Closed reduction; cast fixation with/without wedging

1. Principles

Pediatric considerations

Reduction and casting of displaced fractures is performed with conscious sedation or general anesthesia in children.

The environment should be one in which the child and the parents/carers are comfortable.

Important considerations include:

- A child-sensitive approach

- A child-friendly clinical area

- Careful explanation of the procedure, in language that is understood by the child and the parents/carers

- Availability of all equipment and material

A provider familiar with pediatric sedation and airway management should take responsibility for the safety of the anesthetic.

General considerations

Forearm diaphyseal fractures require a long arm cast to control forearm rotation and therefore decrease the risk of displacement.

Correct molding of the cast helps to prevent redisplacement of the fracture.

If a complete cast is applied in the acute phase after injury, it is safer to split the cast down to skin over its full length.

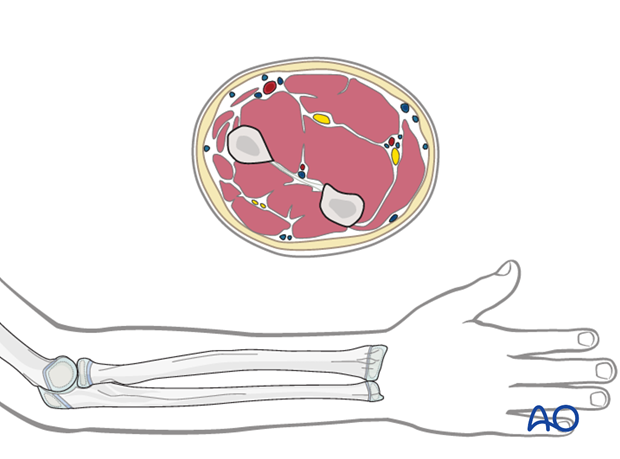

An understanding of the forearm surface anatomy particularly bony prominence and the cross-sectional contour is important for effective reduction and safe application of a cast. Read more here.

Periosteum as a factor in fracture stability

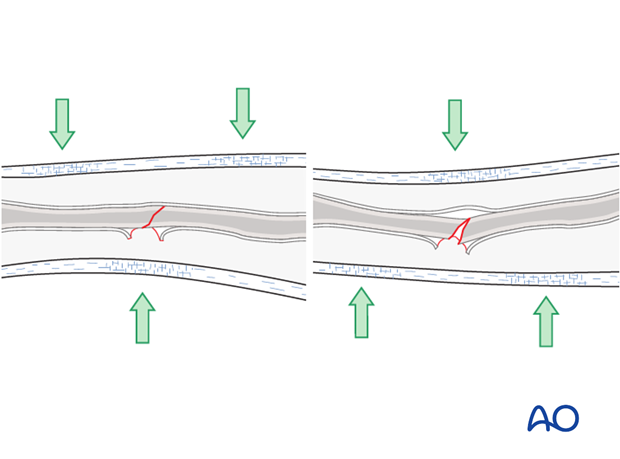

Children’s periosteum is a thick, tough tissue and is often intact on the concave (compression) side of a fracture.

This confers extra stability with three-point molding as the concave side periosteum acts as a tension band.

Cast wedging

Cast wedging is useful for correction of angular deformities that are residual or recurrent after cast application.

The best indication is both bone fractures with similar fracture levels.

Wedging a cast is more controlled than removing and reapplying it.

The optimal time is about 14 days because there is moldable callus.

2. Preparation for cast application

Equipment

- Examination couch

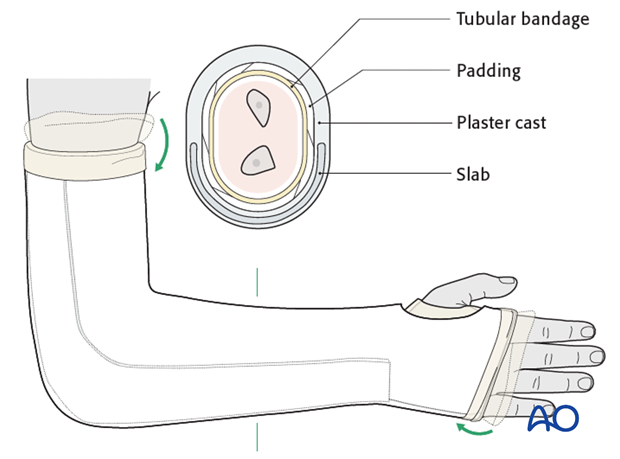

- Tubular bandage (40-80 mm wide, depending on the size of the child)

- 2-4 rolls of padding (40-150 mm wide, depending on the size of the child)

- 2-8 plaster of Paris (POP) or synthetic fiberglass bandages (40-150 mm wide, depending on the size of the child)

- Malleable (thermoplastic, leather, or lead) strip

- Bucket with cold water

- Protective aprons for the team members and the child

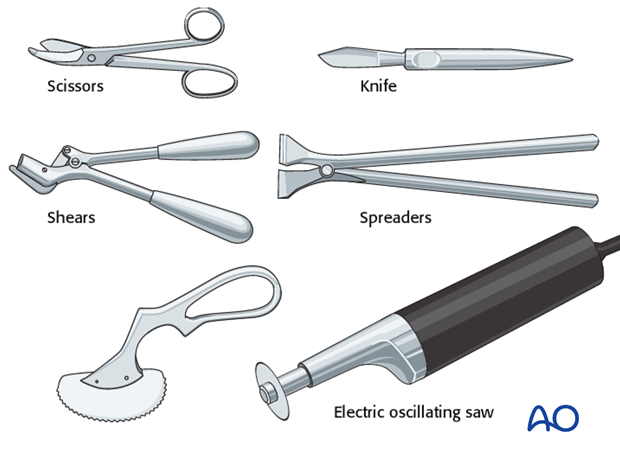

- Appropriate equipment to cut, split, or remove the cast

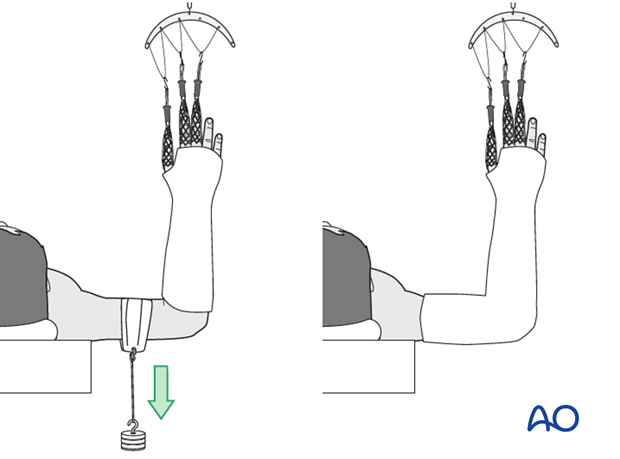

- Finger traps and a pole to suspend them

- A strap and weights for traction

- C-arm if available

Patient preparation

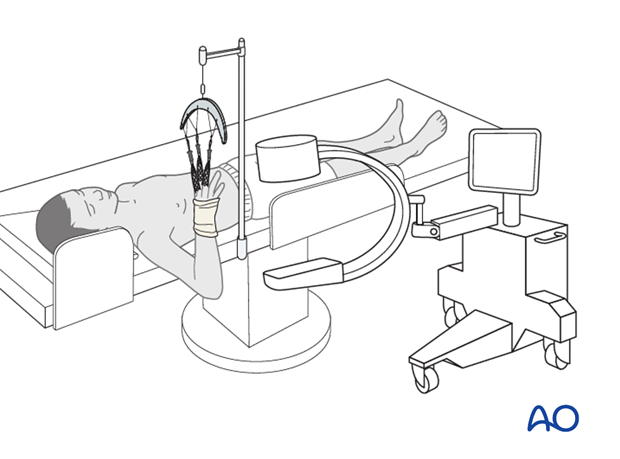

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a supine position.

Convenient OR setup for single surgeon work is illustrated here.

Apply a tubular bandage.

Apply traction using a strap and weights.

Holding the arm using finger traps as illustrated allows easy manipulation, reduction, imaging and mobilization for a surgeon working without an assistant.

To avoid damage to the skin of the fingers ensure that the pressure is evenly distributed and that prolonged or excessive force is avoided.

3. Closed reduction of bowing

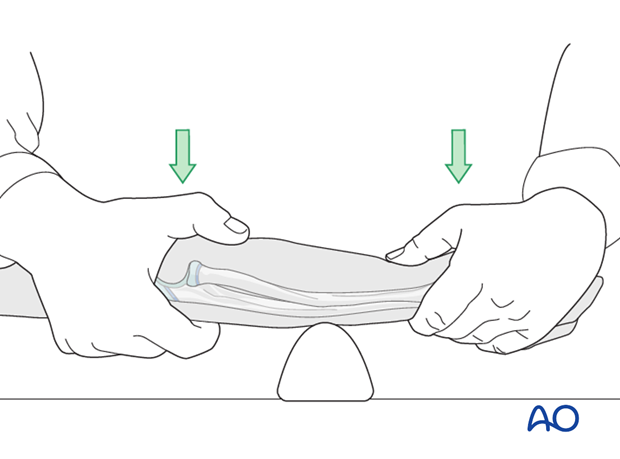

Apply prolonged and direct force for several minutes to reverse the bowing.

It is not helpful to reduce the deformity of the bone only briefly as it will spring elastically back into its deformed shape.

Depending on the size of the child and the direction of the deformity, apply three-point bending with a thumb, knee or a firm folded towel as a fulcrum.

4. Closed reduction of greenstick fractures

A greenstick fracture is readily identifiable by substantial but stable angular deformation at presentation.

After conscious sedation it is straight forward to correct the angular deformity. A crack is heard when the reduction is completed. Intact periosteum on the concave side confers considerable stability with correct three-point molding.

5. Closed reduction of complete fractures

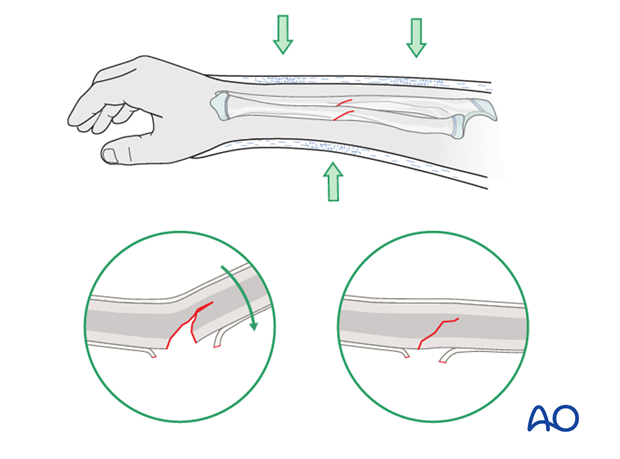

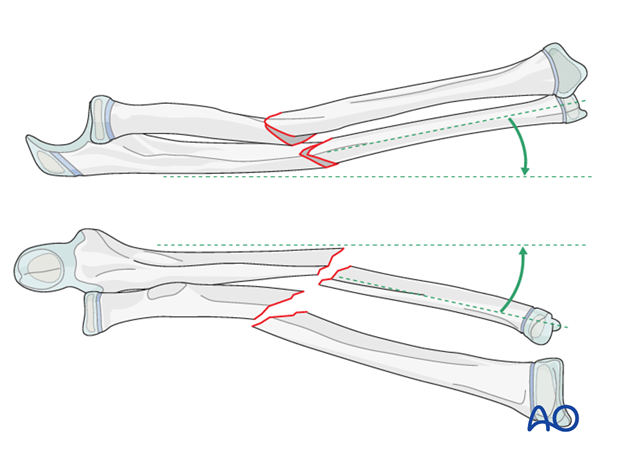

Reduction of angular deformity

Prior to attempting the reduction, analyze the fracture displacement completely.

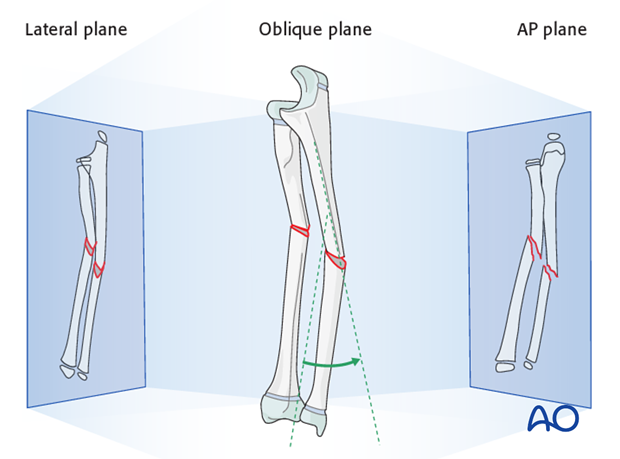

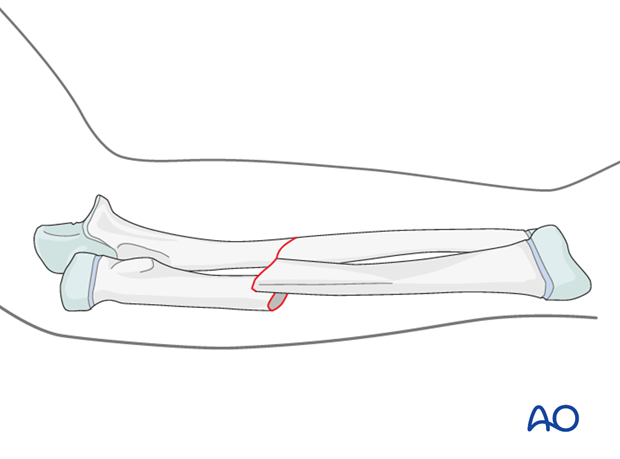

Forearm fractures predominantly have angular displacements which are conventionally described in two planes, apex volar/dorsal or apex medial/lateral.

In reality most fractures have a single oblique plane and determining the direction of this plane by evaluating the x-rays and the arm often allows a simple reduction maneuver.

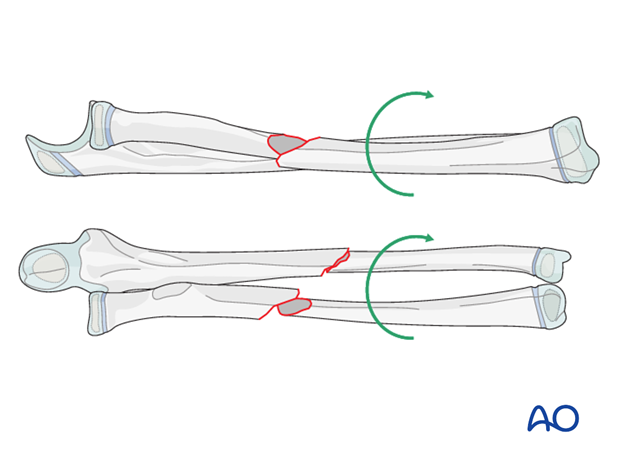

Reduction of rotational deformity

Displacement in the axial plane (rotational deformity) is often overlooked but can be assessed with x-rays and from the arm position.

Rotational deformity often exists when the radius and ulna are fractured at different levels.

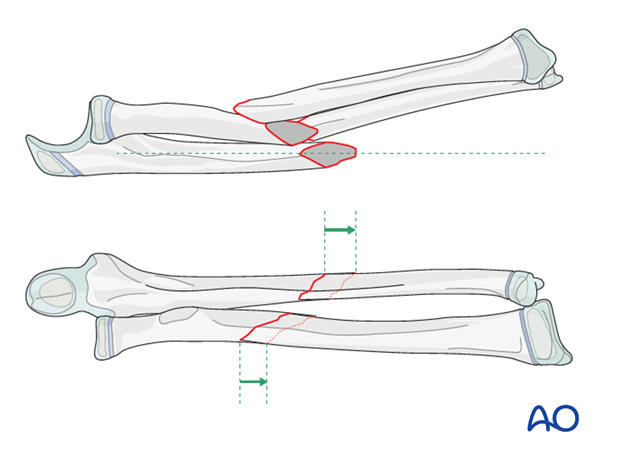

Reduction of translational deformity

The most common translational deformities are bayonet apposition and shortening which often occur together. Anatomical reduction should be obtained to maximize stability within the cast.

Reduction maneuvers

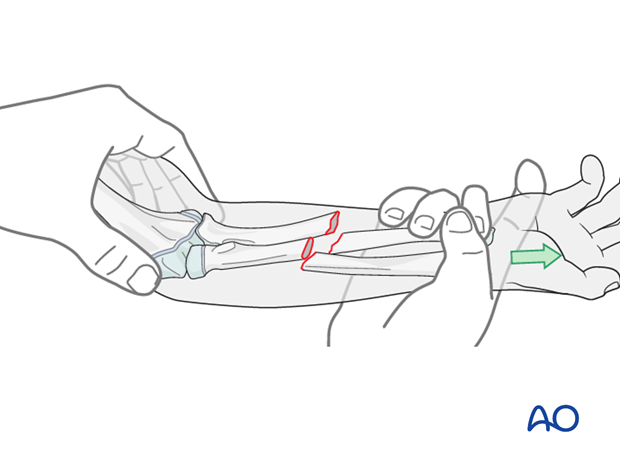

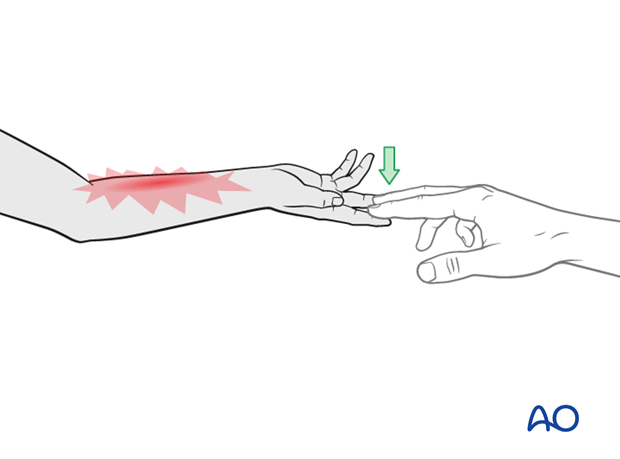

With the arm in finger traps and traction applied, grasp the humeral epicondyles to stabilize the proximal fragment.

Grasp the distal radius to provide longitudinal traction and simultaneous reduction of angular and rotational displacements.

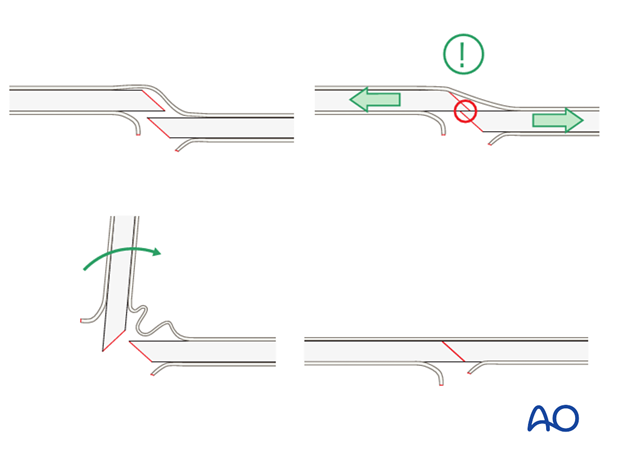

If one of the fractures is transverse, try to feel the distal end hook on to the proximal end before correction of the angulation.

Periosteum as a factor in reduction

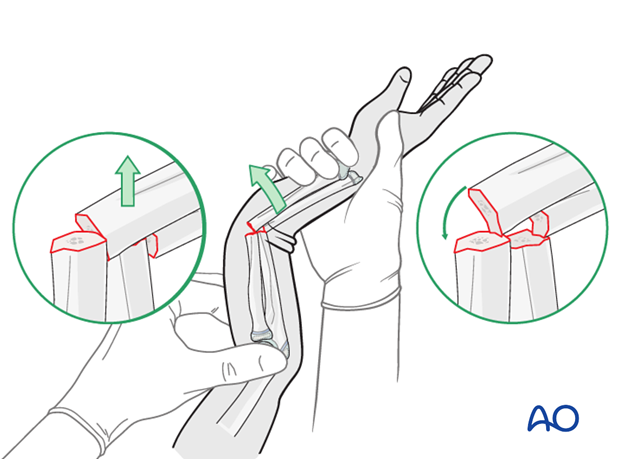

Intact periosteum on the concave side of a fracture may prevent reduction by traction alone.

Exaggerating the initial deformity loosens the periosteum allowing for gentle reduction of the fracture.

Evaluation of reduction

Position the arm in a neutral rotation.

Evaluate the reduction by physical examination and C-arm if available.

Adjust the reduction if necessary.

Note: For younger children bayonet apposition of a transverse fracture is acceptable if it is not possible to obtain anatomical reduction.

6. Cast application

Removal of traction

If the fracture is stable after reduction, the traction can be removed, and the entire cast can be applied at once.

Pearl: Apply cast in sections

If traction is needed to hold the reduction the forearm portion of the cast can be applied first and extended above the elbow after the traction strap has been removed.

Some surgeons prefer not to use traction and apply the upper arm section as far as the elbow to stabilize the proximal fragments prior to reduction.

Arm position

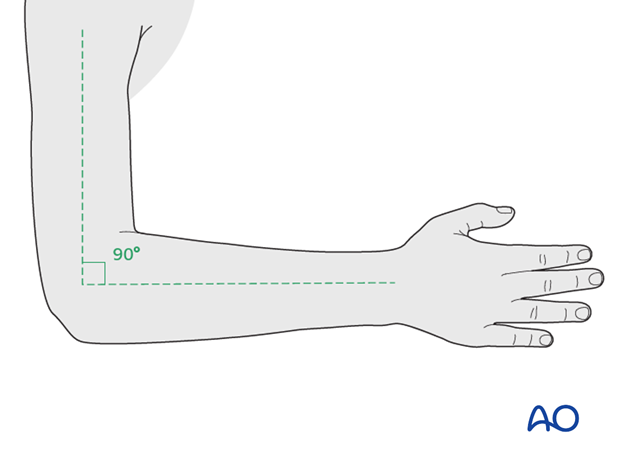

Flex the elbow to 90° prior to application of the tubular bandage and padding, to avoid compression at the antecubital fossa.

Place the forearm in neutral rotation for undisplaced, stable fractures.

Preparation for splitting the cast

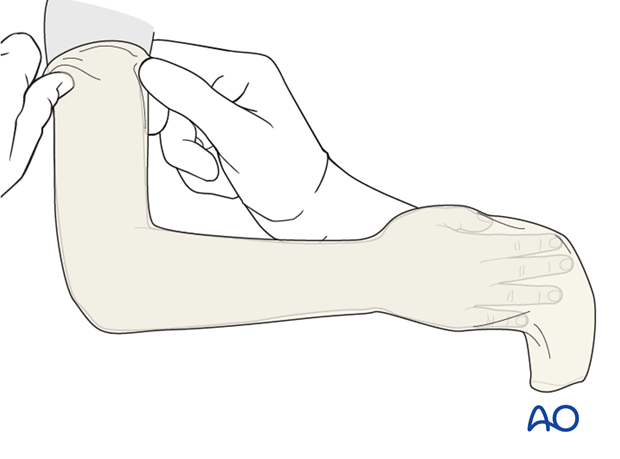

A temporary malleable (thermoplastic, leather or lead) strip can be placed beneath the tubular bandage, prior to plaster application, to protect the skin when plaster splitting is required.

The location of the strip should be planned to avoid areas of molding.

Application of tubular bandage

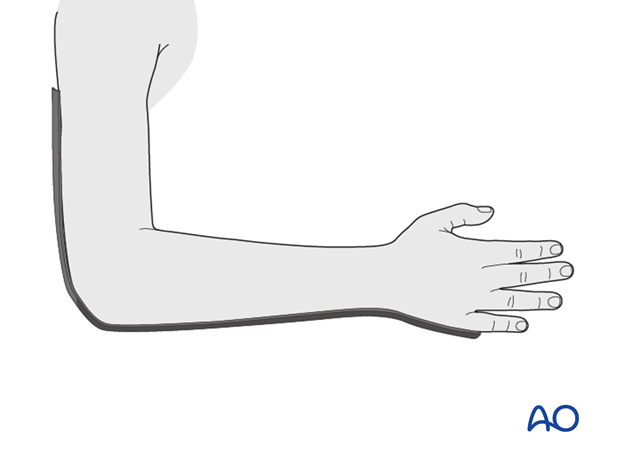

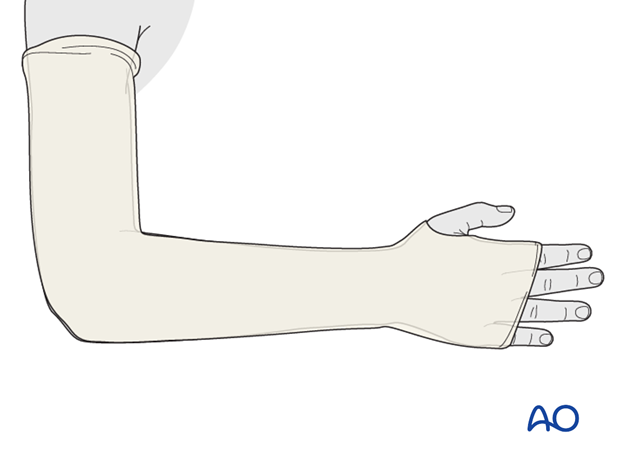

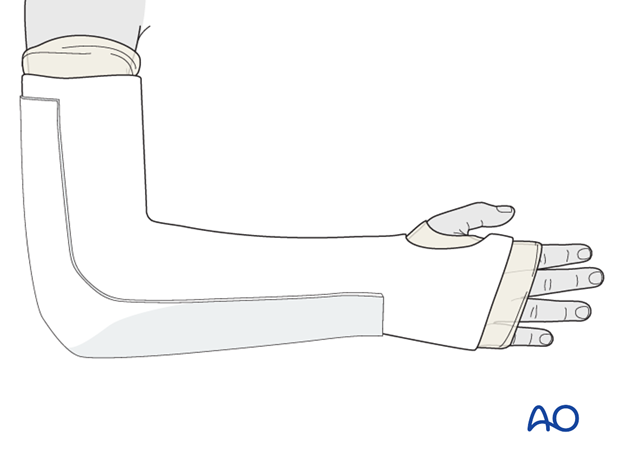

Apply a tubular bandage, directly onto the skin and malleable strip, from the axillary crease to just distal to the MCP joints allowing sufficient bandage for protection of the cast edges.

Cut a hole for the thumb.

Application of padding

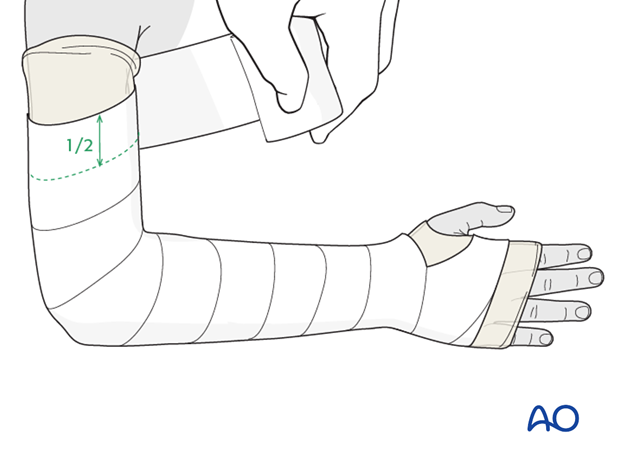

Apply a single layer of padding from the MCP joints of the fingers and thumb to the axillary crease.

Overlap each layer by 1/2.

Apply extra padding over pressure areas, including the olecranon.

Take care not to constrict the antecubital fossa.

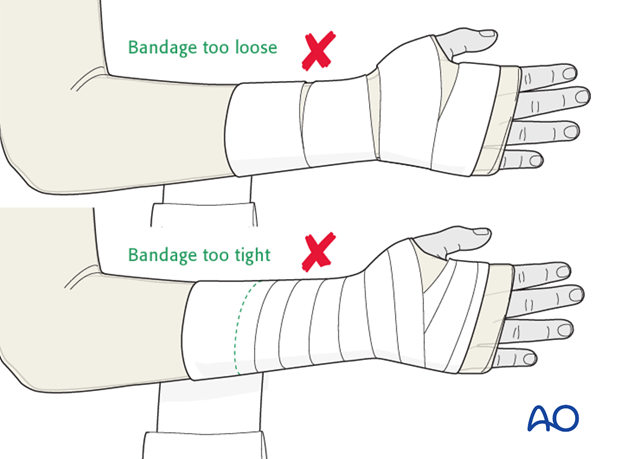

The tubular bandage and padding should be applied without creases.

Consistent firm but not tight wrapping should result in a neat stable layer of padding that does not constrict the arm.

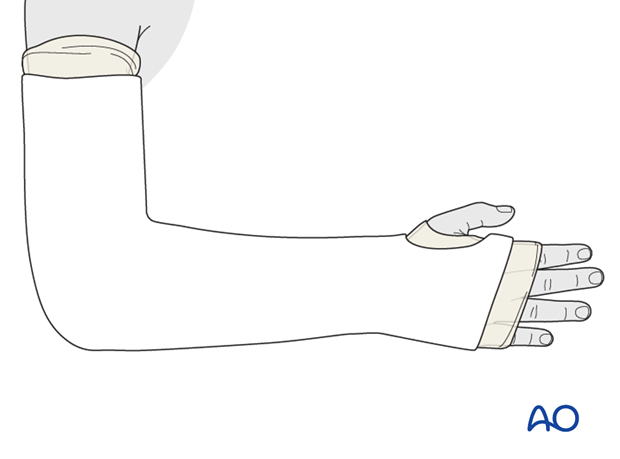

Application of plaster

Immerse the POP/fiberglass bandage for 5-10 seconds and then remove excess water by gentle squeezing.

Apply a first layer of circumferential POP/fiberglass.

The plaster extends distally to the metacarpal heads and palmar flexor crease and proximally to just distal to the axillary crease.

Trim excess plaster to accommodate the thumb and fingers.

Apply a slab the width of the forearm over the ulnar aspect and the posterior humerus.

Completion of plaster cast

Fold the proximal and distal ends of the tubular bandage over the cast and cover the cast with an additional single layer of POP/fiberglass bandage.

Ensure that the edges of the cast are well-padded and smooth, to avoid abrasion during the period of plaster immobilization.

Molding the cast

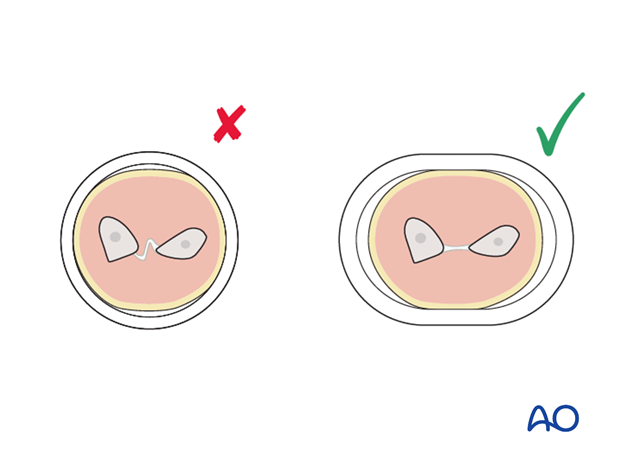

For an undisplaced fracture the cast should be molded to an oval cross-section to match the shape of the forearm.

To prevent displacement, ensure that the ulnar border of the cast is straight or molded to provide a three-point fixation, against the anticipated direction of displacement.

The assistant should support the limb until the cast is hardened.

7. Final assessment

X-ray confirmation of reduction

Take an x-ray in both AP and lateral view.

Anatomical reduction in both planes should be the aim of treatment.

Whilst it is pragmatic to accept small degrees of deformity in some cases, this should be considered on an individual basis.

Factors which influence this decision include patient age, location and pattern of fracture.

X-ray evaluation of the cast

An x-ray of a well applied forearm cast will show:

- A cast index of 0.7 or less (width on lateral view/width on AP view; CI = A/B)

- Correctly applied three-point molding

- The ulnar border of the cast should be straight.

- If the ulnar border is convex there is a high likelihood that both bones will displace with gravity into an apex ulnar position.

- Dense material where the mold has been applied, but no bumps or wrinkles

Compartment syndrome

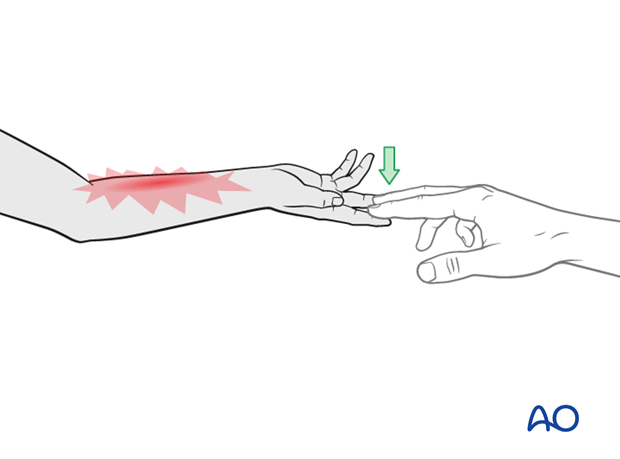

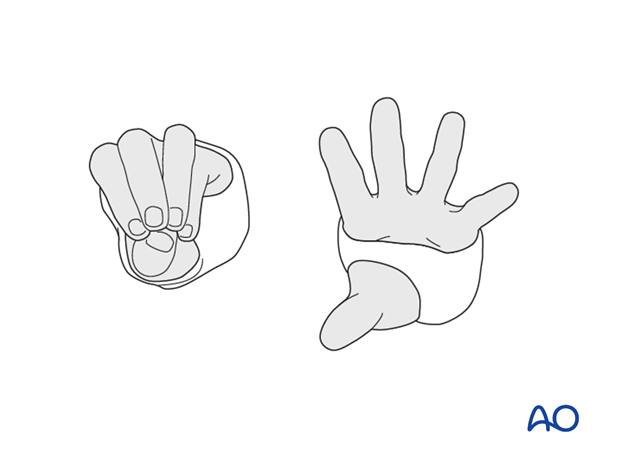

The ability to fully extend the fingers passively, or actively, without discomfort indicates absence of muscle compartment ischemia.

Flexion of MCP joints

Care should be taken to ensure that the plaster cast does not restrict flexion of the MCP joints.

Sling

The arm is supported in a broad arm sling.

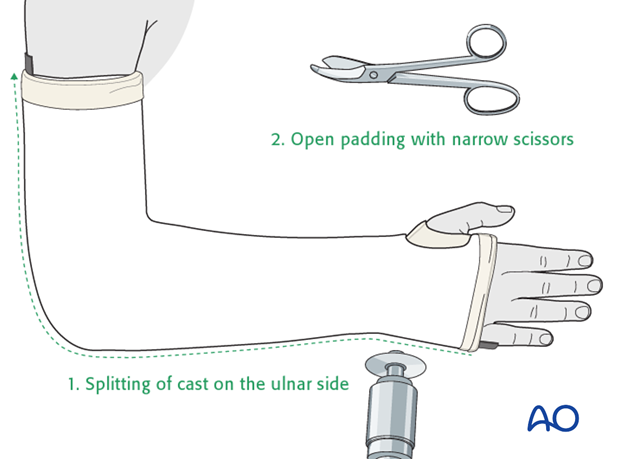

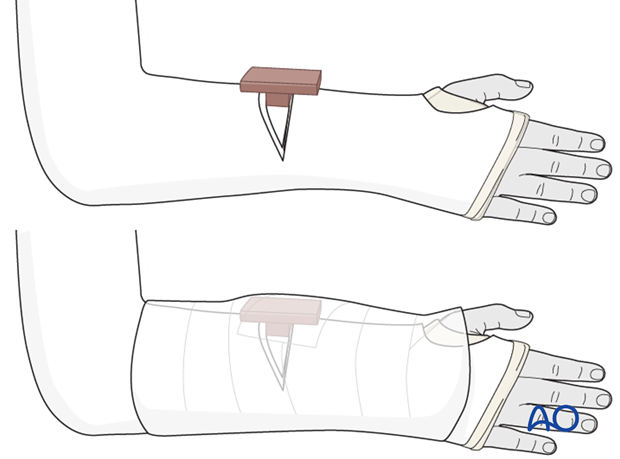

8. Cast splitting

When required, the plaster should be split along the entire length.

Once the cast is hardened, mark it, then split using an oscillating saw, a hand saw, or a sharp plaster knife (1).

Take great care to avoid injury to the underlying skin.

Widen the split with a cast spreader. Then divide the underlying padding with scissors (2) and remove the protective strip to expose the skin.

Apply a crêpe bandage to protect the split cast.

When the swelling has subsided (after 5-7 days), complete the cast with a single POP bandage.

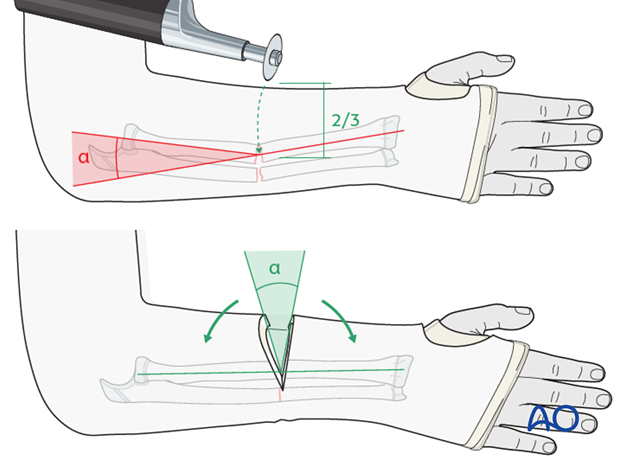

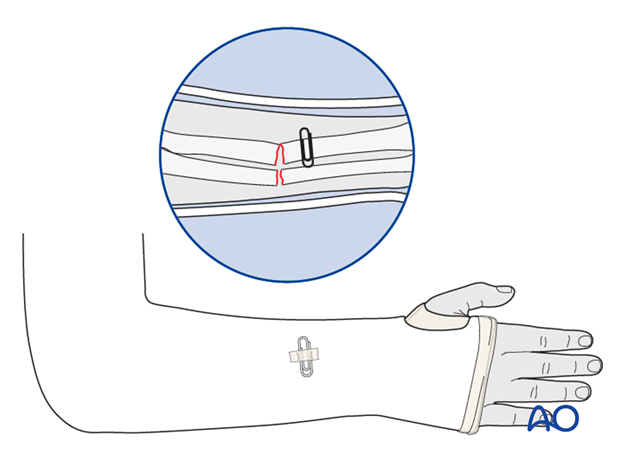

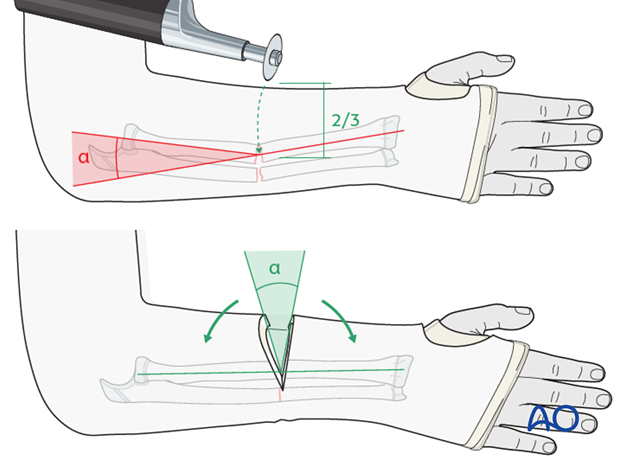

9. Cast wedging

Take an x-ray with a paper clip or other metal marker taped to the cast at the fracture level.

Measure the angular deformity in two planes and calculate or estimate the true (oblique plane) deformity.

Cut 2/3 of the circumference of the cast leaving a hinge on the concave side of the deformity.

Bend the cast to open by an amount that creates the desired angle, which is easily drawn on the x-ray.

Apply a wooden T-shaped block or cork into the opening to hold the correction.

Overwrap the cast with a new layer of POP/fiberglass cast.

10. Aftercare following closed management

Duration of immobilization

Diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna usually require 4-6 weeks of immobilization for adequate callus formation (see also the additional material on healing times).

Analgesia

Ibuprofen and paracetamol should be administered regularly during the first 4-5 days of injury, with additional oral narcotic medication for breakthrough pain.

If the level of pain is increasing the child should be examined.

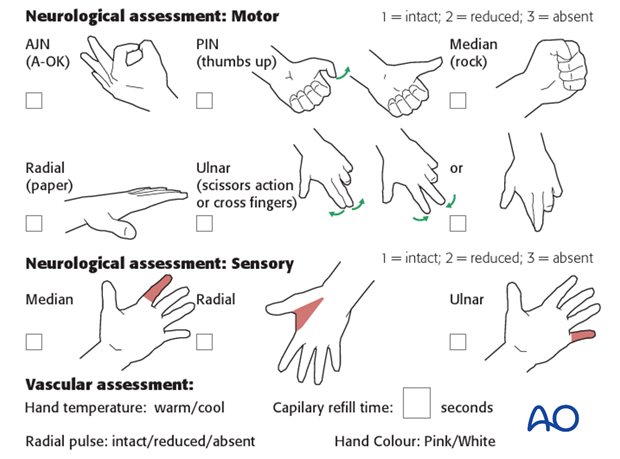

Neurovascular examination

The child should be examined regularly, to ensure finger range of motion is comfortable and adequate.

Neurological and vascular examination should also be performed.

Compartment syndrome should be considered in the presence of increasing pain, especially pain on passive stretching of muscles, decreasing range of active finger motion or deteriorating neurovascular signs, which are a late phenomenon.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a possible early postoperative complication that may be difficult to diagnose in younger children.

The presence of full passive or active finger extension, without discomfort, excludes muscle compartment ischemia.

If there are signs of a compartment syndrome in a child in a cast or splint:

- Split the cast, along its full length, down to skin level.

- Elevate the limb.

- Encourage active finger movement.

- Reexamine the child after 30 min.

If a definitive diagnosis of compartment syndrome is made, then a fasciotomy should be performed without delay.

Discharge care

When the child is discharged from the hospital, the parent/carer should be taught how to assess the limb.

They should also be advised to return if there is increased pain or decreased range of finger movement.

It is important to provide parents with the following additional information:

- The warning signs of compartment syndrome, circulatory problems and neurological deterioration

- Hospital telephone number

- Information brochure

For the first few days, the elbow and forearm can be elevated on a pillow, until swelling decreases and comfort returns.

When the limb is comfortable, the child may use a sling but many children are more comfortable without support.

Follow-up x-rays

AP and lateral x-rays may be taken to assess fracture position at intervals decided by the fracture configuration and age of patient.

Loss of reduction can be treated by cast wedging, further manipulation or conversion to internal fixation.

Removal of cast or splint

Fractures treated by closed reduction should have the cast removed 4-6 weeks after the injury.

Clinical assessment and x-rays without the cast are used to judge adequate healing.

Recovery of motion

As symptoms recover, the child should be encouraged to remove the sling and begin active movements of the forearm.

The majority of forearm motion is recovered rapidly and within two months of cast removal.

The older child may take a little longer.

Once the child is comfortable, with a nearly complete range of motion, (s)he may incrementally resume noncontact sports.

Resumption of unrestricted physical activity is a matter for judgment by the treating surgeon.

Shaft fractures treated closed are at risk of refracture for 6 months after injury.