Management of associated radial nerve injuries

1. Introduction

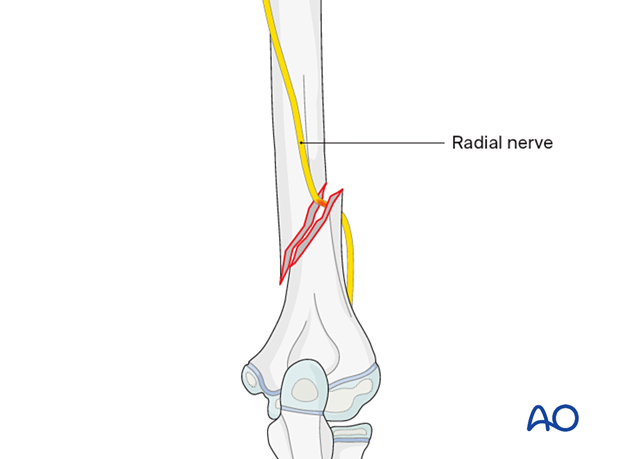

Radial nerve injury occurs in 5–10% of pediatric humeral shaft fractures.

Early diagnosis, appropriate treatment selection, and meticulous surgical technique can minimize the risk of long-term functional deficit.

2. Nerve injury types

Primary vs secondary nerve injuries

Primary injuries occur at the time of fracture due to direct trauma, stretch, or compression.

Secondary injuries occur later and are associated with compartment syndrome, hematoma, or infection.

Iatrogenic injuries can occur during fracture fixation surgery during reduction, nerve retraction, dissection, or misplacement of hardware.

3. Open vs closed fractures

Open fractures

Open fractures carry a higher risk due to direct nerve injury.

They may require early surgical exploration for both fracture fixation and nerve repair.

Closed fractures

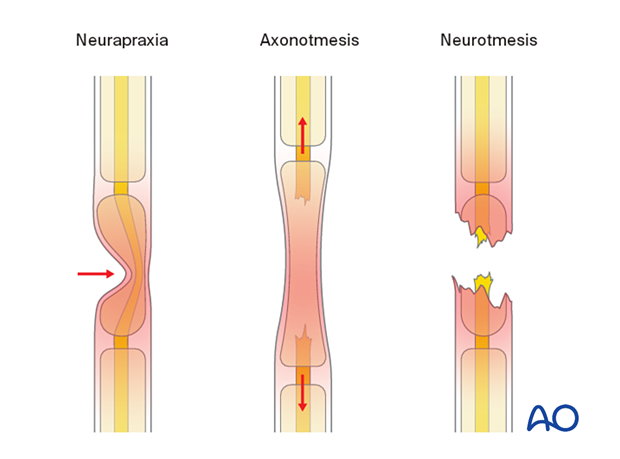

Closed fractures are more commonly associated with neuropraxia (conduction block) with potential for spontaneous recovery.

Expectant management is often the initial approach.

4. Risk by fracture type

Radial nerve injury is most commonly seen in diaphyseal injuries and is associated with the degree of displacement and comminution.

Middiaphyseal fractures are more likely to recover spontaneously as the injury is usually due to a neuropraxia. Distal third fractures are more likely to require surgical intervention due to direct nerve damage.

5. Diagnosis

Clinical presentation:

- Weakness of wrist extension (wrist drop)

- Loss of thumb extension and abduction (“thumbs-up”)

- Weakness of finger extension

Electrodiagnostic studies (electromyography (EMG)/nerve conductivity velocity (NCV)) can be used to confirm the severity and location of the nerve injury.

High resolution ultrasound can be used to differentiate between neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis.

6. Treatment

Expectant management

The initial approach for most closed fractures with neuropraxia is expectant.

Serial clinical examination is crucial and EMG/NCV monitoring may also contribute.

The first signs of recovery usually occur within 3 months and may only be detected by NCV. Full recovery can take up to 12 months.

Hand therapy including splintage is recommended in anticipation of recovery.

Surgical intervention

Surgery is indicated for:

- Nerve transection

- Open fractures

- Worsening symptoms despite expectant management

- Absence of recovery after 3 months

- Neurological signs arising after surgical fixation (especially after plating, use of cerclage wires, and application of external fixator using small stab incisions)

Surgical options include nerve exploration, repair, grafting, or neurolysis (adhesion removal).

7. Aftercare

Radial nerve palsy - Prevent contractures

Radial nerve injuries with humeral fractures usually recover and nonoperative fracture management is often appropriate for patients with these combined injuries.

It is important to include physical therapy and splinting to avoid wrist flexion and thumb adduction contractures and to maintain metacarpophalangeal extension.

The nerve is observed for progressive motor and sensory recovery.

Recovery typically begins with return of brachioradialis and the radial wrist extensor function, followed by finger extension and thumb abduction.

Electrodiagnostic testing should be considered at six weeks, if there is no clinical evidence of recovery.

If there are no clinical and electromyographic signs of recovery at 3 months, surgical exploration and neurolysis of the radial nerve at the fracture site should be considered.

8. References

- Korompilias AV, Lykissas MG, Kostas-Agnantis IP, et al. Approach to radial nerve palsy caused by humerus shaft fracture: is primary exploration necessary? Injury. 2013 Mar;44(3):323–326.

- Wiktor Ł, Tomaszewski R, Damps M. Radial Nerve Palsy Associated with Humeral Shaft Fractures in Children. Biomed Res Int. 2023 Dec 1:2023:3974604.