitorum longus

- Anterior tibial artery

- Deep peroneal nerve

The lateral compartment contains:

- Peroneus longus

- Peroneus brevis

- Superficial peroneal nerve

The deep posterior compartment contains:

- Tibialis posterior

- Flexor hallucis longus

- Flexor digitorum longus

- Peroneal artery

- Posterior tibial artery

- Tibial nerve

The superficial posterior compartment contains:

- Gastrocnemius

- Soleus

- Sural nerve

Relevant anatomy - Muscles

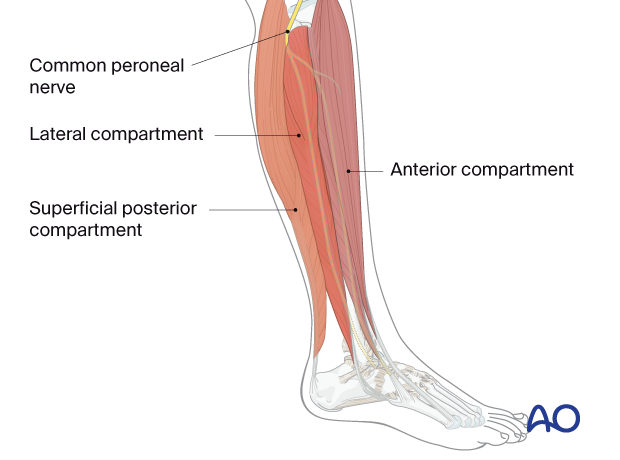

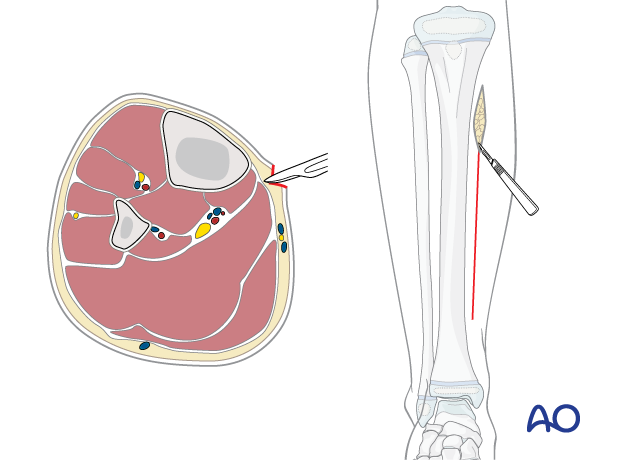

The anterior and lateral muscle compartments are approached via an anterolateral incision.

The superficial and deep posterior compartments are approached through a separate medial incision.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the four compartments and the muscles within them is essential for safe decompression.

It is important to protect the common peroneal nerve, as it crosses the proximal fibula, in addition to subcutaneous nerves throughout the length of the surgical incisions.

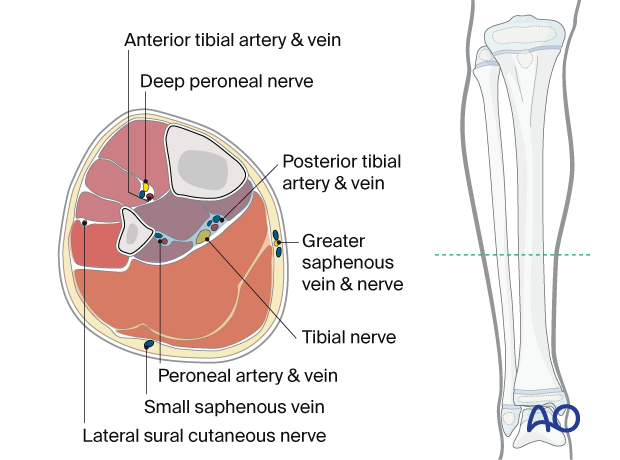

Relevant anatomy - Neurovascular structures

The structures at risk are the following.

Medial incision:

- Saphenous nerve

- Long saphenous vein

Lateral incision:

- Superficial peroneal nerve

Deep dissection:

- Posterior tibial nerve

- Posterior tibial artery

3. Diagnosis

Symptoms

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome should be suspected in a conscious and alert patient, when the following early signs are present:

- Pain, unrelated to the posture of the limb, made worse by passive movement of muscles in the relevant compartment

- Paresthesia

- Progressive loss of light touch sensation

Later signs include:

- Muscle weakness

- Established ischemia

Diagnosis is challenging in the unconscious patient.

A high index of suspicion should be present in all unconscious patients.

Signs

Assessment of passive toe and ankle dorsiflexion at regular intervals is mandatory in a suspected compartment syndrome affecting the lower leg.

Stretching the affected muscle groups will induce severe pain

The presence of a distal pulse does not exclude compartment syndrome.

Specific treatment principles

Incision of the fascial envelope of the compartment is performed if the diagnosis is suspected on clinical grounds.

Intracompartmental pressure measurement is not validated in children and can be misleading.

4. Fasciotomy

All four compartments of the leg must be decompressed fully by fasciotomy, using extensile surgical approaches.

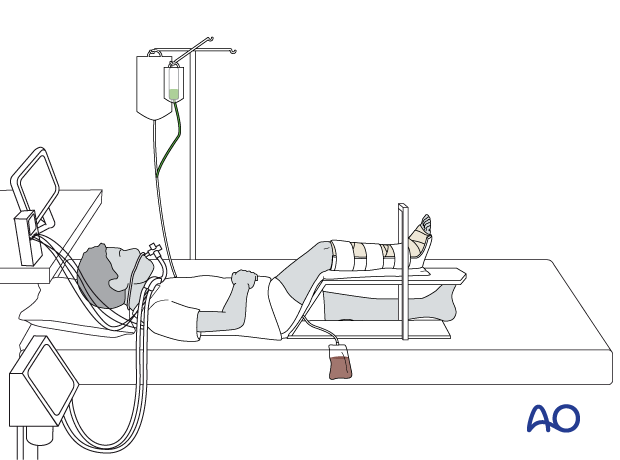

Posteromedial incision

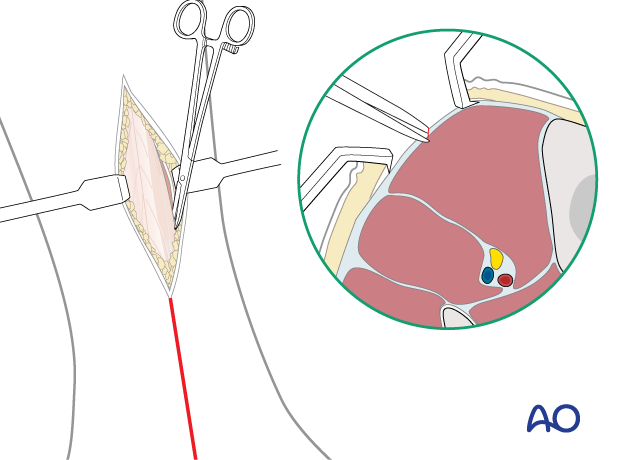

The two posterior compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision in the lower leg 1 cm posterior to the palpable posteromedial border of the tibia.

After reaching the fascia, continue dissection anteriorly to the posterior tibial margin to avoid the saphenous vein and nerve.

The deep posterior compartment here is superficial and readily accessible.

Open the fascia of the deep posterior compartment carefully distally and proximally under the belly of the soleus muscle, ensuring that the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle is not injured.

Through the same incision, open the fascia of the superficial posterior compartment proximally and distally, posterior and parallel to the incision in the fascia of the deep posterior compartment.

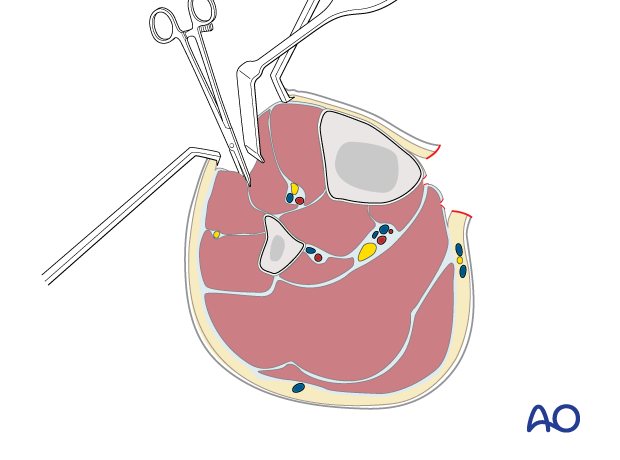

Anterolateral incision

The anterior and lateral compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision, 1 cm lateral to the anterolateral border of the tibia and long enough to expose the whole length of the compartments.

The incision protects the deep perforators, which may be required for subsequent soft tissue reconstruction.

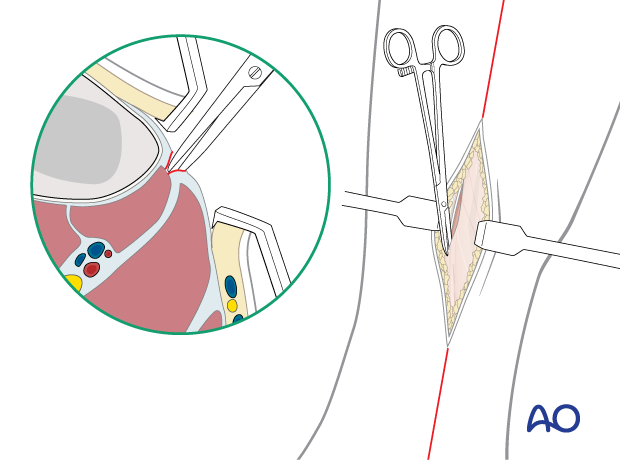

An incision is made in the fascia of the anterior compartment in line with the skin incision. The fascia is opened proximally and distally, respecting any visible superficial nerve.

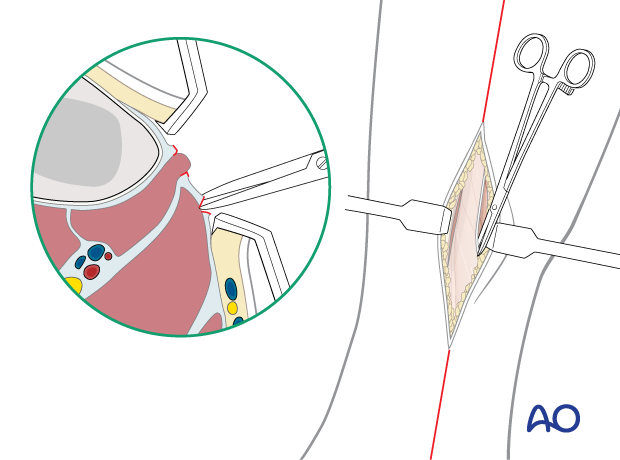

Reflecting the extensor muscles medially will expose the lateral intermuscular septum within the anterior compartment.

The lateral compartment fasciotomy is performed by dividing the lateral intermuscular septum from inside the anterior compartment.

5. Fracture fixation

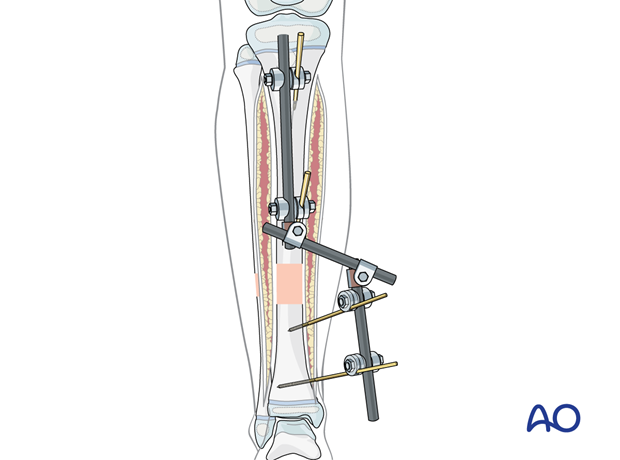

Fracture stability is important for adequate care of the injured limb, particularly if a compartment syndrome has damaged the local muscles.

Temporary external fixation can be applied.

Alternatively, internal fixation can be performed to achieve immediate definitive stabilization, if appropriate.

6. Aftercare

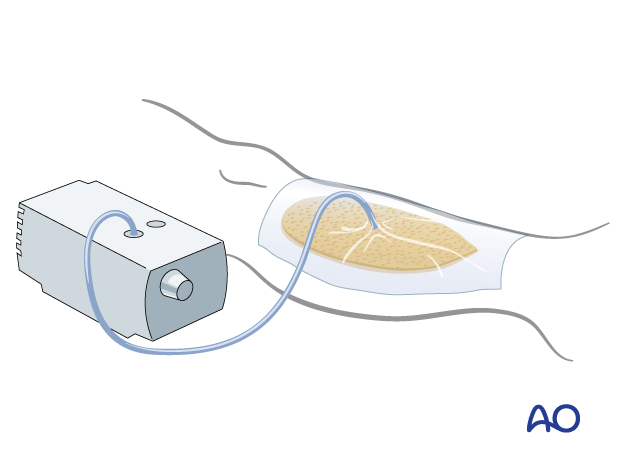

After stabilization, the fasciotomy wounds are left open.

The use of vacuum-assisted closure may decrease local swelling and reduce the size of the wound.

A bulky dressing may be applied as an alternative.

Delayed surgical closure

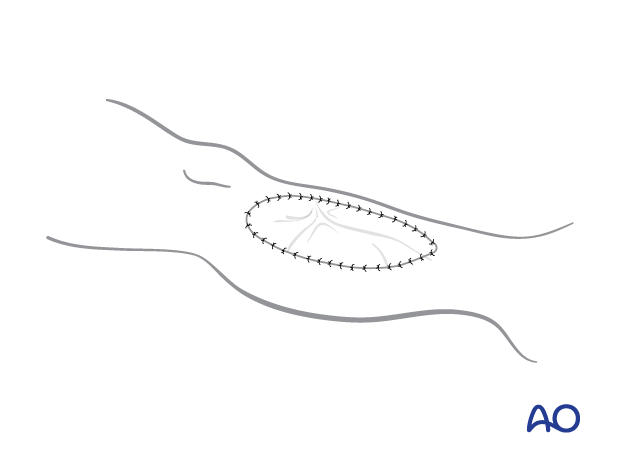

After skeletal stabilization consideration must be given to achieving skin coverage.

The simplest and safest technique is to cover the healthy soft-tissue defect with a split skin graft.

Delayed skin suturing is only permissible if it can be achieved without any skin tension.

If nerves, vessels, tendons, or periosteum are exposed, especially after debridement of unhealthy tissue, a full-thickness flap may be required.

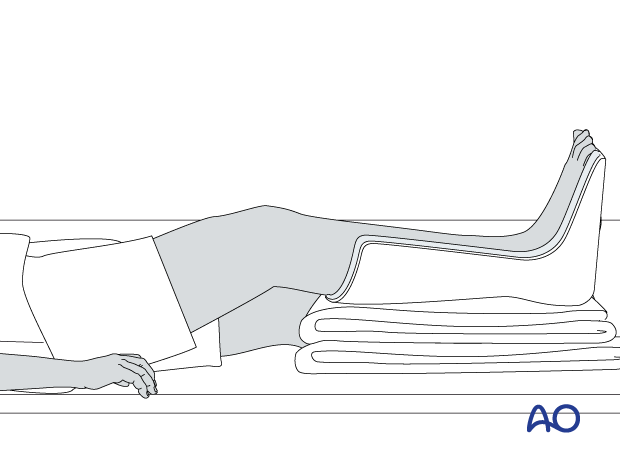

Postoperative splintage

It is important to splint the foot and ankle in a neutral or dorsiflexed position to prevent contractures.

This can be achieved with a well-padded plaster back slab or with extension of an external fixator to the foot.

Maintain toe mobility with passive stretching.