Nailing

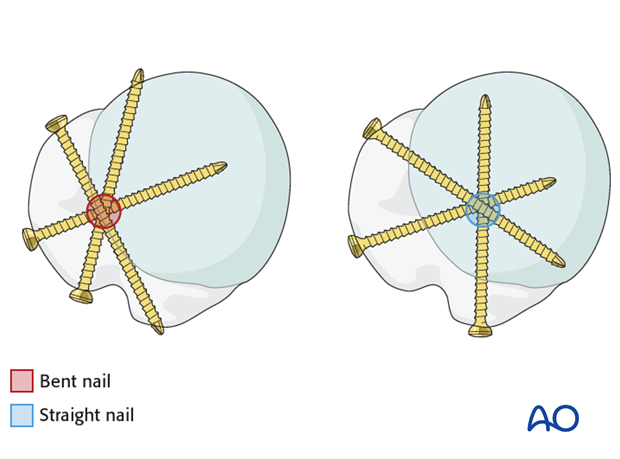

1. Bent vs straight nails

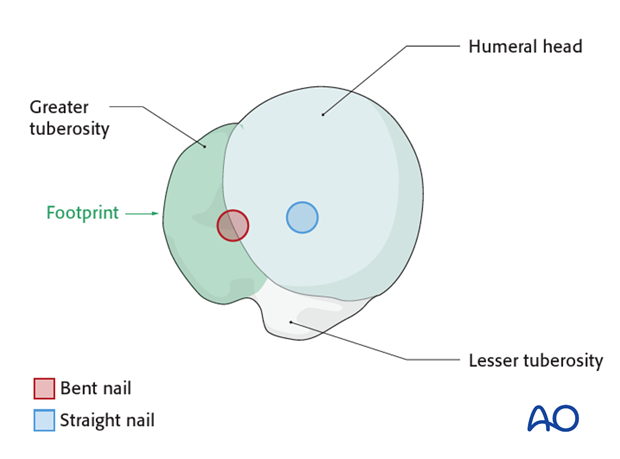

Interference with the rotator cuff footprint

The entry point for a bent nail may go through the bony attachment of the rotator cuff. This bony defect in the footprint cannot be reconstructed later.

The entry point for a straight nail lies under the rotator cuff so the nail is inserted through the rotator cuff. This requires an incision, which should be made in the line of the tendon fibers which can then be closed effectively by a side to side suture.

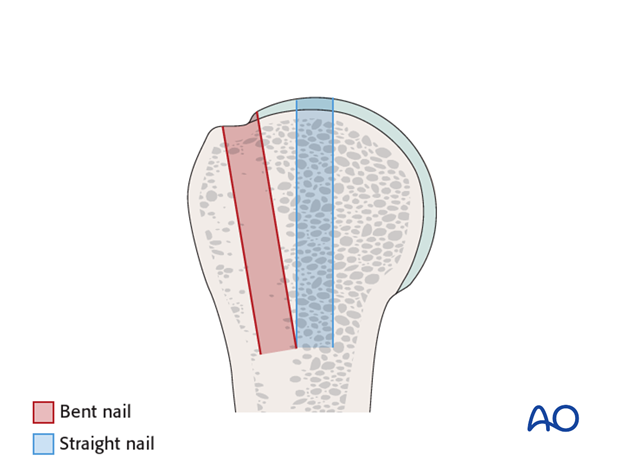

Fixation in osteoporotic bone, fifth anchoring point

Due to the bone density in osteopenic bone straight nails provide a better fixation in the proximal humerus in the region of their entry point. Bent nails run through the greater tuberosity which has a lower bone density compared to the superior humeral head.

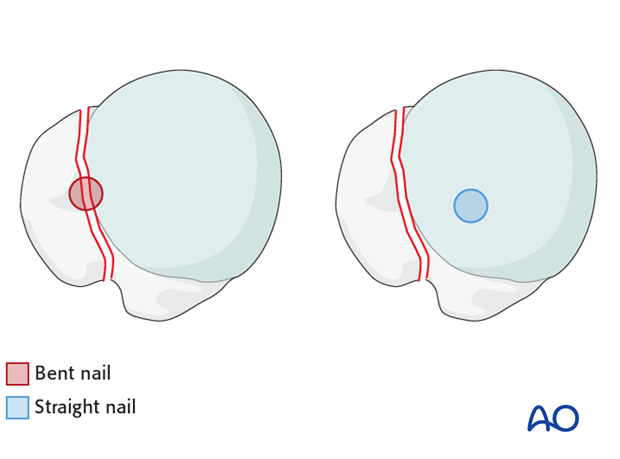

Interference with fracture lines

In proximal humeral fractures which consist of a fracture of the greater tuberosity the trajectory of bent nails often passes through the fracture line between the greater tuberosity and the humeral head whereas straight nails penetrate the humeral head medial to the fracture line.

Fixation pattern of screws

Straight nails run more medial in the axis of the medullary cavity. Therefore, it is possible to perform a direct fixation of the lesser tuberosity through the nail.

2. General considerations

Introduction

Reduction and fixation of the lesser tuberosity helps restore normal function. A nail offers good fixation for the metaphyseal fracture if it must be disimpacted to correct significant angulation. Disimpaction may be unnecessary for a stable impacted fracture.

Sequence of reduction

- Reduce and fix the tuberosity to the humeral head (thereby converting the 3-part fracture into a 2-part situation).

- Reduce the proximal humeral segment to the shaft with the nail and fix it.

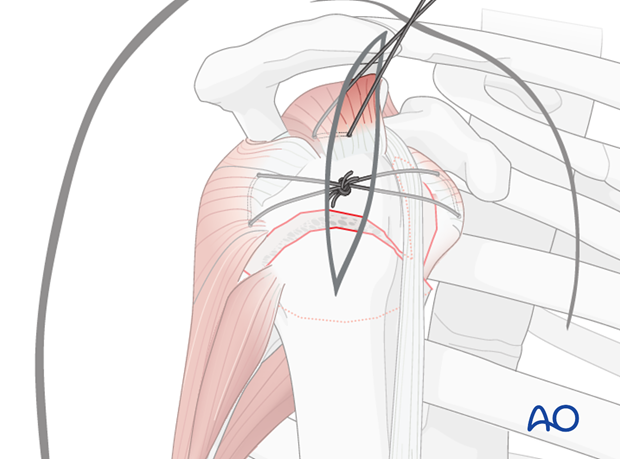

Suture fixation of the lesser tuberosity

Sutures in the subscapularis tendon insertion aid both reduction and fixation of the lesser tuberosity. Once reduced, lesser tuberosity sutures are tied to a similar suture in the infraspinatus tendon for provisional fixation. Ultimately, these sutures contribute significantly to primary stability of the lesser tuberosity.

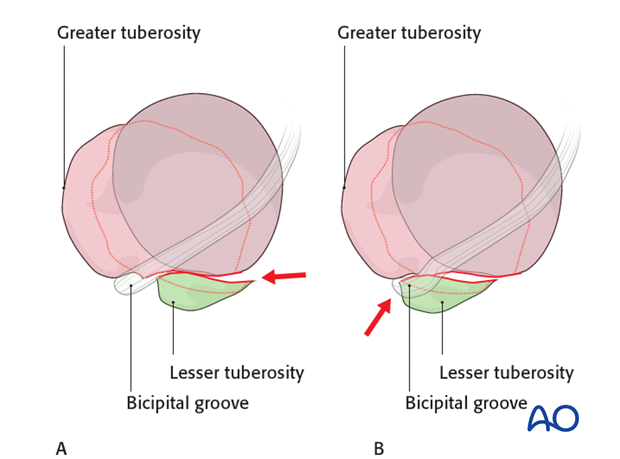

Lesser tuberosity reduction

Proper reduction of the lesser tuberosity is difficult. Its position is hard to visualize with intraoperative image intensification.

Medial displacement of the lesser tuberosity (A) produces an intraarticular anterior step which can compromise internal rotation.

Lateral displacement of the lesser tuberosity (B) obstructs the bicipital groove and may compromise the biceps tendon. If possible, correct reconstruction of the bicipital groove is desirable to allow sliding of the tendon. An alternative would be a tenotomy or tenodesis of the long head of the biceps.

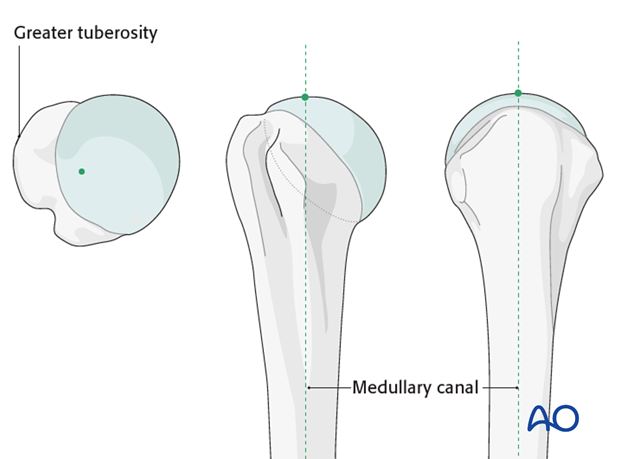

Correct nail entry point

A precise entry point of the humeral nail is crucial. For straight nails, the correct entry point is in line with the axis of the humeral shaft. An incorrect entry site results in malreduction of the metaphyseal fracture.

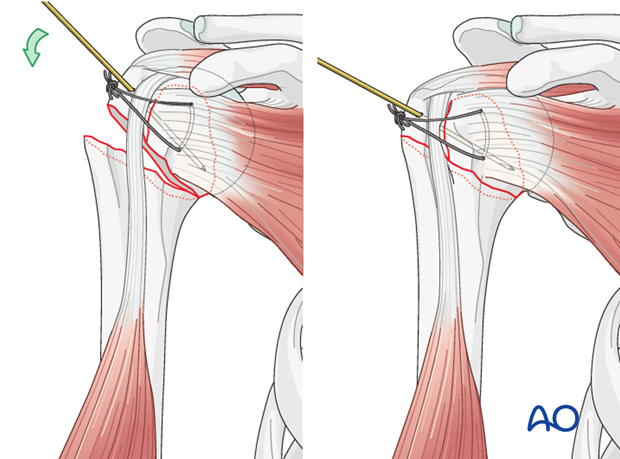

It might be difficult or even not possible to access the correct entry point if the humeral head is displaced severely into a varus position. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to expose the entry point by manipulating the humeral head. K-wire “joy-sticks” (as illustrated) or sutures through the rotator cuff insertions can be used to achieve this.

Reduction of the metaphyseal fracture component

If the entry point has been chosen correctly, insertion of the nail will help reduce the fracture.

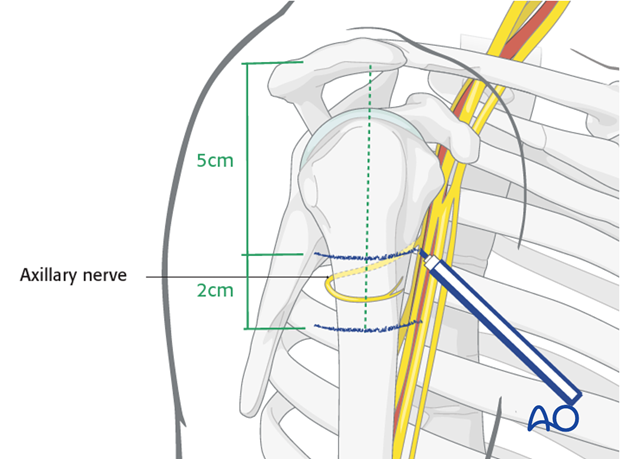

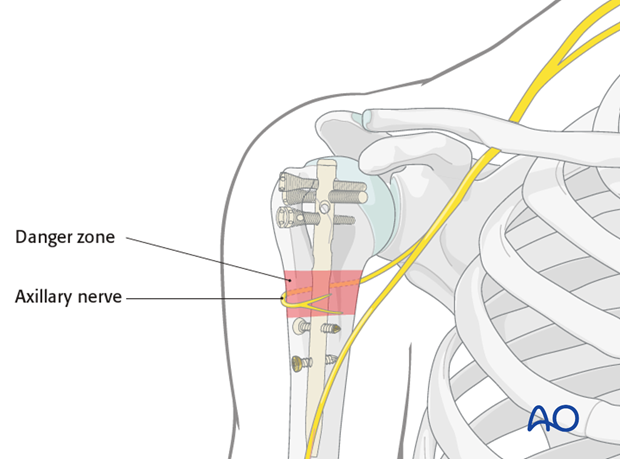

Protection of axillary nerve

The main structure at risk is the axillary nerve. The axillary nerve should be protected by limiting the incision to less than 5 cm distal to the acromial edge, by palpating the nerve, and by avoiding maneuvers that stretch the nerve during reduction and fixation.

In addition, any suspicious screw trajectory should be made to the bone with blunt dissection and checked with finger palpation if necessary.

Remember the course of the nerve when placing the screws depending on the chosen nail and/or position of the nail itself.

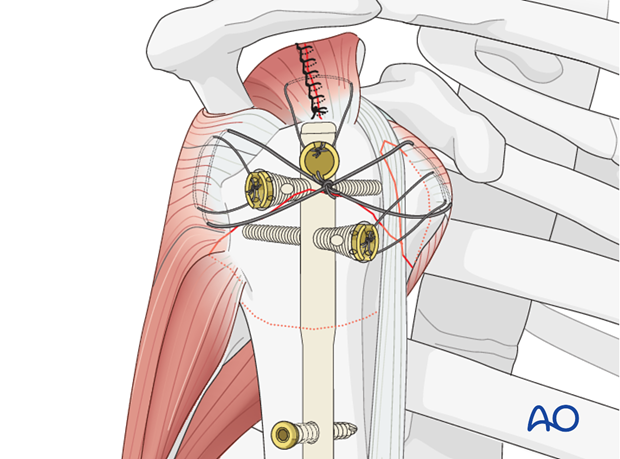

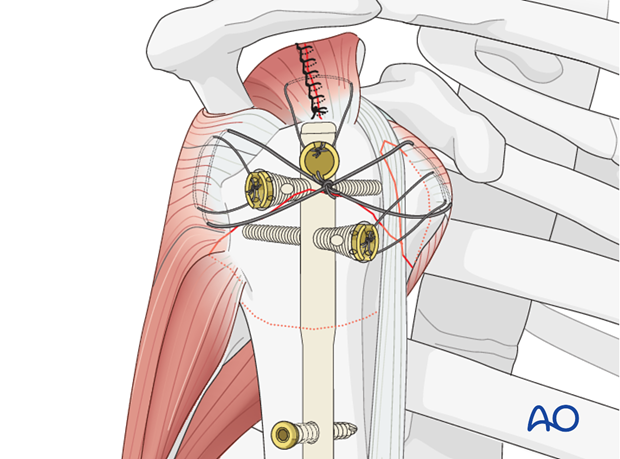

Neutralizing sutures in addition to nail

Sutures placed through the rotator cuff tendons and the bolts increase stability, and should be used as well as the nail and screws, particularly for more comminuted and/or osteoporotic fractures. With osteoporotic bone, the tendon insertion is often stronger than the bone itself, so that sutures placed through the insertional fibers of the tendon may hold better than screws or sutures placed through bone.

These additional sutures are typically the last step of fixation.

This form of fixation was referred to as a “Tension band suture fixation”. We now prefer the term “Neutralizing sutures” because the tension band mechanism cannot be applied consistently to each component of the fracture fixation. An explanation of the limits of the Tension band mechanism/principle can be found here.

Teaching video

AO teaching video: Proximal humerus – 3-part fracture – Reconstruction using the MultiLoc Proximal Humeral Nail

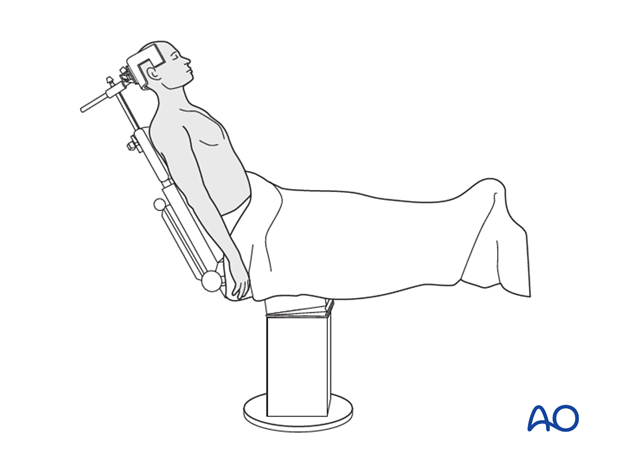

3. Patient preparation and approach

Patient preparation

This procedure is normally performed with the patient in a beach chair position.

Approach

An anterolateral incision is recommended for nailing of proximal humeral fractures. The need for additional access depends upon fracture type. Extension (up to 6 cm) of the anterolateral incision may be needed.

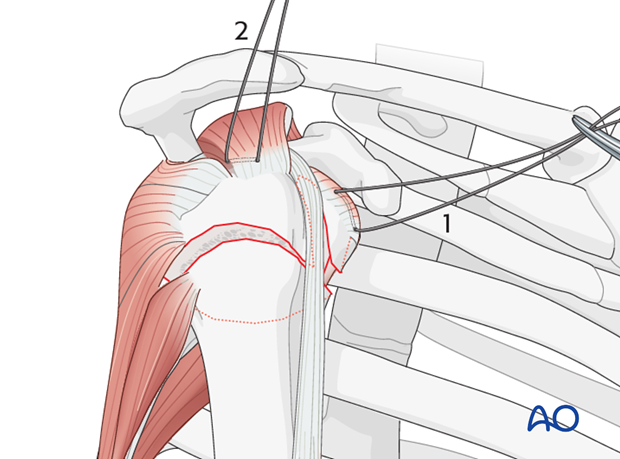

4. Reduction and preliminary fixation of the tuberosities

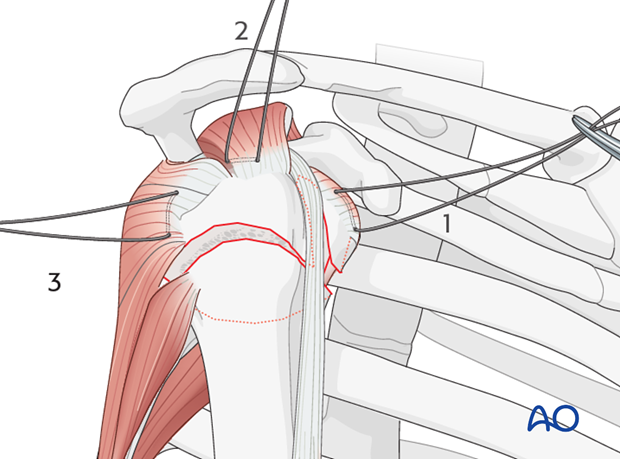

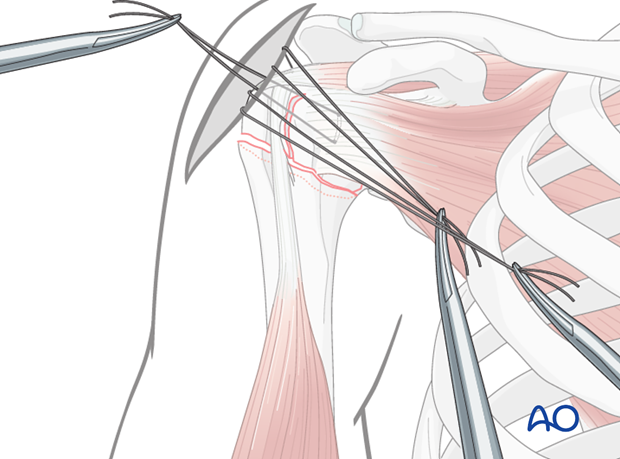

Place rotator cuff sutures

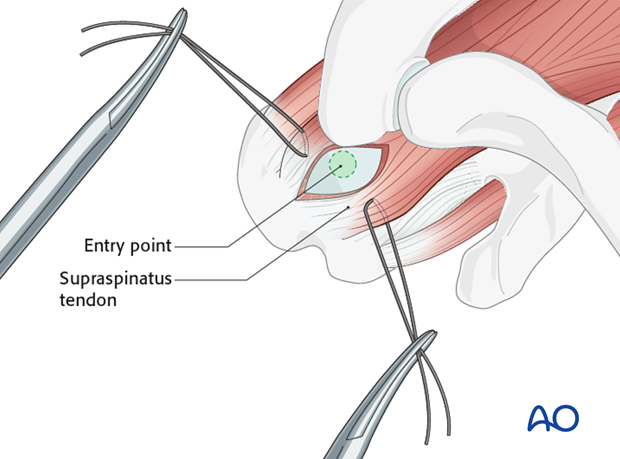

Subscapularis and supraspinatus tendon

Begin by inserting sutures into the subscapularis tendon (1) and the supraspinatus tendon (2). Place these sutures just close to the tendon’s bony insertions. These provide anchors for reduction, and temporary fixation of the greater and lesser tuberosities.

Infraspinatus tendon

Next, place a suture into the infraspinatus tendon insertion (3). This can be demanding, and may be easier with traction on the previously placed sutures, with properly placed retractors, and/or repositioning the arm.

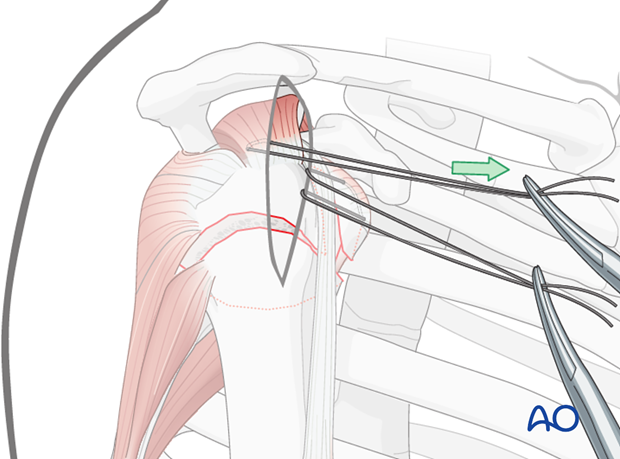

Use of stay sutures

Anterior traction on the supraspinatus tendon helps expose the greater tuberosity and infraspinatus tendon.

Insert a preliminary traction suture into the visible part of the posterior rotator cuff ...

... and pull it anteriorly. This will expose the proper location for a suture in the infraspinatus tendon insertion. Then the initial traction suture is removed.

Pearl - Larger needles: A stout sharp needle facilitates placing a suture through the tendon insertion.

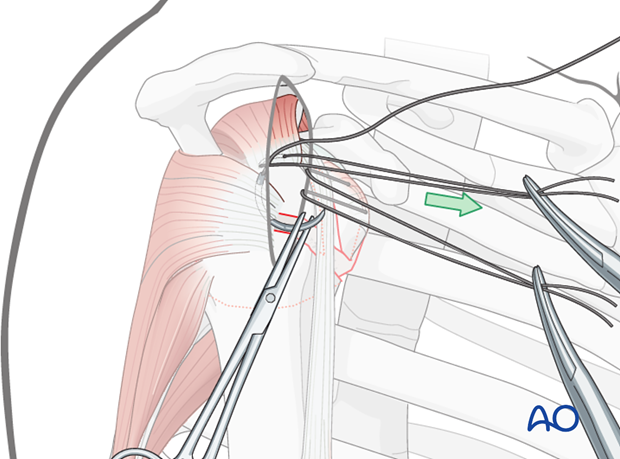

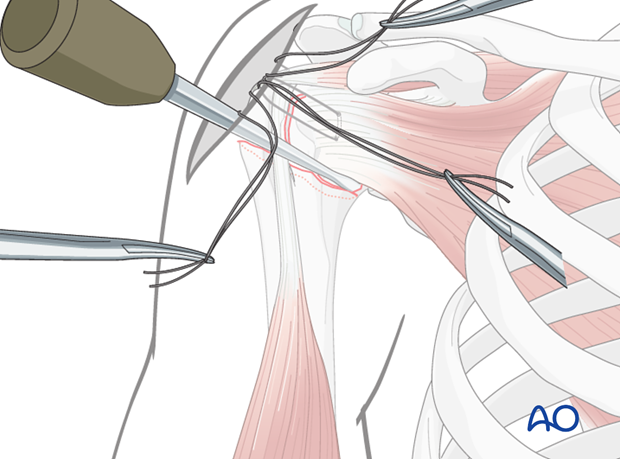

Reduction of the lesser tuberosity

Direct reduction of the lesser tuberosity fragment is performed by pulling the sutures or …

… with instruments (eg, elevator) applied either through the incision (as illustrated) or through a separate stab incision.

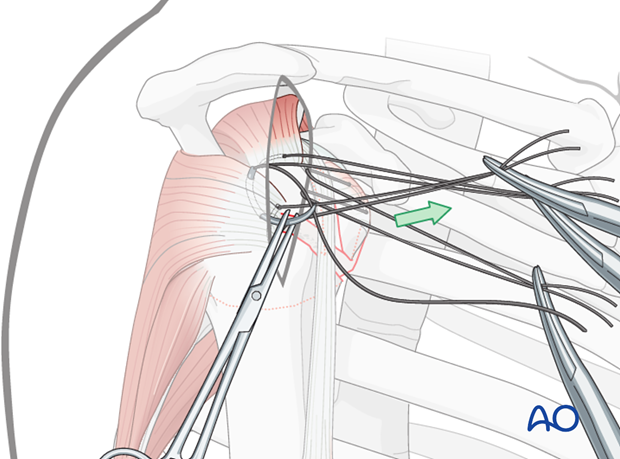

Preliminary suture fixation of the lesser tuberosity

Tighten and tie the transverse sutures in order to preliminarily fix the lesser tuberosity fragment. Thereby, the 3-part fracture is converted into a 2-part situation.

If needed, fix the lesser tuberosity with an additional (cannulated) lag screw.

Preliminary reduction of humeral head

Use of a K-wire

A “joy-stick” technique, as illustrated, may also be helpful to manipulate the humeral head.

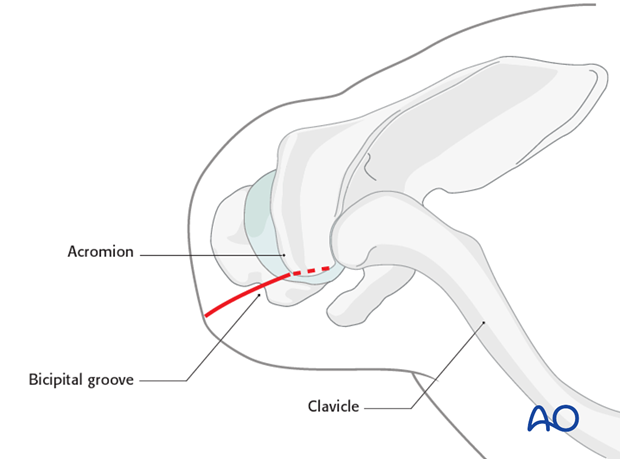

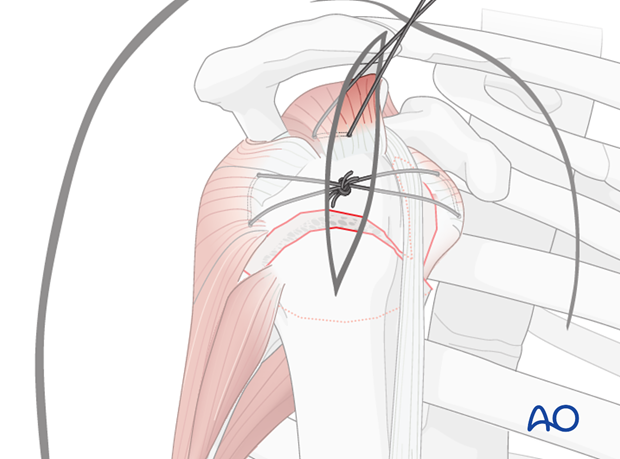

5. Determination of entry point and opening of the canal

Determination and exposure of entry point

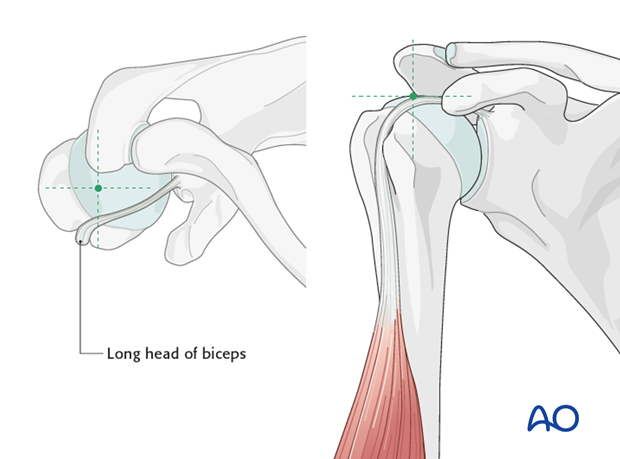

The nail insertion site lies on the axis of the humeral shaft. It is located intraarticularly posterior to the tendon of the long head of the biceps within the cartilage. It is typically near the highest point of the humeral head. It is slightly anterior to the center of the greater tuberosity. A supraspinatus split is necessary.

Incise the supraspinatus tendon for approximately 3 cm over the foreseen entrance point posterior to the long head of the biceps. Retract the edges of the supraspinatus tendon with the help of stay sutures.

Insert a K-wire through the correct entry point and confirm proper placement by image intensification.

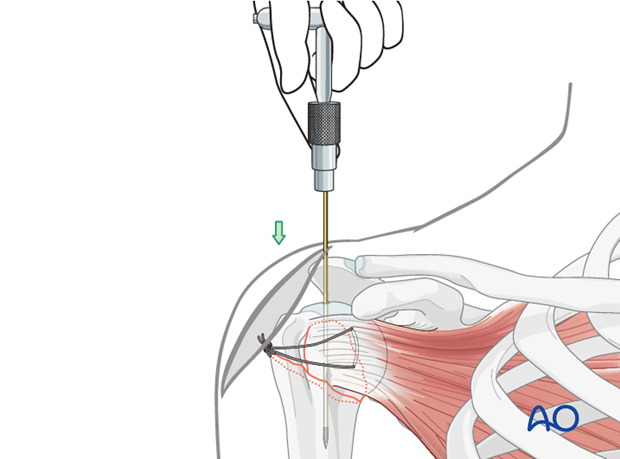

Open the humerus

A cannulated drill bit is recommended for opening the proximal humerus. This drill bit should be inserted over the previously placed guide wire. It should be advanced into the proximal medullary canal.

Alternatively, an awl may be used to open the humerus.

Take care not to displace the tuberosity fracture during passage of awl or drill.

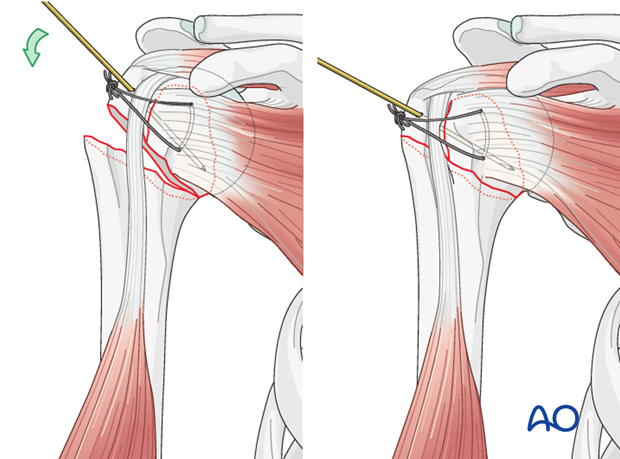

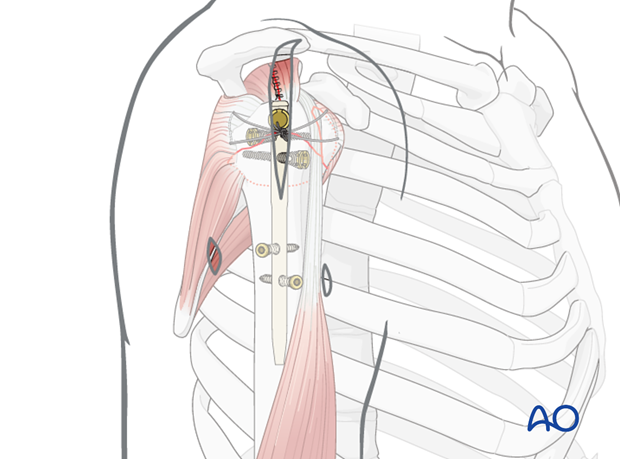

6. Nail insertion

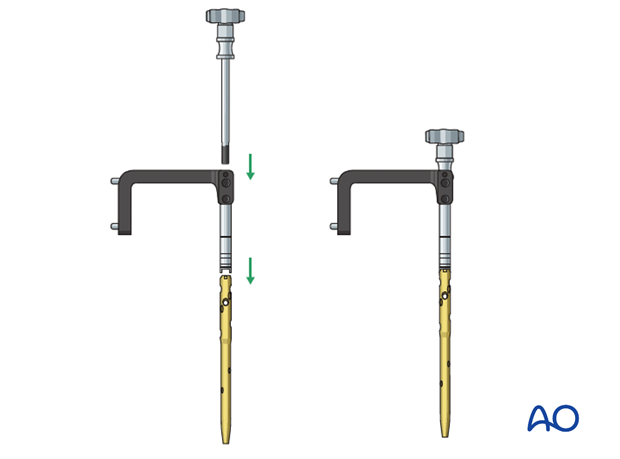

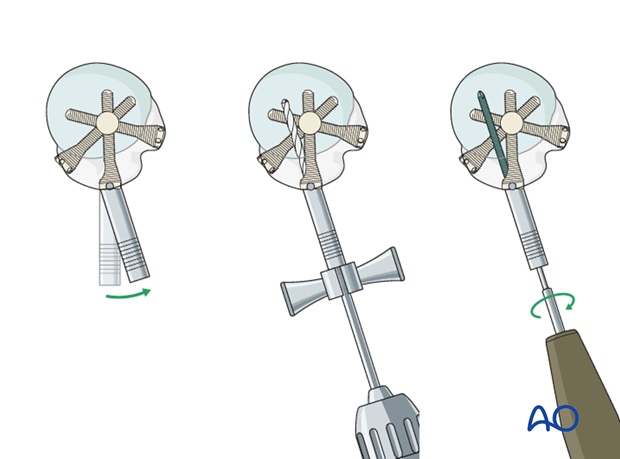

Mount nail on insertion handle

The humeral nail is mounted on an insertion handle. The nail must be rotated correctly relative to the insertion handle.

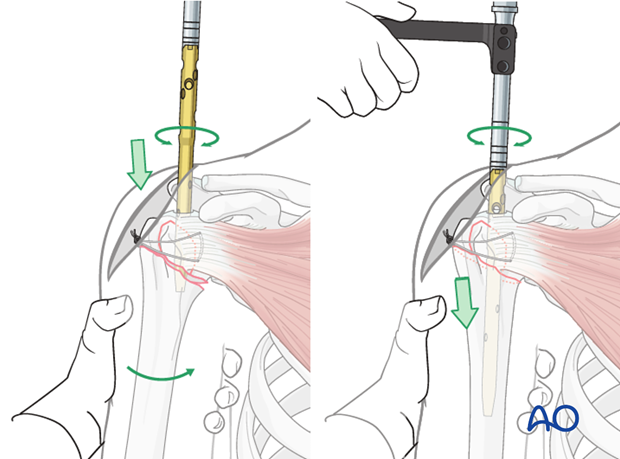

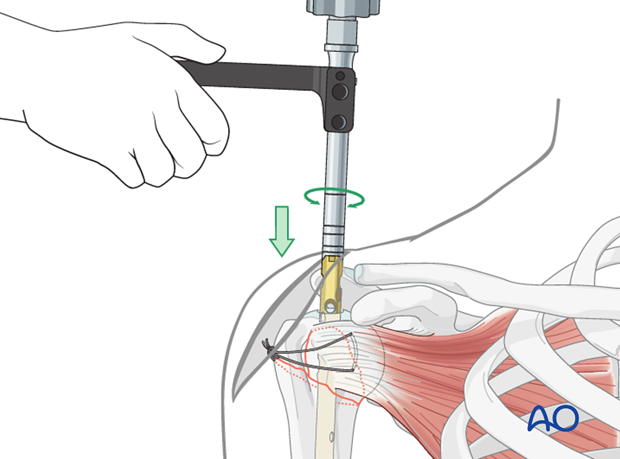

Insert nail

Insert the nail with slightly rotating movements down to the metaphyseal fracture line. Pass the fracture zone under image intensification and make sure that the nail enters the distal fragment properly.

Make sure the proximal end of the nail is placed beneath the bony surface of the humeral head.

No protrusion of the nail may be tolerated. Confirm with appropriately oriented C-arm images that the nail is below the bone.

Be careful not to redisplace tuberosity fractures when inserting proximal locking components.

A K-wire placed through an aiming device may help to adjust the appropriate insertion depth.

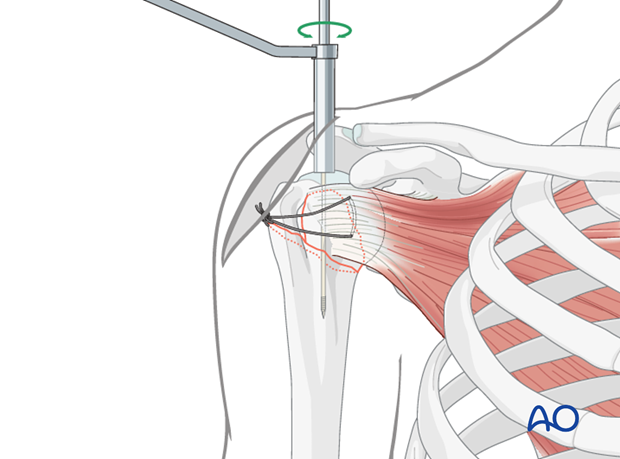

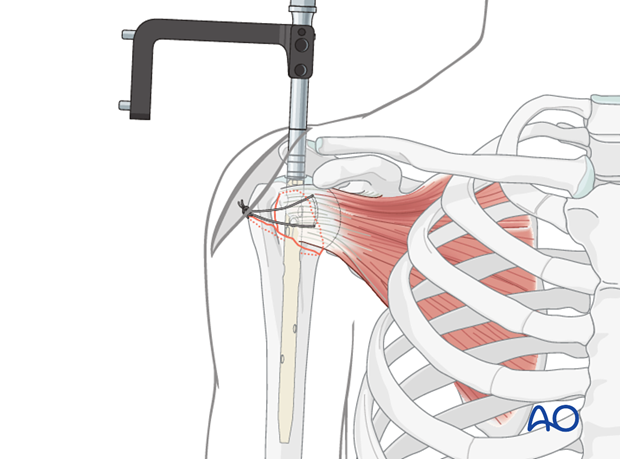

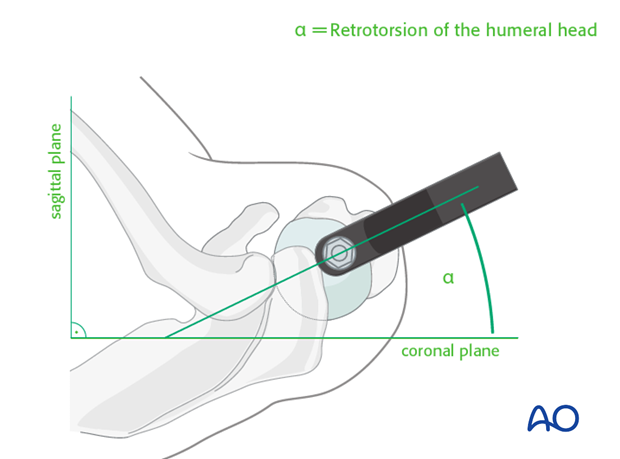

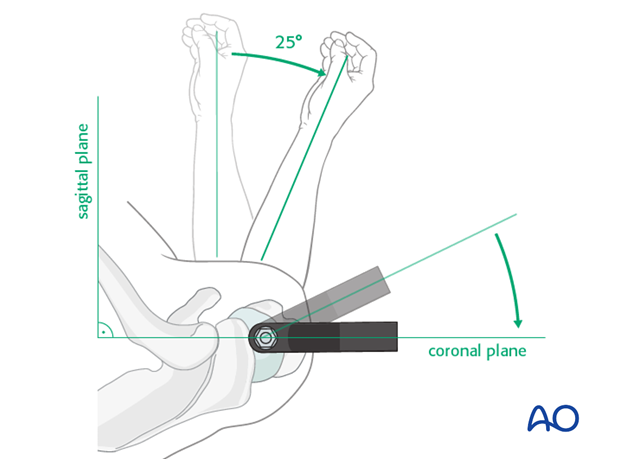

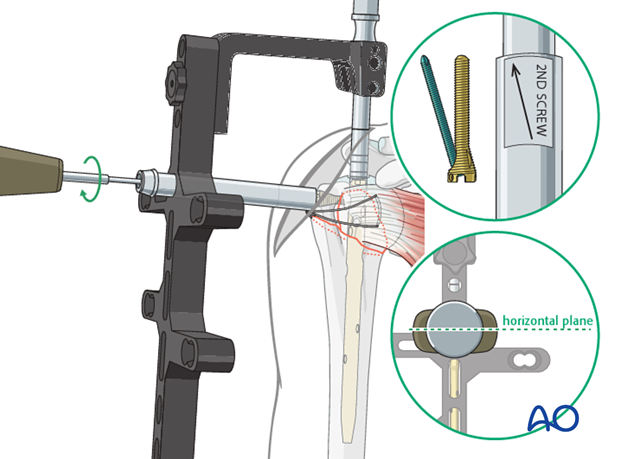

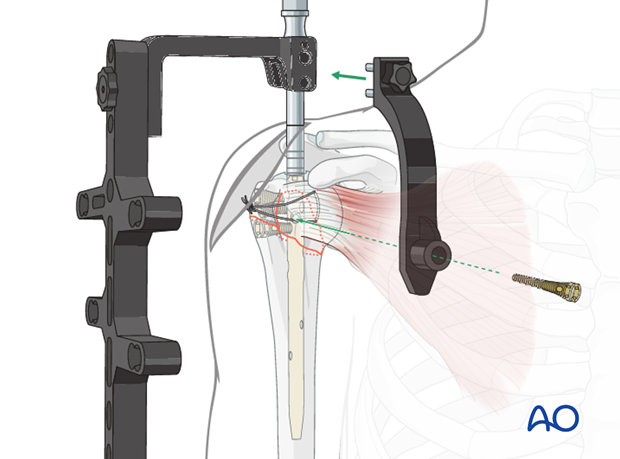

Retrotorsion of the nail

In order to lock the nail in the correct trajectory, mount the aiming arm and swivel it approximately 25° anteriorly in order to follow the retroverted axis of the humeral head. (Due to the physiological retrotorsion of the humeral head, the axis of the humeral head is directed approximately 25° posteriorly to the condylar plane of the distal humerus.)

This is also important if a direct screw fixation of the lesser tuberosity is intended in order to prevent any injury of the biceps tendon.

To obtain a true AP view of the proximal humerus, the forearm has to be rotated approximately 25° externally relative to the sagittal plane.

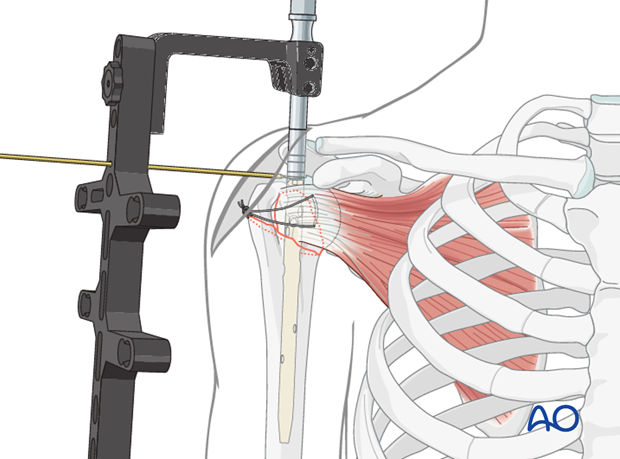

7. Proximal nail fixation

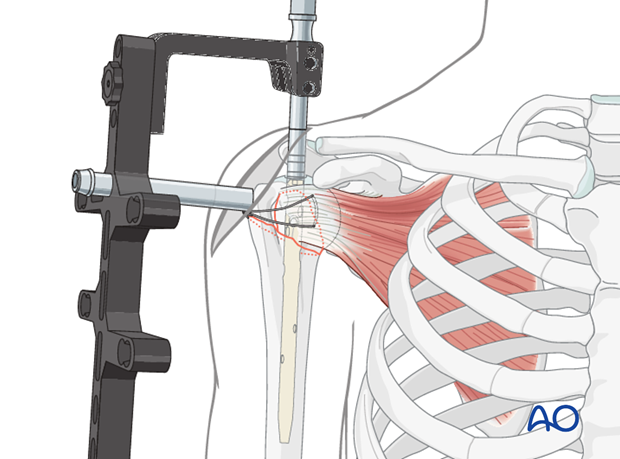

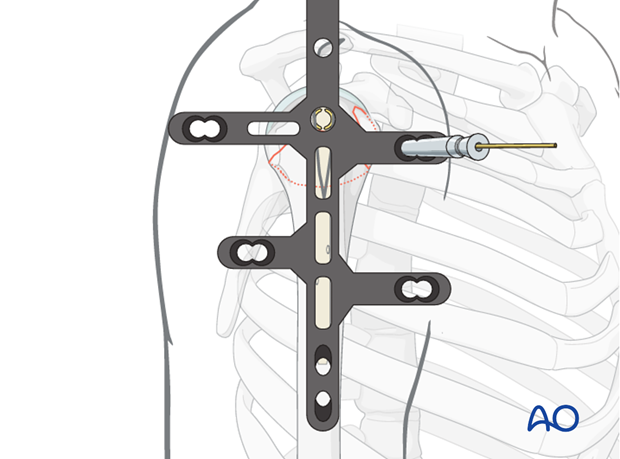

Insert trocar

The trocar for the planned screw fixation is placed through the aiming device, if necessary through a separate skin incision. Perform blunt dissection down to the bone so that the trocar may be placed without interposition of soft tissue.

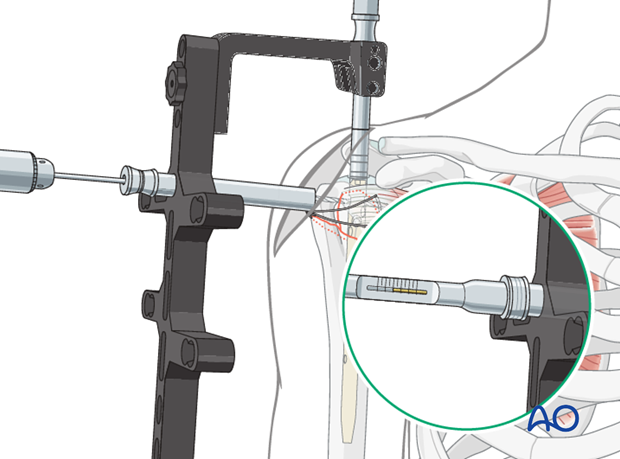

Predrilling

Check once more the correct retrotorsion.

Drill with the calibrated drill bit carefully just to the level of the subchondral bone. The final position of the drill bit can be checked with the image intensifier. The screw length can be determined from the measurements of the drill bit.

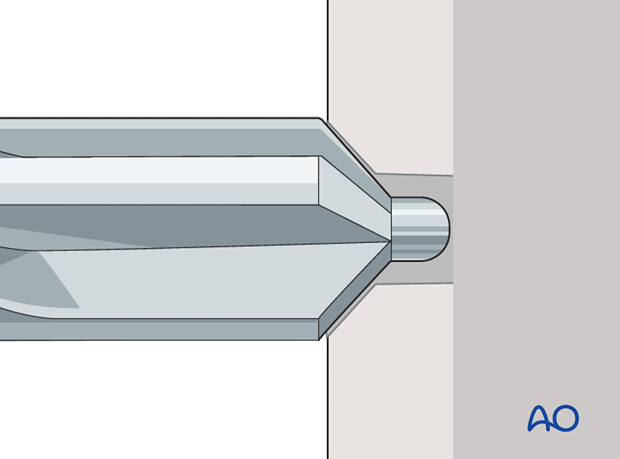

Widen the screw hole in the lateral cortex

If necessary, a conical drill bit may be used to countersink the lateral cortex.

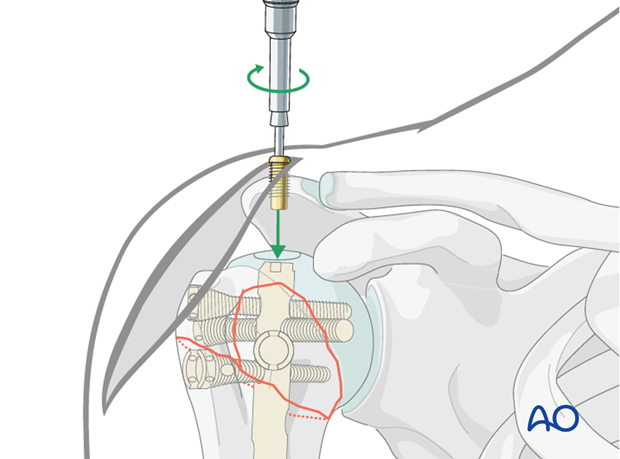

Insert screw

Attach the screw to the screw driver and insert the screw.

In some systems, as the one shown in this illustration, a screw-in-screw fixation is possible (see below). If so and if also intended, the plane of the handle of the screw driver should be horizontal and the arrow should point posteriorly once the final position of the screw is reached.

Pearl: Using an additional trocar, K-wires can help to achieve more stability temporarily.

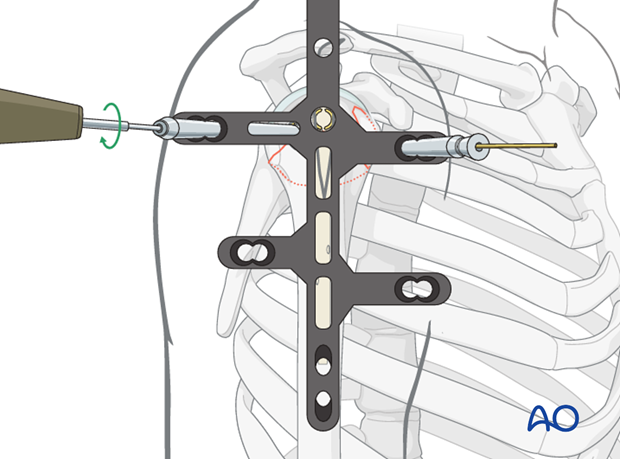

Insert further screws

Insert further screws using the aiming device according to the fracture pattern.

Fix the lesser tuberosity

If necessary, fix the lesser tuberosity with an additional, anterior screw. Doing so, mount an anterior aiming arm to the aiming device and insert the screw as described above.

Screw-in-screw insertion

If necessary, use the screw-in-screw fixation for further stability.

Attach the centering sleeve to the already inserted screw, turn it anteriorly until it locks.

Insert the drill sleeve and predrill to the subchondral bone.

After length measurement insert the screw with the screw driver and torque limiter.

Calcar screw insertion

If necessary (such as varus fractures), insert a calcar screw through the aiming device in the way as described for the other screws.

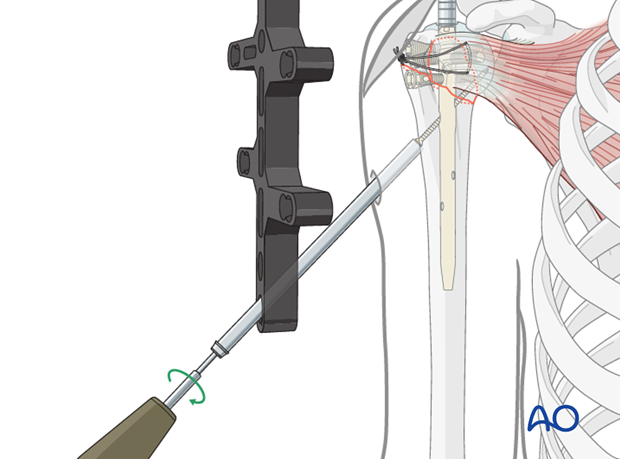

8. Distal nail fixation

Drill and determine length of locking screw

For distal locking, insert the trocar with the drill sleeve through one of the distal holes in the aiming device. Drill through both humeral cortices until the bit just breaks through the medial cortex and read the depth from the drill bit. Alternatively, a depth gauge can be used.

Insert a locking screw through the trocar. A second screw is recommended, especially in osteoporotic bone.

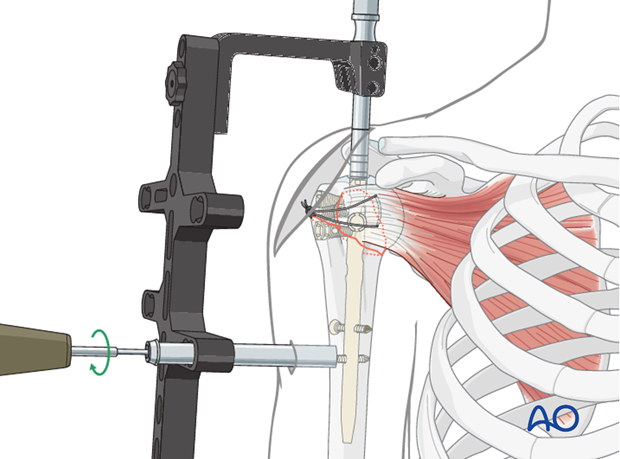

9. Finalizing the nailing

Insert end cap

The end cap prevents tissue from plugging the inner thread of the nail.

End caps are available in different sizes and can, if necessary, be used to extend the nail. The top of the end cap must not protrude above the surface of the bone.

Repair rotator cuff

Suture the supraspinatus split.

Supplementary rotator cuff tendon sutures

Rotator cuff neutralizing sutures are placed through the dedicated holes of the bolts.

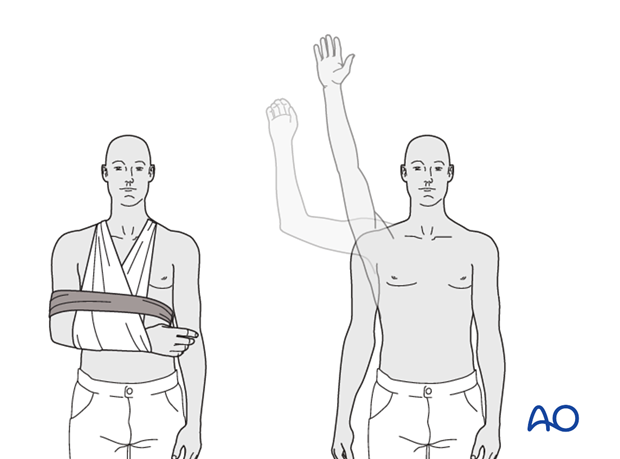

10. Overview of rehabilitation

The shoulder is perhaps the most challenging joint to rehabilitate both postoperatively and after conservative treatment. Early passive motion according to pain tolerance can usually be started after the first postoperative day - even following major reconstruction or prosthetic replacement. The program of rehabilitation has to be adjusted to the ability and expectations of the patient and the quality and stability of the repair. Poor purchase of screws in osteoporotic bone, concern about soft-tissue healing (eg tendons or ligaments) or other special conditions (eg percutaneous cannulated screw fixation without tension-absorbing sutures) may enforce delay in beginning passive motion, often performed by a physiotherapist.

The full exercise program progresses to protected active and then self-assisted exercises. The stretching and strengthening phases follow. The ultimate goal is to regain strength and full function.

Postoperative physiotherapy must be carefully supervised. Some surgeons choose to manage their patient’s rehabilitation without a separate therapist, but still recognize the importance of carefully instructing and monitoring their patient’s recovery.

Activities of daily living can generally be resumed while avoiding certain stresses on the shoulder. Mild pain and some restriction of movement should not interfere with this. The more severe the initial displacement of a fracture, and the older the patient, the greater will be the likelihood of some residual loss of motion.

Progress of physiotherapy and callus formation should be monitored regularly. If weakness is greater than expected or fails to improve, the possibility of a nerve injury or a rotator cuff tear must be considered.

With regard to loss of motion, closed manipulation of the joint under anesthesia, may be indicated, once healing is sufficiently advanced. However, the danger of fixation loosening, or of a new fracture, especially in elderly patients, should be kept in mind. Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions or even open release and manipulation may be considered under certain circumstances, especially in younger individuals.

Progressive exercises

Mechanical support should be provided until the patient is sufficiently comfortable to begin shoulder use, and/or the fracture is sufficiently consolidated that displacement is unlikely.

Once these goals have been achieved, rehabilitative exercises can begin to restore range of motion, strength, and function.

The three phases of nonoperative treatment are thus:

- Immobilization

- Passive/assisted range of motion

- Progressive resistance exercises

Immobilization should be maintained as short as possible and as long as necessary. Usually, immobilization is recommended for 2-3 weeks, followed by gentle range of motion exercises. Resistance exercises can generally be started at 6 weeks. Isometric exercises may begin earlier, depending upon the injury and its repair. If greater or lesser tuberosity fractures have been repaired, it is important not to stress the rotator cuff muscles until the tendon insertions are securely healed.

Special considerations

Glenohumeral dislocation: Use of a sling or sling-and-swath device, at least intermittently, is more comfortable for patients who have had an associated glenohumeral dislocation. Particularly during sleep, this may help avoid a redislocation.

Weight bearing: Neither weight bearing nor heavy lifting are recommended for the injured limb until healing is secure.

Implant removal: Implant removal is generally not necessary unless loosening or impingement occurs. Implant removal can be combined with a shoulder arthrolysis, if necessary.

Shoulder rehabilitation protocol

Generally, shoulder rehabilitation protocols can be divided into three phases. Gentle range of motion can often begin early without stressing fixation or soft-tissue repair. Gentle assisted motion can frequently begin within a few weeks, the exact time and restriction depends on the injury and the patient. Resistance exercises to build strength and endurance should be delayed until bone and soft-tissue healing is secure. The schedule may need to be adjusted for each patient.

Phase 1 (approximately first 3 weeks)

- Immobilization and/or support for 2-3 weeks

- Pendulum exercises

- Gently assisted motion

- Avoid external rotation for first 6 weeks

Phase 2 (approximately weeks 3-9)

If there is clinical evidence of healing and fragments move as a unit, and no displacement is visible on the x-ray, then:

- Active-assisted forward flexion and abduction

- Gentle functional use week 3-6 (no abduction against resistance)

- Gradually reduce assistance during motion from week 6 on

Phase 3 (approximately after week 9)

- Add isotonic, concentric, and eccentric strengthening exercises

- If there is bone healing but joint stiffness, then add passive stretching by physiotherapist