Ligament reconstruction

1. Introduction

Most injuries of the acromioclavicular joint can be treated in a nonoperative fashion. Undisplaced or minimally displaced (Rockwood Types I and II) acromioclavicular injuries are treated with a sling for comfort and gradual return to everyday and recreational activities as pain allows.

Multiple randomized controlled trials do not show any benefit in the majority of cases from routine operative management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations (types III, IV and V). However, operative treatment does play a role in select cases, especially in younger patients, those who work overhead, high performance athletes, and in those with an increasing magnitude of displacement.

Multiple operative procedures have been described for the acute treatment of complete acromioclavicular joint dislocations (ie, hook plate section). This section will describe some of the advantages and disadvantages of a selection of these methods.

2. Coracoacromial ligament transfer

In general, the coracoacromial ligament transfer (Weaver-Dunn transfer) is a useful biological adjunct to an acromioclavicular joint stabilization. However, due to its poor mechanical strength it should not be used in isolation.

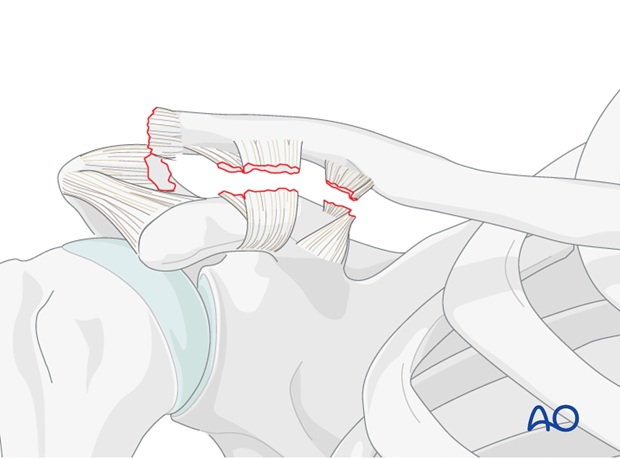

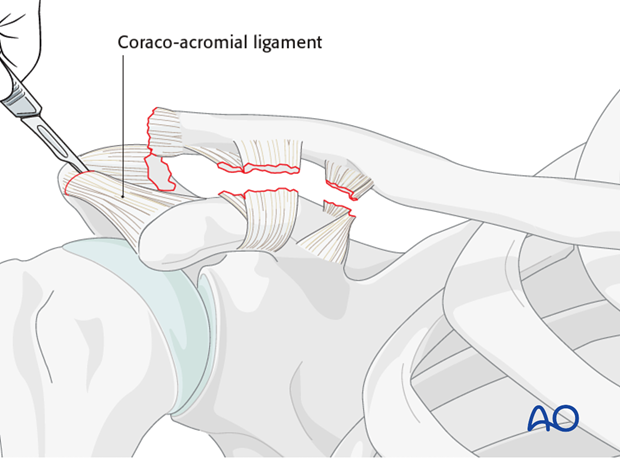

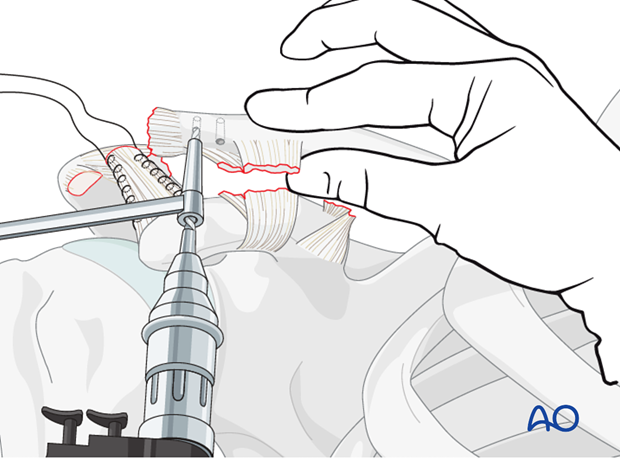

Harvest

The coracoacromial ligament is detached from the acromion by sharp dissection, and mobilized.

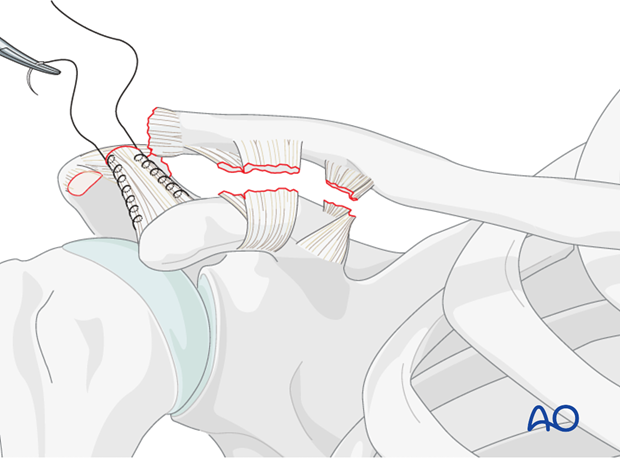

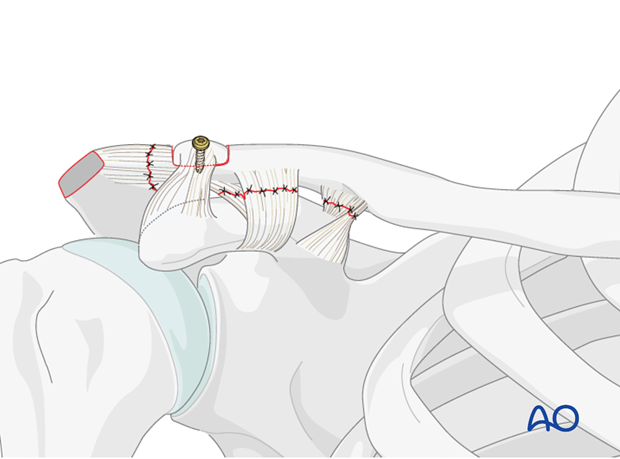

Preparation of ligament

A running locked stitch is placed along the medial and lateral borders of the ligament.

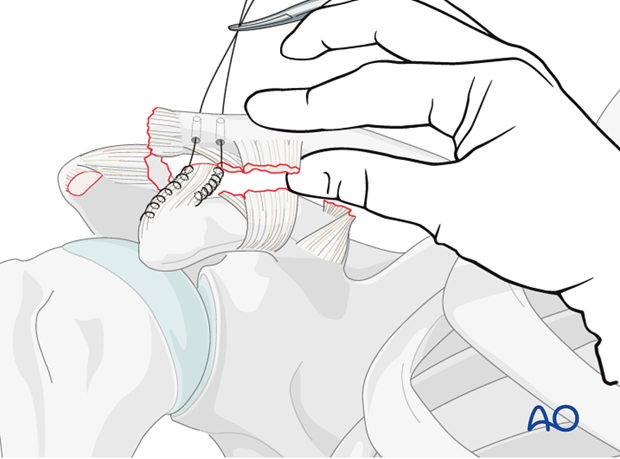

Preparation of recipient site

The anterior inferior surface of the distal clavicle is decorticated to provide an optimal surface for healing. Two drill holes are then placed from an anterior inferior to a posterior superior position.

Attachment of ligament

The two suture limbs are passed through these drill holes so that the free ends of the sutures lie posteriorly and superiorly.

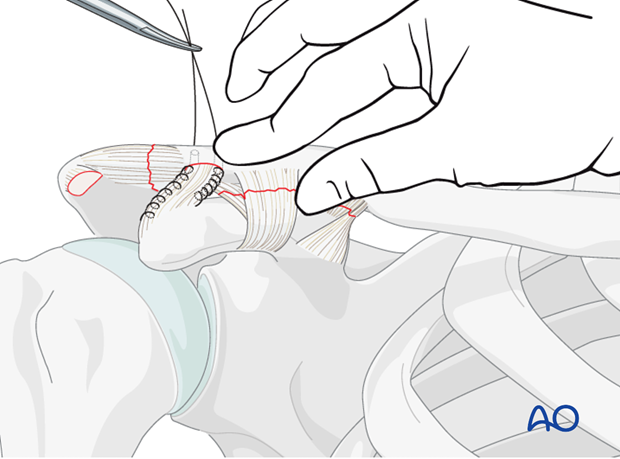

The clavicle is then reduced, the sutures pulled tight, and coracoacromial ligament is approximated to the prepared surface of the distal clavicle. The suture is then tied to secure the transferred ligament in place.

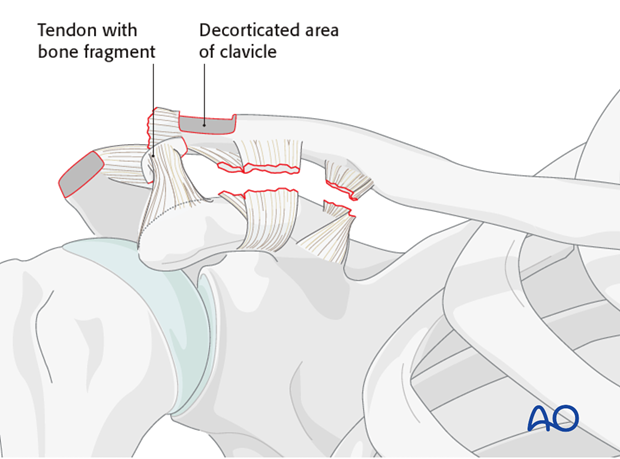

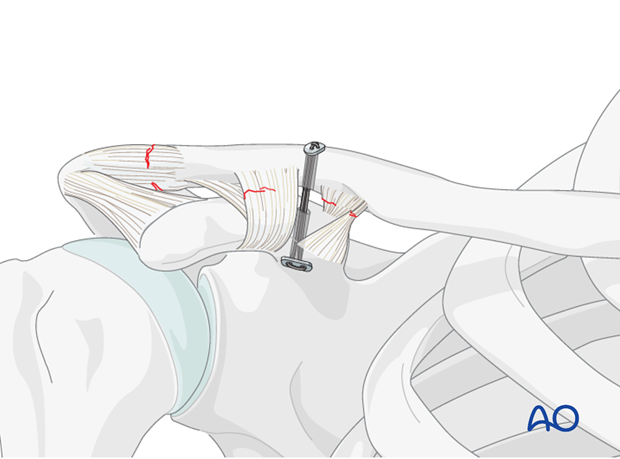

Alternative

Alternatively, the coracoacromial ligament can be transferred with a portion of acromial bone. This is performed by using a small saw to perform an acromial osteotomy of 5-10 mm of anterior bone to detach with the CA ligament.

This bone is then secured to the prepared distal clavicle with a lag screw.

3. Coracoclavicular rope repair

A coracoclavicular rope repair is only indicated when there is a partial rupture of the ligament.

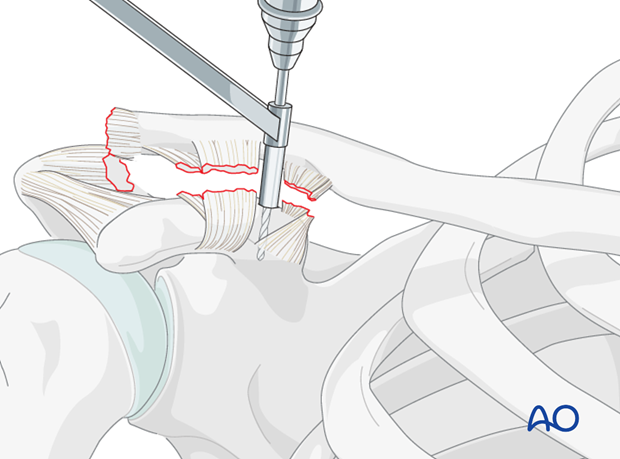

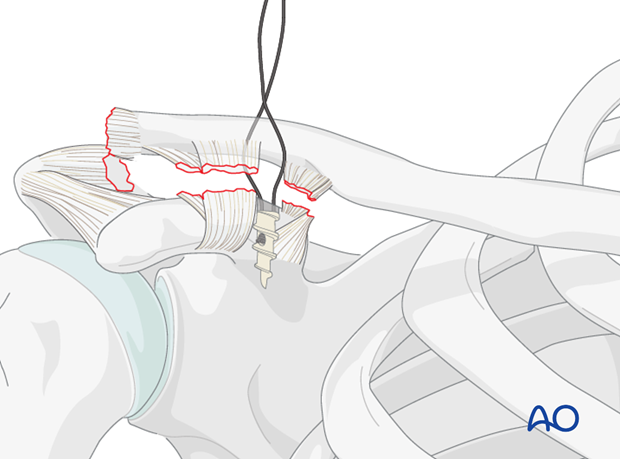

4. Suture anchor

The clavicle is moved slightly dorsally, and a drill guide is used to prepare a monocortical 2.5 mm hole in the coracoid at the level of the ligament insertion.

The suture anchor is inserted, and one fiber is passed dorsal and the other ventral to the clavicle.

The two ends are tight in a knot at the surface of the plate to secure the reduction

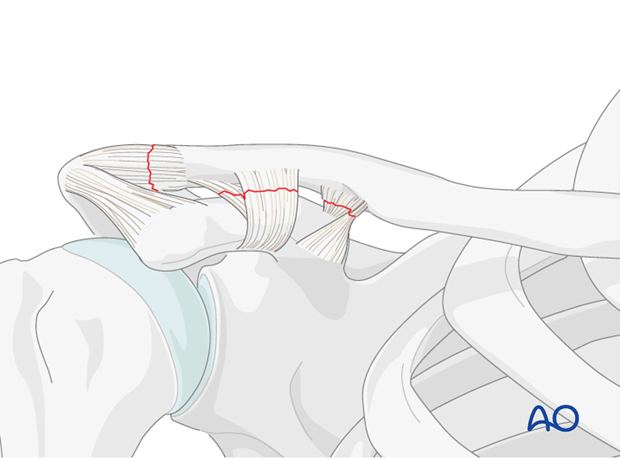

5. Allograft, autograft, tendon reconstruction

This coracoclavicular "sling" technique has the advantage of being a biological method of acromioclavicular repair that allows some physiologic motion between the coracoid and the clavicle. It depends on coracoid integrity to be successful, and can be used either in isolation or combined with other techniques.

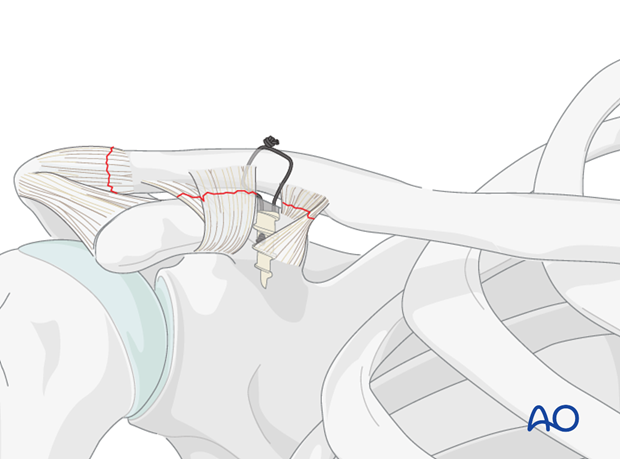

Graft preparation

After exposure of the clavicle and the coracoid the allograft or autograft tendon (typically a hamstring tendon) is prepared. A double loop of tendon is ideal and minimizes risk of failure.

The tendon graft is prepared as one would do for an ACL reconstruction with a running locked non-absorbable large caliber suture.

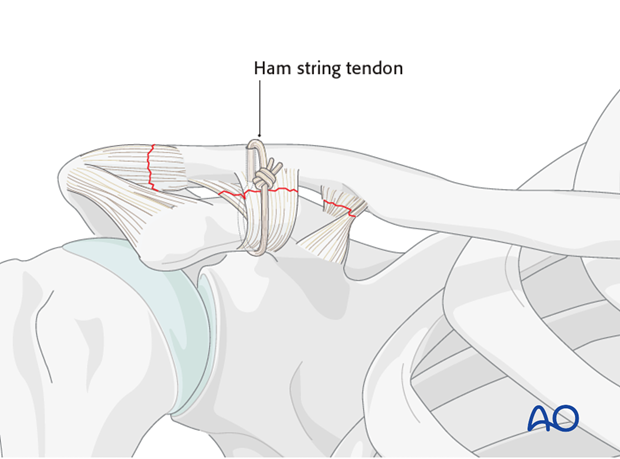

Graft placement

The tendon is passed underneath the coracoid using a tendon or wire passer. Care is taken to stay closely adjacent to the base of the coracoid to minimize the risk of brachial plexus or axillary vessel damage.

The tendon is then passed either around the posterior aspect of the clavicle or through a drill hole in the clavicle immediately superior to the coracoid process.

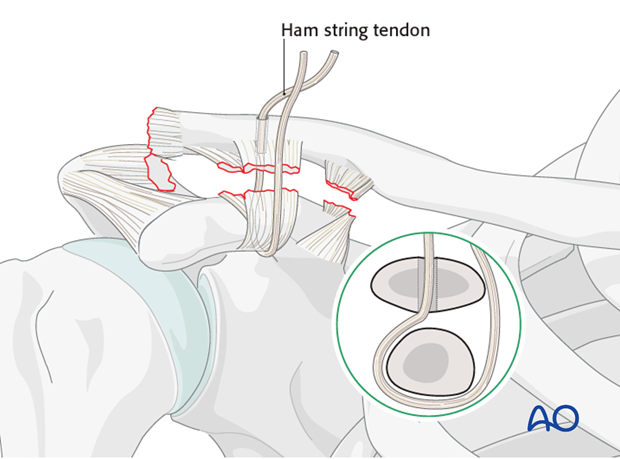

Graft securement

The clavicle is then manually reduced and the hamstring graft is secured in a tight position. Additional strength can be obtained by adding multiple interrupted sutures into the tendon to approximate the two limbs.

Where feasible the prominent knot can be placed anteriorly rather than superiorly to minimize postoperative irritation.

This technique can be used in isolation or in conjunction with other techniques such as plate fixation.