Compartment syndrome

1. Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a true surgical emergency. Failure to diagnose and to institute urgent treatment by decompression usually results in major limb disability.

In compartment syndrome increasing tissue pressure prevents capillary blood flow and produces ischemia in muscle and nerve tissue. The process is progressive and leads to necrosis with permanent loss of function.

Treatment of compartment syndrome requires surgical release of the closed osteo-fascial compartment by wide and lengthy division of the skin and fascial envelope.

Incidence

Muscle compartment syndrome is a relatively common occurrence in the osteofascial compartments of the calf. It also may occur in other anatomical compartments. Other common sites are the forearm, thigh, foot and hand. It may be associated with supracondylar humeral fractures in children. Muscular young adult males are at particular risk.

A metanalysis of tibial shaft fractures has revealed that the overall risk of compartment syndrome following these injuries varied across studies from 2.7%–15.6% (OTD March 2010).

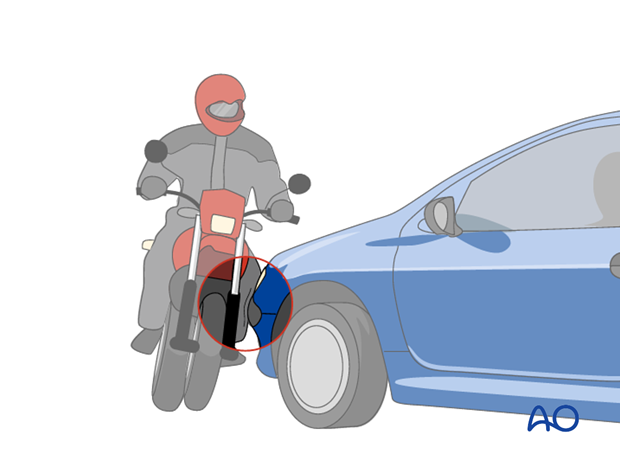

Causes

Muscle compartment syndrome occurs most commonly after high-energy limb injuries. However, it can occur after apparently trivial injuries, with or without fractures, or elective extremity surgery. Crushing injuries are at high risk of compartment syndrome. Certain other insults, such as burns, or prolonged compression (as may occur in a comatose, unprotected patient), may also cause muscle swelling and precipitate the syndrome.

A further cause can be edema from abnormal capillary permeability caused by reperfusion after prolonged ischemia. Tight bandages, splints, or casts can also elevate compartmental pressure and contribute to development of compartment syndrome.

2. Pathophysiology

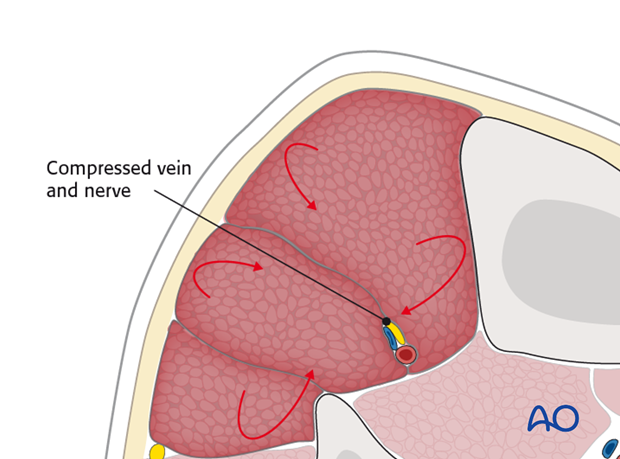

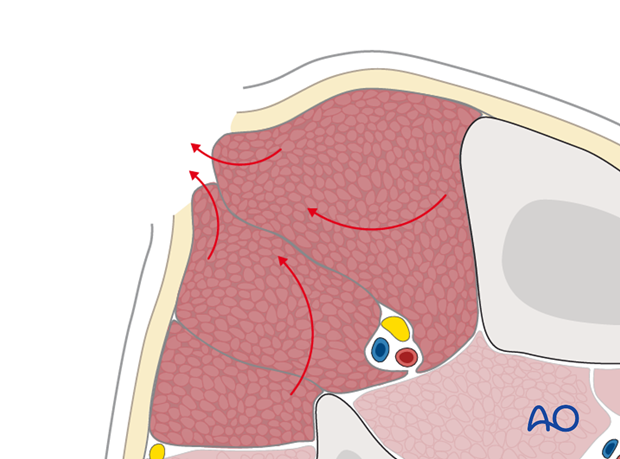

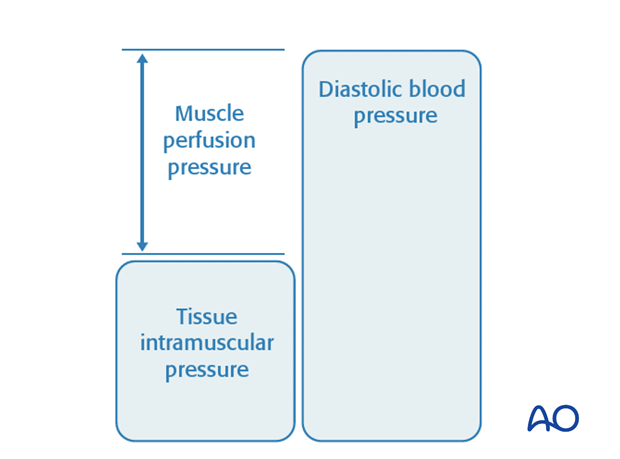

- Compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure within a closed osteo-fascial muscle compartment rises above a critical level. This critical level is the tissue pressure which collapses the capillary bed and prevents low-pressure blood flow through the capillaries and into the venous drainage. Normal tissue pressure is 0-10 mm Hg. The capillary filling pressure is essentially diastolic arterial pressure. When tissue pressure approaches the diastolic pressure, capillary blood flow ceases. A number of studies have shown that

- if diastolic arterial pressure is not more than 30 mm Hg above tissue pressure, compartmental capillary blood flow is significantly obstructed and severe hypoxia occurs in muscle and nerve tissue.

- The critical measurement is muscle perfusion pressure (MPP), the difference between diastolic blood pressure (dBP) and measured intramuscular tissue pressure. (MPP has also been called "Delta P", to indicate the difference between diastolic blood pressure and intramuscular pressure.) This difference in pressure reflects tissue perfusion far more reliably than the absolute intramuscular pressure.

- Muscle tolerates short periods of hypoxia, but after a few hours, progressive necrosis begins.

- An arterial injury may cause compartmental tissue ischemia. After blood flow is restored, capillaries leak and ischemic muscle swells. Reperfusion injury is another cause of compartment syndrome.

3. Diagnosis

Symptoms

The diagnosis of this severe complication rests on two factors: a high index of suspicion and a thorough understanding of its variable clinical presentation.

In a conscious and alert patient, there will be unrelenting, worsening pain, greater than expected for the particular injury, and not related to limb position.

Commonly there is a relatively pain-free interval, perhaps a few hours following fracture treatment, before such pain develops.

The level of pain can often be judged by increasing requests for ever-stronger analgesia, or increasing use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) systems.

Any nerve traversing the involved compartment will become hypoxic, often causing numbness and tingling in the nerve distribution. After some hours, ischemic nerves cease to function and the pain resolves.

Signs

Clinical signs of an impending muscle compartment syndrome include tenderness and induration of the affected compartment, increase in the pain on passive muscle stretching, possible sensory (and later motor) deficit in the territory of a nerve traversing the compartment and muscle weakness.

The presence of a distal pulse does not exclude compartment syndrome, because in a normotensive patient the muscle pressure rarely exceeds the systolic level.

In an unconscious, drugged, or intoxicated patient, it is easy to miss a compartment syndrome. Any visible limb swelling becomes a vital clue as does persistent, unexplained tachycardia. For such patients, direct tissue pressure measurement is very helpful for diagnosis.

Investigation

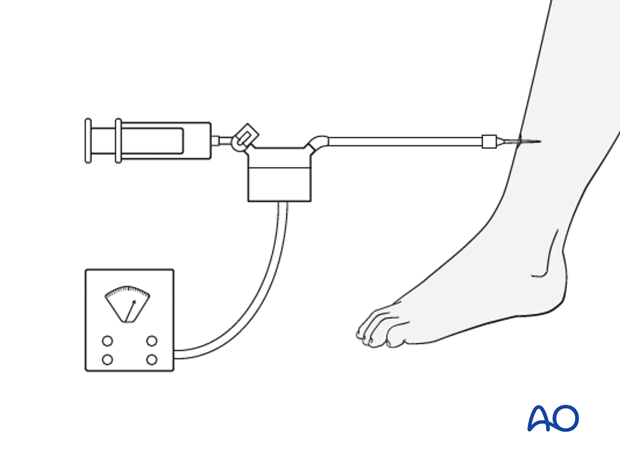

Intracompartmental pressure measurement

When compartment syndrome is obvious, there is usually no benefit to measuring pressures and immediate fasciotomy can be undertaken.

When the diagnosis is unclear, or possibly absent, compartment pressure measurement may be confirmatory, or prevent unnecessary fasciotomy.

Various techniques are now available to measure the intracompartmental tissue pressure.

All trauma surgeons should adopt a technique which is available for them and their team. This might involve use of a commercially available compartmental pressure device, a mercury manometer, large-bore needle and connecting tubing (after Whitesides), or an electronic strain gauge used for physiologic monitoring in ICU, or OR.

If the necessary equipment is not available for direct pressure measurement within the muscle compartment, then the diagnosis must be assumed if there is a reasonable clinical suspicion.

4. Treatment

Timing

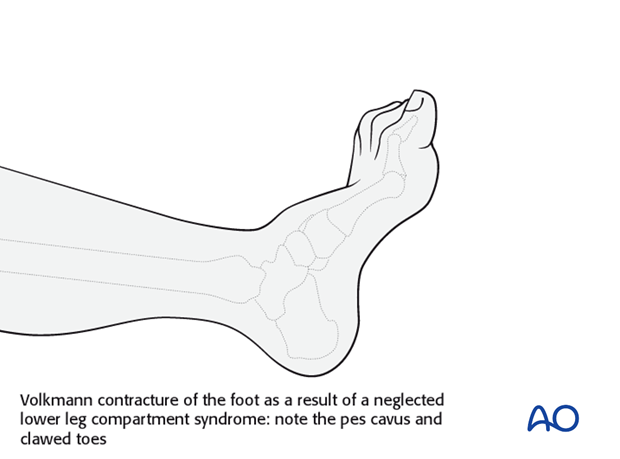

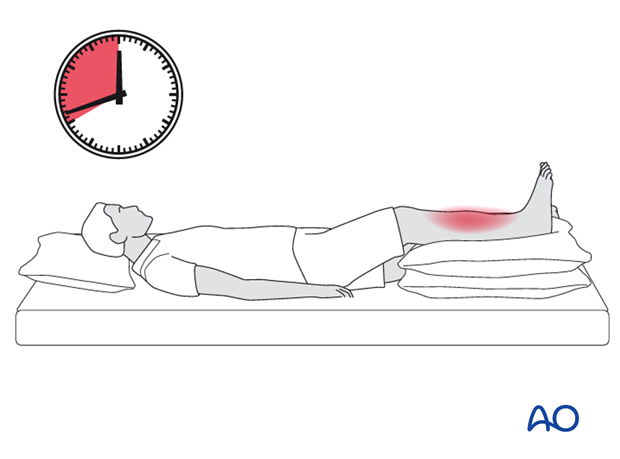

In established muscle compartment syndrome, the hypoxic muscle will become necrotic within hours. It is generally accepted that after 6-8 hours of inadequate muscle perfusion pressure (MPP), extensive muscle necrosis is likely and effective release of the muscle compartments involved is unlikely to avoid severe muscle contracture. Similarly any peripheral nerve passing through the compartment is likely to suffer permanent functional impairment.

It is therefore of paramount importance that the compartment hypertension be released as an emergency intervention.

If diagnosed within 8 hours

The only appropriate treatment is dermato-fasciotomy of all involved compartments.

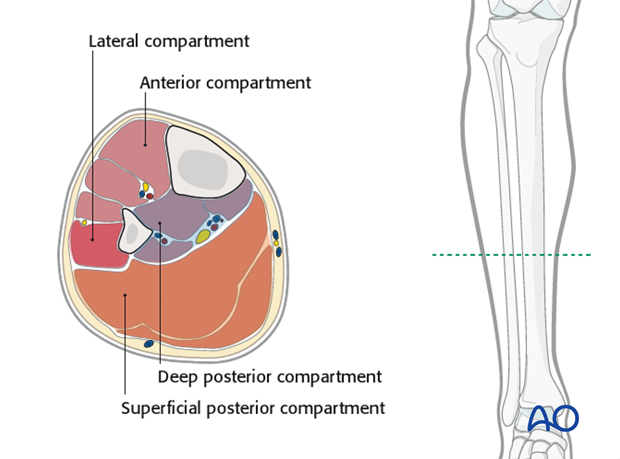

In the lower leg, one, or more of the four osteofascial muscle compartments may be involved. Typically, with an acute compartment syndrome, it is safest to release all four four compartments.

Either of two techniques should be used.

- The first is Mubarak’s double-incision technique.

- The second option is the parafibular single-incision fasciotomy described by Matsen.

Fibulectomy/fasciotomy, described in the vascular surgical literature, is contraindicated for trauma patients.

Late diagnosis

There is some limited evidence in the published literature that in delayed cases, where there is already extensive muscle death, dermato-fasciotomy has a high risk of infection of the dead tissue, septicaemia and, in some cases, death. There appears to be a high amputation rate in such cases.

Where recognition of an established compartment syndrome is delayed for more than 8-10 hours after probable onset, the decision to perform a dermato-fasciotomy requires judgment by the most experienced surgeon available.

This situation is common after mass disasters (e.g. earthquake). Exposure of partially necrotic muscle produces a wound with high risk of infection.

5. Double-incision, 4-compartment dermato-fasciotomy after Mubarak

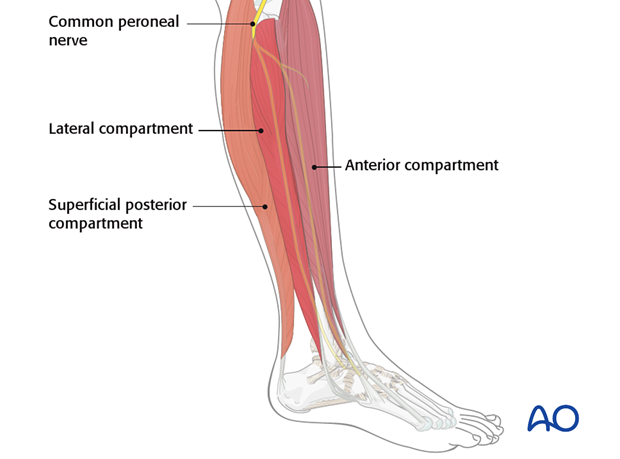

Relevant anatomy (muscles)

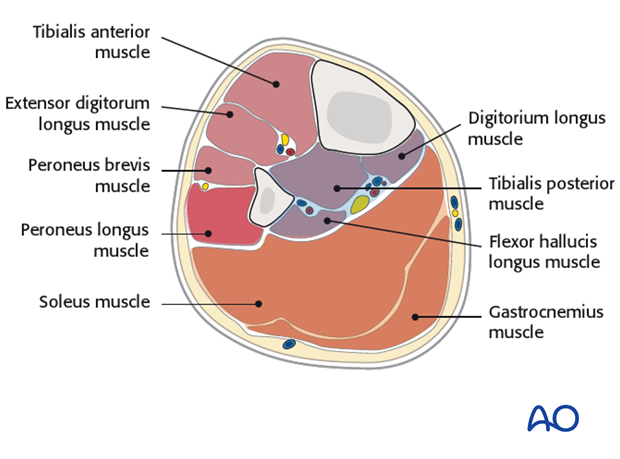

The anterior and peroneal muscle compartments are approached via an anterolateral incision: the superficial and deep posterior compartments are approached through a separate medial incision.

A good knowledge of the disposition of the four compartments and the muscles within them is essential to safe decompression.

It is important to protect subcutaneous nerves, particularly the common peroneal where it crosses the fibula proximally.

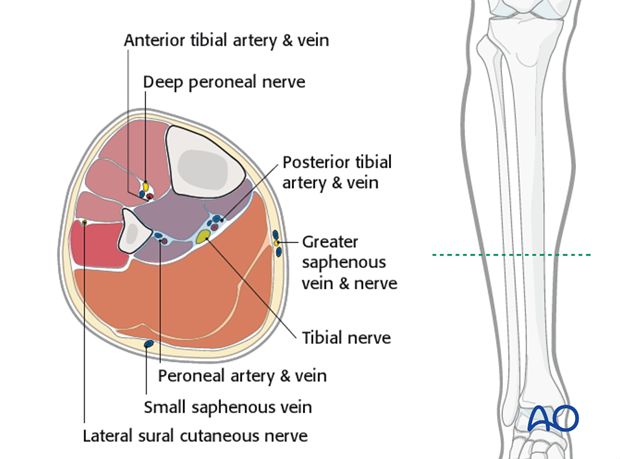

Relevant anatomy (neurovascular structures)

The principle superficial neurovascular structures at risk in these approaches are, medially, the great saphenous vein and its accompanying nerve, and laterally, the superficial peroneal nerve. The superficial peroneal nerve branches from the common peroneal nerve near the neck of the fibula and passes between the peroneus longus and brevis muscles, supplying motor branches to these muscles. The superficial branch then continues onto the dorsum of the foot to supply sensory fibers to the skin there.

The main deep neurovascular bundle at risk is the posterior tibial, as it lies on the posterior aspect of the tibialis posterior and flexor digitorum longus muscles, and medial to the belly of flexor hallucis longus. Remember this is more superficial at the medial ankle.

Technique

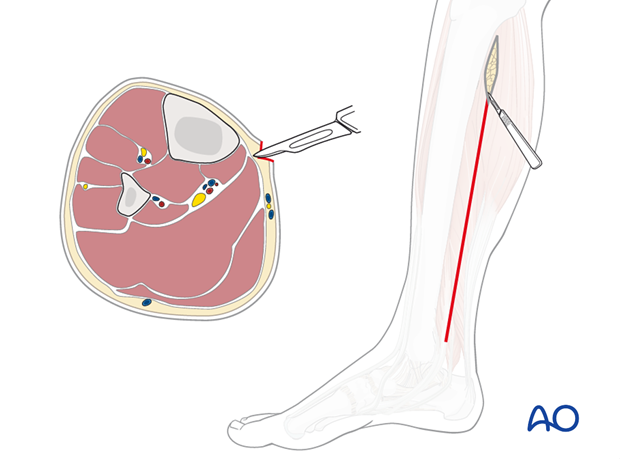

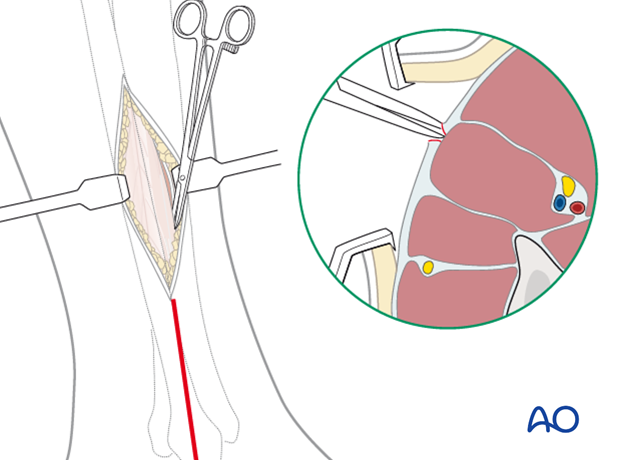

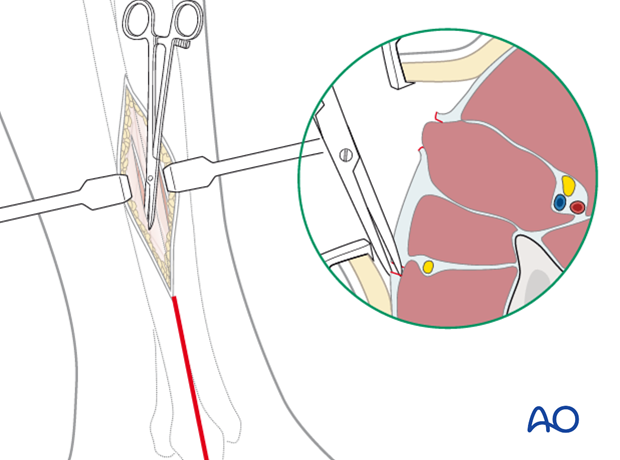

Posteromedial Incision

The two posterior compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision in the lower leg, two centimeters behind the palpable posteromedial edge of the tibia.

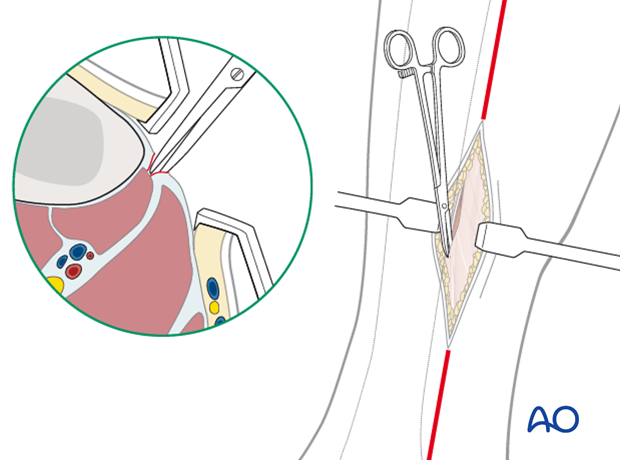

After reaching the fascia, undermine anteriorly to the posterior tibial margin, in order to avoid the saphenous vein and nerve. The deep posterior compartment here is superficial and readily accessible.

The fascia of the deep posterior compartment is carefully opened distally and proximally, under the belly of the soleus muscle, paying special attention to the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle.

Through the same incision, the fascia of the superficial posterior compartment is opened widely, two centimeters posterior and parallel to the incision in the fascia of the deep compartment.

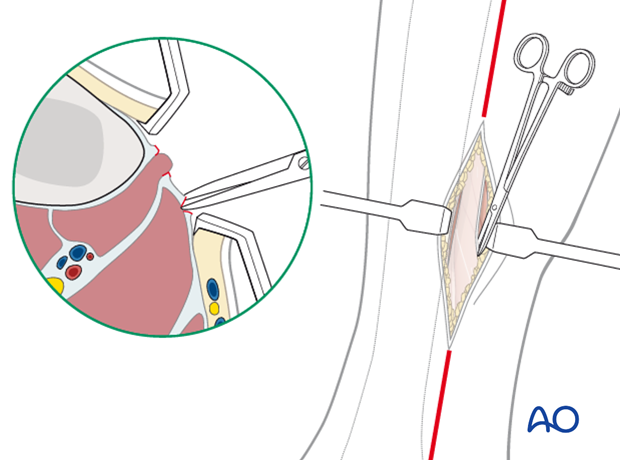

Anterolateral incision

The anterior and lateral compartments are approached through a single longitudinal incision on the outer aspect of the leg, two centimeters anterior to the fibular shaft and long enough to expose the whole length of the compartments. The incision lies approximately over the anterior intermuscular septum that divides the anterior and lateral compartments and allows easy access to both.

A small incision is made in the fascia of the anterior compartment, midway between the septum and the tibial crest. The fascia is opened proximally and distally, respecting any visible superficial nerve.

The lateral compartment fasciotomy is in line with the fibular shaft. Directing the scissors towards the lateral malleolus helps avoid the superficial peroneal nerve as it exits from the fascia in the distal third of the leg near the septum and courses anteriorly. Look for this nerve, which may be branched, and protect it.

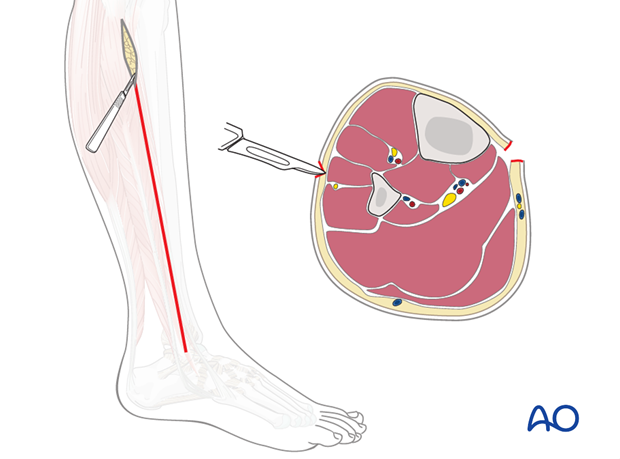

6. Single-incision, parafibular 4-compartment dermato-fasciotomy after Matsen

Introduction

This technique avoids a medial incision, and releases the posterior compartments, as well as anterior and lateral compartments through a single lateral incision. It is essential to ensure that the deep posterior compartment fascia is adequately released. Confirm this by palpating the exposed muscles.

Technique

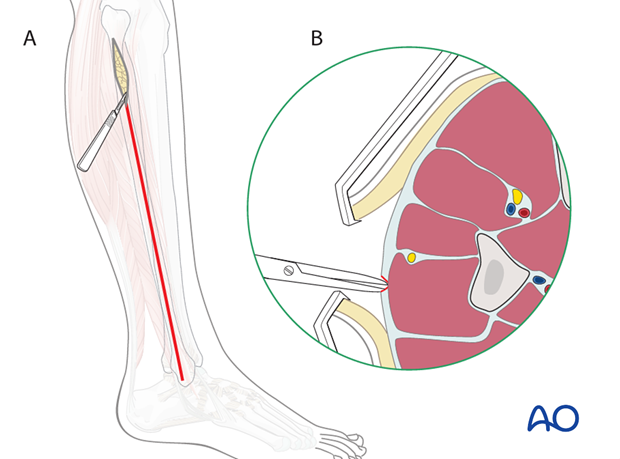

A) An incision is made from the fibular neck to the lateral malleolus.

Note

Protect the common peroneal nerve as it crosses the fibula proximally, and the superficial peroneal nerve distally.

B) The lateral compartment (LC) is opened.

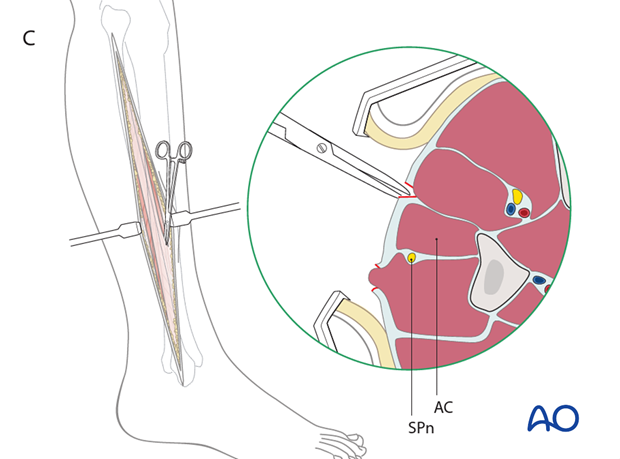

C) Retracting the anterior skin exposes the fascia of the anterior compartment (AC), which is opened, with care being taken to avoid the superficial peroneal nerve (SPn).

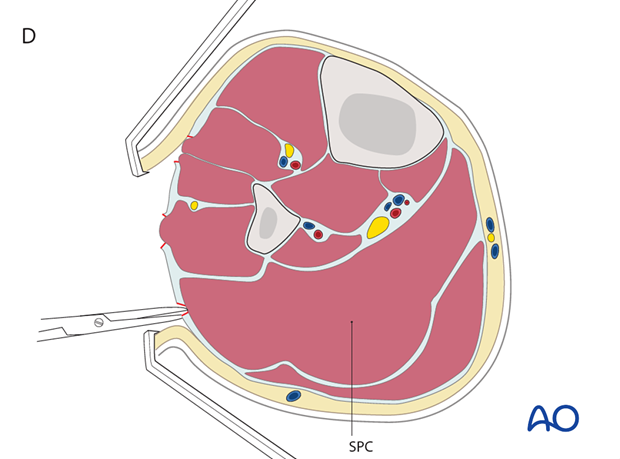

D) The posterior skin is retracted to expose the fascia of the superficial posterior compartment (SPC), which is opened.

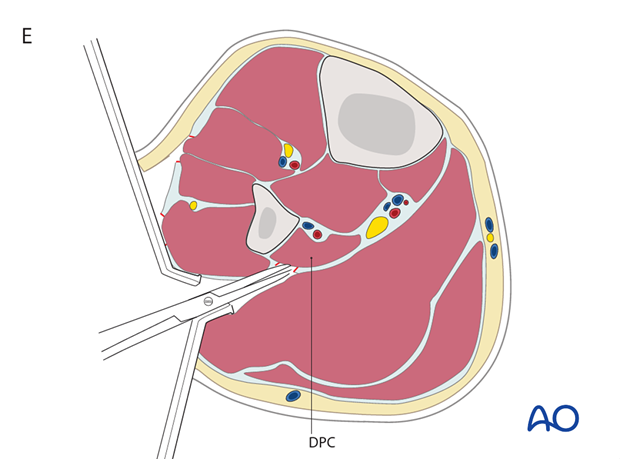

E) The lateral compartment is retracted anteriorly. The soleus is released from the fibular shaft and is retracted posteriorly, exposing the fascia of the deep posterior compartment (DPC), which is opened. Confirm that the deep posterior compartment muscles are released by passively extending and flexing the great toe. This motion changes tension in flexor hallucis longus, which should be felt easily through the open fasciotomy.

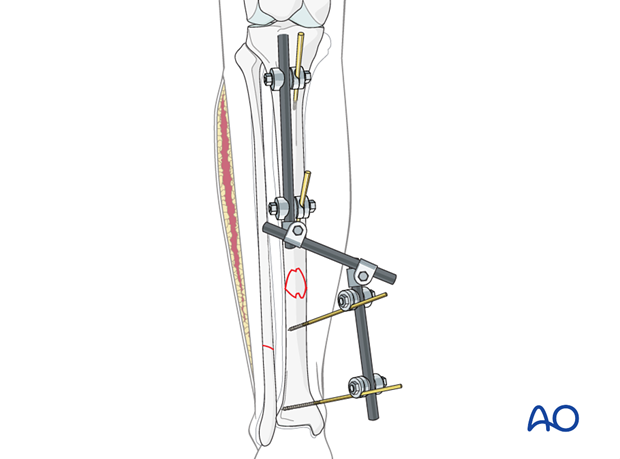

7. Fracture fixation

If fracture stability is important for adequate care of the injured leg, particularly if a compartment syndrome has damaged the local muscles, this can be provided temporarily by external fixation, with minimal additional surgical trauma. Alternatively, internal fixation with an intramedullary nail, or, rarely, a plate, can be done to achieve immediate definitive stabilization, if appropriate. After stabilization, the fasciotomy wounds are left open, as discussed next.

8. Aftercare

Delayed surgical closure

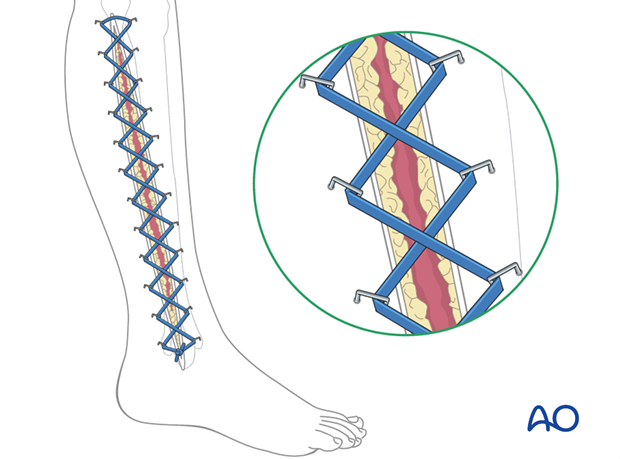

Once any skeletal injury is under control, the fasciotomy wound(s) healthy and the swelling of the soft tissues has sufficiently regressed, consideration must be given to achieving skin coverage.

The simplest and safest technique is to cover the healthy soft-tissue defect with a split skin graft: at a later date, when the limb contours have returned to normal, the grafted area can be excised and secondary skin closure performed without tension.

It is tempting to the surgeon to try early secondary skin suture, rather than skin-graft coverage, once the swelling has subsided. This is only permissible if it can be achieved without any skin tension; it is inadvisable in smokers, who have impaired capacity for soft-tissue healing.

Fasciotomy wound edges tend to retract and become difficult to close. Careful use of elastic retention sutures (elastic vessel loop woven through skin staples) can help counteract skin contraction, and be tightened progressively as swelling resolves. This can help reduce the size of the defect to be covered.

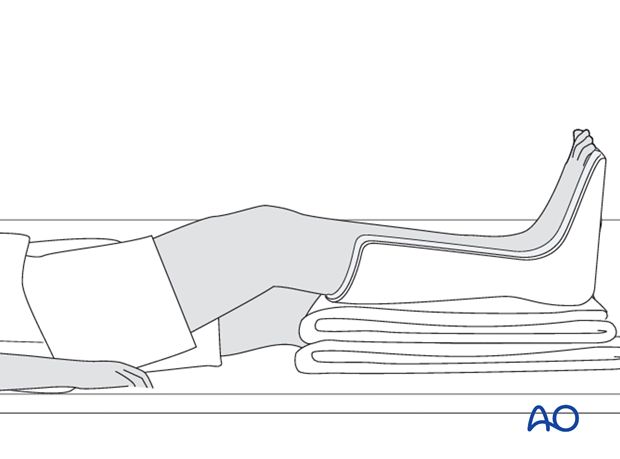

Postoperative splintage

It is important to splint the foot and ankle in a neutral, or dorsiflexed, position to maintain a plantigrade foot, particularly if any muscle damage has occurred and contractures may develop. This can be done with a well-padded plaster back-slab, or with extension of an external fixator to the foot. Maintain toe mobility with passive stretching. Consider K-wire toe fixation, if flexion contractures are developing.